SAB 002 1979 P15-32 Part 1 Aspects of the Occurrence Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

Initial Study/Environmental Assessment: Kent Island Restoration at Bolinas Lagoon

DRAFT INITIAL STUDY/ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT: KENT ISLAND RESTORATION AT BOLINAS LAGOON Marin County Open Space District and US Army Corps of Engineers San Francisco District August 2012 DRAFT INITIAL STUDY/ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT: KENT ISLAND RESTORATION AT BOLINAS LAGOON PREPARED FOR Marin County Open Space District Marin County Civic Center 3501 Civic Center Drive, Room 260 San Rafael, CA 94903 (415) 499-6387 and US Army Corps of Engineers San Francisco District 1455 Market St San Francisco, CA 94103 (415) 503-6703 PREPARED BY Carmen Ecological Consulting Grassetti Environmental Consulting Peter R. Baye, Coastal Ecologist, Botanist August 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................1 1.1 Purpose of this Document ............................................................................................................1 1.2 Document Structure ..............................................................................................................1 2.0 PROPOSED PROJECT AND ALTERNATIVES .......................................................................3 2.1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................3 2.2 Environmental Setting ..............................................................................................................3 2.3 Purpose and Need ..............................................................................................................6 -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

Revised July 11, 2000

Revised January 29, 2013 U.S. Shorebird Conservation Plan Upper Mississippi Valley/ Great Lakes Regional Shorebird Conservation Plan Version 1.0 Prepared by1: Ferenc de Szalay, Department of Biological Sciences, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio Doug Helmers, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Columbia, Missouri Dale Humburg, Missouri Department of Conservation, Columbia, Missouri Stephen J. Lewis, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Snelling, Minnesota Barbara Pardo, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Snelling, Minnesota Mark Shieldcastle, Ohio Division of Wildlife, Oak Harbor, Ohio May, 2000 1 Authors are listed alphabetically. Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 2 DESCRIPTION OF THE UMVGL REGION ................................................................................ 2 Physical Description ............................................................................................................... 2 Bird Conservation Regions ..................................................................................................... 2 Shorebird Habitats in the UMVGL ......................................................................................... 3 Human Impacts on Shorebird habitat in the UMVGL Region ............................................... 4 SHOREBIRD SPECIES -

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

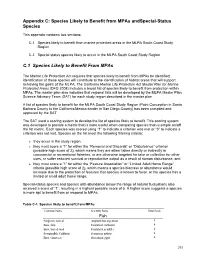

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

Pacific Ocean

124° 123° 122° 121° 42° 42° 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 ° 32 41° 41 31 29 30 27 28 26 25 24 23 22 21 ° ° 40 20 40 19 18 17 16 15 PACIFIC OCEAN 14 13 ° ° 39 12 39 11 10 9 8 6 7 4 5 20 0 20 3 MILES 1 2 38° 38° 124° 123° 122° 121° Prepared for: Office of HAZARDOUS MATERIALS RESPONSE OIL SPILL PREVENTION and RESPONSE and ASSESSMENT DIVISION California Department Of Fish and Game National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Sacramento, California Seattle, Washington Prepared by: RESEARCH PLANNING, INC. Columbia, SC 29202 ENVIRONMENTAL SENSITIVITY INDEX MAP 123°00’00" 122°52’30" 38°07’30" 38°07’30" TOMALES BAY STATE PARK P O I N T R E Y E S N A T I O N A L S E A S H O R E ESTERO DE LIMANTOUR RESERVE POINT REYES NATIONAL SEASHORE 38°00’00" 38°00’00" POINT REYES HEADLAND RESERVE GULF OF THE FARALLONES NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY 123°00’00" 122°52’30" ATMOSPH ND ER A IC IC A N D A M E I Prepared for C N O I S L T R A A N T O I I O T N A N U . E S. RC DE E PA MM RTMENT OF CO Office of HAZARDOUS MATERIALS RESPONSE OIL SPILL PREVENTION and RESPONSE and ASSESSMENT DIVISION California Department of Fish and Game National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 1.50 1KILOMETER 1.50 1MILE PUBLISHED: SEPTEMBER 1994 DRAKES BAY, CALIF. -

First Record of Long-Billed Curlew Numenius Americanus in Peru and Other Observations of Nearctic Waders at the Virilla Estuary Nathan R

