Diagnosis, Prevalence, and Treatment of Halitosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health History

Health History Patient Name ___________________________________________ Date of Birth _______________ Reason for visit ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Past Medical History Have you ever had the following? (Mark all that apply) ☐ Alcoholism ☐ Cancer ☐ Endocarditis ☐ MRSA/VRE ☐ Allergies ☐ Cardiac Arrest ☐ Gallbladder disease ☐ Myocardial infarction ☐ Anemia ☐ Cardiac dysrhythmias ☐ GERD ☐ Osteoarthritis ☐ Angina ☐ Cardiac valvular disease ☐ Hemoglobinopathy ☐ Osteoporosis ☐ Anxiety ☐ Cerebrovascular accident ☐ Hepatitis C ☐ Peptic ulcer disease ☐ Arthritis ☐ COPD ☐ HIV/AIDS ☐ Psychosis ☐ Asthma ☐ Coronary artery disease ☐ Hyperlipidemia ☐ Pulmonary fibrosis ☐ Atrial fibrillation ☐ Crohn’s disease ☐ Hypertension ☐ Radiation ☐ Benign prostatic hypertrophy ☐ Dementia ☐ Inflammatory bowel disease ☐ Renal disease ☐ Bleeding disorder ☐ Depression ☐ Liver disease ☐ Seizure disorder ☐ Blood clots ☐ Diabetes ☐ Malignant hyperthermia ☐ Sleep apnea ☐ Blood transfusion ☐ DVT ☐ Migraine headaches ☐ Thyroid disease Previous Hospitalizations/Surgeries/Serious Illnesses Have you ever had the following? (Mark all that apply and specify dates) Date Date Date Date ☐ AICD Insertion ☐ Cyst/lipoma removal ☐ Pacemaker ☐ Mastectomy ☐ Angioplasty ☐ ESWL ☐ Pilonidal cyst removal ☐ Myomectomy ☐ Angio w/ stent ☐ Gender reassignment ☐ Small bowel resection ☐ Penile implant ☐ Appendectomy ☐ Hemorrhoidectomy ☐ Thyroidectomy ☐ Prostate biopsy ☐ Arthroscopy knee ☐ Hernia surgery ☐ TIF ☐ TAH/BSO ☐ Bariatric surgery -

Nutrition Intake History

NUTRITION INTAKE HISTORY Date Patient Information Patient Address Apt. Age Sex: M F City State Zip Home # Work # Ext. Birthdate Cell Phone # Patient SS# E-Mail Single Married Separated Divorced Widowed Best time and place to reach you IN CASE OF EMERGENCY, CONTACT Name Relationship Home Phone Work Phone Ext. Whom may we thank for referring you? Work Information Occupation Phone Ext. Company Address Spouse Information Name SS# Birthdate Occupation Employer I verify that all information within these pages is true and accurate. _____________________________________ _________________________________________ _____________________ Patient's Signature Patient's Name - Please print Date Health History Height Weight Number of Children Are you recovering from a cold or flu? Are you pregnant? Reason for office visit: Date started: Date of last physical exam Practitioner name & contact Laboratory procedures performed (e.g., stool analysis, blood and urine chemistries, hair analysis, saliva, bone density): Outcome What types of therapy have you tried for this problem(s)? Diet modification Medical Vitamins/minerals Herbs Homeopathy Chiropractic Acupunture Conventional drugs Physical therapy Other List current health problems for which you are being treated: Current medications (prescription and/or over-the-counter): Major hospitalizations, surgeries, injuries. Please list all procedures, complications (if any) and dates: Year Surgery, illness, injury Outcome Circle the level of stress you are experiencing on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being the lowest): -

