Gay, Lesbian & Bisexual People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domestic Violence and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Relationships

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER RELATIONSHIPS WHY IT MATTERS Domestic violence is defined as a pattern of behaviors utilized by one partner (the batterer or abuser) to exert and maintain control over another person (the survivor or victim) where there exists an intimate and/or dependent relationship. Experts believe that domestic violence occurs in the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community with the same amount of frequency and severity as in the heterosexual community. Society’s long history of entrenched racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia prevents LGBT victims of domestic violence from seeking help from the police, legal and court systems for fear of discrimination or bias.1 DID YOU KNOW? • In ten cities and two states alone, there were 3,524 incidents of domestic violence affecting LGBT individuals, according to the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs 2006 Report on Lesbian, Gay, Bi-Sexual and Transgender Domestic Violence.1 • LGBT domestic violence is vastly underreported, unacknowledged, and often reported as Intimidation something other than domestic violence.1 Coercion and Threats Making you afraid, Threatening to harm you, abusing pets, • Delaware, Montana and South Carolina explicitly family or friends, or him/ displaying weapons, herself, threatening to using tactics to exclude same-sex survivors of domestic violence out you. reinforce homophobic from protection under criminal laws. Eighteen control states have domestic violence laws that are Economic Abuse Emotional Abuse Preventing you from working, Putting you down, verbal gender neutral but apply to household members controlling all assets, interfering abuse, playing mind games, 2 with education, requiring you to humiliating you, reinforcing only. -

I Think I Might Be Bisexual “Don’T Let Society Tell You Or Categorize You As Confused Or Greedy Because of Who You Are

I Think I Might Be Bisexual “Don’t let society tell you or categorize you as confused or greedy because of who you are. We are not confused and we know exactly what we want. Being bisexual or pansexual does not make us different — and that goes for all LGBT+ people.” - Lisa, 23 Sex - when you’re born, the What Does It Mean to Be Bisexual? doctor decides if you are male or female based on if you have Generally speaking, someone who is bisexual is able to be attracted to and have a penis or vagina intimate relationships with people of multiple genders. A bisexual woman, for Gender - What defines example, may have sex with, date or marry another woman, a man or someone who someone as feminine or is non-binary. A bisexual person may have a preference of one gender over another, masculine, including how people expect you to behave or develop a preference over time. Sexuality doesn’t change based on relationship as well as how you feel and status — if a bisexual man is dating, having sex with or married to a woman, he is identify still bisexual; he isn’t straight because he is with a woman. Some bisexual people Sexual orientation - to whom may use different language to describe themselves, such as ‘pansexual’, ‘queer’ or you are sexually attracted. ‘gay.’ Some individuals prefer the term pansexual (‘pan’ means many) because it may Sexual orientation isn’t dictated by sex or gender; feel more inclusive of those who are genderqueer or don’t identify as male or female. -

Negotiations Around Power, Resources, and Tasks Within Lesbian Relationships

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Doctorate in Social Work (DSW) Dissertations School of Social Policy and Practice Spring 5-20-2019 Negotiations Around Power, Resources, and Tasks Within Lesbian Relationships: Does This Process Affect the Perception of Intimacy and Sexual Satisfaction? Sarah Bohannon University of Pennslyvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2 Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Bohannon, Sarah, "Negotiations Around Power, Resources, and Tasks Within Lesbian Relationships: Does This Process Affect the Perception of Intimacy and Sexual Satisfaction?" (2019). Doctorate in Social Work (DSW) Dissertations. 137. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2/137 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2/137 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Negotiations Around Power, Resources, and Tasks Within Lesbian Relationships: Does This Process Affect the Perception of Intimacy and Sexual Satisfaction? Abstract In an environment typically dominated by heteronormative values and behavior, the distribution of power, resources, and tasks within an intimate relationship often is gender-determined. How power, resources, and tasks are negotiated within a lesbian relationship and how this process may affect the perception of intimacy and sexual satisfaction remains a fertile area for exploration. Through the lens of relational-cultural theory and social exchange theory, this dissertation examines the literature that considers the ways in which power is negotiated and distributed in intimate relationships, with a specific mpe hasis on lesbian relationships. In addition, literature that considers the interplay between power and perceived intimacy and sexual satisfaction will be analyzed, again with an emphasis on lesbian relationships. -

