Department of the Interior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Species Accepted –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Swinhoe’S Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma Monorhis )

his is the 20th published report of the ABA Checklist Committee (hereafter, TCLC), covering the period July 2008– July 2009. There were no changes to commit - tee membership since our previous report (Pranty et al. 2008). Kevin Zimmer has been elected to serve his second term (to expire at the end of 2012), and Bill Pranty has been reelected to serve as Chair for a fourth year. During the preceding 13 months, the CLC final - ized votes on five species. Four species were accepted and added to the ABA Checklist , while one species was removed. The number of accepted species on the ABA Checklist is increased to 960. In January 2009, the seventh edition of the ABA Checklist (Pranty et al. 2009) was published. Each species is numbered from 1 (Black-bellied Whistling-Duck) to 957 (Eurasian Tree Sparrow); ancillary numbers will be inserted for all new species, and these numbers will be included in our annual reports. Production of the seventh edi - tion of the ABA Checklist occupied much of Pranty’s and Dunn’s time during the period, and this com - mitment helps to explain the relative paucity of votes during 2008–2009 compared to our other recent an - nual reports. New Species Accepted –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Swinhoe’s Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma monorhis ). ABA CLC Record #2009-02. One individual, thought to be a juvenile in slightly worn plumage, in the At - lantic Ocean at 3 4°5 7’ N, 7 5°0 5’ W, approximately 65 kilometers east-southeast of Hatteras Inlet, Cape Hat - teras, North Carolina on 2 June 2008. -

Geographic Variation in Leach's Storm-Petrel

GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION IN LEACH'S STORM-PETREL DAVID G. AINLEY Point Reyes Bird Observatory, 4990 State Route 1, Stinson Beach, California 94970 USA ABSTRACT.-•A total of 678 specimens of Leach's Storm-Petrels (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) from known nestinglocalities was examined, and 514 were measured. Rump color, classifiedon a scale of 1-11 by comparison with a seriesof reference specimens,varied geographicallybut was found to be a poor character on which to base taxonomic definitions. Significant differences in five size charactersindicated that the presentlyaccepted, but rather confusing,taxonomy should be altered: (1) O. l. beali, O. l. willetti, and O. l. chapmani should be merged into O. l. leucorhoa;(2) O. l. socorroensisshould refer only to the summer breeding population on Guadalupe Island; and (3) the winter breeding Guadalupe population should be recognizedas a "new" subspecies,based on physiological,morphological, and vocal characters,with the proposedname O. l. cheimomnestes. The clinal and continuoussize variation in this speciesis related to oceanographicclimate, length of migration, mobility during the nesting season,and distancesbetween nesting islands. Why oceanitidsfrequenting nearshore waters during nestingare darker rumped than thoseoffshore remains an unanswered question, as does the more basic question of why rump color varies geographicallyin this species.Received 15 November 1979, accepted5 July 1980. DURING field studies of Leach's Storm-Petrels (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) nesting on Southeast Farallon Island, California in 1972 and 1973 (see Ainley et al. 1974, Ainley et al. 1976), several birds were captured that had dark or almost completely dark rumps. The subspecificidentity of the Farallon population, which at that time was O. -

The Cycle of the Common Loon (Brochure)

ADIRONDACK LOONS AND LAKES FOR MORE INFORMATION: NEED YOUR HELP! lthough the Adirondack Park provides A suitable habitat for breeding loons, the summering population in the Park still faces many challenges. YOU CAN HELP! WCS’ Adirondack Loon Conservation Program Keep Shorelines Natural: Help maintain ~The Cycle of the this critical habitat for nesting wildlife and 7 Brandy Brook Ave, Suite 204 for the quality of our lake water. Saranac Lake, NY 12983 Common Loon~ (518) 891-8872, [email protected] Out on a Lake? Keep your distance (~100 feet or more) from loons and other wildlife, www.wcs.org/adirondackloons so that you do not disturb them. The Wildlife Conservation Society’s Adirondack Going Fishing? Loon Conservation Program is dedicated to ∗ Use Non-Lead Fishing Sinkers and improving the overall health of the environment, Jigs. Lead fishing tackle is poisonous to particularly the protection of air and water loons and other wildlife when quality, through collaborative research and accidentally ingested. education efforts focusing on the natural history ∗ Pack Out Your Line. Invisible in the of the Common Loon (Gavia immer) and water, lost or cut fishing line can conservation issues affecting loon populations entangle loons and other wildlife, often and their aquatic habitats. with fatal results. THE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION SOCIETY IS Be an Environmentally Wise Consumer: GRATEFUL TO ITS COLLABORATORS FOR THEIR Many forms of environmental pollution SUPPORT OF THE LOON PROGRAM: result from the incineration of fossil Natural History Museum of the Adirondacks - fuels, primarily from coal-fired power The W!ld Center plants and vehicles, negatively affecting www.wildcenter.org A guide to the seasonal Adirondack ecosystems and their wild NYS Dept. -