Medical Terminology

MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM MATCHING EXERCISES ANATOMICAL TERMS 1. uvula a. little grapelike structure hanging above root 2. esophagus of tongue 3. cardiac sphincter b. tube carrying food from pharynx to stomach 4. jejunum c. cul de sac first part of large intestine 5. cecum d. empty second portion of small intestine e. lower esophageal circular muscle 1. ileum a. lower gateway of stomach that opens onto 2. ilium duodenum 3. appendix b. jarlike dilation of rectum just before anal 4. rectal ampulla canal 5. pyloric sphincter c. worm-shaped attachment at blind end of cecum d. bone on flank of pelvis e. lowest part of small intestine 1. peritoneum a. serous membrane stretched around 2. omentum abdominal cavity 3. duodenum b. inner layer of peritoneum 4. parietal peritoneum c. outer layer of peritoneum 5. visceral peritoneum d. first part of small intestine (12 fingers) e. double fold of peritoneum attached to stomach 1. sigmoid colon a. below the ribs' cartilage 2. bucca b. cheek 3. hypochondriac c. s-shaped lowest part of large intestine 4. hypogastric above rectum 5. colon d. below the stomach e. large intestine from cecum to anal canal SYMPTOMATIC AND DIAGNOSTIC TERMS 1. anorexia a. bad breath 2. aphagia b. inflamed liver 3. hepatomegaly c. inability to swallow 4. hepatitis d. enlarged liver 5. halitosis e. loss of appetite 1. eructation a. excess reddish pigment in blood 2. icterus b. liquid stools 3. hyperbilirubinemia c. vomiting blood MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 4. hematemesis d. belching 5. diarrhea e. jaundice 1. steatorrhea a. narrowing of orifice between stomach and 2. -

Signs and Symptoms of Oral Cancer

Signs and Symptoms of Oral Cancer l A sore in the mouth that does not heal l A white or red patch on the gums, tongue, tonsils or lining of the mouth l Pain, tenderness or numbness anywhere in your mouth or lip that does not go away l Trouble chewing or swallowing Quitting all forms of tobacco use is critical for good oral health and the prevention of serious or deadly diseases. Call the Mississippi Tobacco Quitline for free assistance to help you quit. 1-800-QUIT-NOW (1-800-784-8669) www.quitlinems.com MISSISSIPPI STATE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 5271 Revised 11-30-17 Tobacco doesn’t just stain your teeth and give you bad breath. Smoking and using spit tobacco are closely connected to tooth MOUTH – There is a strong link between cancer loss and cancer of the head and neck. Your risk of oral and of the mouth and tobacco use. About 75% of people throat cancer may be even greater if you use tobacco and with cancer of the mouth are tobacco users. drink alcohol frequently. TEETH – Spit tobacco use stains the teeth and may cause Any tobacco use can cause infections and diseases tooth pain and tooth loss. Spit tobacco is high in sugar in the mouth. Tobacco includes: and can also cause cavities. l Cigarettes LIPS – Spit tobacco use can cause sores and cancer l Cigars, pipes on the lip. l Little cigars, cigarillos l Snuff, dip, chew CHEEKS – Spit tobacco can cause white sores l E-cigarettes, vaping products on the inner lining of the mouth and tongue, which may turn to cancer. -

Eating Disorders

From the office of: D. Young Pham, DDS 1415 Ridgeback Rd Ste 23 Chula Vista, CA 91910-6990 (619) 421-2155 I Fact Sheet Eating Disorders I Eating Disorders Eating disorders are real, complex, and often devastating condi- tions that can have serious consequences on your overall health and oral health. Telltale early signs of eating disorders often ap- pear in and around the mouth. A dentist may be the first person to notice the symptoms of an eating disorder and to encourage his or her patient to get help. What are the different types of eating disorders? • Anorexia nervosa is a serious, potentially life-threatening eating disorder characterized by self-starvation and excessive weight loss. • Bulimia nervosa is a serious, potentially life-threatening eating disorder characterized by a cycle of bingeing and compensatory behaviors (i.e., self-induced vomiting, use of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas) designed to undo or compensate for the effects of binge eating. • Binge eating is an eating disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of uncontrollable eating without the regular use of compensatory measures to counter the effects of excessive eating. Binge eating may occur on its own or in the context of other eating disorders. • Pica is an eating disorder that is described as “the hunger or craving for non-food substances.” It involves a person per- sistently mouthing and/or ingesting non-nutritive substances (i.e., coal, laundry starch, plaster, pencil erasers, and so forth) for at least a period of one month at an age when this behav- ior is considered developmentally inappropriate. How do eating disorders affect health? Eating disorders can rob the body of adequate minerals, vita- mins, proteins, and other nutrients needed for good health. -

