An Analysis of 17Th-Century Ethiopian Pigments Anaïs Wion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

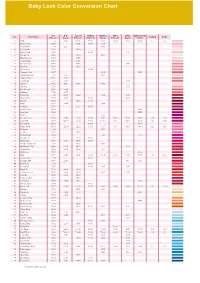

Baby Lock Color Conversion Chart

Tacony_quickguide_37-コピー 05.7.6 9:01 AM ページ 37 Baby Lock Color Conversion Chart R.A. R.A. Isacord Madeira Madeira Sulky Sulky Güetermann No. Color Name Polyester Rayon Polyester Polyneon Rayon Polyester Rayon Dekor Country Embr. 1 Pink 5523 2223 *0180 1921 1121 1224 1108 *4830 155 085 2 Dusty Rose 5675 2155 1816 1108 3 Petal Pink 7701 2255 1015 4 Light Pink 9030 1860 5 Light Coral 9078 1915 1148 6 Ginger Jar 9080 2170 1115 7 Heather Mist 9070 1755 8 Champagne 9063 2051 9 Dark Mauve 9015 2153 1119 10 Heather 9164 2152 11 Neon Pink 5711 1948 12 Comfort Pink 9077 1119 5435 13 Mountain Rose 5795 2373 1315 14 Cherry Pink 5544 2244 15 Carnation 5537 2509 1188 16 Salmon 9073 2553 1840 1018 17 Shrimp 5546 1154 18 Dark Coral 9065 2246 19 Bitteroot 7709 2277 20 Burgundy 5549 2249 2022 1182 1169 21 Warm Wine 5796 2622 1782 1309 22 Russet 5552 2123 1781 23 Plum 9055 2498 1389 24 Maroon 5676 2115 1919 25 Royal Crest 9162 5400 26 Hot Pink 5560 5385 27 Ruby 5797 1183 28 Dark Fuchsia 5804 2504 *2300 1984 1383 1533 1533 *4810 126 107 29 Carmine 5561 *2419 2300 1986 *1081 1511 *1511 5315 158 807 30 Dark Pink 9161 1994 4810 31 Deep Rose 9168 *2508 2520 1721 *1117 1154 1307 *4941 024 086 32 Begonia 5528 1117 33 Azalea 7712 2220 34 Rubine Red 9012 1186 4740 35 Strawberry 5732 2320 1910 36 Devil Red 7706 2507 1906 1986 37 Candy Apple Red 5807 1805 1081 38 Hollyhock Red 9006 2267 1912 1311 39 Toasty Red 9002 2418 1902 1181 40 Wild Fire 5567 4700 41 Red 5678 2505 2101 1637 *1037 1037 *1037 *4740 149 800 42 Jockey Red 5581 1747 43 Radiant Red 5566 2219 561 4731 -

Vermilion Category: Alchemy Therasia Von Tux, Barony 1000 Eyes Specific Art Form: Pigment This Is the Sept 2001 Revised Edition (One Small “Oops” Corrected)

Vermilion Category: Alchemy Therasia von Tux, Barony 1000 Eyes specific art form: pigment this is the Sept 2001 revised edition (one small “oops” corrected) Entry contents: 1 vial vermilion/cinnabar (POISON!!! PLEASE DON"T OPEN THE BOTTLE) 1 piece cinnabar 1 copy of Artists' Pigments, for the Gettens et al. article (a copy of Cennini can be found with my "St. George" shield, in the Fine Arts category; copies of Pliny and Theophilus can be found with my silver entry, in the Alchemy category) A piece of cinnabar collected by a friend and on display at the McLaughlin Mine, Napa Co., CA (It's a lot prettier than most of my samples) The first known mention of mercuric sulfide as a mineral is in Theophratus's Lapidary. Theophrastus called it cinnabar, which is the name still in use today. The Romans called it minium, and it was so valuable as a red pigment that the Roman government made it a nationalized monopoly and regulated the price.1 It does need to be said that the Romans used the name minium for any high-quality mineral red, regardless of whether it was cinnabar or hematite.2 Minium was being adultrated with "red lead" as early as Imperial Rome, though it is difficult to determine whether Pliny meant red litharge or lead carbonate. Adulteration continued until the name shifted, and came to mean just red lead by Early Gothic. 3, 4 1 Pliny, Book XXXIII: sections XXXVI-XLI, using the Loeb numbering system. 2 Ibid. 3 Ibid. 4 Though historians would quibble about this, I tend to prefer to the art history divisions of history rather than the academic history divisions. -

