Stage Four Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity, Knowledge, and Valuation of Plants Used As Fermentation Starters

He et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2019) 15:20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-019-0299-y RESEARCH Open Access Diversity, knowledge, and valuation of plants used as fermentation starters for traditional glutinous rice wine by Dong communities in Southeast Guizhou, China Jianwu He1,2,3, Ruifei Zhang1,2, Qiyi Lei4, Gongxi Chen3, Kegang Li3, Selena Ahmed5 and Chunlin Long1,2,6* Abstract Background: Beverages prepared by fermenting plants have a long history of use for medicinal, social, and ritualistic purposes around the world. Socio-linguistic groups throughout China have traditionally used plants as fermentation starters (or koji) for brewing traditional rice wine. The objective of this study was to evaluate traditional knowledge, diversity, and values regarding plants used as starters for brewing glutinous rice wine in the Dong communities in the Guizhou Province of China, an area of rich biological and cultural diversity. Methods: Semi-structured interviews were administered for collecting ethnobotanical data on plants used as starters for brewing glutinous rice wine in Dong communities. Field work was carried out in three communities in Guizhou Province from September 2017 to July 2018. A total of 217 informants were interviewed from the villages. Results: A total of 60 plant species were identified to be used as starters for brewing glutinous rice wine, belonging to 58 genera in 36 families. Asteraceae and Rosaceae are the most represented botanical families for use as a fermentation starter for rice wine with 6 species respectively, followed by Lamiaceae (4 species); Asparagaceae, Menispermaceae, and Polygonaceae (3 species respectively); and Lardizabalaceae, Leguminosae, Moraceae, Poaceae, and Rubiaceae (2 species, respectively). -

HUNG LIU: OFFERINGS January 23-March 17, 2013

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contacts: December 12, 2012 Maysoun Wazwaz Mills College Art Museum, Program Manager 510.430.3340 or [email protected] Mills College Art Museum Announces HUNG LIU: OFFERINGS January 23-March 17, 2013 Oakland, CA—December 12, 2012. The Mills College Art Museum is pleased to present Hung Liu: Offerings a rare opportunity to experience two of the Oakland-based artist’s most significant large- scale installations: Jiu Jin Shan (Old Gold Mountain) (1994) and Tai Cang—Great Granary (2008). Hung Liu: Offerings will be on view from January 23 through March 17, 2013. The opening reception takes place on Wednesday, January 23, 2013 from 6:00–8:00 pm and free shuttle service will be provided from the MacArthur Bart station during the opening. Recognized as America's most important Chinese artist, Hung Liu’s installations have played a central role in her work throughout her career. In Jiu Jin Shan (Old Gold Mountain), over two hundred thousand fortune cookies create a symbolic gold mountain that engulfs a crossroads of railroad tracks running beneath. The junction where the tracks meet serves as both a crossroads and 1 terminus, a visual metaphor of the cultural intersection of East and West. Liu references not only the history of the Chinese laborers who built the railroads to support the West Coast Gold Rush, but also the hope shared among these migrant workers that they could find material prosperity in the new world. The Mills College Art Museum is excited to be the first venue outside of China to present Tai Cang— Great Granary. -

Ceramic's Influence on Chinese Bronze Development

Ceramic’s Influence on Chinese Bronze Development Behzad Bavarian and Lisa Reiner Dept. of MSEM College of Engineering and Computer Science September 2007 Photos on cover page Jue from late Shang period decorated with Painted clay gang with bird, fish and axe whorl and thunder patterns and taotie design from the Neolithic Yangshao creatures, H: 20.3 cm [34]. culture, H: 47 cm [14]. Flat-based jue from early Shang culture Pou vessel from late Shang period decorated decorated with taotie beasts. This vessel with taotie creatures and thunder patterns, H: is characteristic of the Erligang period, 24.5 cm [34]. H: 14 cm [34]. ii Table of Contents Abstract Approximate timeline 1 Introduction 2 Map of Chinese Provinces 3 Neolithic culture 4 Bronze Development 10 Clay Mold Production at Houma Foundry 15 Coins 16 Mining and Smelting at Tonglushan 18 China’s First Emperor 19 Conclusion 21 References 22 iii The transition from the Neolithic pottery making to the emergence of metalworking around 2000 BC held significant importance for the Chinese metal workers. Chinese techniques sharply contrasted with the Middle Eastern and European bronze development that relied on annealing, cold working and hammering. The bronze alloys were difficult to shape by hammering due to the alloy combination of the natural ores found in China. Furthermore, China had an abundance of clay and loess materials and the Chinese had spent the Neolithic period working with and mastering clay, to the point that it has been said that bronze casting was made possible only because the bronze makers had access to superior ceramic technology. -