Acid Reflux Hilliard Pediatrics, Inc

Acid Reflux Hilliard Pediatrics, Inc. - Dr. Tim Teller, MD Introduction Acid reflux is a common condition for children. Acid reflux means that acid and stomach contents (food or drink) come back up from the stomach into the esophagus (the connection between the mouth and stomach). From there it may go back down into the stomach, up into the mouth then swallowed again, get thrown up, or go down into the respiratory tract (what is called ‘aspiration’). Acid reflux is also called gastroesophageal reflux or GER. Infants with Acid Reflux When infants have acid reflux, it is important to separate this from normal infant spitting. Many (almost all) infants spit-up some amount of breast milk or formula. It may be a small mouthful or may at times seem like a whole feeding. Many of these infants have no significant pain, grow well, feed well, and improve as the months go by. For infants, the connection between the stomach and esophagus may allow things to come up as the stomach churns, even if months later it works just fine, keeping the reflux from happening. For infants with reflux, the signs and symptoms can vary from infant to infant. It can start right after birth but typically shows up and worsens between the 2 week and 2 month check- ups, sometimes later. Any of these symptoms can occur: excessive crying, refusing to eat, irritability during feedings, arching of the back during feedings, chronic nasal and throat congestion, chronic cough, spitting up, choking or gagging, breath holding or apnea, chewing, sour or bad breath, and poor weight gain. -

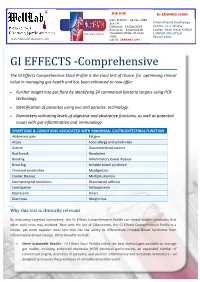

GI EFFECTS -Comprehensive

JOE DOE CHANDr.EDWARD CHAN Date of Birth: 08-Jan-1985 Sex: M International Psychology Collected: 31/Oct/2019 Centre 11-1 Wisma Received: 31/Oct/2019 Laxton Jalan Desa KUALA INTERNATIONAL PATIENT LUMPUR MALAYSIA 1000 58100 1000 www.MalaysiaLaboratory.com Lab id: 3640442 UR#: GI EFFECTS -Comprehensive The GI Effects Comprehensive Stool Profile is the stool test of choice for optimising clinical value in managing gut health and has been enhanced to now offer: Further insight into gut flora by identifying 24 commensal bacteria targets using PCR technology. Identification of parasites using ova and parasite technology. Biomarkers indicating levels of digestive and absorptive functions, as well as potential issues with gut inflammation and immunology. SYMPTOMS & CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH ABNORMAL GASTROINTESTINAL FUNCTION Abdominal pain Fatigue Atopy Food allergy and sensitivities Autism Gastrointestinal cancers Bad breath Headaches Bloating Inflammatory bowel disease Brain fog Irritable bowel syndrome Chemical sensitivities Maldigestion Coeliac Disease Multiple sclerosis Dermatological conditions Rheumatoid arthritis Constipation Schizophrenia Depression Ulcers Diarrhoea Weight loss Why this test is clinically relevant By evaluating targeted biomarkers, the GI Effects Comprehensive Profile can reveal hidden conditions that other stool tests may overlook. Now with the use of Calprotectin, the GI Effects Comprehensive Profile is a simple, yet more superior stool test that has the ability to differentiate Irritable Bowel Syndrome from Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Other benefits include: More Actionable Results - GI Effects Stool Profiles utilise the best technologies available to manage gut health, including enhanced molecular (PCR) technical performance, an expanded number of commensal targets, detection of parasites, and premier inflammatory and metabolic biomarkers – all designed to increase the prevalence of clinically actionable results. -

