Uganda Country Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abortion and Postabortion Care in Uganda

FACT SHEET Abortion and Postabortion Care in Uganda ■■ Despite large reductions in pregnancy- ■■ The abortion rate for Uganda is slightly challenge for the Ugandan health related deaths in Uganda over the past higher than the estimated rate for the system. two decades (the maternal mortality East Africa region as a whole, which ratio dropped from 684 per 100,000 was 34 per 1,000 women during High cost of abortion and live births in 1995 to 343 per 100,000 2010–2014. postabortion care in 2015), the high number of maternal ■■ The amount women pay for a clan- deaths there remains a public health ■■ Within Uganda, abortion rates vary destine abortion varies. In 2011–2012, challenge. widely by region, from 18 per 1,000 the average out-of-pocket cost for women in the Western region to 77 an unsafe procedure, treatment of ■■ Unsafe abortion continues to con- per 1,000 in Kampala. complications prior to arriving at a tribute significantly to this public health facility or both was US$23. In health problem: A 2010 report by the Availability of postabortion care 2003, an abortion was estimated to Ugandan Ministry of Health estimated ■■ Of the 2,300 health care facilities cost a woman US$25–88 if performed that 8% of maternal deaths were due across Uganda that can provide post- by a doctor, US$14–31 if performed to unsafe abortion. abortion care, an estimated 89% treat by a nurse or midwife, US$12–34 if postabortion complications. performed by a traditional healer and ■■ Ugandan law explicitly allows abor- US$4–9 if self-induced. -

Prevalence of Maternal Near Miss and Community-Based Risk Factors in Central Uganda

International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 135 (2016) 214–220 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijgo CLINICAL ARTICLE Prevalence of maternal near miss and community-based risk factors in Central Uganda Elizabeth Nansubuga a,b,c,⁎,NatalAyigaa,CherylA.Moyerd a Population Research and Training Unit, North West University, Mafikeng, South Africa b Department of Population Studies, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda c African Studies Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA d Departments of Learning Health Sciences and Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA article info abstract Article history: Objective: To examine the prevalence of maternal near-miss (MNM) and its associated risk factors in a community Received 4 November 2015 setting in Central Uganda. Methods: A cross-sectional research design employing multi-stage sampling collected Received in revised form 19 May 2016 data from women aged 15–49 years in Rakai, Uganda, who had been pregnant in the 3 years preceding the survey, Accepted 26 July 2016 conducted between August 10 and December 31, 2013. Additionally, in-depth interviews were conducted. WHO-based disease and management criteria were used to identify MNM. Binary logistic regression was used to Keywords: predict MNM risk factors. Content analysis was performed for qualitative data. Results: Survey data were collected Maternal near-miss from 1557 women and 40 in-depth interviews were conducted. The MNM prevalence was 287.7 per 1000 pregnan- Pregnancy complications Prevalence cies; the majority of MNMs resulted from hemorrhage. Unwanted pregnancies, a history of MNM, primipara, Risk factors pregnancy danger signs, Banyakore ethnicity, and a partner who had completed primary education only were asso- Uganda ciated with increased odds of MNM (all P b 0.05). -

Evaluation of Antiretroviral Therapy Information System in Mbale Regional Referral Hospital, Uganda

