Red Snapper, Vermilion Snapper, Yellowtail Snapper Gulf of Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Text in Pdf Format

Vol. 9: 185–192, 2010 AQUATIC BIOLOGY Published online May 12 doi: 10.3354/ab00250 Aquat Biol Microparasite ecology and health status of common bluestriped snapper Lutjanus kasmira from the Pacific Islands Thierry M. Work1,*, Matthias Vignon2, 3, Greta S. Aeby4 1US Geological Survey, National Wildlife Health Center, Honolulu Field Station, PO Box 50167, Honolulu, Hawaii 96850, USA 2Centre de Biologie et d’Ecologie Tropicale et Méditerranéenne, UMR 5244 CNRS-EPHE-UPVD, avenue Paul Alduy, 66860 Perpignan Cedex, France 3Centre de Recherches Insulaires et Observatoire de l’Environnement (CRIOBE), USR 3278 CNRS-EPHE, BP 1013 Papetoia, Moorea, French Polynesia 4Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology, PO Box 1346, Kaneohe, Hawaii 96744, USA ABSTRACT: Common bluestriped snappers Lutjanus kasmira were intentionally introduced into Hawaii from the South Pacific in the 1950s and have become well established throughout the archi- pelago. We examined health, prevalence and infection intensity of 2 microparasites, coccidia and epitheliocystis-like organisms (ELO), in L. kasmira from their introduced and native range including the islands where translocated fish originated (Tahiti and Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia) and from several other islands (American Samoa, Fiji and New Caledonia). In addition, we did a longitu- dinal survey of these parasites in the introduced range. Coccidia and ELO were widely distributed and were found on all islands except for New Caledonia. Health indices, as measured by overall organ lesions, body condition and parasite intensity, indicated that fish from Samoa were the least healthy, and fish from Midway (Hawaiian Archipelago) were the healthiest. Microparasite diversity was highest on Midway and Hawaii and lowest on New Caledonia. -

Reef Snappers (Lutjanidae)

#05 Reef snappers (Lutjanidae) Two-spot red snapper (Lutjanus bohar) Mangrove red snapper Blacktail snapper (Lutjanus argentimaculatus) (Lutjanus fulvus) Common bluestripe snapper (Lutjanus kasmira) Humpback red snapper Emperor red snapper (Lutjanus gibbus) (Lutjanus sebae) Species & Distribution Habitats & Feeding The family Lutjanidae contains more than 100 species of Although most snappers live near coral reefs, some species tropical and sub-tropical fi sh known as snappers. are found in areas of less salty water in the mouths of rivers. Most species of interest in the inshore fi sheries of Pacifi c Islands belong to the genus Lutjanus, which contains about The young of some species school on seagrass beds and 60 species. sandy areas, while larger fi sh may be more solitary and live on coral reefs. Many species gather in large feeding schools One of the most widely distributed of the snappers in the around coral formations during daylight hours. Pacifi c Ocean is the common bluestripe snapper, Lutjanus kasmira, which reaches lengths of about 30 cm. The species Snappers feed on smaller fi sh, crabs, shrimps, and sea snails. is found in many Pacifi c Islands and was introduced into They are eaten by a number of larger fi sh. In some locations, Hawaii in the 1950s. species such as the two-spot red snapper, Lutjanus bohar, are responsible for ciguatera fi sh poisoning (see the glossary in the Guide to Information Sheets). #05 Reef snappers (Lutjanidae) Reproduction & Life cycle Snappers have separate sexes. Smaller species have a maximum lifespan of about 4 years and larger species live for more than 15 years. -

