The Near-Death Experience and Tibetan De/Ogs " Lee W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Structure and Function of Near-Death Experiences: an Algorithmic Reincarnation Hypothesis

Journal of Near-Death Studies ph079-jnds-362310 November 17, 2001 11:40 Style file version March 18, 1999 The Structure and Function of Near-Death Experiences: An Algorithmic Reincarnation Hypothesis Todd Murphy San Francisco, CA ABSTRACT: Hypothesizes that a near-death experience (NDE) is the subjective experience of having the state of consciousness in which a person experiences the last moment of his or her life being turned, in stages, into the state of consciousness experienced as the “point of no return.” The life review this, as is interpreted as a review of the states of consciousness experienced during our lives. Our responses to reviewing our own behaviors while in specific states reinforces and classifies them into those to repeat in future lives and those to avoid. We examine a modification of the traditional doctrine of reincarnation that takes into account biological and cultural evolution. This allows an understanding of how the attributes of NDEs could have undergone selection even though all opportunities for mating have already passed at the time of death. KEY WORDS: near-death experience; reincarnation; Buddhism; rebirth. Seventy percent of near-death experiencers (NDErs) return from their experiences believing in reincarnation (Wells, 1993). Often, they tell of being counseled about the life they lived, and given help in planning their following lives. Not only NDErs, but also a large group of past life regression hypnotherapists (for example, Whitton, 1986) and several major religious traditions accept the doctrine of reincarnation. Ian Stevenson has also uncovered several types of evidence relating Todd Murphy is an associate researcher with the Behavioral Neurosciences Program at Laurentian University under the direction of Michael A. -

The Facts on Near-Death Experiences

The Facts on Near-Death Experiences By Dr. John Ankerberg and Dr. John Weldon Published by ATRI Publishing Copyright 2011, Updated 2021 ISBN 9781937136055 License Notes This eBook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This eBook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author. Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture verses are taken from the New American Standard Bible, © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. Verses marked NIV are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by the International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. The “NIV” and “New International Version” trademarks are registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by International Bible Society. Verses marked KJV are taken from the King James Version of the Bible. The verse marked Berkeley is taken from the Modern Language Bible: The New Berkeley Version, copyright © 1991 by Hendrickson Publishing, Inc., Peabody, MA. Contents Title page A Personal Message Chapter 1: Why are NDEs a more vital subject than people think? Chapter 2: Do NDEs decrease or increase suicidal tendencies? Chapter 3: What about abortion and NDEs? Chapter 4: What are some theological consequences of the NDE and its popular interpretation? Chapter 5: What about the NDEs that teach reincarnation? Chapter 6: What are the day-to-day consequences of many NDEs? Chapter 7: What are some problems of near-death -

Near-Death Experiences and the Theory of the Extraneuronal Hyperspace

Near-Death Experiences and the Theory of the Extraneuronal Hyperspace Linz Audain, J.D., Ph.D., M.D. George Washington University The Mandate Corporation, Washington, DC ABSTRACT: It is possible and desirable to supplement the traditional neu rological and metaphysical explanatory models of the near-death experience (NDE) with yet a third type of explanatory model that links the neurological and the metaphysical. I set forth the rudiments of this model, the Theory of the Extraneuronal Hyperspace, with six propositions. I then use this theory to explain three of the pressing issues within NDE scholarship: the veridicality, precognition and "fear-death experience" phenomena. Many scholars who write about near-death experiences (NDEs) are of the opinion that explanatory models of the NDE can be classified into one of two types (Blackmore, 1993; Moody, 1975). One type of explana tory model is the metaphysical or supernatural one. In that model, the events that occur within the NDE, such as the presence of a tunnel, are real events that occur beyond the confines of time and space. In a sec ond type of explanatory model, the traditional model, the events that occur within the NDE are not at all real. Those events are merely the product of neurobiochemical activity that can be explained within the confines of current neurological and psychological theory, for example, as hallucination. In this article, I supplement this dichotomous view of explanatory models of the NDE by proposing yet a third type of explanatory model: the Theory of the Extraneuronal Hyperspace. This theory represents a Linz Audain, J.D., Ph.D., M.D., is a Resident in Internal Medicine at George Washington University, and Chief Executive Officer of The Mandate Corporation. -