EVALUATION OF ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY INFORMATION SYSTEM IN MBALE REGIONAL REFERRAL HOSPITAL, UGANDA. PETER OLUPOT-OLUPOT A mini-thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Health in the School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape. SUPERVISOR: DR. GAVIN REAGON February 2009 1 KEY WORDS Health Information Systems HIV/AIDS ART Data Quality Timeliness Data Accuracy Data analysis Data use Use of information Availability 2 ACRONYMS AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ACP AIDS Control Program ART Antiretroviral Therapy ART-IS Antiretroviral Therapy Information System ARV Antiretroviral CD4 Cluster of Differentiation 4 CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention EBR Electronic Based Records GFATM Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis & Malaria GOU Government of Uganda IDC Infectious Disease Clinic IMR Infant Mortality Rate HAART Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy HIS Health Information Systems HISP Health Information System Project HIT Health Information Technology HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus HMIS Health Management Information Systems MAP Multi-country AIDS Program MMR Maternal Mortality Rate MOH Ministry of Health MPH Master of Public Health MRRH Mbale Regional Referral Hospital 3 NGO Non Governmental organization OI Opportunistic Infection OpenMRS Open Medical Record System PBR Paper Based Record PDA Personal Digital Assistant PEPFAR President’s (USA) Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief PLWA People Living with HIV/AIDS RHINONET Routine Health Information Network SOPH School of Public Health SSA Sub – Saharan Africa STI Sexually Transmitted Infection TASO The AIDS Support Organization TB Tuberculosis U5MR Under Five Mortality Rate UN United Nations UNAIDS United Nations Joint Program on AIDS UWC University of the Western Cape VCT Voluntary Counseling and Testing WHO World Health Organization 4 About the Evaluation The ART – IS at Mbale regional referral hospital is still an infant system which has been in operation for only 3 years. -

Download Download

Open Access ORIGINAL RESEARCH Assessment of the impact of the new paediatric surgery unit and the COSECSA training programme at Mbarara Hospital, Uganda Anne W. Shikanda, Martin S. Situma Pediatric Surgery Department, Mbarara University Teaching Hospital, Mbarara, Uganda Correspondence: Dr Anne W. Shikanda ([email protected]) © 2019 A.W. Shikanda & M.S. Situma. This open access article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/ East Cent Afr J Surg. 2019 Apr;24(1):133–139 licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ecajs.v24i2.10 Abstract Background This study aimed to assess the impact of a new pediatric surgical unit (PSU) established upcountry in a unique way in a govern- ment hospital with a non-governmental organization as the main stakeholder. The unit is run by one pediatric surgeon trained through COSECSA. It is the second PSU in the country. This PSU brought pediatric surgical services and training closer to the Mbarara community. Methods The study was conducted at Mbarara regional referral hospital (MRRH). It was a cross-sectional mixed design study. For the qual- itative arm, Key Informant interviews were done with the main stakeholders who established the PSU. Impact on training was assessed using a questionnaire to former postgraduate trainees (Alumni). Quantitative arm assessed number of surgeries by a historical audit of hospital operating room registers comparing volume of surgeries before and after the establishment of the unit. -

Psychiatric Hospitals in Uganda

Psychiatric hospitals in Uganda A human rights investigation w www.mdac.org mentaldisabilityadvocacy @MDACintl Psychiatric hospitals in Uganda A human rights investigation 2014 December 2014 ISBN 978-615-80107-7-1 Copyright statement: Mental Disability Advocacy Center (MDAC) and Mental Health Uganda (MHU), 2014. All rights reserved. Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Executive summary ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction, torture standards and hospitals visited.............................................................................................................................. 9 1(A). The need for human rights monitoring........................................................................................................................................................... 9 1(B). Uganda country profile .................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 1(C). Mental health ................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

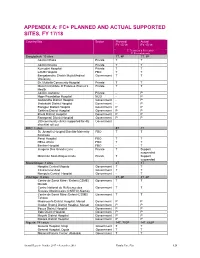

Appendix A: Fc+ Planned and Actual Supported Sites, Fy 17/18

APPENDIX A: FC+ PLANNED AND ACTUAL SUPPORTED SITES, FY 17/18 Country/Site Sector Planned Actual FY 17/18 FY 17/18 T: Treatment & Prevention P: Prevention-only Bangladesh: 15 sites 7T, 4P 7T, 8P Ad-Din Dhaka Private T T Ad-Din Khulna Private T T Kumudini Hospital Private T T LAMB Hospital FBO T T Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical Government T T University Dr. Muttalib Community Hospital Private T T Mamm's Institute of Fistula & Women's Private T T Health Ad-Din Jashohor Private - P Hope Foundation Hospital NGO - P Gaibandha District Hospital Government - P Jhalakathi District Hospital Government - P Rangpur District Hospital Government P P Satkhira District Hospital Government P P Bhola District Hospital Government P P Ranagmati District Hospital Government P P 200 community clinics supported for 4Q Government checklist roll out DRC: 4 sites 5T 4T St. Joseph’s Hospital/Satellite Maternity FBO T T Kinshasa Panzi Hospital FBO T T HEAL Africa FBO T T Beniker Hospital FBO - T Imagerie Des Grands-Lacs Private T Support suspended Maternité Sans Risque Kindu Private T Support suspended Mozambique: 3 sites 2T 3T Hospital Central Maputo Government T T Clinica Cruz Azul Government T T Nampula Central Hospital Government - T WA/Niger: 9 sites 3T, 6P 3T, 6P Centre de Santé Mère / Enfant (CSME) Government T T Maradi Centre National de Référence des Government T T Fistules Obstétricales (CNRFO),Niamey Centre de Santé Mère /Enfant (CSME) Government T T Tahoua Madarounfa District Hospital, Maradi Government P P Guidan Roumji District Hospital, Maradi Government -

