Due Process Considerations in State Unclaimed-Property Law Enforcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Getting and Nailing the Interview

LESSON TRANSCRIPT MODULE 2 | LESSON 2 GETTING AND NAILING THE INTERVIEW INTRO I can tell you from being on both sides of the job-seeking fence that not all job seekers are doing things to really stand out nail their interview. It’s important to not assume that employers will just magically know you’re awesome — you have to show them. Clip And no, I’m not going to necessarily tell you to get a pink scented résumé like Elle Woods, but it’s actually an awesome example of the kind of X-factor that you have to think about so that you can get plucked out of all the résumés on a potential employer’s desk. When I was first applying for my first job, I sent out hundreds of tapes all across the country to different news markets. And in local news, you start with the smallest and try © COPYRIGHT 2019 NICOLE LAPIN LESSON TRANSCRIPT to work your way up. I even tried to apply to national stations, I mean, the worst thing they could say was “no” and I felt pretty good knowing that at least I gave it a go. Wayne Gretzky said you miss 100% of chances you don’t take, right? But it was really the little touches that got me to get noticed. Back in the days of VHS, I know, I’m super old, applicants would send their tapes out with generic black sleeves and the label was just a sticker that they hand wrote their name on. I did not do that. -

NEWSLETTER October 2017 / Volume 20

NEWSLETTER October 2017 / Volume 20 Highlights Women and Finance, Part 2 Sandy Ashendorf, EVP of Content Distribution at EPIX joined us on September 6 to talk about Women in For part one, see our September newsletter here. Film. She shared these statistics with us about the number of women working in the film industry: Rewriting Your Money Script For many of us, our ideas and attitudes about money develop at an early age. Parents, teachers and Women Producers - 20.7% friends share long espoused phrases, like “Money is the root of all evil.” We’re taught that people are Women Screenwriters - 13.2% not merely rich, they are “filthy rich.” Society teaches us that understanding concepts, like investing, Women Directors - 4.1% retirement or taxes, is hard or boring. Worse yet, we may get the message that men are better at Women Composers - 1.7% finance or it is something that may only be interesting to men. Women Nominated for Best Director - 4 Having the Money Conversation Women Who Won Best Director - 1 (in 88 total nominations) So, how do we move past these ideas and attitudes? We have to start talking about money and To see more about Sandy’s talk, visit the blog here. talking about money can be scary for many people. Talking about finances is, typically, considered impolite in Western culture. People will discuss almost any other topic, whether that’s marriage, sex, religion or politics, but not money. We can take small steps towards starting that dialogue. We can Upcoming Events talk with our spouse or significant other and share fears, goals and plan together with our partner. -

In a Multivu Minute – April 2019

IN A MULTIVU MINUTE A MEDIA RELATIONS & DistriBUTION BULLETIN APRIL 2019 IN A MULTIVU MINUTE A MEDIA RELATIONS & DISTRIBUTION BULLETIN SMT SPOTLIGHT Photo credit: MultiVu NCBA Chuck Knows Beef App Launch SMT March 20th The National Cattlemen’s Beef Association recently launched their new AI tool – Chuck Knows Beef. To highlight the launch and provide consumers with tips and resources when cooking with beef, we executed a media tour along with a Multichannel News Release and National and local market TV placements. We conducted the SMT from the NCBA’s Culinary Center in Denver, CO and procured local chef Jennifer Jasinski to be our spokesperson. In addition to securing 29 bookings, our video aired on DirecTV’s lifestyle networks and on GMA Weekend in New York City, Chicago, Dallas & CBS this Morning in Los Angeles and Philadelphia. IN A MULTIVU MINUTE A MEDIA RELATIONS & DISTRIBUTION BULLETIN SMT SPOTLIGHT Great response from stations, including a TV producer from St. Louis who said “I loved all the ‘show and tell’!” IN A MULTIVU MINUTE A MEDIA RELATIONS & DISTRIBUTION BULLETIN SMT SPOTLIGHT Photo credit: MultiVu Facebook Live for TaxSlayer! April 2nd With April 15th just around the corner, our client Taxslayer wanted a clever way to reach consumers and tax filers. The Media Relations team brainstormed ideas and came up with a fun visual aspect: adding a carnival-style wheel to the segment with tax topics listed on it. MultiVu Producer Paulina Gerzon, serving as the moderator, asked financial expert, Nicole Lapin, questions pertaining to the topic the arrow landed on. The result was a lively and engaging twenty minute segment. -