Cotinga 26 First record of Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus in Peru and other observations of Nearctic waders at the Virilla estuary Nathan R. Senner Received 6 February 2006; final revision accepted 21 March 2006 Cotinga 26(2006): 39–42 Hay poca información sobre las rutas de migración y el uso de los sitios de la costa peruana por chorlos nearcticos. En el fin de agosto 2004 yo reconocí el estuario de Virilla en el dpto. Piura en el noroeste de Peru para identificar los sitios de descanso para los Limosa haemastica en su ruta de migración al sur y aprender más sobre la migración de chorlos nearcticos en Peru. En Virilla yo observí más de 2.000 individuales de 23 especios de chorlos nearcticos y el primer registro de Numenius americanus de Peru, la concentración más grande de Limosa fedoa en Peru, y una concentración excepcional de Limosa haemastica. La combinación de esas observaciones y los resultados de un estudio anterior en el invierno boreal sugiere la posibilidad que Virilla sea muy importante para chorlos nearcticos en Peru. Las observaciones, también, demuestren la necesidad hacer más estudios en la costa peruana durante el año entero, no solemente durante el punto máximo de la migración de chorlos entre septiembre y noviembre. Shorebirds are poorly known in Peru away from bordered for a few hundred metres by sand and established study sites such as Paracas reserve, gravel before low bluffs rise c.30 m. Very little dpto. Ica, and those close to metropolitan areas vegetation grows here, although cows, goats and frequented by visiting birdwatchers and tour pigs owned by Parachique residents graze the area. -

Migratory Shorebird Guild

Migratory Shorebird Guild Piping Plover Charadrius melodus Sanderling Calidris alba Semipalmated Plover Charadrius semipalmatus Red Knot Calidris canutus Black-bellied Plover Pluvialis squatarola Marbled Godwit Limosa fedoa American Golden Plover Pluvialis dominica Buff-breasted Sandpiper Tryngites subruficollis Wimbrel Numenius phaeopus White-rumped Sandpiper Calidris fuscicollis Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus Pectoral Sandpiper Calidris melanotos Greater Yellowlegs Tringa melanoleuca Purple Sandpiper Calidris maritima Lesser Yellowlegs Tringa flavipes Stilt Sandpiper Calidris himantopus Solitary Sandpiper Tringa solitaria Wilson’s Snipe Gallinago gallinago delicata Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularia American Avocet Recurvirostra Americana Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda Least Sandpiper Calidris minutilla Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla Short-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus griseus Western Sandpiper Calidris mauri Long-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus scolopaceus Dunlin Calidris alpina Contributors: Felicia Sanders and Thomas M. Murphy DESCRIPTION Photograph by SC DNR Taxonomy and Basic Description The migratory shorebird guild is composed of birds in the Charadrii suborder. Migrants in South Carolina represent three families: Scolopacidae (sandpipers), Charadriidae (plovers) and Recurvirostridae (avocets). Sandpipers are the most diverse family of shorebirds. Their tactile foraging strategy encompasses probing in soft mud or sand for invertebrates. Plovers are medium size birds, with relatively short, thick bills and employ a distinctive foraging strategy. They stand, looking for prey and then run to feed on detected invertebrates. Avocets are large shorebirds with long recurved bills and partial webbing between the toes. They feed employing both tactile and visual methods. Shorebirds are characterized by long legs for wading and wings designed for quick flight and transcontinental migrations. Migrations can span continents; for example, red knots migrate from the Canadian arctic to the southern tip of South America. -

54971 GPNC Shorebirds

A P ocket Guide to Great Plains Shorebirds Third Edition I I I By Suzanne Fellows & Bob Gress Funded by Westar Energy Green Team, The Nature Conservancy, and the Chickadee Checkoff Published by the Friends of the Great Plains Nature Center Table of Contents • Introduction • 2 • Identification Tips • 4 Plovers I Black-bellied Plover • 6 I American Golden-Plover • 8 I Snowy Plover • 10 I Semipalmated Plover • 12 I Piping Plover • 14 ©Bob Gress I Killdeer • 16 I Mountain Plover • 18 Stilts & Avocets I Black-necked Stilt • 19 I American Avocet • 20 Hudsonian Godwit Sandpipers I Spotted Sandpiper • 22 ©Bob Gress I Solitary Sandpiper • 24 I Greater Yellowlegs • 26 I Willet • 28 I Lesser Yellowlegs • 30 I Upland Sandpiper • 32 Black-necked Stilt I Whimbrel • 33 Cover Photo: I Long-billed Curlew • 34 Wilson‘s Phalarope I Hudsonian Godwit • 36 ©Bob Gress I Marbled Godwit • 38 I Ruddy Turnstone • 40 I Red Knot • 42 I Sanderling • 44 I Semipalmated Sandpiper • 46 I Western Sandpiper • 47 I Least Sandpiper • 48 I White-rumped Sandpiper • 49 I Baird’s Sandpiper • 50 ©Bob Gress I Pectoral Sandpiper • 51 I Dunlin • 52 I Stilt Sandpiper • 54 I Buff-breasted Sandpiper • 56 I Short-billed Dowitcher • 57 Western Sandpiper I Long-billed Dowitcher • 58 I Wilson’s Snipe • 60 I American Woodcock • 61 I Wilson’s Phalarope • 62 I Red-necked Phalarope • 64 I Red Phalarope • 65 • Rare Great Plains Shorebirds • 66 • Acknowledgements • 67 • Pocket Guides • 68 Supercilium Median crown Stripe eye Ring Nape Lores upper Mandible Postocular Stripe ear coverts Hind Neck Lower Mandible ©Dan Kilby 1 Introduction Shorebirds, such as plovers and sandpipers, are a captivating group of birds primarily adapted to live in open areas such as shorelines, wetlands and grasslands. -

