Recommendations for Follow-Up After Colonoscopy and Polypectomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Number of Endometrial Polyps Is a Strong Predictor of Recurrence: findings of a Prospective Cohort Study in Reproductive-Age Women

ORIGINAL ARTICLE: GYNECOLOGY AND MENOPAUSE High number of endometrial polyps is a strong predictor of recurrence: findings of a prospective cohort study in reproductive-age women Fang Gu, M.D.,a Huanxiao Zhang, M.D.,b Simin Ruan, M.D.,c Jiamin Li, M.D.,d Xinyan Liu, M.D.,a Yanwen Xu, M.D.,a,e and Canquan Zhou, M.D.a,e a Center for Reproductive Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, b Division of Gynecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and c Department of Medical Ultrasonics, Institute of Diagnostic and Interventional Ultrasound, First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University; d Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical College; and e Key Laboratory of Reproductive Medicine of Guangdong Province, Guangzhou, People's Republic of China Objective: To compare the incidence of recurrence between a cohort with a high number (R6) of endometrial polyps (EPs) and a single- EP cohort among reproductive-age patients after polypectomy. Design: Prospective observational cohort study. Setting: Single university center. Patient(s): Premenopausal women who underwent hysteroscopic endometrial polypectomy were recruited. Intervention(s): Patients underwent a transvaginal ultrasound scan every 3 months after polypectomy to detect EP recurrence. Kaplan- Meier and Cox regression models were used to compare the risk of recurrence between the two cohorts and analyze the potential risk factors for EP recurrence. Main Outcome Measure(s): EP recurrence rate. Result(s): The study enrolled 101 cases with a high number of EP and 81 cases with a single EP. All baseline parameters were similar except that the high number of EP cohort had a slightly lower mean age than the single EP cohort (33.5 [range 30.0–39.0] vs. -

Guidelines for the Management of Hereditary Colorectal Cancer

Guidelines Guidelines for the management of hereditary Gut: first published as 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319915 on 28 November 2019. Downloaded from colorectal cancer from the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI)/ United Kingdom Cancer Genetics Group (UKCGG) Kevin J Monahan ,1,2 Nicola Bradshaw,3 Sunil Dolwani,4 Bianca Desouza,5 Malcolm G Dunlop,6 James E East,7,8 Mohammad Ilyas,9 Asha Kaur,10 Fiona Lalloo,11 Andrew Latchford,12 Matthew D Rutter ,13,14 Ian Tomlinson ,15,16 Huw J W Thomas,1,2 James Hill,11 Hereditary CRC guidelines eDelphi consensus group ► Additional material is ABSTRact having a family history of a first-degree relative published online only. To view Heritable factors account for approximately 35% of (FDR) or second degree relative (SDR) with CRC.2 please visit the journal online (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ colorectal cancer (CRC) risk, and almost 30% of the While highly penetrant syndromes such as Lynch gutjnl- 2019- 319915). population in the UK have a family history of CRC. syndrome (LS), familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) The quantification of an individual’s lifetime risk of and other polyposis syndromes account for account For numbered affiliations see end of article. gastrointestinal cancer may incorporate clinical and for only 5–10% of all CRC diagnoses, advances molecular data, and depends on accurate phenotypic in genetic diagnosis, improvements in endoscopic Correspondence to assessment and genetic diagnosis. In turn this may surgical control, and medical and lifestyle interven- Dr Kevin J Monahan, Family facilitate targeted risk-reducing interventions, including tions provide opportunities for CRC prevention and Cancer Clinic, St Mark’s endoscopic surveillance, preventative surgery and effective treatment in susceptible individuals. -