Financial, Business and General Media Email Distribution

Financial, Business and General Media Email Distribution Title Title A Connecticut Law Blog IQ (Insider Quarterly) (2) A Dash of Insight IR Magazine (6) A Diary of Injustice in Scotland IR Magazine - London Bureau (2) A Georgia Lawyer IR Magazine - New York Bureau (2) A Passion for Research IR Update a public defender IranContact A Spokesman Said Iravunk A-Team Group - Risk-Technology.net Ireland Business Insider A.M. Best Europe (2) Ireson, Nelson A&B Blawg Briefs iRights.info AAHOA Lodging Business Irish Examiner AAII Journal (2) Irish Examiner - Business Desk AAII Journal Online Irish Examiner - Freelancers AARP Irish Examiner - irishexaminer.com AARP Bulletin Today (3) Irish Examiner - Picture Desk AARP The Magazine (4) Irish Examiner - Property AARP.com Blog Irish Examiner - Sports Desk AARP.org Irish News - Business Desk, The ABA Journal Irish News, The ABA Journal Online Irish Pharmacist ABA Trust Letter Is4profit.com (2) ABA Washington Letter, The Isabel Winklbauer ABA Washington Summary iSave A2Z Abbamonte, Lee ISCOTUS - blogs kentlaw ABC Magazine (Sussex) ISDA (2) ABC News Radio Network ISDA - USA, New York Bureau ABC Television Network (2) Iskra abfjournal (3) Islamic Finance Information Service ABI Journal (2) Islamic Law and Society ABL Advisor (3) Islamic Law In Our Times ABLawg ISO Management Aboriginal Law Blog ISOS About.com (5) israelinfo.co.il Above The Law Issues in Accounting Education Above the Market IST Magazine Absolute Return IStR - Internationales Steuerrecht Absolute UCITS (2) Isurus (2) ACC Docket IT Europa -

Journalism Awards

FORTY-NINTH 4ANNUAL 9SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB th Congratulations 49 Annual Awards for Editorial Southern California Journalism Awards Excellence in 2006 David Glovin and David Evans and Los Angeles Press Club Finalist: Magazines/Investigative A non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status Tax ID 01-0761875 Honorary Awards “How Test Companies Fail Your Kids” 4773 Hollywood Boulevard Bloomberg Markets, December 2006 Hollywood, California 90027 for 2007 Phone: (323) 669-8081 Fax: (323) 669-8069 David Glovin and David Evans Internet: www.lapressclub.org E-mail: [email protected] THE PRESIDENT’S AWARD Finalist: Investigative Series For Impact on Media “SATs Scored in Error by Test Companies Roil Admissions Process” PRESS CLUB OFFICERS Gustavo Arellano PRESIDENT: Anthea Raymond “Ask a Mexican” Radio reporter/editor OC Weekly VICE PRESIDENT: Ezra Palmer Seth Lubove Yahoo! News THE DANIEL PEARL Award Finalist: Entertainment Feature TREASURER: Rory Johnston Freelance For Courage and Integrity in Journalism 3 “John Davis, Marvin’s Son, Feuds With Sister Over ‘Looted’ Fund” SECRETARY: Jon Beaupre Radio/TV journalist, Educator Anna Politkovskaya EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Diana Ljungaeus Journalist Chet Currier International Journalist Novaya Gazeta Finalist: Column/Commentary BOARD MEMBERS Jahan Hassan, Ekush (Bengali newspaper) THE JOSEPH M. QUINN Award Josh Kleinbaum, Los Angeles Newspaper Group For Journalistic Excellence and Distinction Michael Collins, EnviroReporter.com Eric Longabardi, TeleMedia News Prod. -