Review of Systems/Medical and Family History Update

REVIEW OF SYSTEMS/MEDICAL UPDATE CHILD IN THE PAST MONTH, HAS YOUR CHILD EXPERIENCED ANY OF THESE PROBLEMS: General, constitutional Recent weight change NO YES Fever NO YES Musculoskeletal Fatigue NO YES Joint pain NO YES Joint stiffness or swelling NO YES Eyes and vision Weakness of muscles/joints NO YES Eye injury NO YES Muscle pain or cramps NO YES Glasses or contacts NO YES Back pain NO YES Blurred or double vision NO YES Glaucoma NO YES Skin and breasts Rash or itching NO YES Ears, nose, throat Change in skin color NO YES Hearing loss NO YES Change in hair or nails NO YES Ringing in the ears NO YES Dry skin NO YES Sinus problems NO YES Breast lump NO YES Nose bleeds NO YES Breast discharge NO YES Mouth sores NO YES Bleeding gums NO YES Neurological Bad breath or bad taste NO YES Frequent or recurrent headaches NO YES Sore throat or voice change NO YES Lightheaded or dizzy NO YES Convulsions or seizures NO YES Heart and cardiovascular Numbness or tingling sensations NO YES Heart trouble NO YES Tremors NO YES Chest pains NO YES Weakness NO YES Sudden heartbeat changes NO YES Head injury NO YES Respiratory Psychiatric Frequent coughing NO YES Nervousness NO YES Shortness of breath NO YES Depression NO YES Asthma or wheezing NO YES Sleep problems NO YES Gastrointestinal Endocrine Loss of appetite NO YES Glandular or hormone problem NO YES Change in bowel movements NO YES Thyroid disease NO YES Nausea or vomiting NO YES Diabetes NO YES Frequent diarrhea NO YES Excessive thirst or urination NO YES Painful bowel movements/constipation NO YES Heat or cold intolerance NO YES Blood in stool NO YES Stomach pain NO YES Hematology/Lymphatic Slow to heal after cuts NO YES Genitourinary Easy bruising or bleeding NO YES Frequent urination NO YES Anemia NO YES Burning or painful urination NO YES Transfusion NO YES Blood in urine NO YES Swollen glands NO YES Urine accidents NO YES Kidney stones NO YES Female: Painful periods NO YES Female: Irregular periods NO YES Please give the date of last menstrual period. -

Dysphagia What Is Dysphagia? Dysphagia Is a General Term Used to Describe Difficulty Swallowing

Dysphagia What is Dysphagia? Dysphagia is a general term used to describe difficulty swallowing. While swallowing may seem very involuntary and basic, it’s actually a rather complex process involving many different muscles and nerves. Swallowing happens in 3 different phases: Insert Shutterstock ID: 119134822 1. During the first phase or oral phase the tongue moves food around in your mouth. Chewing breaks food down into smaller pieces, and saliva moistens food particles and starts to chemically break down our food. 2. During the pharyngeal phase your tongue pushes solids and liquids to the back of your mouth. This triggers a swallowing reflex that passes food through your throat (or pharynx). Your pharynx is the part of your throat behind your mouth and nasal cavity, it’s above your esophagus and larynx (or voice box). During this reflex, your larynx closes off so that food doesn’t get into your airways and lungs. 3. During the esophageal phase solids and liquids enter the esophagus, the muscular tube that carries food to your stomach via a series of wave-like muscular contractions called peristalsis. Insert Shutterstock ID: 1151090882 When the muscles and nerves that control swallowing don’t function properly or something is blocking your throat or esophagus, difficulty swallowing can occur. There are varying degrees of Dysphagia and not everyone will describe the same symptoms. Your symptoms will depend on your specific condition. Some people will experience difficulty swallowing only solids, or only dry solids like breads, while others will have problems swallowing both solids and liquids. Still others won’t be able to swallow anything at all. -

Oral Malodour– Background and Diagnostics

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !"#$%&#$'(')"! *%+#,-."')/(%#/(%(0#./'120,1%% ! % ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 3#"'%40/5#6#7'% ! 89:,9%;<=,7>?%@=/2#$%12)(=/2%%%%%%%%%%%%%% ! 3#"'940/5#6#7'A7=$10/-09B0%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% ! CC9DD9CEDE%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% 402="#$%12)(F%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% ! G/12"),2'"H%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% I"'B=11'"%J)--#%K9%8=)"&#/% !"#$%&'#()*+,*-%.'#"/#*0 *1234.()*+,*5%6#3#"%*0 * 7"'(#(4(%*+,*8%"(#'(&)* "! ! ! #$%&'()'(!*%'+,'&-+!!!#$%&'().+/&!0('1$/&'-$-! -234356789:+;9;8<!!!.956=838:&3582<7!>!.9?6=8@! %928<;!!!'7;828682<7!>!A3B9C8D378! Faculty of Medicine Institute of Dentistry -352EF ! .GCH9889C3!>!I68J<C! ! M.Sc. (Tech), Dental student Aaro Linja-aho! -@G7!72D2 !!ICK3838;!8283=!>!-28=3! Oral malodour – background and diagnostics +BB29273!!!%FC<FD73!>!&6KE3?8! Oral Infectious Diseases -@G7!=9E2 !!ICK3838;!9C8!>!%3L3=! I259 !!A986D!>!M<78J!974!@39C! &2L6DFFCF N&24<9789=!N!(6DK3C!<H!B9O3;! Review! 11/2010! !""PQR! ! -22L2;83=DF !!/3H3C98!>!IK;8C9?8! ! S94!KC398J!<C!<C9=!D9=<4<6C!?97!K3!C3=9834!8<!O27O2L9=!42;39;3;T!8C2D38J@=9D276C29T!L9C2<6;! 27H=9DD982<7!42;39;3;!<H!6BB3C!C3;B2C98<C@!8C9?8T!H<C32O7!K<423;!27!79;9=!?9L28@!38?U!S94!KC398J!2;! 6;69==@T!27!RV!W!8<!XV!W!<H!?9;3;T!27H=2?834!K@!OC9D!73O982L3!9793C<K2?!K9?83C29!27!8<7O63! ?<9827OU!-J3;3!K9?83C29!J9L3!9!837437?@!<H!BC<46?27O!H<6=N;D3==27O!;6=BJ6C!?<7892727O!O9;3;! ?9==34!L<=982=3!;6=BJ6C!?<DB<674;!<C!1&YU!M927!?96;3!<H!K94!KC398J!2;!B9C<4<78282;!<C!B<;879;9=! -

