Mountaineering and War on the Siachen Glacier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications By Name: Syeda Batool National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 1 The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications by Name: Syeda Batool M.Phil Pakistan Studies, National University of Modern Languages, 2019 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY in PAKISTAN STUDIES To FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, DEPARTMENT OF PAKISTAN STUDIES National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 @Syeda Batool, April 2019 2 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES THESIS/DISSERTATION AND DEFENSE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have read the following thesis, examined the defense, are satisfied with the overall exam performance, and recommend the thesis to the Faculty of Social Sciences for acceptance: Thesis/ Dissertation Title: The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications Submitted By: Syed Batool Registration #: 1095-Mphil/PS/F15 Name of Student Master of Philosophy in Pakistan Studies Degree Name in Full (e.g Master of Philosophy, Doctor of Philosophy) Degree Name in Full Pakistan Studies Name of Discipline Dr. Fazal Rabbi ______________________________ Name of Research Supervisor Signature of Research Supervisor Prof. Dr. Shahid Siddiqui ______________________________ Signature of Dean (FSS) Name of Dean (FSS) Brig Muhammad Ibrahim ______________________________ Name of Director General Signature of -

Sherpi Kangri II, Southeast Ridge Pakistan, Karakoram, Saltoro Group

AAC Publications Sherpi Kangri II, Southeast Ridge Pakistan, Karakoram, Saltoro Group Sherpi Kangri II (ca 7,000m according to Eberhard Jurgalski and the Miyamori and Seyfferth maps; higher and lower heights also appear in print) lies at 35°28'45"N, 76°48'21"E on the Line of Control between the India- and Pakistan-controlled sectors of the East Karakoram. Prior to 2019, it had been attempted only once. In 1974, a Japanese expedition trying the east ridge of Sherpi Kangri I (7,380m) gave up and instead reported fixing around 1,000m of rope up the southeast ridge of Sherpi Kangri II, before retreating at 6,300m due to technical difficulty. On August 7, Matt Cornell, Jackson Marvel, and I (all USA) summited this peak via the southeast ridge in seven days round trip from base camp. Porter shortages resulted in a significantly lower base camp than we had planned—at around 3,700m on the west bank of the Sherpi Gang Glacier, more or less level with the first icefall. This required establishing three additional camps several kilometers apart, ferrying loads through complicated terrain, to reach the glacier plateau below the peak. After investing much time and energy on this approach, including portering some of our own loads to base camp, we did not have time to acclimatize as slowly as we would have liked for higher elevations. We therefore chose the seemingly nontechnical southeast ridge, so that we could bail quickly if one of us began to show signs of acute altitude sickness. We climbed to the summit from our highest glacier camp over two days, with one bivouac on the ridge. -

Distribution of Bufotes Latastii (Boulenger, 1882), Endemic to the Western Himalaya

Alytes, 2018, 36 (1–4): 314–327. Distribution of Bufotes latastii (Boulenger, 1882), endemic to the Western Himalaya 1* 1 2,3 4 Spartak N. LITVINCHUK , Dmitriy V. SKORINOV , Glib O. MAZEPA & LeO J. BORKIN 1Institute Of Cytology, Russian Academy Of Sciences, Tikhoretsky pr. 4, St. Petersburg 194064, Russia. 2Department of Ecology and EvolutiOn, University of LauSanne, BiOphOre Building, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland. 3 Department Of EvOlutiOnary BiOlOgy, EvOlutiOnary BiOlOgy Centre (EBC), Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. 4ZoOlOgical Institute, Russian Academy Of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 1, St. PeterSburg 199034, Russia. * CorreSpOnding author <[email protected]>. The distribution of Bufotes latastii, a diploid green toad species, is analyzed based on field observations and literature data. 74 localities are known, although 7 ones should be confirmed. The range of B. latastii is confined to northern Pakistan, Kashmir Valley and western Ladakh in India. All records of “green toads” (“Bufo viridis”) beyond this region belong to other species, both to green toads of the genus Bufotes or to toads of the genus Duttaphrynus. B. latastii is endemic to the Western Himalaya. Its allopatric range lies between those of bisexual triploid green toads in the west and in the east. B. latastii was found at altitudes from 780 to 3200 m above sea level. Environmental niche modelling was applied to predict the potential distribution range of the species. Altitude was the variable with the highest percent contribution for the explanation of the species distribution (36 %). urn:lSid:zOobank.Org:pub:0C76EE11-5D11-4FAB-9FA9-918959833BA5 INTRODUCTION Bufotes latastii (fig. 1) iS a relatively cOmmOn green toad species which spreads in KaShmir Valley, Ladakh and adjacent regiOnS Of nOrthern India and PakiStan. -