Fall 2019 Benbella Books

BenBella Books: Fall 2019 BenBella Books 16 YEARS OF INNOVATIVE PUBLISHING BENBELLABOOKS.COM FALL 2019 CATALOG Twitter: @BenBellaBooks Facebook: /BenBellaBooks SMARTPOPBOOKS.COM Twitter: @SmartPopBooks Facebook: /SmartPopBooks Letter from the publisher HELLO THERE! DEAR READER, 1 How many times have you unconsciously checked your phone today after hearing the tell-tale “ping” of a notification? When’s the last time you were immersed in a project at work, only to be interrupted by an email alert? Technology gets a bad rap for being the cause of these constant distractions, but the truth is, technology’s not the problem—we are. From the bestselling author of Hooked, Nir Eyal’s Indistractable sheds light on why we’re so susceptible to distractions and provides science-backed advice to show how we can overcome them. Legendary artist Neil Young has a bone to pick with the way the music industry is providing us with music. CDs, MP3s, and low-quality streaming services have largely replaced high-quality analog sound. The lifeless audio we’re used to hearing is a far cry from how artists intend for it to sound. In To Feel the Music, Neil, along with coauthor Phil Baker, lays out his mission to bring back high-quality audio—from the Pono music player to the Neil Young Archives—overcoming setbacks and skeptics to deliver music the way it was meant to be heard. You’ve likely heard of Zappos, the online retailer known for its innovative approach to business, radical focus on company culture, above-and-beyond customer service, and fearless CEO Tony Hsieh, author of Delivering Happiness. -

Myth of the Immobile American - CNBC 6/3/11 5:20 PM

Myth of the Immobile American - CNBC 6/3/11 5:20 PM Symbol Symbol / Company Lookup Welcome, Guest HOME NEWS MARKETS EARNINGS INVESTING VIDEO CNBC TV CNBC 360 CNBC PRO Register Sign In U.S. ASIA-PACIFIC EUROPE ECONOMY ENERGY GREEN TECHNOLOGY BLOGS WIRES SLIDESHOWS SPECIAL REPORTS CORRECTIONS Sometimes the Can Kicks You. Myth of the Immobile American Email: [email protected] Call: 201-735-iNet (4638) Published: Wednesday, 20 Apr 2011 | 1:43 PM ET Text Size Text Message: Text NETNET followed by your tip to 26221. By: John Carney Senior Editor, CNBC.com Recommend Twitter LinkedIn Americans supposedly cannot move to fill new job openings because they are stranded by the ongoing housing slump. Its a story familiar to many. But it may not be true. The myth the housing crash had created a Getty Images sudden plunge in American mobility got started when the Census Bureau released statistics that appeared to show that the number of people who changed residences declined dramatically from March 2007 to March 2008. “Look at the economy, look at the banking industry, look at the credit industry. People cant move, what are they going to do? Their homes are now worth less than what they originally paid, and they don want to take a loss,” Patrick Bonnema, sales manager for Anderson Brothers Moving and Storage in SAC Wins Again! Chicago, told the New York Times in 2009. The Ancient and Noble Greek Tradition of Debt Repudiation Can Groupon Really Reduce Its Marketing Costs? A new study from the Minneapolis Fed, however, says that this sudden plunge The Real Story Behind the Latest Mark Zuckerberg Scandal is a statistical illusion. -

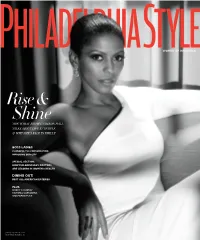

Philadelphia Style 2015, Issue 2 Late Spring Tamron Hall CHANGING the CONVERSATION