Spiritual Aftereffects of Incongruous Near-Death Experiences: a Heuristic Approach

SPIRITUAL AFTEREFFECTS OF INCONGRUOUS NEAR-DEATH EXPERIENCES: A HEURISTIC APPROACH A dissertation presented to the Faculty of Saybrook University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Sciences by Robert Waxman San Francisco, California November 2012 UMI Number: 3552161 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3552161 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 UMI Number: All rights reserved © 2012 by Robert Waxman Approval of the Dissertation SPIRITUAL AFTEREFFECTS OF INCONGRUOUS NEAR-DEATH EXPERIENCES: A HEURISTIC APPROACH This dissertation by Robert Waxman has been approved by the committee members below, who recommend it be accepted by the faculty of Saybrook University in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Sciences Dissertation Committee: ______________________________ ________________________ Robert McAndrews, Ph.D., Chair Date ______________________________ ________________________ Stanley Krippner, Ph.D. Date ______________________________ ________________________ Willson Williams, Ph.D. Date ii Abstract SPIRITUAL AFTEREFFECTS OF INCONGRUOUS NEAR-DEATH EXPERIENCES: A HEURISTIC APPROACH Robert Waxman Saybrook University Many individuals have experienced a transformation of their spirituality after a near-death experience (NDE). -

Lear-Death Studiesi

JNDAE7 18(3) 139-210 (2000) ISSN 0891-4494 Journal of I lear-Death Studies ) s Editor's Foreword " Bruce Greyson, M.D. Near-Death Studies and Modern Physics e Craig R. Lundahl, Ph.D. and Arvin S. Gibson The Induction of After-Death Communications Utilizing Eye-Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing: A New Discovery * Allan L. Botkin, Psy.D. Volume 18, Number 3, Spring 2000 Editor Bruce Greyson, M.D., University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA Consulting Editors James E. Alcock, Ph.D., C. Psych., York University, Toronto, Ont. Boyce Batey, Academy of Religion and Psychical Research, Bloomfield, CT Carl B. Becker, Ph.D., Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan Diane K. Corcoran, R.N., Ph.D., 3G International,Reston, VA Kevin J. Drab, M.A., C.A.C., C.E.A.P., The Horsham Clinic, Ambler, PA Glen O. Gabbard, M.D., The MenningerFoundation, Topeka, KS Stanislav Grof, M.D., Mill Valley, CA Michael Grosso, Ph.D., New Jersey City University, Jersey City, NJ Barbara Harris Whitfield, R.T.T., Ms.T., Whitfield Associates, Atlanta, GA Bruce J. Horacek, Ph.D., University of Nebraska, Omaha, NE Pascal Kaplan, Ph.D., Searchlight Publications,Walnut Creek, CA Raymond A. Moody, Jr., Ph.D., M.D., Anniston, AL Russell Noyes, Jr., M.D., University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA Canon Michael Perry, Durham Cathedral, Durham, England Kenneth Ring, Ph.D., University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT William G. Roll, Ph.D., PsychologicalServices Institute, Atlanta, GA Steven Rosen, Ph.D., City University of New York, Staten Island, NY W. Stephen Sabom, S.T.D., Decatur, GA Stuart W. -

Life After Death Spaces Still Available in Spring 2013 Courses!

Volume 2, Issue 4 Conscious, holistic approaches to end of life Near Death, Our Hearts Rest Easy Life after Four Deaths Death in the Virtual World: How Facebook and other Internet Sites Allow the Dead to Live on Aya Despacho: A Prayer Package for the Dead Soul Passage Midwifery Life after Death Spaces still available in Spring 2013 courses! 2 | WINTER 2013 | | NATURAL TRANSITIONS MAGAZINE | 3 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Natural Transitions Magazine | Volume 2, Issue 4 DEPARTMENTS FEATURES 6 EDITORIAL Near Death, Our Hearts Rest Easy 4 What to Expect When You Die by Patsea Cobb by Karen van Vuuren 8 Life after Four Deaths by Christopher Sassano COMMUNITY FORUM 5 Chinese Orphanages 13 Newtown Shooting Characteristics of a Near-Death Experience by International Association for Near-Death Studies 14 CULTURAL CONNECTIONS Caring for the Near-Death Experiencer: 20 Aya Despacho: A Prayer Package Advice to Caregivers for the Dead by Kitty Edwards by International Association for Near-Death Studies 16 A TIME TO DIE Death in the Virtual World: How Facebook and other Internet Sites 30 An Activist’s T-Shirt Shroud Allow the Dead to Live On by Lorelei Esser by Jaweed Kaleem 24 IN SPIRIT Healing the Past before We Die Again by Christine Hart, MD 32 The Power of Merit by Andrew Holecek 26 Soul Passage Midwifery by Patricia L’Dara MEDIA 33 34 Book Review: I Knew Their Hearts by Lee Webster Near Death Wisdom: Response to Tragedy by Eben Alexander, MD LAST WORDS 35 Venus by Julie Clement The Little Prince by Antoine Saint-Exupery Cover photo: Spirit Departing by Patsea Cobb acrylic 2 | WINTER 2013 | | NATURAL TRANSITIONS MAGAZINE | 3 editorial What to Expect When You Die by Karen van Vuuren Our fear of death is foremost a fear of the unknown. -

