Real Teaching and Real Learning Vs Narrative Myths About Education Marshall W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premiere Props • Hollyw Ood a Uction Extra Vaganza VII • Sep Tember 1 5

Premiere Props • Hollywood Auction Extravaganza VII • September 15-16, 2012 • Hollywood Live Auctions Welcome to the Hollywood Live Auction Extravaganza weekend. We have assembled a vast collection of incredible movie props and costumes from Hollywood classics to contemporary favorites. From an exclusive Elvis Presley museum collection featured at the Mississippi Music Hall Of Fame, an amazing Harry Potter prop collection featuring Harry Potter’s training broom and Golden Snitch, to a entire Michael Jackson collection featuring his stage worn black shoes, fedoras and personally signed items. Plus costumes and props from Back To The Future, a life size custom Robby The Robot, Jim Carrey’s iconic mask from The Mask, plus hundreds of the most detailed props and costumes from the Underworld franchise! We are very excited to bring you over 1,000 items of some of the most rare and valuable memorabilia to add to your collection. Be sure to see the original WOPR computer from MGM’s War Games, a collection of Star Wars life size figures from Lucas Film and Master Replicas and custom designed costumes from Bette Midler, Kate Winslet, Lily Tomlin, and Billy Joel. If you are new to our live auction events and would like to participate, please register online at HollywoodLiveAuctions.com to watch and bid live. If you would prefer to be a phone bidder and be assisted by one of our staff members, please call us to register at (866) 761-7767. We hope you enjoy the Hollywood Live Auction Extravaganza V II live event and we look forward to seeing you on October 13-14 for Fangoria’s Annual Horror Movie Prop Live Auction. -

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

17 December 2003

Screen Talent Agency 818 206 0144 JUDY GELLMAN Costume Designer judithgellman.wordpress.com Costume Designers Guild, locals 892 & 873 Judy Gellman is a rarity among designers. With a Midwest background and training at the University of Wisconsin and The Fashion Institute of Technology (NYC) Judy began her career designing for the Fashion Industry before joining the Entertainment business. She’s a hands-on Designer, totally knowledgeable in pattern making, construction, color theory, as well as history and drawing. Her career has taken her from Chicago to Toronto, London, Vancouver and Los Angeles designing period, contemporary and futuristic styles for Men, Women, and even Dogs! Gellman works in collaboration with directors to instill a sense of trust between her and the actors as they create the characters together. This is just one of the many reasons they turn to Judy repeatedly. Based in Los Angeles, with USA and Canadian passports she is available to work worldwide. selected credits as costume designer production cast director/producer/company/network television AMERICAN WOMAN Alicia Silverstone, Mena Suvari (pilot, season 1) various / John Riggi, John Wells, Jinny Howe / Paramount TV PROBLEM CHILD Matthew Lillard, Erinn Hayes (pilot) Andrew Fleming / Rachel Kaplan, Liz Newman / NBC BAD JUDGE Kate Walsh, Ryan Hansen (season 1) various / Will Farrell, Adam McKay, Joanne Toll / NBC SUPER FUN NIGHT Rebel Wilson (season 1) various / Conan O’Brien, John Riggi, Steve Burgess / ABC SONS OF TUCSON Tyler Labine (pilot & series) Todd Holland, -