Polyp Classification from the Microscope

11/12/2019 OUTLINE Serrated lesions: • Updates on terminology Polyp classification from the • Updates on sessile serrated polyposis microscope HGD / intramucosal carcinoma / carcinoma in situ: • Clarify the terminology David F. Schaeffer, MD, FRCPC • Discuss diagnostic fears of pathologists Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, UBC The subtle polyp: Head, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Vancouver Coastal Health Pathology Lead, BCCA Colon Cancer Screening Program • Are some polyps really only hidden from the pathologist? • Do additional levels help? 3 January 2018 October 2019 OUTLINE WHY CARE ABOUT SERRATED POLYPS? Serrated lesions: FIT not useful • Updates on terminology • Updates on sessile serrated polyposis HGD / intramucosal carcinoma / carcinoma in situ: • Clarify the terminology • Discuss diagnostic fears of pathologists The subtle polyp: At best moderate • Are some polyps really only hidden from the agreement between pathologist? expert GI pathologist • Do additional levels help? October 2019 October 2019 1 11/12/2019 SIMPLIFIED VIEW OF SERRATED PATHWAY TYPES OF SERRATED POLYPS UNTIL JULY 2019 65% 30% 5% Important points Hyperplastic polyp (HP) Sessile Serrated Traditional Serrated • SSPs probably develop from MVHPs: MVHPs aren’t completely Microvesicular (MVHP) adenoma/polyp (SSA/P) Adenoma (TSA) innocuous but transformation to SSP is likely a rare event (occurs Goblet cell rich (GCHP ) more commonly in the right colon) • Serrated pathway is characterized by hypermethylation of -

ANMC Specialty Clinic Services

Cardiology Dermatology Diabetes Endocrinology Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) Gastroenterology General Medicine General Surgery HIV/Early Intervention Services Infectious Disease Liver Clinic Neurology Neurosurgery/Comprehensive Pain Management Oncology Ophthalmology Orthopedics Orthopedics – Back and Spine Podiatry Pulmonology Rheumatology Urology Cardiology • Cardiology • Adult transthoracic echocardiography • Ambulatory electrocardiology monitor interpretation • Cardioversion, electrical, elective • Central line placement and venous angiography • ECG interpretation, including signal average ECG • Infusion and management of Gp IIb/IIIa agents and thrombolytic agents and antithrombotic agents • Insertion and management of central venous catheters, pulmonary artery catheters, and arterial lines • Insertion and management of automatic implantable cardiac defibrillators • Insertion of permanent pacemaker, including single/dual chamber and biventricular • Interpretation of results of noninvasive testing relevant to arrhythmia diagnoses and treatment • Hemodynamic monitoring with balloon flotation devices • Non-invasive hemodynamic monitoring • Perform history and physical exam • Pericardiocentesis • Placement of temporary transvenous pacemaker • Pacemaker programming/reprogramming and interrogation • Stress echocardiography (exercise and pharmacologic stress) • Tilt table testing • Transcutaneous external pacemaker placement • Transthoracic 2D echocardiography, Doppler, and color flow Dermatology • Chemical face peels • Cryosurgery • Diagnosis -

3. Studies of Colorectal Cancer Screening

IARC HANDBOOKS COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING VOLUME 17 This publication represents the views and expert opinions of an IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Cancer-Preventive Strategies, which met in Lyon, 14–21 November 2017 LYON, FRANCE - 2019 IARC HANDBOOKS OF CANCER PREVENTION 3. STUDIES OF COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING 3.1 Methodological considerations end-point of the RCT can be the incidence of the cancer of interest. Methods for colorectal cancer (CRC) screen- The observed effect of screening in RCTs is ing include endoscopic methods and stool-based dependent on, among other things, the partic- tests for blood. The two primary end-points for ipation in the intervention group and the limi- endoscopic CRC screening are (i) finding cancer tation of contamination of the control group. at an early stage (secondary prevention) and Low participation biases the estimate of effect (ii) finding and removing precancerous lesions towards its no-effect value, and therefore it must (adenomatous polyps), to reduce the incidence be evaluated and reported. Screening of controls of CRC (primary prevention). The primary by services outside of the RCT also dilutes the end-point for stool-based tests is finding cancer effect of screening on CRC incidence and/or at an early stage. Stool-based tests also have some mortality. If the screening modality being eval- ability to detect adenomatous polyps; therefore, a uated is widely used in clinical practice in secondary end-point of these tests is reducing the the region or regions where the RCT is being incidence of CRC. conducted, then contamination may be consid- erable, although it may be difficult and/or costly 3.1.1 Randomized controlled trials of to estimate its extent. -