Piece Mold, Lost Wax & Composite Casting Techniques of The

Piece Mold, Lost Wax & Composite Casting Techniques of the Chinese Bronze Age Behzad Bavarian and Lisa Reiner Dept. of MSEM College of Engineering and Computer Science September 2006 Table of Contents Abstract Approximate timeline 1 Introduction 2 Bronze Transition from Clay 4 Elemental Analysis of Bronze Alloys 4 Melting Temperature 7 Casting Methods 8 Casting Molds 14 Casting Flaws 21 Lost Wax Method 25 Sanxingdui 28 Environmental Effects on Surface Appearance 32 Conclusion 35 References 36 China can claim a history rich in over 5,000 years of artistic, philosophical and political advancement. As well, it is birthplace to one of the world's oldest and most complex civilizations. By 1100 BC, a high level of artistic and technical skill in bronze casting had been achieved by the Chinese. Bronze artifacts initially were copies of clay objects, but soon evolved into shapes invoking bronze material characteristics. Essentially, the bronze alloys represented in the copper-tin-lead ternary diagram are not easily hot or cold worked and are difficult to shape by hammering, the most common techniques used by the ancient Europeans and Middle Easterners. This did not deter the Chinese, however, for they had demonstrated technical proficiency with hard, thin walled ceramics by the end of the Neolithic period and were able to use these skills to develop a most unusual casting method called the piece mold process. Advances in ceramic technology played an influential role in the progress of Chinese bronze casting where the piece mold process was more of a technological extension than a distinct innovation. Certainly, the long and specialized experience in handling clay was required to form the delicate inscriptions, to properly fit the molds together and to prevent them from cracking during the pour. -

View the Herbs We Stock, Many Of

BASTYR CENTER FOR NATURAL HEALTH Chinese and Ayurvedic Herbal Dispensary Ayurvedic Herb List Retail price Retail price Ayurvedic Herb Name Ayurvedic Herb Name per gram per gram Amalaki $0.15 Tagar/Valerian $0.15 Arjuna $0.15 Talisadi $0.30 Ashoka $0.15 Trikatu $0.15 Ashwagandha $0.15 Triphala $0.15 Avipattikar $0.15 Triphala Guggulu $0.50 Bacopa $0.15 Tulsi $0.15 Bala $0.15 Vacha $0.15 Bibhitaki $0.15 Vidanga $0.15 Bilva $0.15 Vidari Kanda $0.15 Brahmi/Gotu Kola $0.15 Yashtimadhu/Licorice root $0.15 Bhumyamalaki $0.15 Yogaraj Guggulu $0.50 Calamus Root $0.15 Chandana/Red Sandalwood $0.30 Chitrak $0.15 Dashamula $0.15 Gokshura $0.15 Guduchi $0.15 Haridra/Turmeric $0.15 Haritaki $0.15 Hingvastak Churna $0.15 Kaishore Guggulu $0.50 Kalmegh $0.15 Kapikacchu $0.15 Kumari $0.15 Kutaja $0.15 Kutki $0.30 Manjishtha $0.15 Musta $0.15 Neem $0.15 Pippali $0.15 Punarnava $0.15 Punarnava Guggulu $0.50 Sat isapgul $0.15 Shankpushpi $0.15 Shardunika $0.15 Shatavari $0.15 Shilajit $0.50 Shunti/Ginger Root $0.15 Sitopaladi $0.30 Prices subject to change without notice Updated: 10/2018 BASTYR CENTER FOR NATURAL HEALTH Chinese and Ayurvedic Herbal Dispensary Chinese Raw Herb List Retail price Retail price Chinese Raw Herb Name Chinese Raw Herb Name per gram per gram Ai Ye $0.05 Cao Guo $0.10 Ba Ji Tian $0.10 Cao Wu (Zhi) $0.05 Ba Yue Zha $0.05 Ce Bai Ye $0.05 Bai Bian Dou $0.05 Chai Hu $0.15 Bai Bu $0.05 Chan Tui $0.25 Bai Dou Kou $0.10 Che Qian Zi $0.05 Bai Fu Zi (Zhi) $0.10 Chen Pi $0.05 Bai Guo (Granule) $0.27 Chi Shao Yao $0.10 Bai He $0.10 Chi Shi -