A Third Sex-Linked Lethal Factor in Drosophila T

A THIRD SEX-LINKED LETHAL FACTOR IN DROSOPHILA T. H. MORGAN Department of ZoBlogy, Columbia University THREE FIGURES In an experiment (reported in the Jour. Exp. Zool., page 390, November, 1911) in which three sex-linked characters were in- volved, namely, white eyes, vermilion eyes and miniature wings, certain results were obtained involving double crossing-over. The more recent results indicate that double crossing-over was excessive in this experiment.l A white miniature male had been mated to a vermilion pink (‘orange’) female. The daughters were wild type (red, long) and the sons vermilion (long). The two sex- chromosomes of these daughters contain respectively the genes for white (w), red (V), and miniature (m); and for red (W), and vermilion (v), and long (M). All later work has shown the order of the genes here involved is white, vermilion, miniature, as shown in diagram 1. On this basis, the results of the previous experiment in terms of cross-overs would be as follows: Total Per cent Non-cross-overs (vermilion and ver. pink males) 333 74.7 Single cross-overs between white and vermilion (min. and min. pink males). 81 18.2 Single cross-overs between vermilion and min. (verm. min. and ver. min. pink males). 11 2.4 Double cross-overs (wild type and pink males). 21 4.7 Instead of giving fewer double cross-overs than singles, accord- ing to expectation, the number of doubles was twice that of singles, and for numbers as large as these this difference cannot be due to 1 In the analysis on page 392 the large C in ‘sperm no X’ should be small c. -

Genetics and Cytology of <Emphasis Type="Italic">Drosophila Subobscura

GENETICS AND CYTOLOGY OF DROSOPHILA SUBOBSCURA III. TRANSPLANTATION OF EYE-BUDS BETWEEN DROSOPHILA SUBOBSGURA AND DROSOPtlILA MELANOGASTER By J. M. RENDEL, National A~imal B,reeding Research Organization% Institute of Animal Genetics; Edinburgh, AND A. C. E. SULEY, Department of Biomet'ry, University Oollege, London There are in Drosophila subobscura four bl'ight red eye-colour mutants, vermilio~ (chromo- some I, sex-linked), scarlet (chr. II), poppy (chr. IV), and cherry (chr. u An attempt is being made to homologize some of these, and certain other genes, with genes in D. melanogaster, where the phenotypically similar genes, vermilion, cinnabar, cardinal and scarlet do not behave identically in transplantation experiments. As the method depends on the work of Ephrussi & Beadle, the points in their results with D. mclanogaster relevant to this work will be briefly summarized (see Table 1). Implants from larvae of most eye-colour mutants are autonomous with respect to their colour developed in wild-type hosts. But implants from vermilion and cinnabar develop the browner colour of the wild-type host's eye. A genetically vermilion eye also develops the wild-type colour in a cinnabar host, though cinnabar in vermilion is autonomous. Ephrussi & Beadle therefore suggested that two diffusible substances essential to the development of the brown pigment were supplied by the wild-type host. The vermilion mutant lacks one, the v+ substance, which has since been shown to be kymtrenine, and cinnabar lacks the cn+ substance. The behaviour of the reciprocal transplants between the two mutants suggests that the v+ substance is the precursor of the cn + substance. -