October 8, 2014 the Africa Commission on Human And

October 8, 2014 The Africa Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights Re: Supplementary Information on Uganda scheduled for review by the Africa Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights during its 56th Ordinary Session Introduction This letter is intended to supplement the periodic report submitted by Uganda, to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the African Commission) in keeping with Article 62 of the Africa Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Africa Charter),1 which will be reviewed by the Commission. The Center for Reproductive Rights (the Center), a global legal advocacy organization with headquarters in New York, and offices in Nairobi, Bogotá, Kathmandu, Geneva, and Washington, D.C., and the Center for Health, Human Rights and Development (CEHURD) a Ugandan non-governmental organization hope to further the work of the Commission by providing independent information on the rights protected in the African Charter, the Protocol of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol)2, and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (African Children’s Charter)3. The letter provides information on the following issues of greatest concern: lack of access to comprehensive family planning services and information, lack of access to safe abortion services and post-abortion care, the high rates of preventable maternal mortality and morbidity; discrimination against people living with HIV and AIDS; and discrimination against women and girls, including violence, and forced pregnancy testing and expulsion of pregnant school girls. The information in this letter regarding unsafe abortion and lack of access to family planning information and services is drawn from the Center’s fact-finding report, The Stakes are High: The Tragic Impact of Unsafe Abortion and Inadequate Access to Contraception in Uganda (the Stakes are High), 4 which has been submitted with this letter. -

Planned Shutdown Web October 2020.Indd

PLANNED SHUTDOWN FOR SEPTEMBER 2020 SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT AND ROUTINE MAINTENANCE REGION DAY DATE SUBSTATION FEEDER/PLANT PLANNED WORK DISTRICT AREAS & CUSTOMERS TO BE AFFECTED Kampala West Saturday 3rd October 2020 Mutundwe Kampala South 1 33kV Replacement of rotten vertical section at SAFARI gardens Najja Najja Non and completion of flying angle at MUKUTANO mutundwe. North Eastern Saturday 3rd October 2020 Tororo Main Mbale 1 33kV Create Two Tee-offs at Namicero Village MBALE Bubulo T/C, Bududa Tc Bulukyeke, Naisu, Bukigayi, Kufu, Bugobero, Bupoto Namisindwa, Magale, Namutembi Kampala West Sunday 4th October 2020 Kampala North 132/33kV 32/40MVA TX2 Routine Maintenance of 132/33kV 32/40MVA TX 2 Wandegeya Hilton Hotel, Nsooda Atc Mast, Kawempe Hariss International, Kawempe Town, Spencon,Kyadondo, Tula Rd, Ngondwe Feeds, Jinja Kawempe, Maganjo, Kagoma, Kidokolo, Kawempe Mbogo, Kalerwe, Elisa Zone, Kanyanya, Bahai, Kitala Taso, Kilokole, Namere, Lusanjja, Kitezi, Katalemwa Estates, Komamboga, Mambule Rd, Bwaise Tc, Kazo, Nabweru Rd, Lugoba Kazinga, Mawanda Rd, East Nsooba, Kyebando, Tilupati Industrial Park, Mulago Hill, Turfnel Drive, Tagole Cresent, Kamwokya, Kubiri Gayaza Rd, Katanga, Wandegeya Byashara Street, Wandegaya Tc, Bombo Rd, Makerere University, Veterans Mkt, Mulago Hospital, Makerere Kavule, Makerere Kikumikikumi, Makerere Kikoni, Mulago, Nalweuba Zone Kampala East Sunday 4th October 2020 Jinja Industrial Walukuba 11kV Feeder Jinja Industrial 11kV feeders upgrade JINJA Walukuba Village Area, Masese, National Water Kampala East -