A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico And

A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes THIRD EDITION GSMFC No. 300 NOVEMBER 2020 i Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission Commissioners and Proxies ALABAMA Senator R.L. “Bret” Allain, II Chris Blankenship, Commissioner State Senator District 21 Alabama Department of Conservation Franklin, Louisiana and Natural Resources John Roussel Montgomery, Alabama Zachary, Louisiana Representative Chris Pringle Mobile, Alabama MISSISSIPPI Chris Nelson Joe Spraggins, Executive Director Bon Secour Fisheries, Inc. Mississippi Department of Marine Bon Secour, Alabama Resources Biloxi, Mississippi FLORIDA Read Hendon Eric Sutton, Executive Director USM/Gulf Coast Research Laboratory Florida Fish and Wildlife Ocean Springs, Mississippi Conservation Commission Tallahassee, Florida TEXAS Representative Jay Trumbull Carter Smith, Executive Director Tallahassee, Florida Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas LOUISIANA Doug Boyd Jack Montoucet, Secretary Boerne, Texas Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Baton Rouge, Louisiana GSMFC Staff ASMFC Staff Mr. David M. Donaldson Mr. Bob Beal Executive Director Executive Director Mr. Steven J. VanderKooy Mr. Jeffrey Kipp IJF Program Coordinator Stock Assessment Scientist Ms. Debora McIntyre Dr. Kristen Anstead IJF Staff Assistant Fisheries Scientist ii A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes Third Edition Edited by Steve VanderKooy Jessica Carroll Scott Elzey Jessica Gilmore Jeffrey Kipp Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission 2404 Government St Ocean Springs, MS 39564 and Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission 1050 N. Highland Street Suite 200 A-N Arlington, VA 22201 Publication Number 300 November 2020 A publication of the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award Number NA15NMF4070076 and NA15NMF4720399. -

Fish Spawning Aggregations

Fish Spawning Aggregations a focal point of fisheries management and marine conservation in Mexico Photo: Octavio Aburto Authorship Brad Erisman – Coastal Fisheries Research Program, University of Texas Marine Science Institute, 750 Channel View Drive, Port Aransas, TX 78373 William Heyman – LGL Ecological Research Associates, Inc., 4103 S. Texas Avenue, Bryan TX 77802 Stuart Fulton – Comunidad y Biodiversidad, Isla del Peruano 215, Lomas de Miramar, Guaymas, Sonora, Mexico Timothy Rowell – Gulf of California Marine Program, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92037 Illustrations – Larry Allen and Madeline Wukusick Graphic Design – Madeline Wukusick | www.communique.design Photography – Octavio Aburto, Richard Barnden, Douglas David Seifert, Walt Stearns, Cristina Limonta, Alfredo Barroso Citation – Erisman, B., W.D. Heyman, S. Fulton, and T.Rowell 2018. Fish spawning aggregations: a focal point of fisheries management and marine conservation in Mexico. Gulf of California Marine Program, La Jolla, CA. 24 p. Email Contact: Brad Erisman, [email protected] Fish Spawning Aggregations // 2 Contents > Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 > What are fish spawning aggregations (FSAs)? ............................................................................................................ 5 > What kinds of fishes form FSAs? ................................................................................................................................ -

Cobia Database Articles Final Revision 2.0, 2-1-2017

Revision 2.0 (2/1/2017) University of Miami Article TITLE DESCRIPTION AUTHORS SOURCE YEAR TOPICS Number Habitat 1 Gasterosteus canadus Linné [Latin] [No Abstract Available - First known description of cobia morphology in Carolina habitat by D. Garden.] Linnaeus, C. Systema Naturæ, ed. 12, vol. 1, 491 1766 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) Ichthyologie, vol. 10, Iconibus ex 2 Scomber niger Bloch [No Abstract Available - Description and alternative nomenclature of cobia.] Bloch, M. E. 1793 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) illustratum. Berlin. p . 48 The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the Under this head was to be carried on the study of the useful aquatic animals and plants of the country, as well as of seals, whales, tmtles, fishes, lobsters, crabs, oysters, clams, etc., sponges, and marine plants aml inorganic products of U.S. Commission on Fisheries, Washington, 3 United States. Section 1: Natural history of Goode, G.B. 1884 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) the sea with reference to (A) geographical distribution, (B) size, (C) abundance, (D) migrations and movements, (E) food and rate of growth, (F) mode of reproduction, (G) economic value and uses. D.C., 895 p. useful aquatic animals Notes on the occurrence of a young crab- Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 4 eater (Elecate canada), from the lower [No Abstract Available - A description of cobia in the lower Hudson Eiver.] Fisher, A.K. 1891 Wild (Atlantic/Pacific) 13, 195 Hudson Valley, New York The nomenclature of Rachicentron or Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum Habitat 5 Elacate, a genus of acanthopterygian The universally accepted name Elucate must unfortunately be supplanted by one entirely unknown to fame, overlooked by all naturalists, and found in no nomenclator. -