Download Deployment Map.Pdf

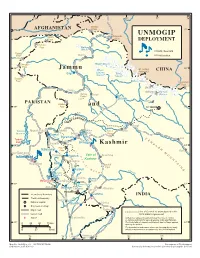

73o 74o 75o 76o 77o 78o Mintaka 37o AFGHANISTAN Pass 37o --- - UNMOGIP Darkot Khunjerab Pass Pass DEPLOYMENT - Thui- An Pass Batura- Glacier UN HQ / Rear HQ Chumar Khan- Baltit UN field station Pass Shandur- Hispar Glacier Pass 36o 36o Jammu Chogo Mt. Godwin CHINA Lungma Austin (K2) Gilgit Biafo 8611m Glacier Glacier Dadarili Baltoro Glacier Pass Karakoram Pass Sia La - Chilas Bilafond La Siachen Nanga Astor Glacier Parbat -- 8126m Skardu PAKISTAN Goma Babusar-- 35o Pass and 35o NJ 980420 X Kel ONTR C O F L LINE O - s a r Kargil D Tarbela Muzaffarabad- Tithwal- Wular Zoji La Dras- Reservoir Sopur Lake Pass Domel J h Jhe ---- e am Baramulla a m Z - Leh Tarbela A Dam Uri Srinagar- N Chakothi Kashmir S o o 34 K - 34 Haji-- Pir A - R Rawalakot Pass P - - - i- Karu Campbellpore Islamabad r M - O Titrinot P Vale of Anantnag Islamabad--- Poonch U a Kashmir N Mendhar n T Rawalpindi- Kotli j - A a- Banihal I ch l Pass N - n u R S P Rajouri C a n hen - Mangla g e ab Reservoir Naushahra- - Mangla Dam New Mirpur- Riasi 33o Munawwarwali- 33o - Jhelum Tawi Bhimber Chhamb Udhampur Akhnur- NW 605550 X International boundary Jammu INDIA - b Provincial boundary - na Gujrat he C - National capital Sialkot- Samba City, town or village Major road Kathua Line of Control as promulgated in the Lesser road 1972 SIMLA Agreement -- vi Airport Gujranwala Ra Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. 32o The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not been agreed 32o 0 25 50 75 km upon by the parties. -

1962 Sino-Indian Conflict : Battle of Eastern Ladakh Agnivesh Kumar* Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India

OPEN ACCESS Freely available online Journal of Political Sciences & Public Affairs Editorial 1962 Sino-Indian Conflict : Battle of Eastern Ladakh Agnivesh kumar* Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India. E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL protests. Later they also constructed a road from Lanak La to Kongka Pass. In the north, they had built another road, west of the Aksai Sino-Indian conflict of 1962 in Eastern Ladakh was fought in the area Chin Highway, from the Northern border to Qizil Jilga, Sumdo, between Karakoram Pass in the North to Demchok in the South East. Samzungling and Kongka Pass. The area under territorial dispute at that time was only the Aksai Chin plateau in the north east corner of Ladakh through which the Chinese In the period between 1960 and October 1962, as tension increased had constructed Western Highway linking Xinjiang Province to Lhasa. on the border, the Chinese inducted fresh troops in occupied Ladakh. The Chinese aim of initially claiming territory right upto the line – Unconfirmed reports also spoke of the presence of some tanks in Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) – Track Junction and thereafter capturing it general area of Rudok. The Chinese during this period also improved in October 1962 War was to provide depth to the Western Highway. their road communications further and even the posts opposite DBO were connected by road. The Chinese also had ample animal In Galwan – Chang Chenmo Sector, the Chinese claim line was transport based on local yaks and mules for maintenance. The horses cleverly drawn to include passes and crest line so that they have were primarily for reconnaissance parties. -