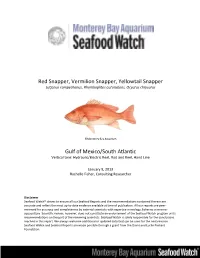

Red Snapper, Vermilion Snapper, Yellowtail Snapper Gulf of Mexico

Red Snapper, Vermilion Snapper, Yellowtail Snapper Lutjanus campechanus, Rhomboplites aurorubens, Ocyurus chrysurus ©Monterey Bay Aquarium Gulf of Mexico/South Atlantic Vertical Line: Hydraulic/Electric Reel, Rod and Reel, Hand Line January 9, 2013 Rachelle Fisher, Consulting Researcher Disclaimer Seafood Watch® strives to ensure all our Seafood Reports and the recommendations contained therein are accurate and reflect the most up-to-date evidence available at time of publication. All our reports are peer- reviewed for accuracy and completeness by external scientists with expertise in ecology, fisheries science or aquaculture. Scientific review, however, does not constitute an endorsement of the Seafood Watch program or its recommendations on the part of the reviewing scientists. Seafood Watch is solely responsible for the conclusions reached in this report. We always welcome additional or updated data that can be used for the next revision. Seafood Watch and Seafood Reports are made possible through a grant from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. 2 Final Seafood Recommendation Although there are many snappers caught in the U.S., only the three most commercially important species relative to landed weight and value (red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus), vermilion snapper (Rhomboplites aurorubens), and yellowtail snapper (Ocyurus chrysurus) are discussed here. This report discusses snapper caught in the South Atlantic (SA) and Gulf of Mexico (GOM) by vertical gear types including hydraulic/electric reel, rod and reel, and handline. Snapper caught by bottom longline in the GOM and SA will not be discussed since it makes up a statistically insignificant proportion of the total snapper catch in the GOM and in the SA bottom longline fishing in waters shallower than 50 fathoms, where snapper are generally caught, is prohibited. -

Shorter Articles and Discussion Simplified Mendelian Formulae R

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Agronomy & Horticulture -- Faculty Publications Agronomy and Horticulture Department 1913 Shorter Articles and Discussion Simplified Mendelian Formulae R. A. Emerson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/agronomyfacpub Part of the Agricultural Science Commons, Agriculture Commons, Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons, Botany Commons, Horticulture Commons, Other Plant Sciences Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Emerson, R. A., "Shorter Articles and Discussion Simplified Mendelian Formulae" (1913). Agronomy & Horticulture -- Faculty Publications. 904. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/agronomyfacpub/904 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Agronomy and Horticulture Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agronomy & Horticulture -- Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SHORTER ARTICLES AND DISCUSSION SIMPLIFIED MENDELIAN FORMUL-7T I wFs somewhat surprised by 'Morgan's and Castle's sugges- tions for a simplification of Mlendelian formulve.1- My surprise was not occasioned so much by the forms these suggestions took as by the fact that any pronounced changes were deemed neces- sary. I had not only employed the usual formula in my own work but had found no difficulty worth mentioning in under- standing the formula used by most other workers in Mendelian fields. My experience with students in elementary courses in genetics had not prepared me for the idea that such formula were particularly difficult. Nevertheless I believe in simplifying the formule if some system can be found that will be applicable to all sorts of Mendelian inheritance. -

REDDISH-A FREQUENTLY "M11UTATING" CHARACTER in DROSOPIIILA VIRILIS X by M

VoL. 12, 1926 GENETICS: M. DEMEREC 1.1 heterozygous for certain other white lines (called B whites), abnormal ratios are thrown by RI and by Pn if the latter appears to have the constitution Pp2. The mutant Wy has occurred in the offspring of parents heterozygous for Line 1 and B whites; but never in the offspring of Line 1, of A whites, nor of parents heterozygous for Line 1 and A whites. Crosses between Line 1 and three different B whites have given F1 plants with- normal pollen and ovules. 1 Blakeslee, A. F., 1924. "Distinction between Primary and Secondary Mutants," these PROCEEDINGS, 10, 109-116. 2 Belling, J. and A. F. Blakeslee, 1924. "The Configurations and Sizes of the Chromo- somes in the Trivalents of 25-Chromosome Daturas,'' these PROCgZDINGS, 10, 116-120. 3 Blakeslee, A. F., 1924. Quoted in Yearbook of Carnegie Institution of Washington, No. 23, 1924, pp. 24-27. 4 Belling, J., 1924. Quoted in Yearbook of Carnegie Institution of Washington, No. 23, 1924, pp. 28-30. 5 Belling, J., 1914. "On the Inheritance of Semi-sterility in Certain Hybrid Plants." Zeitsch. ind. Abst. Vererbungslehre, 9, Heft 5, 303-342. 6 Belling, J., 1915. Rept. Fla. Agr. Exp. Sta. for 1914. Pp. 81-105. Belling, J., 1925. "A Unique Result in Certain Species Crosses." Zeitsch. ind. Abst. Vererbungslehre. (In press.) 8 Belling, J., 1925. "On the Origin of Species in Flowering Plants." Nature, 116, 279. (Aug. 22). REDDISH-A FREQUENTLY "M11UTATING" CHARACTER IN DROSOPIIILA VIRILIS X By M. DRMEREC DEPARTMENT OF GENETICS, CARNEGIE INSTITUTION OF WASHINGTON, COLD SPRING HARBOR, N. -