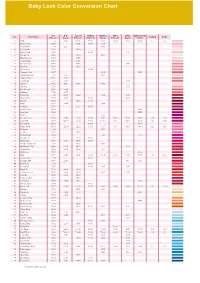

Baby Lock Color Conversion Chart

Tacony_quickguide_37-コピー 05.7.6 9:01 AM ページ 37 Baby Lock Color Conversion Chart R.A. R.A. Isacord Madeira Madeira Sulky Sulky Güetermann No. Color Name Polyester Rayon Polyester Polyneon Rayon Polyester Rayon Dekor Country Embr. 1 Pink 5523 2223 *0180 1921 1121 1224 1108 *4830 155 085 2 Dusty Rose 5675 2155 1816 1108 3 Petal Pink 7701 2255 1015 4 Light Pink 9030 1860 5 Light Coral 9078 1915 1148 6 Ginger Jar 9080 2170 1115 7 Heather Mist 9070 1755 8 Champagne 9063 2051 9 Dark Mauve 9015 2153 1119 10 Heather 9164 2152 11 Neon Pink 5711 1948 12 Comfort Pink 9077 1119 5435 13 Mountain Rose 5795 2373 1315 14 Cherry Pink 5544 2244 15 Carnation 5537 2509 1188 16 Salmon 9073 2553 1840 1018 17 Shrimp 5546 1154 18 Dark Coral 9065 2246 19 Bitteroot 7709 2277 20 Burgundy 5549 2249 2022 1182 1169 21 Warm Wine 5796 2622 1782 1309 22 Russet 5552 2123 1781 23 Plum 9055 2498 1389 24 Maroon 5676 2115 1919 25 Royal Crest 9162 5400 26 Hot Pink 5560 5385 27 Ruby 5797 1183 28 Dark Fuchsia 5804 2504 *2300 1984 1383 1533 1533 *4810 126 107 29 Carmine 5561 *2419 2300 1986 *1081 1511 *1511 5315 158 807 30 Dark Pink 9161 1994 4810 31 Deep Rose 9168 *2508 2520 1721 *1117 1154 1307 *4941 024 086 32 Begonia 5528 1117 33 Azalea 7712 2220 34 Rubine Red 9012 1186 4740 35 Strawberry 5732 2320 1910 36 Devil Red 7706 2507 1906 1986 37 Candy Apple Red 5807 1805 1081 38 Hollyhock Red 9006 2267 1912 1311 39 Toasty Red 9002 2418 1902 1181 40 Wild Fire 5567 4700 41 Red 5678 2505 2101 1637 *1037 1037 *1037 *4740 149 800 42 Jockey Red 5581 1747 43 Radiant Red 5566 2219 561 4731 -

Final Report Characterization of Commercial Reef Fish Catch And

SEDAR 15-RD07 Final Report Characterization of commercial reef fish catch and bycatch off the southeast coast of the United States. CRP Grant No. NA03NMF4540416 Funding amount: $100,000 Federal $4,130 Match Patrick J. Harris and Jessica Stephen Marine Resources Research Institute South Carolina Department of Natural Resources 217 Fort Johnson Road P.O. Box 12559 Charleston, SC 29412 I. Characterization of commercial reef fish catch and bycatch off the southeast coast of the United States. Patrick J. Harris, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Charleston, SC 29412. Grant Number: NA03NMF4540416 July 2005. II. Abstract There is clearly a need to characterize the entire catch of commercial fishermen and compare differences in abundance and species diversity to what is caught in fishery-independent gear. As we move towards a multi-species management approach, these types of data are essential. In addition, estimates of release mortality are needed for stock assessments but currently this is not being measured for fishery-dependent data. Many reef fishes captured at depths greater than ~ 20 m often have problems submerging when released by commercial fishermen. The goal of the research project was to characterize the entire (retained and discarded) catch of reef fishes from a selected commercial fisherman including total catch composition and disposition of fishes that were released. During April- November 2004, Captain Mark Marhefka dedicated one fishing trip (5-7 day duration) each month to the collection of fishery-dependent data. Date, location and collection number were recorded for each site fished by Captain Marhefka using a PDA equipped with a GPS. -