HM 14 APRIL Page 3.Qxd

THE HIMALAYAN MAIL Q JAMMU Q WEDNESDAY Q APRIL 14, 2021 JAMMU & KASHMIR 3 Div Com visits Mukhdoom Sahab Siachen warriors celebrates ‘Siachen Day’ HIMALAYAN MAIL NEWS Shrine, Chatti Padshahi JAMMU, APR 13 On 13 April 2021, Siachen Gurudwara, Ganpatyar Temple Warriors celebrated the 37th Siachen Day with place for devotees, visiting tremendous zeal and enthu- during the festival days. siasm. Brigadier Gurpal He said that today's festi- Singh, SM laid a wreath on vals which are being cele- behalf of GOC, Fire & Fury brated with harmony and Corps and paid homage to brotherhood adds colour to the martyrs at the Siachen its festivity. He said these War Memorial, Base Camp festivals strengthen the to commemorate their bonds of love among people courage and fortitude in se- and nurture amity and har- curing the highest and cold- mony in J&K. est battlefield of the World. During the visit, the com- On this day in 1984, In- mittees of places apprised dian troops first unfurled not only in the face of enemy Soldier continues to guard Siachen Warriors who the Div Com about their is- the tri colour at Bilafond La but also in the face of icy the Frozen Frontier with de- served their motherland sues and demands. He gave launching Operation Megh- peaks with extreme termination and resolve while successfully thwarting HIMALAYAN MAIL NEWS Padshahi Rainawari and arrangements being put in patient hearing to them as- doot. Since then, it has been weather. against all odds. The enemy designs over the SRINAGAR, APR 13 extended his greetings on place for the Holy month of suring that all their genuine a saga of valour and audacity To this day, the Siachen Siachen Day honours all the years. -

Leh Highlights

LEH HIGHLIGHTS 08 NIGHTS / 09 DAYS DELHI – LEH – SHEY – HEMIS – THIKSEY – LEH – NUBRA – ALCHI – LIKIR – LAMAYURU – PANGONG - LEH – DEPARTURE TOUR PROGRAMME: Day 01 ARRIVE DELHI Arrive at Delhi International airport. Upon arrival, you will be met by your car with chauffeur for the short transfer to your hotel for night stay. Rest of the day free. Night in Delhi Day 02: Fly to Leh (via Flight) (11562 i.e. 3524 mts) After breakfast, in time fly to Leh. On arrival you will be met our representative and drive towards the hotel. Welcome drink on arrival. We recommend you completely relax for the rest of the day to enable yourselves to acclimatize to the rarefied air at the high altitude. Dinner and night stay at Hotel in Leh. Day 03: Leh to Shey/Hemis/ Thiksey – Leh (70 Km. (3-4 hours Approx.) After breakfast visit Shey, Hemis, & Thiksey Monastery.Hemis – which is dedicated to Padmasambhava, what a visitor can observes a series of scenes in which the lamas, robed in gowns of rich, brightly colored brocade and sporting masks sometimes bizarrely hideous, parade in solemn dance and mime around the huge flag pole in the center of the courtyard to the plaintive melody of the Shawn. Thiksey –is one of the largest and most impressive Gompas. There are several temples in this Gompa containing images, stupas and exquisite wall paintings. It also houses a two ‐ storied statue of Buddha which has the main prayer hall around its shoulder. Shey – it was the ancient capital of Ladakh and even after Singe Namgyal built the more imposing palace at Leh, the kings continued to regard Shey, as their real home. -

2019 年 6 月・中印・印パ国境辺境高地の旅 (Rev 2020 0602)