THE AFTERLIFE AS a PATHWAY to a MORE PURPOSEFUL LIFE by CARLTON J. BULLER a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the R

THE AFTERLIFE AS A PATHWAY TO A MORE PURPOSEFUL LIFE by CARLTON J. BULLER A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF METAPHYSICAL SCIENCE July 14, 2015 On behalf of the Department of Graduate Studies of the University of Metaphysics this submission has been accepted by the Thesis Committee. _________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor _________________________________________ Dean _________________________________________ President Acknowledgements From the tender age of five, until I was eleven years old, while suffering multiple types of abuse at the hands of perpetrating adults, my spirit somehow knew that it had to separate from my body in order to protect me from the physical and emotional pain. And I began traveling out of my body in my dreams and while awake. The abuse had forced me through the doorway of astral projection and into the reality of other parallel existences. As I grew up and matured, my natural curiosity about these and other related topics moved me to further investigate possibilities beyond our physical reality. That ultimately led to multiple paranormal experiences. These culminated with a dream where I traveled out of my body and witnessed an event in real time as it happened. This ultimately convinced me that there is indeed life beyond our physical manifestation, and for that I am extremely grateful. Am I grateful to my perpetrators for the abuse they precipitated upon me? That is an extremely difficult case to make. But everything is connected. There are no accidents. And there is no longer any doubt in my mind that everything that has unfolded in my life happened the way it did in order to make me who I am. -

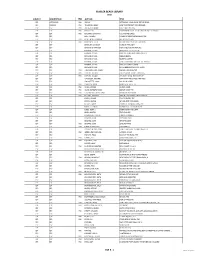

Flagler Beach Library Esp P. 1

FLAGLER BEACH LIBRARY 2015 SUBJECT DESCRIPTION TYPE AUTHOR TITLE ESP ASTROLOGY PBK ZODIAC ASTROLOGY: YOUR GUIDE TO THE STARS ESP DREAMS PBK THURSTON, MARK HOW TO INTERPRET YOUR DREAMS ESP ESP PBK ALTEA, ROSEMARY EAGLE AND THE ROSE ESP ESP PBK BADER, LOIS COMPANION GUIDE TO THE ONLY PLANET OF CHOICE ESP ESP PBK BALDWIN, CHRISTINA CALLING THE CIRCLE ESP ESP BALL, PAMELA POWER OF CREATIVE THINKING. THE ESP ESP PBK BOYER & NISSENBAUM SALEM POSSESSED ESP ESP PBK BRADY & ST. LIFER DISCOVERING YOUR SOUL MISSION ESP ESP BRINKLEY, DANNION SAVED BY THE LIGHT ESP ESP BROWNE & HARRISON PAST LIVES, FUTURE HEALING ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA ADVENTURES OF A PSYCHIC ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA GOD, CREATION AND TOOLS FOR LIFE ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA PHENOMENON ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SECRET SOCIETIES ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SECRETS AND MYSTERIES OF THE WORLD ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SPIRITUAL CONNECTIONS ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SYLVIA BROWN'S BOOK OF ANGEL ESP ESP PBK CALLEMAN, CARL JOHAN MAYAN CALENDAR, THE ESP ESP PBK CAPUTO, THERESA THERE'S MORE TO LIFE THAN THIS ESP ESP PBK CAPUTO, THERESA YOU CAN'T MAKE THIS STUFF UP ESP ESP CAVENDISH, RICHARD MAN MYTH AND MAGIC PART TWO ESP ESP CHOQUETTE, SONIA ASK YOUR GUIDES ESP ESP PBK CIANCIOSI, JOHN MEDITATIVE PATH, THE ESP ESP PBK CLARK, JEROME UNEXPLAINED ESP ESP PBK CLOW, BARBARA HAND MAYAN CODE, THE ESP ESP PBK COOPER, MILTON WILLIAM BEHOLD A PALE HORSE ESP ESP PBK DELONG, DOUGLAS ANCIENT TEACHINGS FOR BEGINNERS ESP ESP DIXON, JEANNE CALL TO GLORY, THE ESP ESP DIXON, JEANNE MY LIFE AND PROPHECIES ESP ESP DOSSEY, LARRY POWER OF PREMONITIONS, THE ESP ESP DRUSE, ELEANOR JOURNALS OF ELEANOR DRUSE ESP ESP EADIE, BETTY J. -