LGB&T Ebulletin June 2018

LGB&T EBulletin June 2018 NEWS Don’t forget to follow our facebook page to keep up to date with events in between ebulletins https://www.facebook.com/LGBTUnisonNI/ UNISON LGBT Committee Although it is referred to as a committee, it is open to any LGBT member to attend. The next meeting is at 6.15 – 8pm on Wednesday 27th June in UNISON. At this meeting we have invited a representative from Genderjam to talk about trans issues (postponed from last scheduled night). So if you don’t know your non binary from your gender fluid or your transsexual from your transgender, come along. This will link into UNISON National’s consultation on the proposal to extend LGBT to LGBT+ to be more inclusive. There will also be a discussion on Pride activities. If you are coming along, please let me know for catering. Marriage Equality Rally We are still marching and campaigning for Marriage Equality. The latest rally earlier this month brought thousands onto the streets again in both Belfast and Derry and UNISON had a great presence. Thanks to all those who were able to come along it. You can support the Love Equality campaign financially by donating at https://marriageequalityni.causevox.com/ or you can buy a Love Equality tshirt at https://equalitee.co.uk/ There are photos of the Belfast rally at https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.1827374837285359.1073741852.138564629 499730&type=1&l=3a7bc348d9 And Derry via Kathryn Daily https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10215493672596154&set=pcb.102154936907 56608&type=3&theater A song of solidarity has been written and recorded and you can check it out at https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=FKIbhfTZhVY Celebrate the 70th Birthday of the NHS in Belfast at 2.30pm on Saturday 30th June https://www.ictuni.org/publications/nicictu-nhs-at-70-a3-poster Trade Unions are joining civic society to invite people onto the streets on Saturday 30th June to celebrate and show your support for the NHS and to defend its future. -

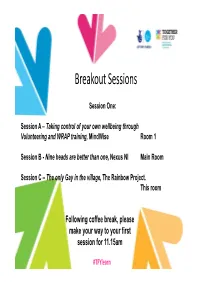

Breakout Sessions

Breakout Sessions Session One: Session A – Taking control of your own wellbeing through Volunteering and WRAP training, MindWise Room 1 Session B - Nine heads are better than one, Nexus NI Main Room Session C – The only Gay in the village, The Rainbow Project. This room Following coffee break, please make your way to your first session for 11.15am #TFYlearn Together for You – Targeting LGB&/T populations Together for You –Targeting The RainbowLGB&/T Project populations –Promoting the health and wellbeing of lesbian, gay, bisexualThe Rainbow and/or Projecttransgender –Promoting people and the healththeir families and wellbeing in Northern of lesbian, Ireland. gay, bisexual and/or transgender people and their families in Northern Ireland. Who are we? Ireland’s largest LGB&/T organisation –2 bases Established in 1994 Official change in September 2012 Charity Commission registered in 2014 Our Vision The Rainbow Project’s vision is of a society free from homophobia, heterosexism and transphobia where all people are recognised as equals. Who are we? Mission Statement The Rainbow Project aims to promote the health and wellbeing of lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or transgender people and their families in Northern Ireland, as well as those questioning their orientation or gender, through partnership, advocacy and the development and delivery of appropriate support services. Values Our role Sub –contracted partner –LGB&/T intervention • 4 Social and Peer Support groups in areas with limited/no LGB&/T social and peer support • 60 people beneficiaries -

Gay and Bisexual Health Care

Get the Facts... LGBT VETERAN HEALTH CARE Male Veterans: Gay and Bisexual Health Care Gay and bisexual Veterans face increased health risks and unique challenges in accessing quality health care. There are an estimated 1 million lesbian, gay, and bisexual Veterans in the United States. Many of these Veterans may receive care at the VHA. We are working to be a national leader in health care for LGBT Veterans and assure that high-quality care is provided in a sensitive, respectful environment at VHAs nationwide. The following is a list of the top things gay and bisexual male Veterans should discuss at their VHA visits. 1. COME OUT TO YOUR HEALTH CARE PROVIDER 3. SUBSTANCE USE/ALCOHOL In order to provide you with the best care possible, your Heavy drinking and substance use are common among VHA doctor should know you are gay or bisexual. It should gay and bisexual men. Alcohol and drug misuse can lead to prompt him/her to ask specific questions about you and serious health, relationship, employment, and legal problems. offer appropriate health screens. If your provider does not Problems with drinking or drug use may occur in response to seem comfortable with you as a gay or bisexual man, ask stress, and/or in combination with PTSD, depression, or other for another VHA provider. Coming out to your providers is medical conditions. Fortunately, there are proven methods to an important step to being healthy. For frequently asked help Veterans recover from alcohol or drug misuse, including questions about privacy, see Your Privacy Matters on page 3. -