1 2019 年 6 月・中印・印パ国境辺境高地の旅 (REV 2020 0602) 付・ラダック北部とヌブラ谷地方の外国人旅行地域解放の最新情報 沖 允人(Masato OKI) (1) 天空の中印国境を行く 国境をめぐる争い 1962 年、インド北東部の Pangong Range(パンゴン山脈)の南東にある Chushul(4337m、チュスル、標高や地名綴 りは地図や文献により違うので以下は Leomann Map に準拠した)周辺、および、アクサイチンとチャンタン地区 (Aksaichin,Changthang Region)でインドと中国は、熾烈な戦いをした。発端は、中国側の主張は、インド側の兵士が Mcmahone Line(マクマホン・ライン・注1)の北側(中国側)に侵入したといい、インド側の主張は中国軍がインド領で ある東北辺境地区(NEFA,North-East Frontiea Agency・注 2)に侵攻したという、1956 年頃から続いているチベットを 巡る中国とインドとの対立の続きだといわれている。1962 年の戦いの結果はインド側の勝利に終わったが、インド側 は 1383 名、中国側は約 722 名の戦死者がでたという(中印国境紛争・Wikipedia)。 1947 年の第一次中印国境紛争後、Aksaichin に中国人民解放軍が侵攻、中華人民共和国が実効支配をするようにな ると、パキスタンもそれに影響を受け、間もなく、パキスタン正規軍も投入され、カシミール西部を中心に戦闘が行な われた。国際連合は 1948 年 1 月 20 日の国際連合安全保障理事会決議 39 でもって停戦を求めたが、戦争は継続され、 停戦となったのは 1948 年 12 月 31 日のことであった。停戦監視のため、国際連合インド・パキスタン軍事監視団 (UNMOGIP)が派遣されたが、恒久的な和平は結ばれず、1965 年に第二次印パ戦争が勃発することとなる。 1965 年 8 月にパキスタンは武装集団をインド支配地域へ送り込んだ。これにインド軍が反応し、1965 年、第二次 印パ戦争が勃発した。なお、その後、インドと中国・パキスタンの間で直接的な交戦は起こっていないが、中国による パキスタン支援は、インドにとって敵対性を持つものであった。2010 年 9 月にはインドは核弾頭の搭載が可能な中距 離弾道ミサイルをパキスタンと中国に照準を合わせて配備すると表明した。これらの戦争の結果、カシミールの 6 割 はインドの実効支配するところとなり、残りがパキスタンの支配下となった(第二次印パ戦争 Wikipedia)。最近のイ ンド・パキスタン情勢は「ヒマラヤ」489 号、2019 年・夏号・60-61 頁によると、印パ関係は悪化しているという。 以上のように、中印国境と印パ国境地帯をめぐる「天空の争い」は根が深く、現在は一応、平穏に見えているが、何 時この均衡が破れるかもしれないという、両国にとって気の抜けない地帯である。もちろん両国は、かなりの軍事施 設を国境地帯に構築し、多くの軍隊を駐屯させている。 このような状況から、インド政府は Chushul やその南東の中国国境に近い Hanle(4350m)とその周辺は外国人の立 ち入りを厳しく制限していた。 なお、2020 年 6 月 2 日の中日新聞朝刊 3 面の北京発の情報によると、中国がパンゴン湖の周辺などでインドに越境 して不穏に情勢だと報じている。 Hanle 解放のニュース 政情がどう変化したか察知できないが、2018 年末に、Hanle が外国人に開放されるというニュースが入り、2019 年 4 月から特別許可が発行されるという情報が、私の懇意にしているレーの旅行社 -

Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring

SANDIA REPORT SAND2007-5670 Unlimited Release Printed September 2007 Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring Brigadier (ret.) Asad Hakeem Pakistan Army Brigadier (ret.) Gurmeet Kanwal Indian Army with Michael Vannoni and Gaurav Rajen Sandia National Laboratories Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. -