Major Vessel Types by Use

Major Vessel Types by Use Vessel Use Food Wine Water xian you you Vessel Type ding fang ding li or yan gui yu dou fu jue jia he gu zun lei hu (type 1) (type 2) fang yi pan Development Stage Pottery Prototype Early Shang (approx 1600–1400 BCE) Late Shang (approx 1400–1050 BCE) Western Zhou (approx 1050–771 BCE) Eastern Zhou (approx 770–256 BCE) PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE FROM THE GALLERY Shang Ceremony What was a ceremony at the Shang court like? thrust, now into a matching hollow on the left side David Keightley in his Sources of Shang History of the shell: ‘It is due to Father Jia.’ More time provides a wonderful description of what such passes . another crack forms in response. Moving a ceremony might have entailed. to the next plastron, Chue repeats the charges: ‘It is not due to Father Jia.’ Puk. ‘It is due to Father Jia.’ “Filtering through the portal of the ancestral temple, He rams the brand into the hollows and cracks the the sunlight wakens the eyes of the monster mask, second turtle shell, then the third, then the fourth. bulging with life on the garish bronze tripod. At the center of the temple stands the king, at the center “The diviners consult. The congregation of kinsmen of the four quarters, the center of the Shang world. strains to catch their words, for the curse of a dead Ripening millet glimpsed though the doorway father may, in the king’s eyes, be the work of a Shang-dynasty ritual wine vessel (he), Shang-dynasty ritual wine vessel (jue), shows his harvest rituals have found favor. -

From the Yellow Springs to the Land of Immortality

Schmucker Art Catalogs Schmucker Art Gallery Spring 2021 From the Yellow Springs to the Land of Immortality Sam Arkin Gettysburg College Georgia E. Benz Gettysburg College Allie N. Beronilla Gettysburg College Hailey L. Dedrick Gettysburg College Sophia Gravenstein Gettysburg College FSeeollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /cupola.gettysburg.edu/artcatalogs Part of the Art and Design Commons, Asian Art and Architecture Commons, and the Chinese Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Arkin, Sam; Benz, Georgia E.; Beronilla, Allie N.; Dedrick, Hailey L.; Gravenstein, Sophia; Gubernick, Alyssa G.; Hobbs, Elizabeth C.; Johnson, Jennifer R.; Lashendock, Emily; Morgan, Georgia P.; Oross, Amanda J.; Sullivan, Deirdre; Sullivan, Margaret G.; Turner, Hannah C.; Winick, Lyndsey J.; and Sun, Yan, "From the Yellow Springs to the Land of Immortality" (2021). Schmucker Art Catalogs. 36. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/artcatalogs/36 This open access art catalog is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From the Yellow Springs to the Land of Immortality Description The Yellow Springs is a vivid metaphorical reference to the final destination of a mortal being and the dwelling place of a departed one in ancient China. In the writings of philosophers, historians, and poets during the long period of Chinese history, the Yellow Springs is not only considered as an underground physical locus where a grave is situated, but also an emotionally charged space invoke grieving, longing, and memory for the departed loved ones.The subterranean dwelling at the Yellow Springs is both a destination for a departed mortal being and an intermediary place to an ideal and imaginative realm, the land of immortality where the soul would enjoy eternity. -

Power Animals and Symbols of Political Authority in Ancient Chinese Jades and Bronzes