Recent Publications on Waders

Marbled Godwit ate grapsid crabs, with the Marbled Godw•talso consumingbivalves and polychaetes. Western Sandpipers ate a larger diversity of prey, including insects, polychaetes, amphipods, ostracods and oligochaetes. A preliminary comparisonof prey items in stomach-pumpedsamples and stomachs from sacrificed birds indicated concurrence in prey species, but not in relative abundance. Red Phalarope responses to thin oil films in fora•in• experiments Peter G. Connors and Steve Gelman. Bodega Marine Laboratory, University of California, Bodega Bay, CA 94923, U.S.A. In experi•nts using shallowpans of water containingbrine shrimp, juvenile PhalaropesPhalaropus fulicariuSwere presented with a choice of foraging on pans with a thin surface film of oil or on pans with a clear surface. Results indicate that naive birds were equally likely to enter oiled or clear pans on the first choice. However, subsequent choices favored pans without oil, and the duration of feeding bouts differed: birds remained longer on clear pans than on oiled pans (p •.01, Mann-Whitney test). These results suggest that phalaropes can quickly learn to distinguish and to avoid oiled surfaces, but even brief contact with oil at sea may decrease survival. RECENT PUBLICATIONS ON WADERS Compiled by N.C.Davidson & M.W.Pienkowski Although considerable effort is spent on trying to make these lists as complete as possible, coverage is inevitably somewhat dependent on the range of journals, etc. which are available to the compilers. Therefore, details of omissions and, if possible, reprints of papers are always welcome. These should be sent to either of the compilers at: Department of Zoology, University of Durham, South Road, Durham DH1 3LE, England. -

Birds of the Great Plains: Family Scolopacidae (Woodcocks, Snipes, and Sandpipers)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Birds of the Great Plains (Revised edition 2009) by Paul Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2009 Birds of the Great Plains: Family Scolopacidae (Woodcocks, Snipes, and Sandpipers) Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscibirdsgreatplains Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Birds of the Great Plains: Family Scolopacidae (Woodcocks, Snipes, and Sandpipers)" (2009). Birds of the Great Plains (Revised edition 2009) by Paul Johnsgard. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscibirdsgreatplains/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Birds of the Great Plains (Revised edition 2009) by Paul Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. FAMILY SCOLOP ACIDAE (WOODCOCKS, SNIPES, AND SANDPIPERS) Marbled Godwit American Woodcock Philohela minor Breeding Status: Summer resident in west-central and northwest ern Minnesota, with nesting records for Pennington and Becker counties and a summer record from Pope County. Nesting in Iowa is fairly frequent (Iowa Bird Life 46:65) and has occurred in Brookings County, South Dakota (South Dakota Bird Notes 25:6). There is a 1972 nesting record for Sarpy County, Nebraska (Nebraska Bird Review 42:43). There are also three recent Kansas nesting records for Jefferson, Woodson, and Douglas counties (Kansas Ornithological Society Bulletin 26:22, 27:9, 28:22). There is a 1973 breeding record for Payne County, Oklahoma (Ameri can Birds 27:789), and since that time there have been a surprising number of Oklahoma nestings. -

Shorebird Habitat Conservation Strategy

Upper Mississippi River and Great Lakes Region Joint Venture Shorebird Habitat Conservation Strategy May 2007 1 Shorebird Strategy Committee and Members of the Joint Venture Science Team Bob Gates, Ohio State University, Chair Dave Ewert, The Nature Conservancy Diane Granfors, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Bob Russell, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Bradly Potter, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Mark Shieldcastle, Ohio Department of Natural Resources Greg Soulliere, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Cover: Long-billed Dowitcher. Photo by Gary Kramer. i Table of Contents Plan Summary................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements...................................................................................................... 2 Background and Context ................................................................................................. 3 Population Status and Trends ......................................................................................... 6 Habitat Characteristics .................................................................................................. 11 Biological Foundation..................................................................................................... 14 Planning Framework.................................................................................................. 14 Migration and Distribution........................................................................................ 15 Limiting