It's a Beautiful Day in the Gayborhood

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses Spring 2011 It’s a Beautiful Day in the Gayborhood Cori E. Walter Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies Commons Recommended Citation Walter, Cori E., "It’s a Beautiful Day in the Gayborhood" (2011). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 6. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/6 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. It’s a Beautiful Day in the Gayborhood A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Cori E. Walter May, 2011 Mentor: Dr. Claire Strom Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida 2 Table of Contents________________________________________________________ Introduction Part One: The History of the Gayborhood The Gay Ghetto, 1890 – 1900s The Gay Village, 1910s – 1930s Gay Community and Districts Go Underground, 1940s – 1950s The Gay Neighborhood, 1960s – 1980s Conclusion Part Two: A Short History of the City Urban Revitalization and Gentrification Part Three: Orlando’s Gay History Introduction to Thornton Park, The New Gayborhood Thornton Park, Pre-Revitalization Thornton Park, The Transition The Effects of Revitalization Conclusion 3 Introduction_____________________________________________________________ Mister Rogers' Neighborhood is the longest running children's program on PBS. -

LGBT Organisations in Northern Ireland

Lesbian, gay, bisexual & trans (LGBT) Organisation s in Northern Ireland Published by The Rainbow Project: Updated February 2009 PLEASE NOTE: This is an internal resource used by The Rainbow Project. The information provided on this list is for information purposes only. The Rainbow Project has taken all reasonable steps to ensure that the information contained on these pages is accurate and correct at the time of writing. Whilst every care has been taken in the compilation of this information The Rainbow Project will not be held responsible for any loss, damage or inconvenience caused as a result of any inaccuracy or error within these pages. The inclusion of any company/society/group/person’s within these pages should not be used as a recommendation or endorsement of that company/society/group/person’s name, products and/or services. Service users and professionals are encouraged to thoroughly check out the credentials of each company/society/group/person before engaging with those services. COMMUNITY GROUPS/ORGANISATIONS Causeway LGBT Network c/o Simon Community, 14 -16 Lodge Road, Coleraine, BT52 1NB Banbridge/Craigavon LGBT Group tel: 07910980314 tel: 07597 977849 web: www.causewaylgbt.co.uk/ web: www.bebo.com/BanbridgeCraigaL A social and support group for the LGBT community email: [email protected] or in Portrush, Portstewart, Coleraine, Ballycastle, [email protected] Support/social group for the LGBT community in the Ballymoney, Castlerock, Bushmills and Limavady . Banbridge & Craigavon areas. Changing Attitude Ireland web: www.changingattitudeireland.org Belfast Butterfly Club A network of people, gay and straight, working for PO Box 210, Belfast, BT1 1BG tel: (028) 9267 3720 the full affirmation of LGBT persons within the web: www.belfastbutterflyclub.co.uk Church of Ireland. -

5 Myths About the Teaching of the Catholic Church on Homosexuality

5 Myths about the Teaching of the Catholic Church on Homosexuality Rev. Philip Smith (Parochial Vicar, Most Blessed Sacrament Church and Corpus Christi University Parish, Toledo, OH --- Diocese of Toledo) Myth: The Catholic Church encourages a negative attitude towards people who identify as homosexual. Catholic Church Teaching: The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that persons with homosexual tendencies “must be accepted with respect, compassion, and sensitivity. Every sign of unjust discrimination in their regard should be avoided” (CCC 2358). The Catholic Church continues Jesus’ mission in offering salvation to all people including those with same-sex attractions. The Catholic Church welcomes parishioners with same-sex attractions as God’s beloved sons and daughters and strives to share with them the joy of the Good News of God’s unconditional love. Myth: The Church condemns persons with same-sex attractions and believes that persons with same-sex attraction should just “pray the gay away”. Catholic Church Teaching: While the Catholic Church teaches that homosexual acts are morally unacceptable, the Church teaches that homosexual inclinations are not sinful in themselves. The Church recognizes that in a significant number of persons their homosexual desires are “deep- seated” and that these desires will accompany them throughout their life. The Catholic Church does not endorse an approach that requires all persons with same-sex attractions to become “straight” or heterosexual. The Catholic Church teaches that God calls all persons, including those with same-sex attractions, to live the virtue of chastity. For persons with same-sex attractions, living chastely includes not engaging in homosexual acts. -