Securing the Harmony between the High and the Low: Power Animals and Symbols of Political Authority in Ancient Chinese Jades and Bronzes RUI OLIVEIRA LOPES introduction One of the issues that has given rise to lengthy discussions among art historians is that of the iconographic significance of Chinese Neolithic jade objects and the symbolic value the decorations on bronze vessels might have had during the Shang (c. 1600 –1045 b.c.) and Zhou (1045–256 b.c.) dynasties. Some historians propose that the representations of real and imaginary animals that often decorated bronze vessels bore no specific meaning. The basis of their argument is that there is no reference to them among the oracle bones of the Shang dynasty or any other contem- poraneous written source.1 They therefore suggest that these were simply decorative elements that had undergone a renovation of style in line with an updating of past ornamental designs, or through stylistic influence resulting from contact with other peoples from western and southern China ( Bagley 1993; Loehr 1953). Others, basing their arguments on the Chinese Classics and other documents of the Eastern Zhou and Han periods, perceive in the jades and bronzes representations of celestial beings who played key roles in communicating with ancestral spirits (Allan 1991, 1993; Chang 1981; Kesner 1991). The transfer of knowledge that determined the continuity of funerary practices, ritual procedures, artistic techniques, and the transmission of the meanings of iconographic representations was certainly subject to some change, but would have been kept in the collective memory and passed on from generation to generation until it was recorded in the most important documents regarding the insti- tutions of Chinese culture. -

English Language, Large Print

ENGLISH LANGUAGE, LARGE PRINT Ancient Bells RESOUND of China Resound: Ancient Bells of China Bells were among the first metal objects created in China. Beginning over 3,500 years ago, small, primitive noisemakers grew into gongs and further evolved into sets of hand bells for playing melodies. Centuries of technological experimentation later resulted in sophisticated bells that produced two pitches when struck at different spots. Variations in size, shape, decoration, and sound also reveal regional differences across north and south China. By the late Bronze Age large sets of tuned bells were played in ensemble performances in both areas. Cast from bronze, these durable instruments preserve valuable hints about the character of early Chinese music. Today we can use technology to explore these ancient bells and to explain their acoustical properties, but we know little about the actual sound of this early music. To bring the bells to life, we commissioned three composers to create soundscapes using the recorded tones of a 2,500‐ year‐old bell set on display. Each of them also produced a video projection to interpret his composition with moving images that allow us to "see sound." Unless otherwise indicated, all of these objects are from China, are made of bronze, and were the gift of the Dr. Paul Singer Collection of Chinese Art of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; a joint gift of the Arthur M. Sackler Foundation, Paul Singer, the AMS Foundation for the Arts, Sciences, and Humanities, and the Children of Arthur M. Sackler. 2 Symbols of Refinement Chinese regional courts competed with one another on the battlefield and on the music stage. -

2000–01 Excavation of the Shang Bronze Foundry Site at Xiaomintun Southeast in Anyang

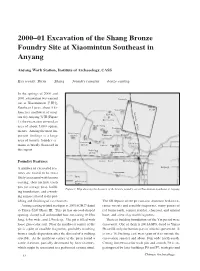

2000–01 Excavation of the Shang Bronze Foundry Site at Xiaomintun Southeast in Anyang Anyang Work Station, Institute of Archaeology, CASS Key words: Yinxu Shang foundry remains bonze casting In the springs of 2000 and 2001, excavation was carried Tuwangdu out at Xiaomintun 孝民屯 Southeast Locus, about 5 ki- Sanjiazhuang Shilipu Huan lometers northwest of mod- Jing-guang Railway Xiaoying ern city Anyang 安阳 (Figure Qianxiaoying 1); the excavation covered an area of about 5,000 square Houjiazhuang Xiaosikong meters. Among the most im- Beixinzhuang portant findings is a large (moved) Wuguancun Dasikong area of bronze foundry re- River Xiaomintun ▲ Yubei Cotton (moved) mains as briefly discussed in Sipanmo Xiaotun Factory this report. Baijiafen (moved) Huayuanzhuang Hougang Wangyukou Guojiawan Foundry Features Angang Road Gaolouzhuang A number of excavated fea- Anyang tures are found to be most Liujiazhuang likely associated with bronze Yinxu walled town at casting; they include trash Huanbei pits (or storage pits), build- Figure 1. Map showing the location of the bronze foundry site at Xiaomintun Southeast in Anyang ing foundations, and a work- ing surface related to the pol- ishing and finishing of cast bronzes. The fill deposit of the pit contains abundant broken ce- Among casting-related trash pits is 2001AGH27 dated ramic vessels and crucible fragments, many pieces of to Yinxu 殷墟 Phase III. This pit has an oval-shaped red burnt earth, copper residue, charcoal, and animal opening, slanted wall and rounded base, measuring 10.25m bone, and a few clay mold fragments. long, 6.4m wide, and 2.9m deep. The pit is filled with Thirteen building foundations of the Yin period were loose gray-color soil. -