Watercolor Substitution Cheat Sheet * = Lindsay Recommended Color

Watercolor Substitution Cheat Sheet * = Lindsay Recommended color *Phthalo Blue (Strong cool-green leaning-blue) Prussian Blue (also look for that pigment) AKA Pthalo blue GS Cyan Blue or green shade. Cerulean Blue (if it looks dark: Mission Gold) Helio Cerulean **This colors is great for mixing green when Winsor Blue (Winsor & Newton) paired with a cool yellow. Intense Blue (Winsor & Newton/Cotman) Azure (Yarka/White Nights) Turquoise Indigo (deep cool blue grey) Indanthrone Blue Payne's Grey+Prussian Blue *Ultramarine Blue (warm, purple bias red) Colbalt Blue Pthalo blue Red Shade (not my fave substitute) **This color is good for mixing violet with a cool Poland Blue red or gray with burnt sienna. ***This color granulates for textured washes. Cerulean Blue (Less intense cool blue) Manganese Blue Phthalo blue + white Cinerous Blue (Sennelier) *Quinacridone Rose (Cool red with violet Alizarian Crimson undertones) Carmine **This color makes lovely purples and mauve Crimson lake with blues. Rose Madder (weaker than AZ) *Cadmium Red or Cadmium red light Vermilion (Warm red with orange undertones) Scarlet Napthol Red **This color makes beautiful oranges when mixed Bright Red/ Brilliant Red with warm yellows. Pyrrole Red Permanent Rose Magenta *Cadmium Yellow (warm yellow) Gamboge Cadmium yellow medium/Cadmium yellow deep Indian Yellow Permanent yellow deep **This color makes beautiful oranges when mixed with warm reds or peach with cool reds *Hansa Yellow Light (cool yellow) Lemon Yellow (cool yellow) Cadmium yellow light, pale or Cadmium -

69(;:- / 1 Keith Roy, Parish a Inistrator Vermilion Parish Police Jury

Vermilion Parish Police Jury Resolution No. 10 WHEREAS, The Vermilion Parish Police Jury agrees to relinquish ownership of whatever rights it may own, with the exception of any and all mineral rights, in and to the following described property, and to relinquish all duties, obligations, and responsibilities for the operation and maintenance, and liabilities associated therewith to the State of Louisiana through the Department of Transportation and Development (" Department"): The portion of relocated State Route LA 331, beginning at a point located approximately 0.04 miles south of the new intersection with the local road known as St. Agnes Rd, and traversing northwesterly on a new alignment approximately 0.21 miles to its connection back to existing State Route LA 331, and further identified in Exhibit" C", highlighted in turquois and pink. WHEREAS, The Vermilion Parish Police Jury, in exchange for the acceptance by the Department ofthe aforesaid described property, agrees to accept ownership of whatever rights the Department may own, with the exception of any and all mineral rights, in and to the following described property, and agrees to accept all duties, obligations, and responsibilities for the operation and maintenance and liabilities associated therewith, for their use as parish road( s). The portion of relocated State Route LA 331, beginning at a point located approximately 0.04 miles south ofthe new intersection with the local road known as St. Agnes Rd, and traversing along existing alignment approximately 0.21 miles to its intersection with local road known as Eve Rd, and further identified in Exhibit" C", highlighted in yellow, blue and orange. -