Bibliography on Dying and the Afterlife

BOOKS ON DEATH, DYING, & BEFORE/BEYOND (Compiled by Timothy Conway, Ph.D. --Revised 1999, 2006) *** Scholarly, scientific, popular, parapsychological, and cross-cultural/anthropological works: Almeder, Robert, Death & Personal Survival: The Evidence for Life After Death , NY: Rowman & Littlefield, 1992 (by a renowned Fulbright scholar/philosopher of biomedical ethics; “On Reincarnation: A Reply to Hales, Philosophia (Dec. 2000), vol. 28 nos.1-4; “Recent Responses to Survival Research,” J. of Scientific Exploration , Spring 1997, vol. 10, no. 4, 495ff.) Anabiosis: The Journal for Near-Death Studies (1981- ) and newsletter Vital Signs (1979- ) published by the International Assoc. for Near-Death Studies (website: iands.org), P.O. Box 502, East Windsor Hill, CT 06028-0502 (Kenneth Ring, Ed.). Aries, Philippe, The Hour of Our Death (H. Weaver, Trans.), NY: Knopf, 1981; Images of Man and Death (J. Lloyd, Trans.), Cambridge, MA: Harvard U. Press, 1985 (by a pioneering researcher on the phenomenon of death). Atwater, P.M.H., Beyond the Light: What Isn’t Being Said about Near-Death Experience , NY: Carol, 1994 (by a survivor). Bailey, Lee W., & Jenny Yates, The Near Death Experience: A Reader , Routledge, 1996 (good compilation of leading authors). Berman, Phillip, The Journey Home: What Near-Death Experiences and Mysticism Teach Us About the Gift of Life , Pocket, 1998. Bache, Christopher, Lifecycles: Reincarnation and the Web of Life , NY: Paragon, 1991 (excellent, eloquent philosophical work). Bowman, Carol, Return From Heaven: Beloved Relatives Reincarnated Within Your Family , HarperCollins 2001; Children’s Past Lives: How Past Life Memories Affect Your Child , Bantam, 1998 (good popular works, especially for parents; with novel cases) Brinkley, Dannion (with Paul Perry), Saved By the Light , Villard, 1994; At Peace In the Light , HarperCollins, 1995 (popular-level works by a NDE survivor who became highly psychic as a result of the “zapping” experience). -

The Influence of Some Ancient Philosophical and Religious Traditions on the Soteriology of Early Christianity

The Influence of some Ancient Philosophical and Religious Traditions on the Soteriology of Early Christianity by Jan Albert Gibson Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology in the subject Systematic theology atthe University of South Africa. Supervisor: Prof. Erasmus van Niekerk August 2002 Declaration I the undersigned hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is 1ny own original work and has not previously in its entirety or in part been submitted at any university for a degree. - . Signature ~ llHl~ll~l~l~ll~ll~ll 0001807587 THE INFLUENCE OF SOME ANCIENT RELIGIOUS AND PHILOSOPHICAL TRADITIONS ON THE SOTERIOLOGY OF EARLY CHRISTIANITY Summary When reading the Bible in an independent way, i.e., not through the lenses of any official Church dogma, one is amazed by the many voices that come through to us. Add to this variety the literary finds from Nag Hammadi, as well as the Dead Sea Scrolls, then the question now confronting many spiritual pilgrims is how it came about that these obviously diverse theologies, represented in the so called Old and New Testaments, were moulded into only one "orthodox" result. In what way and to what degree were the many Christian groups different and distinctive from one another, as well as from other Jewish groups? Furthermore, what was the influence of other religions, Judaism, the Mysteries, Gnostics and Philosophers on the. development, variety of groups and ultimately on the consolidation of "orthodox" soteriology? THE INFLUENCE OF SOME ANCIENT RELIGIOUS AND PHILOSOPHICAL TRADITIONS ON THE SOTERIOLOGY OF EARLY CHRISTIANITY PAGE I. -