The Prehistory of Chinese Music Theory

ELSLEY ZEITLYN LECTURE ON CHINESE ARCHAEOLOGY AND CULTURE The Prehistory of Chinese Music Theory ROBERT BAGLEY Princeton University The division of the octave into twelve semitones and the transposition of scales have also been discovered by this intelligent and skillful nation. But the melodies transcribed by travellers mostly belong to the scale of five notes. Helmholtz, On the Sensations of Tone (1863)1 THE EARLIEST TEXTS ABOUT MUSIC THEORY presently known from China are inscriptions on musical instruments found in the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng, the ruler of a small state in the middle Yangzi region, who died in 433 BC. Excavated in 1978, the tomb was an underground palace of sorts, a timber structure furnished with an astonishing array of lordly posses- sions (Fig. 1).2 In two of its four chambers the instruments of two distinct musical ensembles were found. Beside the marquis’s coffin in the east chamber was a small ensemble for informal entertainments, music for the royal bedchamber perhaps, consisting of two mouth organs, seven zithers, and a small drum. In the central chamber, shown under excavation in Figure 2, a much larger ensemble for banquets and rituals was found. Composed of winds, strings, drums, a set of chime stones, and a set of bells, it required more than twenty performers. The inscriptions about music theory appear on the chime stones and the bells. They concern Read at the Academy on 26 October 2004. 1 Quoted from Alexander Ellis’s 1885 translation (p. 258) of the fourth German edition (1877). 2 The excavation report, in Chinese, is Zeng Hou Yi mu (1989). -

Big Ding 鼎 and China Power: Divine Authority and Legitimacy

Big Ding 鼎 and China Power: Divine Authority and Legitimacy ELIZABETH CHILDS-JOHNSON By the eastern zhou and imperial eras of Chinese history, a legend had grown cel- ebrating the ding 鼎 bronze vessel as the preeminent symbol of state authority and divine power. The mythic theme of “The First Emperor’s [Qin Shi Huangdi’s] Search for the Zhou Ding” or “The First Qin Emperor’s Failure to Discover the Ding” deco- rate the main gables of more than several Eastern Han funerary shrines, including Xiaotangshan and Wuliang in Shandong province (Wu 1989 : 138, 348). Pre-Han records in the Zuozhuan: 7th year of Duke Zhao (左传: 昭公七年) as well as the “Geng- zhu” chapter in the Mozi (墨子: 耕柱篇) record the significance of this mythic representation. The Mozi passage states: In ancient times, King Qi of the Xia [Xia Qi Wang] commissioned Feilian to dig minerals in mountains and rivers and to use clay molds, casting the ding at Kunwu. He ordered Wengnanyi to divine with the help of the tortoise from Bairuo, saying: “Let the ding, when completed, have a square body and four legs. Let them be able to boil without kindling, to hide themselves without being lifted, and to move themselves without being carried so that they will be used for sacrifice at Kunwu.” Yi interpreted the oracle as saying: “The offering has been accepted. When the nine ding have been completed, they will be ‘transferred’ down to three kingdoms. When Xia loses them, people of the Yin will possess them, and when people of the Yin lose them, people of the Zhou will pos- sess them.”1 [italics added] As maintained in this article, the inspiration for this popular legend of mythic power most likely originated during dynastic Shang times with the first casting in bronze of the monumental, four-legged ding.