Christian Visual Culture in Medieval Ethiopia: Overview, Trends and Issues

chapter 12 Christian Visual Culture in Medieval Ethiopia: Overview, Trends and Issues Claire Bosc-Tiessé 1 Some Historiographical Trends The Christian Church established itself in Ethiopia during the fourth cen- tury, and one can suppose that it stimulated a movement of textual copying, the importation or manufacture of vestments and liturgical objects, the con- struction of churches and perhaps the creation of paintings. Under Coptic authority until the twentieth century, this Church developed specific charac- teristics. While the remains of Aksumite-era churches have been excavated, there remains nothing from the late antique period in terms of monumen- tal paintings. Members of the family of the Prophet Muhammad in exile in Ethiopia are reported to have seen ornaments in the interior of the cathedral of Aksum, which would have occurred in the seventh century, but what remains to us for study are the illuminated Gospel books of the monastery of Abba Gärima. It is thus easier to trace what medieval Christian Ethiopia inherited from the Aksumite era in architecture than in painting. It bears mention that all the surviving artistic productions of the medieval Christian kingdom con- cern the religious sphere, including representations of royalty which exist only in this context. Some efforts to survey the field have been made, in coffee-table books au- thored by scholars, in the introductory essays to exhibition catalogs or in some entries related to art history in the Encyclopaedia Aethiopica from 2003 forward. That said, no analytical synthesis of medieval Ethiopian art history – recall- ing that the Ethiopian medieval area also extends over part of the territory of present-day Eritrea – has yet been written. -

Effort to Obtain Data of This Nature in Regard to the Process of Eye of The

THE EYE-PIGMENTARY SYSTEM OF DROSOPHILA VIII. SERIES OF MULTIPLE ALLELES D. J. NOLTE Deportment of Zoology, University of the Witwatersrond Received3.vi.58 THE study of multiple alleles at a locus is of prime importance for research on the theory of the gene—its qualitative and quantitative effects and the relationship between function and mutation. In an effort to obtain data of this nature in regard to the process of eye pigmentation in Drosophila melanogaster nine series of multiple alleles, that is, at the loci of scarlet, vermilion, cinnabar, brown, pink, carna- tion, garnet, raspberry and prune, were investigated for the histology of the four eye-pigment regions and the spectrophotometric properties of the red and brown pigments. These methods have been fully described (Nolte, 1952,1954).These multiple alleles consisted of the following :—scarlct (st) and scarlet-spotted (st'P) ; vermilion (v) and vermilion361 (v361) ; cinnabar (en) and cinnabar3sk (cn3sk) ; brown (bw), brownzb (bw2b), brown-dominant (bwD) and brown4 (bw4); pink (p) and pink-peach (pv) ; carnation (car) and carnationz (carz) garnet (g), garnetz (g2), garnet3 (g3) and garnet4 (g4) ; raspberry (ras), raspberryz (rasz) and raspberry3 (ras3) ; prune (pn) and prune2 (pnz). 2.OBSERVATIONS (I)Phenotype Themacroscopic phenotypes of some of these alleles, in the stocks maintained in this laboratory, differ somewhat from the descriptions as given by Bridges and Brehme (i44), as will duly be noted. The eye-colour of st3 is very like that of the wild-type, with perhaps a pitted effect, i.e., small dark spots, but is not speckled; the combina- tion stsP/st is bright red and not speckled. -

African & Contemporary Art Collections

AFRICAN & CONTEMPORARY ART COLLECTIONS Skunder Boghossian Time Cycle III 1981 Embossed bark and sand with collage on board 48 × 47 ⅞ × 2¾ in. (121.9 × 121.6 × 7 cm) Museum purchase, funds provided by the Caroline Julier and James G. Richardson Acquisition Fund and the Charles P. and Caroline Ireland Foundation 2006.3 Skunder Boghossian has been hailed as a leading artist and educator of African descent who has had a profound influence on artists in the United States and in his homeland, Ethiopia. Boghossian was born in Addis Ababa in 1937. His art training began in Ethiopian art schools that departed from traditional art by encouraging representation of daily life. In 1954 he received a national award for his art, and in 1955 he was awarded an imperial scholarship to study in England. After two years at Saint Martins School of Art and the Slade School of Art in London, he moved to France, where he spent nine years studying and teaching at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris. Boghossian’s years in Europe were critical to his intellectual and artistic development. In France he was immersed in the Negritude movement and neosurrealism, both of which had a lasting impact on his art. A year after his return to Ethiopia, in 1965, he was offered a position at the Addis Ababa Fine Arts School, and he taught there until 1969. In 1965 the Museum of Modern Art in New York acquired one of his paintings, and in 1966 a solo exhibition in Addis Ababa revealed Boghossian as a pioneer of modern Ethiopian art.