The Appropriate Time Interval Between Hysteroscopic Polypectomy and the Start of FET : a Retrospective Corchort Study

The Appropriate Time Interval Between Hysteroscopic Polypectomy and the Start of FET : A Retrospective Corchort Study Zhong-Kai Wang Zhengzhou University Third Hospital and Henan Province Women and Children's Hospital Hong-Wu Qiao Zhengzhou University Third Hospital and Henan Province Women and Children's Hospital She-Ling Wu Zhengzhou University Third Hospital and Henan Province Women and Children's Hospital Wen Zhang Zhengzhou University Third Hospital and Henan Province Women and Children's Hospital Xiao-Na Yu Zhengzhou University Third Hospital and Henan Province Women and Children's Hospital Jing Li Zhengzhou University Third Hospital and Henan Province Women and Children's Hospital Xing-Ling Wang Zhengzhou University Third Hospital and Henan Province Women and Children's Hospital Hua Lou Zhengzhou University Third Hospital and Henan Province Women and Children's Hospital Yi-Chun Guan ( [email protected] ) Zhengzhou University Third Hospital and Henan Province Women and Children's Hospital https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0312-3984 Research Keywords: Endometrial polyps, hysteroscopy, polypectomy, Frozen-embryo transfer, timing Posted Date: November 19th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-110131/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/14 Abstract Objective: To investigate when is the appropriate time interval between hysteroscopic polypectomy and the start of FET cycles Design: Retrospective cohort study. Setting: Academic center. Patient(s): All patients diagnosed with endometrial polyps undergoing hysteroscopic polypectomy before FET. Intervention(s): Hysteroscopic polypectomy. MainOutcomeMeasure(s): Patients were divided into four groups based on the time interval between hysteroscopic polypectomy and the start of FET Demographics, baseline FET characteristics, pregnancy outcomes after FET were compared among the groups. -

An “Expressionistic” Look at Serrated Precancerous Colorectal Lesions Giancarlo Marra

Marra Diagnostic Pathology (2021) 16:4 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-020-01064-1 RESEARCH Open Access An “expressionistic” look at serrated precancerous colorectal lesions Giancarlo Marra Abstract Background: Approximately 60% of colorectal cancer (CRC) precursor lesions are the genuinely-dysplastic conventional adenomas (cADNs). The others include hyperplastic polyps (HPs), sessile serrated lesions (SSL), and traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs), subtypes of a class of lesions collectively referred to as “serrated.” Endoscopic and histologic differentiation between cADNs and serrated lesions, and between serrated lesion subtypes can be difficult. Methods: We used in situ hybridization to verify the expression patterns in CRC precursors of 21 RNA molecules that appear to be promising differentiation markers on the basis of previous RNA sequencing studies. Results: SSLs could be clearly differentiated from cADNs by the expression patterns of 9 of the 12 RNAs tested for this purpose (VSIG1, ANXA10, ACHE, SEMG1, AQP5, LINC00520, ZIC5/2, FOXD1, NKD1). Expression patterns of all 9 in HPs were similar to those in SSLs. Nine putatively HP-specific RNAs were also investigated, but none could be confirmed as such: most (e.g., HOXD13 and HOXB13), proved instead to be markers of the normal mucosa in the distal colon and rectum, where most HPs arise. TSAs displayed mixed staining patterns reflecting the presence of serrated and dysplastic glands in the same lesion. Conclusions: Using a robust in situ hybridization protocol, we identified promising tissue-staining markers that, if validated in larger series of lesions, could facilitate more precise histologic classification of CRC precursors and, consequently, more tailored clinical follow-up of their carriers. -

Post-Polypectomy Colonoscopy Surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline – Update 2020