Death Studiesy

JNDAE7 19(4) 205-272 (2001) ISSN 0891-4494 http://www.wkap.nl/journalhome.htm/0891-4494 Journal nof Lear -Death Studies Y s*4 Editor's Foreword * Bruce Greyson, M.D. The Near-Death Experience as a Shamanic Initiation: A Case Study ' J. Timothy Green, Ph.D. Near-Death Experience: Knowledge and Attitudes of College Students * Kay E. Ketzenberger, Ph.D., and Gina L. Keim, B.A. Prophetic Revelations in Near-Death Experiences* Craig R. Lundahl, Ph.D. Book Reviews: The Physics of Immortality: Modern Cosmology, God and the Resurrection of the Dead, by Frank J. Tipler * Reviewed by John Wren-Lewis Children of the New Millenium: Children's Near-Death Experiences and the Evolution of Humankind, by P .M. H. Atwater* Reviewed by Thomas A. Angerpointner, M.D., Ph.D. Children of the New Millenium: Children's Near-Death Experiences and the Evolution of Humankind, by P .M. H. Atwater* Reviewed by Harold A. Widdison, Ph.D. Letters to the Editor ' V Krishnan and Bogomir Golobi, Volume 19, Number 4, Summer 2001 Editor Bruce Greyson, M.D., University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA Consulting Editors James E. Alcock, Ph.D., C.Psych., York University, Toronto, Ont. Carlos Alvarado, Ph.D., ParapsychologyFoundation, New York, NY Boyce Batey, Academy of Religion and Psychical Research, Bloomfield, CT Carl B. Becker, Ph.D., Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan Paul Bernstein, Ph.D., Chelsea, MA Diane K. Corcoran, R.N., Ph.D., Senior University, Richmond, B.C. Elizabeth W. Fenske, Ph.D., Spiritual Frontiers Fellowship International, Philadelphia,PA John C. Gibbs, Ph.D., The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH Stanislav Grof, M.D., Ph.D., CaliforniaInstitute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA Michael Grosso, Ph.D., New Jersey City University, Jersey City, NJ Bruce J. -

Soul Searchers

Soul Searchers Paranormal Magazine October 2015 ~ Issue 10 Listen Live Mondays from 11pm Soul Searchers Paranormal Magazine – October 2015- 1 Contents Note from the Editor page 3 Halloween Down Under page 4 Camperdown Cemetery page 6 An Investigation discussing Similarities in the Near Death Experience page 10 Wes Craven, Horror Maestro, Dies at 76 page 22 Does religion play a part in Ghost Research page 24 Paranormal Research page 28 Aussie Paranormal Book Corner page 38 Access Paranormal page 40 SOuL Searchers Parapsychology Course page 41 Soul Searchers Advertising & Deadlines page 43 . Soul Searchers Paranormal Magazine – October 2015- 2 Hello everyone, it has been a while since I last published an issue of Soul Searchers Magazine, the last 12 months of my life has been particularly challenging to say the least. There were so many things to sort out that I had to temporarily drop some of my projects and sadly Soul Searchers Paranormal Magazine was placed in hibernation. The good news is that the magazine is back and starting its resurrection with a Halloween issue. I am looking forward to publishing some exciting new articles hopefully with your support. So why not let us showcase your articles and photos. Submitting your articles for consideration is easy. Just send an inquiry or the completed work to [email protected]. Janine Donnellan Soul Searchers Paranormal Magazine – October 2015- 3 Halloween Down Under Soul Searchers Paranormal Magazine – October 2015- 4 As the northern hemisphere is gearing up for rebirth. It was a time of reverence and an ideal Halloween, Australia is slowly starting to catch on time to have contact with the dead.