Health Sector Semi-Annual Monitoring Report FY2020/21

HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug MOFPED #DoingMore Health Sector: Semi-Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2020/21 A HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 MOFPED #DoingMore Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................................iv FOREWORD.........................................................................................................................vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY........................................................................................2 2.1 Scope ..................................................................................................................................2 2.2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................3 2.2.1 Sampling .........................................................................................................................3 -

Office of the Auditor General the Republic of Uganda

OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF MBALE REGIONAL REFERRAL HOSPITAL FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2016 Table of Contents LIST OF ACROYNMS ................................................................................................................................................. 2 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 5 2.0 AUDIT OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................................................................... 5 3.0 AUDIT PROCEDURES PERFORMED .......................................................................................................... 6 4.0 ENTITY FINANCING ..................................................................................................................................... 6 5.0 FINDINGS ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 5.1 Categorization of Findings ............................................................................................................................... 7 5.2 Summary of Findings ....................................................................................................................................... 7 6.0 DETAILED AUDIT FINDINGS .................................................................................................................... -

Facing Uganda's Law on Abortion

FACING UGANDA’S LAW ON ABORTION Experiences from Women & Service Providers July 2016 social justice in health I Foreword ganda’s law on abortion prohibits several acts and omissions relating to abortion and We need all of the help that we can get to reduce the prevalence of maternal mortality in Usets out to punish women and health workers who perform any of the prohibited acts. Uganda. With unsafe abortions contributing to over a quarter of all maternal mortality in And yet it should also be noted that every woman has a right to make decisions relating to Uganda, there is need to address the underlying factors that lead women into seeking unsafe her reproductive health and this decision includes the right to terminate or keep a pregnancy. abortions. Health workers need to operate in an environment without fear of being arrested This right can be read into the obligation of the state to provide medical services to the and harassed. In turn, women should be able to seek safe abortion services knowing that population, to enable women in exercising their full reproductive and maternal functions they will not suffer stigma or be punished for services they need. and the exception to the right to life that prescribes the development of a law that provides for instances in which a pregnancy may be terminated. Clarifying Uganda’s abortion law should be accompanied by the expansion of instances for which abortion can be accessed –such as cases of incest, rape, defilement and other Abortion affects girls, women, health workers, lawyers, police, and communities, with indications in which the health and life of the woman may be threatened. -

3Rd Annual Report 3.9.22.1248:3Rd Annual Report

The Power of Partnerships: The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief Third Annual Report to Congress The Power of Partnerships: The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief Third Annual Report to Congress Cover Photo Through HIV counseling and testing for couples at the U.S.-supported Kericho District Hospital, Joyce and David found out they are infected with HIV. Joyce was four months pregnant with her second child at the time of diagnosis. Thanks to the clinic’s program to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission, Joyce delivered a baby boy who is HIV-negative. After a year of antiretroviral treatment, David has also gained weight and feels healthy – enabling him to provide for his family. Photo by Doug Shaffer This report was prepared by the Office of the United States Global AIDS Coordinator in collaboration with the United States Departments of State (including the United States Agency for International Development), Defense, Commerce, Labor, Health and Human Services (including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the National Institutes of Health, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the Office of Global Health Affairs), and the Peace Corps. 2 ❚ The Power of Partnerships: The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief CONTENTS Acronyms and Abbreviations . 5 Overview – The Power of Partnerships . 9 Chapter 1 – Critical Intervention in the Focus Countries: Prevention. 27 Chapter 2 – Critical Intervention in the Focus Countries: Treatment . .55 Chapter 3 – Critical Intervention in the Focus Countries: Care . .79 Chapter 4 – Building Capacity: Partnerships for Sustainability .