Guideline Post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline – Update 2020 Authors Cesare Hassan1, Giulio Antonelli1, Jean-Marc Dumonceau2, Jaroslaw Regula3, Michael Bretthauer4,Stanislas Chaussade5, Evelien Dekker6, Monika Ferlitsch7, Antonio Gimeno-Garcia8,RodrigoJover9,MetteKalager4,Maria Pellisé10,ChristianPox11, Luigi Ricciardiello12, Matthew Rutter13, Lise Mørkved Helsingen4, Arne Bleijenberg6,Carlo Senore14, Jeanin E. van Hooft6, Mario Dinis-Ribeiro15, Enrique Quintero8 Institutions 13 Gastroenterology, University Hospital of North Tees, 1 Gastroenterology Unit, Nuovo Regina Margherita Stockton-on-Tees, UK and Northern Institute for Hospital, Rome, Italy Cancer Research, Newcastle University, Newcastle 2 Gastroenterology Service, Hôpital Civil Marie Curie, upon Tyne, UK Charleroi, Belgium 14 Epidemiology and screening Unit – CPO, Città della 3 Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education and Maria Salute e della Scienza University Hospital, Turin, Italy Sklodowska-Curie Memorial Cancer Centre, Institute of 15 CIDES/CINTESIS, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oncology, Warsaw, Poland Porto, Porto, Portugal 4 Clinical Effectiveness Research Group, Oslo University Hospital and University of Oslo, Norway Bibliography 5 Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Unit, Faculté de DOI https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1185-3109 Médecine, Hôpital Cochin, Assistance Publique- Published online: 22.6.2020 | Endoscopy 2020; 52: 1–14 Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), Université Paris Descartes, © Georg Thieme Verlag -

NOAC-Doacs Perioperative Management

NOACS/DOACS*: PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OBJECTIVE: To provide guidance for the perioperative management of patients who are receiving a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) and require an elective surgery/procedure. For guidance on management of patients who require an urgent or emergency surgery/procedure, please refer to the Perioperative Anticoagulant Management Algorithm found on the Thrombosis Canada website under the “Tools” tab. BACKGROUND: Four DOACs (apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban and rivaroxaban) are approved for clinical use in Canada based on findings from large randomized trials. The perioperative management of DOAC-treated patients aims to interrupt anticoagulant therapy (if necessary) so there is no (or minimal) residual anticoagulant effect at the time of surgery, and to ensure timely but careful resumption after surgery so as to not incur an increased risk for post- operative bleeding. There are 3 important considerations for perioperative management of patients taking a DOAC: 1) Reliable laboratory tests to confirm the absence of a residual anticoagulant effect of DOACs are not widely available. 2) Half-lives of DOACs differ and increase with worsening renal function, affecting when the drug should be stopped before surgery. 3) DOACs have rapid onset of action, with a peak anticoagulant effect occurring 1-2 hours after oral intake. In the absence of laboratory tests to reliably measure their anticoagulant effect, the perioperative administration of DOACs should be influenced by: 1) Drug elimination half-life (with normal renal function), 2) Effect of renal function on drug elimination half-life 3) Bleeding risk associated with the type of surgery/procedure and anesthesia (Table 1) 4) Whether patient is to receive spinal/epidural anesthesia EVIDENCE SUPPORTING PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS TAKING A DOAC: There are emerging data relating to the efficacy and safety of the proposed perioperative management of DOAC-treated patients. -