Siachen: the Non-Issue, by Prakash Katoch

Siachen: The Non-Issue PC Katoch General Kayani’s call to demilitarise Siachen was no different from a thief in your balcony asking you to vacate your apartment on the promise that he would jump down. The point to note is that both the apartment and balcony are yours and the thief has no business to dictate terms. Musharraf orchestrated the Kargil intrusions as Vajpayee took the bus journey to Lahore, but Kayani’s cunning makes Musharraf look a saint. Abu Jundal alias Syed Zabiuddin an Indian holding an Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) provisioned Pakistani passport has spilled the beans on the 26/11 Mumbai terror attack: its complete planning, training, execution and minute-to-minute directions by the Pakistani military-ISI-LeT (Lashkar-e-Tayyeba) combine. More revealing is the continuing training for similar attacks under the marines in Karachi and elsewhere. The US says Pakistan breeds snakes in its backyard but Pakistan actually beds vipers and enjoys spawning more. If Osama lived in Musharraf’s backyard, isn’t Kayani dining the Hafiz Saeeds and Zaki-Ur- Rehmans, with the Hamid Guls in attendance? His demilitarisation remark post the Gyari avalanche came because maintenance to the Pakistanis on the western slopes of Saltoro was cut off. Yet, the Indians spoke of ‘military hawks’ not accepting the olive branch, recommending that a ‘resurgent’ India can afford to take chances in Siachen. How has Pakistan earned such trust? If we, indeed, had hawks, the cut off Pakistani forces would have been wiped out, following the avalanche. Kashmir Facing the marauding Pakistani hordes in 1947, when Maharaja Hari Singh acceded his state to India, Kashmir encompassed today’s regions of Kashmir Valley, Jammu, Ladakh (all with India), the Northern Areas, Gilgit-Baltistan, Lieutenant General PC Katoch (Retd) is former Director General, Information Systems, Army HQ and a Delhi-based strategic analyst. -

A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan

The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan PhD Thesis Submitted by Ehsan Mehmood Khan, PhD Scholar Regn. No. NDU-PCS/PhD-13/F-017 Supervisor Dr Muhammad Khan Department of Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Faculties of Contemporary Studies (FCS) National Defence University (NDU) Islamabad 2017 ii The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan PhD Thesis Submitted by Ehsan Mehmood Khan, PhD Scholar Regn. No. NDU-PCS/PhD-13/F-017 Supervisor Dr Muhammad Khan This Dissertation is submitted to National Defence University, Islamabad in fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Peace and Conflict Studies Department of Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Faculties of Contemporary Studies (FCS) National Defence University (NDU) Islamabad 2017 iii Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for Doctor of Philosophy in Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Department NATIONAL DEFENCE UNIVERSITY Islamabad- Pakistan 2017 iv CERTIFICATE OF COMPLETION It is certified that the dissertation titled “The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan” written by Ehsan Mehmood Khan is based on original research and may be accepted towards the fulfilment of PhD Degree in Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS). ____________________ (Supervisor) ____________________ (External Examiner) Countersigned By ______________________ ____________________ (Controller of Examinations) (Head of the Department) v AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis titled “The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan” is based on my own research work. Sources of information have been acknowledged and a reference list has been appended. -

Three Visions of Rimo III 8000Ers

20 T h e A l p i n e J o u r n A l 2 0 1 3 Ten minutes after news of the pair’s success was communicated from the summit to basecamp, Agnieszka Bielecka got a radio message from Gerf- ried Göschl’s team to say they were camped about 300m below the summit SIMON YEARSLEY, MALCOLM BASS and preparing to set off. Making the summit bid Göschl himself, Swiss & RACHEL ANTILL aspirant guide Cedric Hahlen, and Nisar Hussain Sadpara, one of three professional Pakistani mountaineers to have climbed all five Karakoram Three Visions of Rimo III 8000ers. None of them was heard from or seen again. Adam Bielecki and Janusz Golab had reached the 8068m top of Gasherbrum I at 8.30am on 9 March; their novel tactic for winter high altitude climbing of leaving camp at midnight had worked. But the weather window was about to close. They descended speedily but with great care, reaching camp III at 1pm, by which time the weather had seriously deteriorated. Pressing on, they arrived at Camp II at about 5pm, ‘slightly frostbitten and very happy’. On 10 March all four members of the Polish team reached base- camp; both summiteers were suffering from second-degree frostbite, Adam Bielecki to his nose and feet, Janusz Golab to his nose. With concern mounting for Göschl, Hahlen and Nisar Hussain, a rescue helicopter was called, however poor weather stalled any flights until The Polish Gasherbrum team.(Adam Bielecki) the 15th when Askari Aviation was able to fly to 7000m and study the route.