MIPCOM Buyers Facing a Glut of New U.S. Shows

MIPCOM 2015 DAY 2 ™ October 6, 2015 My 2 Cents: The rivalry MIPCOM Buyers Facing a MIPJr Vs. BLE between New York City Glut of New U.S. Shows Is A Matter and Los Angeles Page 22 he new U.S. TV season features Of Opinion 120 scripted shows, if one considers broadcast, cable INSIDE: T or those in the kids business, and OTT services. Of these, over Cannes Visuals — 70 new series are on commercial this is a key time of the year. networks. That doesn’t even include FMIPJunior, the market for MIPCOM Photo Report the summer entries and mid-season kids’ audiovisual content that was shows, despite the fact that the U.S. held on Saturday and Sunday here Page 21 studios prefer talking about them in Cannes, is immediately followed at NATPE in January. At least six of by London’s Brand Licensing Europe the new shows are based on movies, which, by any yardstick, is Europe’s COMING UP: and even more are expected the next pre-eminent licensing show. So, the Focus on Latin season. In addition, this season sees question is — who goes to which a record number of movie super stars and why? American Television migrating to television. buyers will be able to shop over 4,000 The answer, possibly unsur- As reported in VideoAge’s MIPCOM new shows, but the industry will prisingly, is, it depends on who October 7 Issue, more than 400 new scripted not return to the “pick-and choose” you are, what you want, and your series will ultimately be introduced system of the early years of television, focus. -

LEADING LADIES GALA Commemorative Book

Cover 1 WELCOME TO THE LEADING LADIES GALA Bryn Mawr Film Institute Greetings all – Board of Directors Past & Present Tonight, we celebrate Juliet Goodfriend, a Renaissance person in the truest sense of the word: a lover of the arts, an astute Rev. Eugene Bay Charlie Bloom businessperson, a community leader, and a leader amongst Sabina Bokhari her peers. I mention peers because Juliet’s leadership is David Brind recognized within the ranks of the Art House Convergence Anmiryam Budner* (AHC), a national organization devoted to community-based, Alice Bullitt* mission-driven theaters like BMFI. Through the years, the AHC Elizabeth H. Gemmill has recognized Juliet for establishing and running one of the Juliet J. Goodfriend* Doris Greenblatt most successful member-supported motion picture theater Harry Groome* and film education centers in the country. Not only has Juliet Joanne Harmelin* moved BMFI forward, she has moved the entire art house John H. Hersker* movement forward. Tigre Hill* Francie Ingersoll* Working closely with Juliet over the last 12 years has Sandra Kenton allowed me to participate in a truly phenomenal process. Sir Ben Kingsley † She saw a need in our community for thoughtful films to be Paul Kistler presented, enjoyed, and studied, in a beautiful, state-of-the- Sidney Lazard art environment, with friends and family. Though a very small Daylin Leach ‡ Francis J. Leto* component of the film industry as a whole, so-called ‘art films’ Lonnie Levin are the lifeblood of Bryn Mawr Film Institute and continue to Stephanie Naidoff be a vital part of world cinema. Juliet has ensured that the Amy Nislow best of these films—the ones people end up talking about—are Robert Osborne† exhibited for BMFI audiences. -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

6769 Shary & Smith.Indd

ReFocus: The Films of John Hughes 66769_Shary769_Shary & SSmith.inddmith.indd i 110/03/210/03/21 111:501:50 AAMM ReFocus: The American Directors Series Series Editors: Robert Singer, Frances Smith, and Gary D. Rhodes Editorial Board: Kelly Basilio, Donna Campbell, Claire Perkins, Christopher Sharrett, and Yannis Tzioumakis ReFocus is a series of contemporary methodological and theoretical approaches to the interdisciplinary analyses and interpretations of neglected American directors, from the once-famous to the ignored, in direct relationship to American culture—its myths, values, and historical precepts. The series ignores no director who created a historical space—either in or out of the studio system—beginning from the origins of American cinema and up to the present. These directors produced film titles that appear in university film history and genre courses across international boundaries, and their work is often seen on television or available to download or purchase, but each suffers from a form of “canon envy”; directors such as these, among other important figures in the general history of American cinema, are underrepresent ed in the critical dialogue, yet each has created American narratives, works of film art, that warrant attention. ReFocus brings these American film directors to a new audience of scholars and general readers of both American and Film Studies. Titles in the series include: ReFocus: The Films of Preston Sturges Edited by Jeff Jaeckle and Sarah Kozloff ReFocus: The Films of Delmer Daves Edited by Matthew Carter and Andrew Nelson ReFocus: The Films of Amy Heckerling Edited by Frances Smith and Timothy Shary ReFocus: The Films of Budd Boetticher Edited by Gary D. -