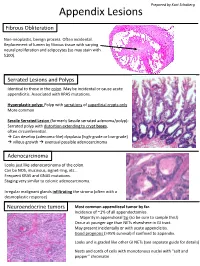

Appendix Lesions

Prepared by Kurt Schaberg Appendix Lesions Fibrous Obliteration Non-neoplastic, benign process. Often incidental. Replacement of lumen by fibrous tissue with varying neural proliferation and adipocytes (so may stain with S100). Serrated Lesions and Polyps Identical to those in the colon. May be incidental or cause acute appendicitis. Associated with KRAS mutations. Hyperplastic polyp: Polyp with serrations of superficial crypts only More common Sessile Serrated Lesion (formerly Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp): Serrated polyp with distortion extending to crypt bases, often circumferential. → Can develop (adenoma-like) dysplasia (high-grade or low-grade) → villous growth → eventual possible adenocarcinoma Adenocarcinoma Looks just like adenocarcinoma of the colon. Can be NOS, mucinous, signet-ring, etc… Frequent KRAS and GNAS mutations. Staging very similar to colonic adenocarcinoma. Irregular malignant glands infiltrating the stroma (often with a desmoplastic response) Neuroendocrine tumors Most common appendiceal tumor by far. Incidence of ~1% of all appendectomies. Majority in appendiceal tip (so be sure to sample this!) Occur at younger age than NETs elsewhere in GI tract. May present incidentally or with acute appendicitis. Good prognosis (>95% survival) if confined to appendix. Looks and is graded like other GI NETs (see separate guide for details) Nests and cords of cells with monotonous nuclei with “salt and pepper” chromatin Unique Appendiceal Lesions Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms Low-grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm (LAMN): -

Risks Associated with Anesthesia Services During Colonoscopy Karen J

Gastroenterology 2016;150:888–894 Risks Associated With Anesthesia Services During Colonoscopy Karen J. Wernli,1,2 Alison T. Brenner,2,3 Carolyn M. Rutter,1,4 and John M. Inadomi2,3 1Group Health Research Institute, Seattle, Washington; 2Department of Health Services, 3 CLINICAL AT Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington; 4RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity on page e18. Learning Objective: Upon completion of this test, successful learners will be able to (1) list colonoscopy complications associated with anesthesia instead of IV conscious sedation; (2) describe geographic diversity in use of anesthesia services in performance of colonoscopy; (3) describe polypectomy complications associated with use of anesthesia for colonoscopy. Keywords: Anesthesia Services; Endoscopy; Propofol; See editorial on page 801. Gastroenterology. Watch this article’s video abstract and others at http://bit.ly/1q51BlW. BACKGROUND & AIMS: We aimed to quantify the difference Scan the quick response (QR) code to the left with your mobile device to watch this article’s in complications from colonoscopy with vs without anes- video abstract and others. Don’t have a QR code thesia services. METHODS: We conducted a prospective reader? Get one by searching ‘QR Scanner’ in ’ cohort study and analyzed administrative claims data from your mobile device s app store. Truven Health Analytics MarketScan Research Databases from 2008 through 2011. We identified 3,168,228 colonoscopy procedures in men and women, aged 40–64 years old. Colo- noscopy complications were measured within 30 days, olonoscopy is the most common colorectal cancer including colonic (ie, perforation, hemorrhage, abdominal C screening test in the United States among average- 1 pain), anesthesia-associated (ie, pneumonia, infection, com- risk adults. -

Update on Polyp Surveillance Guidelines 2020

Update on Polyp Surveillance Guidelines 2020 Released 2020 health.govt.nz Citation: Ministry of Health. 2020. Update on Polyp Surveillance Guidelines. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Published in September 2020 by the Ministry of Health PO Box 5013, Wellington 6140, New Zealand ISBN 978-1-99-002937-0 (online) HP 7469 This document is available at health.govt.nz This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. In essence, you are free to: share ie, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format; adapt ie, remix, transform and build upon the material. You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the licence and indicate if changes were made. Contents Introduction 1 Purpose of this advice 3 Audience for these guidelines 3 Associated documents 4 Equity 4 Clinical advice 5 High-risk polyps 6 Notes on clinical context 6 Definitions 7 High-quality colonoscopy in New Zealand 7 Serrated polyposis syndrome 7 High-quality polypectomy 8 Multiple Adenoma referral criteria to the New Zealand Familial Gastrointestinal Cancer Service 8 Boston Bowel Preparation Scale 9 UPDATE ON POLYP SURVEILLANCE GUIDELINES iii Introduction Te Aho o Te Kahu (the Cancer Control Agency) in partnership with the National Screening Unit, Ministry of Health endorses this advice on surveillance colonoscopy for follow-up after removal of polyps. This advice sets out appropriate practice for clinicians to follow subject to their own judgement. It has been developed to help them make decisions in this area. The advice was developed to align with recent publications from the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia and Europe.1,2,3,4 These publications, based on updated available evidence up to June 2019, indicated that previous guidelines would now recommend over surveillance for some groups.