philadelphia style ® 2015, 2015, i ssue 2 ssue Women of Influence Rise & late spring late Shine THE TODAY SHOW’S TAMRON HALL TALKS ABOUT LIFE AT TEMPLE & WHy SHE’S BAcK IN PHILLy boss ladies changing the conversation, improving our city special section: hoW philadelphia’s DOCTORS are leading in Women’s HEALTH dining out! BEST all-american EATERIES PLUS D’Arcy F. ruDnAy VictoriA cArtAgenA WolFgAng Puck tamron hall tamron phillystylemag.com NICHE MEDIA HOLDINGS, LLC CHANGING the CONVERSATION We see them on television and read about them in headlines— but while they are breaking news, they are often making news of their own. Meet the seven women who are effecting positive change in Philadelphia right now, from education reform and personal finance to sustainability programs. As told to SARAH JORDAN Photography by BILLY ROOD On the Map MERYL LEVITZ As president and CEO of Visit Philadelphia, the marketing agency behind successful campaigns such as “Philly’s More Fun When You Sleep Over” and “Philadelphia—Keep Your History Straight and Your Nightlife Gay,” Levitz is a seasoned veteran who’s busy rebranding Philly into one of the hottest destinations in the world. My First Job: I was a sales clerk in a department store in Chicago, selling menswear and something we called “record albums” back then. On Starting Out: I was teaching continuing education courses [in time management and money management] at the Philadelphia College of Art, now the University of the Arts, and one thing led to another—and here I am at Visit Philly. On Entertaining Out-of-Towners: There are so many choices, and there is something for everyone. -

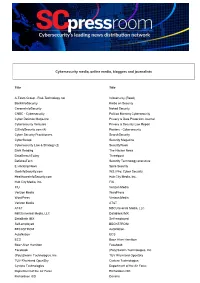

Cybersecurity Media, Online Media, Bloggers and Journalists

Cybersecurity media, online media, bloggers and journalists Title Title A-Team Group - Risk-Technology.net Infosecurity (Reed) BankInfoSecurity Krebs on Security CareersInfoSecurity Naked Security CNBC - Cybersecurity Politico Morning Cybersecurity Cyber Defence Magazine Privacy & Data Protection Journal Cybersecurity Ventures Privacy & Security Law Report CUInfoSecurity.com (4) Reuters - Cybersecurity Cyber Security Practitioners SearchSecurity CyberScoop Security Magazine Cybersecurity Law & Strategy (2) SecurityWeek Dark Reading The Hacker News DataBreachToday Threatpost DefenseTech Security Technology executive E Hacking News Spire Security GovInfoSecurity.com WSJ Pro: Cyber Security HealthcareInfoSecurity.com Hub City Media, Inc. Hub City Media, Inc. FIU FIU Verizon Media Verizon Media WordPress WordPress Verizon Media Verizon Media AT&T AT&T NBCUniversal Media, LLC NBCUniversal Media, LLC DataBank IMX DataBank IMX Self-employed Self-employed BECKSTROM BECKSTROM AutoNation AutoNation ECS ECS Booz Allen Hamilton Booz Allen Hamilton Facebook Facebook (Poly)Swarm Technologies, Inc. (Poly)Swarm Technologies, Inc. TUV Rheinland OpenSky TUV Rheinland OpenSky Cyxtera Technologies Cyxtera Technologies Department of the Air Force Department of the Air Force Richardson ISD Richardson ISD Dansha Dansha Prime Tech Partners Prime Tech Partners LookingGlass Cyber Solutions, Inc. LookingGlass Cyber Solutions, Inc. DataBlockChain DataBlockChain Knowledge Accelerators Knowledge Accelerators Transmosis Transmosis SpliceNet SpliceNet Protocol Labs -

Winnie Phan - Young People Who Rock - CNN.Com Blogs 4/13/09 5:37 PM

Winnie Phan - Young People Who Rock - CNN.com Blogs 4/13/09 5:37 PM My Account My Dashboard New Post Blog Info → HOME WORLD U.S. POLITICS CRIME ENTERTAINMENT HEALTH TECH TRAVEL LIVING BUSINESS SPORTS TIME.COM CNN VIDEO IREPORT RSS FEEDS Hot Topics » Phil Spector • Money & Main St. • Thailand • Pirates • Crime • Commentary • more topics » Weather Forecast International Edition March 29, 2009 About this blog Winnie Phan Young People Who Rock is a weekly Posted: 03:25 PM ET interview series focused on people under 30 — from CEOs to entertainers to Winnie Phan grew up in a troubled home. Her athletes to community and political parents didn’t support her education or give her the leaders — who are doing remarkable opportunities other kids her age enjoyed. By the things. Nicole Lapin finds them and time she managed to make it through grade introduces them here by writing a weekly school, she was on the road to becoming a column that goes out in time for you to statistic. chime in before she interviews them California has a 25% high school dropout rate, Fridays on CNN.com Live. according to the California Board of Education. Watch a video explainer Nationwide, the dropout rate is about 31%. Winnie, now a junior, is determined to defy the statistic herself and inspire her contemporaries to do the same. Winnie started Safe Walks in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco, pairing up older kids with Winnie Phan, 16, educates kids on the importance of younger kids to make sure that everyone gets to staying in school. -