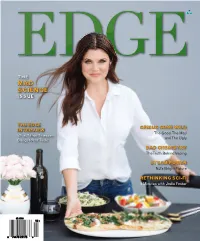

The Mad Science Issue

THE MAD SCIENCE ISSUE THE EDGE GENIUS GONE WILD INTERVIEW The Good, The Mad What Tiffani Thiessen and The Ugly Brings to the Table BAD CHEMISTRY The Truth Behind Vaping STEAM POWER NJ’s Bright Future RETHINKING SCI-FI 5 Minutes with Jodie Foster $3.95US 10 0 74470 25173 6 2 Looking for a The Mad Science Issue PUBLISHERS Jeweler? doug harris, graNt kNaggs ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Jeffrey shaNes EDITORIAL MANAGING EDITOR mark stewart EDITORS christiNe gibbs, doug harris, yolaNda NaVarra flemiNg EDITOR AT LARGE ashleigh oweNs FOOD EDITOR mike coheN ASSIGNMENTS EDITOR Zack burgess ENTERTAINMENT EDITOR rachel stewart ART DESIGN DIRECTOR Jama bowmaN SALES 908.994.5138 VP BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Jeffrey shaNes SENIOR MEDIA MARKETING SPECIALIST christiNe layNg WEB WEB DESIGN aNdrew J. talcott / ok7, llc ONLINE MANAGER JohN maZurkiewicZ TRINITAS REGIONAL MEDICAL CENTER CHAIRPERSON sr. rosemary moyNihaN, sc Outstanding, PRESIDENT & CEO gary s. horaN, fache LETTERS TO THE EDITOR edge c/o trinitas regional medical center Service, Public relations department 225 williamson street | elizabeth, New Jersey 07202 [email protected] Selection, VISIT US ON THE WEB www.edgemagonline.com this is Volume 10, issue 4. edge magazine is published 5 times a year in february, april, June, september and November. this material is designed for information purposes only. None of Price the information provided in healthy edge constitutes, directly or indirectly, the practice of medicine, the dispensing of medical services, a professional diagnosis or a treatment plan. the information in healthy edge should not be considered complete nor should it be relied on to suggest a course of treatment for a particular individual. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Wigfield the Can-Do Town

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Wigfield The Can-Do Town That Just May Not by Amy Sedaris Wigfield: The Can-Do Town That Just May Not by Amy Sedaris, Paul Dinello, Stephen Colbert. I think people’s first impression of Wigfield is that it is just a chain of porno shops, strip clubs, and used auto parts yards. Well, it’s a lot more than that. It’s Pornographers and Strippers and People Who Sell Used Auto parts. Cinnamon (Stripper and Resident of Wigfield), Wigfield: The Can- Do Town That Just May Not. If Amy Sedaris is better known as the sister of public radio superstar David, it’s her own fault. For someone so fabulously talented, she is also remarkably anonymous. It’s likely you’ve seen her — not so likely you knew who she was. She’s done theatre (off-broadway, limited run, forget about a ticket) and a critically acclaimed TV stint ( Strangers With Candy ). She flits in and out of the big screen ( Maid in Manhattan ) and small (Finch’s lookalike girlfriend in “Just Shoot Me”) and if you live in New York, you might have eaten one of her muffins. Yes, muffins. It’s a constant in her bios and not just an attention-getting celebrity trick. She bakes and sells muffins — for $1 a piece. A friend of mine used her for a bridal shower she was hosting — two dozen muffins, $24 bucks — and in a story twist that can only happen in Manhattan, Sedaris apologetically warned she’d had to borrow Sarah Jessica Parker’s oven last-minute when hers blinked out. -