Adult/Caregiver Handouts

Oral Health Risk Assessment Protocols, Training Modules and Educational Materials for Use with Families of Young Children. Adult/ Caregiver Adult/Caregiver FLUORIDE • Makes teeth stronger and protects them from tooth decay. • Is found naturally in water and some foods. • Is added to many community water systems (tap water) when there isn’t enough natural fluoride. • Is also available through drops, tablets, gels, toothpastes, mouth rinses, and varnishes. • Ask your doctor or dentist which type of fluoride is right for you and your family. 1 BRUSHING AND FLOSSING TEETH • Brush teeth two times a day to remove plaque. • Brush for two-three minutes reaching all teeth. • Brushing should be supervised by an adult until the child is 6-8 years old. • Floss once a day – starting at age 8 with adult assistance. • Replace toothbrush when bristles are frayed. • Wipe the gums of infants with a wet cloth after each feeding. 2 STAINED AND DISCOLORED TEETH Teeth can be discolored or stained on the surface and/or discolored from the inside of the tooth. The stain or discoloration may be all over the tooth or appear as spots or lines in the enamel. Causes: • Trauma to the tooth • High fever when tooth is forming • Excessive fluoride • Taking tetracycline before 8 years of age • Not brushing teeth and gums • Tooth decay • Drinking cola, coffee or tea • Old silver fillings • Tobacco products 3 SPOTS ON TEETH WHAT DOES TOOTH DECAY LOOK LIKE? • White spots on teeth are the first sign of tooth decay. They look chalky and white and are found near the gums where plaque forms. -

Identifying the LINX® Reflux Management System Patient

Identifying the LINX® Reflux Management System Patient Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, or GERD is a chronic What is GERD? digestive disease, caused by weakness or inappropriate relaxation in a muscle called the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Normally, the LES behaves like a one-way valve, allowing food and liquid to pass through to the stomach, but preventing stomach contents from flowing back Symptoms of GERD into the esophagus. • Heartburn • Chest pain • Regurgitation • Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) • Dental erosion and bad breath • Cough • Hoarseness • Sore throat • Asthma Complications * GERD can lead to potentially serious complications including: • Esophagitis (inflammation, irritation or swelling of the esophagus) • Stricture (narrowing of the esophagus) • Barrett’s esophagus (precancerous changes to the esophagus) • Esophageal cancer (in rare cases)** Diagnosing GERD • Response to medication • Endoscopy/EGD • Bravo pH monitoring *LINX is not intended to cure, treat, prevent, mitigate or diagnose these symptoms or complications **0.5% of Barrett’s esophagus patients per year are diagnosed with esophageal cancer ® Who is the LINX Reflux Management System patient? • Diagnosed with GERD as defined by abnormal pH testing • Patients seeking an alternative to continuous acid supression therapy LINX Reflux Management System patient workup • Objective reflux – pH testing • Anatomy – EGD • Esophageal function – Manometry Restore don’t reconstruct1* • Requires no alteration to stomach anatomy • Preserved ability to belch and vomit2† • Removable • Preserves future treatment options1‡ Patient benefits at 5 years1 • 85% of patients were off daily reflux medications after treatment with LINX Reflux Management System§ • Elimination of regurgitation in 99% of patients¶ • 88% elimination of bothersome heartburn** • Patients reported significant improvement in quality of life†† • Patients reported a significant improvement in symptoms of bloating and gas€ References 1.