The Occupation of Alcatraz (1969): Occupation, Legislation, and Sensation” Angela Coco ’19 [email protected] Winner: 2018 Hersey Prize

“The Occupation of Alcatraz (1969): Occupation, Legislation, and Sensation” Angela Coco ’19 [email protected] Winner: 2018 Hersey Prize When eighty-nine American Indians set out to occupy Alcatraz Island in the early morning hours of November 20, 1969, they had little idea that their symbolic occupation would be, not only a huge step for the “Red Power” movement, but also a propellent of Native desires to the forefront of American policy. In Part One, this essay will describe the occupation’s inciting incidents, the event itself, the motivations of several key players, and the media reaction. In Part Two, this essay will highlight positive legislation that came about as a result of the occupation. In Part Three, this essay will explore the occupation’s profound impact on the Red Power movement, as well as address the argument that the occupation did not have a very far reaching impact at all. This essay will conclude that, in the wake of their boats, these eighty-nine Native Indians left an ultimately positive impact on the lives of Native people for years to come. Part One: Occupation The Occupation of Alcatraz Island lasted fourteen months from November 20, 1969 to June 11, 1971. However, the first incidents involving Alcatraz Island actually started five years earlier. In 1964, a small group of Sioux occupied the island for four hours, claiming that Alcatraz should be owned by the collective Indian.1 Unfortunately, this protest was short lived. The occupiers left under threat that they would be charged with a felony.2 After this first “occupation,” community leader Adam Nordwall, also known as Adam Fortunate Eagle, and Mohawk Richard Oakes, a student 1 Adam Fortunate Eagle, Alcatraz! Alcatraz! The Indian Occupation of 1969–1971 (Heyday Books, 1992), 15. -

Christine Brennan Michael Wilbon \

CHRISTINE BRENNAN MICHAEL WILBON TALK SPORTS CAREERS AND MEDILL \ THE INS AND OUTS INSIDE MEDILL’S SPORTS MEDIA SPECIALIZATION \ IRA BERKOW ON BASEBALL \ DESTINATION: DENVER FOUR ALUMS INSPIRED BY THE FALL 2015 \ ISSUE 91 \ ALUMNI MAGAZINE MILE-HIGH CITY J'nelle Agee (MSJ15) and Joe Musso (MSJ15) pose next to a replica of the original ESPN sign from the network's debut in 1979. Photo by Marc Zarefsky 2016 marks the 50th anniversary of Medill’s Washington Program and we need your help! The winter 2016 issue of the Medill magazine will feature stories, images and anecdotes from Medill Washington program alumni and 14 24 30 faculty. If you participated in Medill’s GOING BEYOND The Science Writer A New Washington program during your THE BOX SCORE Benedict Carey — author and Biography: time at Medill, we want to hear from A look inside the Medill Sports a New York Times science and John Bartlow Media Specialization. you! Send us your images, clips, medical reporter — on finding his Martin videos, fondest memories, musings COVER PHOTO BY MARC ZAREFSKY (BSJ07) writing niche. An interview with author Ray or anything you think might 26 Boomhower on Martin’s life contribute well to this special 10 The Reunion as a diplomat and teacher at Medill. celebration. Please include detailed Destination: Denver Essayist Ellen Blum Barish captions for accuracy. uncovers a story from a long- 32 Four alumni and their careers as forgotten memory. storytellers in the Colorado capital. Class Note: Ira Berkow Stay tuned for dates EMAIL: [email protected] 28 Defining moments and times for various 18 Making Causes in the sportswriter’s SNAIL MAIL: Belinda Clarke Washington program The Q&A 1845 Sheridan Road, Count career and his latest book on Wrigley Field.