FRED MURPHY, ASC Director of Photography

FRED MURPHY, ASC Director of Photography Selected credits: LIKE FATHER (Splinter Unit) - Netflix - Lauren Miller Rogen, director GHOST TOWN - DreamWorks - David Koepp, director ANAMORPH - IFC Films - Henry Miller, director DRILLBIT TAYLOR - Paramount - Steve Brill, director RV - Columbia - Barry Sonnenfeld, director DREAMER - DreamWorks - John Gatins, director SECRET WINDOW - Columbia - David Koepp, director FREDDY VS. JASON - New Line - Ronny Yu, director AUTO FOCUS - Columbia - Paul Schrader, director MOTHMAN PROPHECIES - Lakeshore - Mark Pellington, director WITNESS PROTECTION - HBO - Richard Pearce, director STIR OF ECHOES - Artisan - David Koepp, director OCTOBER SKY - Universal - Joe Johnston, director METRO - Caravan - Thomas Carter, director THE FANTASTICKS - MGM - Michael Ritchie, director FAITHFUL - Savoy Pictures - Paul Mazursky, director MURDER IN THE FIRST - Three Marks Productions - Marc Rocco, director THE PICKLE - Columbia - Paul Mazursky, director JACK THE BEAR - 20th Century Fox - Marshall Herskovitz, director ENEMIES: A LOVE STORY - 20th Century Fox - Paul Mazursky, director FRESH HORSES - Weintraub - Davis Anspaugh, director FULL MOON IN BLUE WATER - Trans World Entertainment - Peter Masterson, director FIVE CORNERS - Cineplex Odeon - Tony Bill, director BEST SELLER - Orion - John Flynn, director THE DEAD - Vestron - John Huston, director HOOSIERS - Orion - David Anspaugh, director EDDIE AND THE CRUISERS - Embassy Pictures - Martin Davidson, director THE STATE OF THINGS (co-DP) - Gracy City - Wim Wenders, director -

Barbara Hershey

BARBARA HERSHEY Films: Insidious: The Last Key Lorraine Lambert Adam Robitel Blumhouse Productions The 9th life of Louis Drax Violet Drax Alexandre Aja Brightlight Pictures Sister Susan Presser David Lascher Showtime Networks Answers to Nothing Marilyn Matthew Leutwyler Ambush Entertainment Insidious Lorraine Lambert James Wan Film District Black Swan* Erica Darren Aronofsky Fox Searchlight Answers To Nothing Marilyn Matthew Leutwyler Independent Albert Schweitzer Helen Schweitzer Two Ocenans Production Gavin Millar Uncross The Stars Hilda Ken Goldie Independent The Bird Can’t Fly Melody Threes Anna Independent Childless Natalie Charlie Levi Independent Love Comes Lately Rosalie Jan Schutte Independent Riding The Bullet Jean Parker Mick Garris M P C A 11:14 Norma Greg Marcks Independent Lantana Dr Valerie Somers Ray Lawrence Independent Passion Rose Grainger Peter Duncan Independent A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries Marcella Willis James Ivory October Films Frogs For Snakes Eva Santana Amos Poe Shooting Gallery The Portrait Of A Lady** Madame Serena Merle Jane Campion Polygram Films The Pallbearer Ruth Abernathy Matthew Reeves Miramax Last Of The Dogmen Prof. Lilian Sloan Tab Murphy Savoy A Dangerous Woman Frances Beecham Rowland V. Lee Universal Pictures Swing Kids Frau Muller Thomas Carter Buena Vista Falling Down Elizabeth Travino Joel Schumacher Warner Bros Splitting Heirs Duchess Lucinda Robert Young Universal Public Eye Kay Levitz Howard Franklin Universal Defenseless Thelma ' T.k.' Martin Campbell New Line Tune In Tomorrow Aunt Julia Jon Amiel Cinecom Paris Trout *** Hanna Trout Stephen Gyllenhaal Showtime Last Temptation Of Christ**** Mary Magdalene Martin Scorsese Universal Beaches Hillary Whitney Essex Gary Marshall Walt Disney Prd. A World Apart Diana Roth Chris Menges Working Title Ltd Hoosiers Myra Fleener David Anspaugh Hemdale Film Corp Hannah And Her Sisters***** Lee Woody Allen Orion Pictures Corp Tin Men Nora Tilley Barry Levinson Walt Disney Prd Shy People****** Ruth A.