RNA Detection Technology for Applications in Marine Science: Microbes to Fish Robert Michael Ulrich University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 6-25-2014 RNA Detection Technology for Applications in Marine Science: Microbes to Fish Robert Michael Ulrich University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons, and the Molecular Biology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ulrich, Robert Michael, "RNA Detection Technology for Applications in Marine Science: Microbes to Fish" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/5321 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RNA Detection Technology for Applications in Marine Science: Microbes to Fish by Robert M. Ulrich A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Marine Science University of South Florida Major Professor: John H. Paul, Ph.D. Valerie J. Harwood, Ph.D. Mya Breitbart, Ph.D. Christopher D. Stallings, Ph.D. David E. John, Ph.D. Date of Approval June 25, 2014 Keywords: NASBA, grouper, Karenia mikimotoi, Enterococcus Copyright © 2014, Robert M. Ulrich DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my fiancée, Dr. Shannon McQuaig for inspiring my return to graduate school and her continued support over the last four years. On no other porch in our little town have there been more impactful scientific discussions, nor more words of encouragement. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I gratefully acknowledge the many people who have encouraged and advised me throughout my graduate studies. -

Andrea RAZ-GUZMÁN1*, Leticia HUIDOBRO2, and Virginia PADILLA3

ACTA ICHTHYOLOGICA ET PISCATORIA (2018) 48 (4): 341–362 DOI: 10.3750/AIEP/02451 AN UPDATED CHECKLIST AND CHARACTERISATION OF THE ICHTHYOFAUNA (ELASMOBRANCHII AND ACTINOPTERYGII) OF THE LAGUNA DE TAMIAHUA, VERACRUZ, MEXICO Andrea RAZ-GUZMÁN1*, Leticia HUIDOBRO2, and Virginia PADILLA3 1 Posgrado en Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México 2 Instituto Nacional de Pesca y Acuacultura, SAGARPA, Ciudad de México 3 Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México Raz-Guzmán A., Huidobro L., Padilla V. 2018. An updated checklist and characterisation of the ichthyofauna (Elasmobranchii and Actinopterygii) of the Laguna de Tamiahua, Veracruz, Mexico. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 48 (4): 341–362. Background. Laguna de Tamiahua is ecologically and economically important as a nursery area that favours the recruitment of species that sustain traditional fisheries. It has been studied previously, though not throughout its whole area, and considering the variety of habitats that sustain these fisheries, as well as an increase in population growth that impacts the system. The objectives of this study were to present an updated list of fish species, data on special status, new records, commercial importance, dominance, density, ecotic position, and the spatial and temporal distribution of species in the lagoon, together with a comparison of Tamiahua with 14 other Gulf of Mexico lagoons. Materials and methods. Fish were collected in August and December 1996 with a Renfro beam net and an otter trawl from different habitats throughout the lagoon. The species were identified, classified in relation to special status, new records, commercial importance, density, dominance, ecotic position, and spatial distribution patterns. -

Seriola Dumerili (Greater Amberjack)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Diversity Seriola dumerili (Greater Amberjack) Family: Carangidae (Jacks and Pompanos) Order: Perciformes (Perch and Allied Fish) Class: Actinopterygii (Ray-finned Fish) Fig. 1. Greater amberjack, Seriola dumerili. [http://portal.ncdenr.org/web/mf/amberjack_greater downloaded 20 October 2016] TRAITS. The species Seriola dumerili displays rapid growth during development as a juvenile progressing to an adult. It is the largest species of the family of jacks. At adulthood, S. dumerili would typically weigh about 80kg and reach a length of 1.8-1.9m. Sexual maturity is achieved between the age of 3-5 years, and females may live longer and grow larger than males (FAO, 2016). S. dumurili are rapid-moving predators as shown by their body form (Fig. 1) (FLMNH, 2016). The adult is silvery-bluish in colour, whereas the juvenile is yellow-green. It has a characteristic goldish side line, as well as a dark band near the eye, as seen in Figs 1 and 2 (FAO, 2016; MarineBio, 2016; NCDEQ, 2016). DISTRIBUTION. S. dumerili is native to the waters of Trinidad and Tobago. Typically pelagic, found between depths of 10-360m, the species can be described as circumglobal. In other words, it is found worldwide, as seen in Fig. 3, though much more rarely in some areas, for example the eastern Pacific Ocean (IUCN, 2016). Due to this distribution, there is no threat to the population of the species, despite overfishing in certain locations. Migrations do occur, which are thought to be linked to reproductive cycles. -