Out on Your Own: an Examination of the Mental

Out on Your Own An Examination of the Mental Health of Young Same-Sex Attracted Men Helen McNamee ISBN: 0-9552781-0-4 978-0-9552781-0-5 First Published March 2006 Published by The Rainbow Project 2-8 Commercial Court Belfast BT1 2NB Tel: 028 9031 9030 Fax: 028 9031 9031 Email: [email protected] Web: www.rainbow-project.org Copyright © 2006 The Rainbow Project / Helen McNamee The Rainbow Project is a registered charity number NI30101 Acknowledgements This research would not have been possible without the contribution of the research participants. Thank you to all of those involved, including those who took part in the pilot of the questionnaire, those who completed the survey and those who gave up their time to take part in the interviews. The author would also like to thank the research steering group, Karen Beattie, Dominic McCanny, Katy Radford, Neil Jarman and Dermot Feenan. Particular thanks to Dirk Schubotz for his help with the statistical analysis. The guidance and advice provided throughout the completion of the report was hugely appreciated. In addition, the author would like to thank The Rainbow Project staff for their support on all aspects of the research. Special thanks to Gary McKeever who edited the final report. Finally, the author and The Rainbow Project would like to thank The Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund for funding the research. Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 1. Introduction 9 2. Literature review: Mental health and young same-sex attracted men 11 3. Methodology 23 4. Findings of survey and face-to-face interviews 27 4.1 Introduction and profile of respondents and interviewees 27 4.2 Mental health 30 4.3 Feeling of difference and telling someone 40 4.4 Gay and at school 51 4.5 Difficulties at work related to sexual orientation 59 4.6 Society’s attitudes to people of a non-heterosexual orientation 63 4.7 Factors relating to negative reactions to sexual orientation and 68 unconnected factors on mental health, suicidal ideation and self-harm 4.8 How are the needs of young same-sex attracted men currently being met? 73 5. -

1 Introducing LGBTQ Psychology

1 Introducing LGBTQ psychology Overview * What is LGBTQ psychology and why study it? * The scientific study of sexuality and ‘gender ambiguity’ * The historical emergence of ‘gay affirmative’ psychology * Struggling for professional recognition and challenging heteronormativity in psychology What is LGBTQ psychology and why study it? For many people it is not immediately obvious what lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer (LGBTQ) psychology is (see the glossary for defini- tions of words in bold type). Is it a grouping for LGBTQ people working in psychology? Is it a branch of psychology about LGBTQ people? Although LGBTQ psychology is often assumed to be a support group for LGBTQ people working in psychology, it is in fact the latter: a branch of psychology concerned with the lives and experiences of LGBTQ people. Sometimes it is suggested that this area of psychology would be more accurately named the ‘psychology of sexuality’. Although LGBTQ psychology is concerned with sexuality, it has a much broader focus, examining many different aspects of the lives of LGBTQ people including prejudice and discrimination, parenting and families, and com- ing out and identity development. One question we’re often asked is ‘why do we need a separate branch of psychology for LGBTQ people?’ There are two main reasons for this: first, as we discuss in more detail below, until relatively recently most psychologists (and professionals in related disciplines such as psychiatry) supported the view that homosexuality was a mental illness. ‘Gay affirmative’ psychology, as this area was first known in the 1970s, developed to challenge this perspective and show that homosexuals are psychologically healthy, ‘normal’ individuals. -

Lesbian and Bisexual Women's Experiences with Dating and Romantic Relationships During Adolescence Indria Michelle Jenkins Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2013 Lesbian and bisexual women's experiences with dating and romantic relationships during adolescence Indria Michelle Jenkins Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Jenkins, Indria Michelle, "Lesbian and bisexual women's experiences with dating and romantic relationships during adolescence" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13453. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13453 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lesbian and bisexual women’s experiences with dating and romantic relationships during adolescence by Indria Michelle Jenkins A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Psychology (Counseling Psychology) Program of Study Committee: Carolyn Cutrona, Major Professor David Vogel Douglas Gentile Mary Jane Brotherson Karen Scheel Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2013 Copyright @ Indria Michelle Jenkins, 2013. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………..iii 2. ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………..iv 3. CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………..…1 4. CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW………………………………………….…......8 5. CHAPTER 3: METHODS………………………………………………………………20 6. CHAPTER 4: PRESENTATION &ANALYSIS OF FINDINGS…………………......44 7. CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS…………………..……102 8. APPENDIX A: Recruiting Email……………………………………………….…..…111 9. APPENDIX B: Consent Form………………………………………………….……..112 10. APPENDIX C: Interview Guide………………………………………………..…..…116 11.