Epinephelus Drummondhayi Goode and Bean, 1878 EED Frequent Synonyms / Misidentifications: None / None

click for previous page 1340 Bony Fishes Epinephelus drummondhayi Goode and Bean, 1878 EED Frequent synonyms / misidentifications: None / None. FAO names: En - Speckled hind; Fr - Mérou grivelé; Sp - Mero pintaroja. Diagnostic characters: Body depth subequal to head length, 2.4 to 2.6 times in standard length (for fish 20 to 43 cm standard length). Nostrils subequal; preopercle rounded, evenly serrate. Gill rakers on first arch 9 or 10 on upper limb, 17 or 18 on lower limb, total 26 to 28. Dorsal fin with 11 spines and 15 or 16 soft rays, the membrane incised between the anterior spines; anal fin with 3 spines and 9 soft rays; caudal fin trun- cate or slightly emarginate, the corners acute; pectoral-fin rays 18. Scales strongly ctenoid, about 125 lateral-scale series; lateral-line scales 72 to 76. Colour: adults (larger than 33 cm) dark reddish brown, densely covered with small pearly white spots; juveniles (less than 20 cm) bright yellow, covered with small bluish white spots. Size: Maximum about 110 cm; maximum weight 30 kg. Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Adults inhabit offshore rocky bottoms in depths of 25 to 183 m but are most common between 60 and 120 m.Females mature at 4 or 5 years of age (total length 45 to 60 cm).Spawning oc- curs from July to September, and a large female may produce up to 2 million eggs at 1 spawning. Back-calculated total lengths for fish aged 1 to 15 years are 19, 32, 41, 48, 53, 57, 61, 65, 68, 71, 74, 77, 81, 84, and 86 cm; the maximum age attained is at least 25 years, and the largest specimen measured was 110 cm. -

Molecular Authentication of Pargo Fillets Lutjanus Purpureus (Perciformes: Lutjanidae) by DNA Barcoding Reveals Commercial Fraud

Neotropical Ichthyology, 16(1): e170068, 2018 Journal homepage: www.scielo.br/ni DOI: 10.1590/1982-0224-20170068 Published online: 26 March 2018 (ISSN 1982-0224) Copyright © 2018 Sociedade Brasileira de Ictiologia Printed: 31 March 2018 (ISSN 1679-6225) Original article Molecular authentication of Pargo fillets Lutjanus purpureus (Perciformes: Lutjanidae) by DNA barcoding reveals commercial fraud Ivana Veneza1, Raimundo Silva1, Leilane Freitas1, Sâmia Silva1, Kely Martins1, Iracilda Sampaio2, Horacio Schneider2 and Grazielle Gomes1,2 The Caribbean Red Snapper (Pargo) Lutjanus purpureus is the most economically important snapper in Brazil, which is sold, among other forms, as frozen fillets. During the process of transformation into fillets there is the removal of the distinctive morphological traits, being able to favor the substitution by less valued species. In addition, there is no national legislation requiring the insertion of the specific name on the product label. However, according to a Normative Instruction (IN N ° 29/2015 MAPA) that correlates the common and specific names of the products destined to the national trade, in Brazil only L. purpureus and L. campechanus can be denominated “Pargo”. Thus, the DNA barcode tool was used to identify the fillets sold in north of Brazil, labeled “Pargo”, with the aid of sequences from the public and control databases. The results showed that among 142 fillets examined, 78% was identified as L. purpureus and 22% as Rhomboplites aurorubens, a snapper with low commercial value in the country, revealing commercial fraud. The molecular identification method successfully used in this study to authenticate fillets snappers may also be used by surveillance authorities in the quality control of processed fish products, towards ensuring consumer rights.