2010 FINAL MAMU Reportav

Summary of 2010 Marbled Murrelet Monitoring Surveys In the Santa Cruz Mountains Prepared For: Department of Parks and Recreation Santa Cruz District 303 Big Trees Park Road Felton CA, 95018 Prepared By: Brian Shaw Klamath Wildlife Resources 1760 Kenyon Drive Redding, CA 96001 12/31/2010 Edited for clarity, organization and content by: Portia Halbert ES for California State Parks 12/19/2014 INTRODUCTION This report covers the results of Marbled Murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus) monitoring surveys completed in 2010 for the Santa Cruz District of California State Parks, and is the first of a three-year monitoring effort for the seabird. The surveys took place at Big Basin Redwoods State Park, Portola Redwoods State Park, Butano State Park and San Mateo County Memorial Park. These surveys are carried out in support of and to follow-up data gathered by previous similar studies completed in the Santa Cruz Mountains from years back as far as 1992. It also continues an ongoing effort to study murrelet populations after the Command oil spill that occurred in 1988. METHODOLOGY In previous years, California Department of Fish and Game (DFG) has funded this work; at Portola and Big Basin since 1992 and 1995. At Portola, monitoring years included 1992- 1995, 1998, as well as in 2001-2003 and included only one murrelet observation station. The study has been carried out at Big Basin at five survey stations over the years of 1995-1996, 1998, and 2001-2003. During the 1995-1996, and 1998 the monitoring at Big Basin consisted of five surveys at each station during the protocol period. -

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

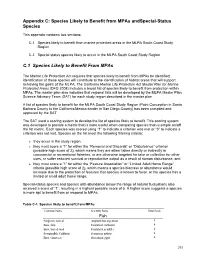

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2015 Contents

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2015 Contents ABOUT THE REPORT 1 HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT 52 Key themes and aspects of information disclosure 2 Goals and results of activities Significant themes and aspects of the 2015 Report 3 to develop human resource potential in 2015 54 Employee demographics 56 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 4 HR management system 57 Employer brand 59 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE MANAGEMENT BOARD 6 Remuneration and social support for personnel 60 Cooperation with trade unions 62 ABOUT THE COMPANY 8 Personnel training and development 62 Mission 10 Development of the talent pool 67 Gazprom Neft values 10 Work with graduates and young professionals 68 Strategic goal 10 Goals for 2016 69 Core businesses and structure of Company 11 Geography of operations 12 SAFE DEVELOPMENT: INDUSTRIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL SAFETY, Gazprom Neft in 2015: OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY, ENERGY EFFICIENCY key financial and production results 13 AND ENERGY CONSERVATION 70 Policy and management 72 ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE AND INNOVATIVE DEVELOPMENT 14 Supply chain responsibility 75 Exploration and production 16 Stakeholder engagement 76 Oil refining 18 Industrial safety and occupational health and safety 78 Sale of oil and petroleum products 19 Goals and results of industrial and occupational Sale of petroleum products by the filling safety activities in 2015 80 station network and by product business units 20 Mitigating the negative environmental impact Petrochemistry 23 and the effective use of resources 82 Innovation 24 -

Pacific Loon

Pacific Loon (Gavia pacifica) Vulnerability: Presumed Stable Confidence: Moderate The Pacific Loon is the most common breeding loon in Arctic Alaska, nesting throughout much of the state (Russell 2002). This species typically breeds on lakes that are ≥1 ha in size in both boreal and tundra habitats. They are primarily piscivorous although they are known to commonly feed chicks invertebrates (D. Rizzolo and J. Schmutz, unpublished data). Many Pacific Loons spend their winters in offshore waters of the west coast of Canada and the U.S. (Russell 2002). The most recent Alaska population estimate is 100-125,000 individuals (Ruggles and Tankersley 1992) with ~ 69,500 on the Arctic Coastal Plain specifically (Groves et al. 1996). encroachment (Tape et al. 2006) into tundra habitats. Although small fish make up a significant part of the Pacific Loon diet, they also eat many invertebrates (e.g., caddis fly larvae, nostracods) and so, unlike some other loon species, exhibit enough flexibility in their diet that they would likely be able to adjust to climate-mediated changes in prey base. S. Zack @ WCS Range: We used the extant NatureServe map for the assessment as it matched other range map sources and descriptions (Johnson and Herter 1989, Russell 2002). Physiological Hydro Niche: Among the indirect exposure and sensitivity factors in the assessment (see table on next page), Pacific Loons ranked neutral in most categories with the exception of physiological hydrologic niche for which they were evaluated to have a “slightly to greatly increased” vulnerability. This response was driven primarily by this species reliance on small water bodies (typically <1ha) for breeding Disturbance Regime: Climate-mediated and foraging. -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species 02 05 Restore Canada Jay as the English name of Perisoreus canadensis 03 13 Recognize two genera in Stercorariidae 04 15 Split Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) into two species 05 19 Split Pseudobulweria from Pterodroma 06 25 Add Tadorna tadorna (Common Shelduck) to the Checklist 07 27 Add three species to the U.S. list 08 29 Change the English names of the two species of Gallinula that occur in our area 09 32 Change the English name of Leistes militaris to Red-breasted Meadowlark 10 35 Revise generic assignments of woodpeckers of the genus Picoides 11 39 Split the storm-petrels (Hydrobatidae) into two families 1 2018-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 280 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species Effect on NACC: This proposal would change the species circumscription of Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus by splitting it into four species. The form that occurs in the NACC area is nominate pacificus, so the current species account would remain unchanged except for the distributional statement and notes. Background: The Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus was until recently (e.g., Chantler 1999, 2000) considered to consist of four subspecies: pacificus, kanoi, cooki, and leuconyx. Nominate pacificus is highly migratory, breeding from Siberia south to northern China and Japan, and wintering in Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The other subspecies are either residents or short distance migrants: kanoi, which breeds from Taiwan west to SE Tibet and appears to winter as far south as southeast Asia. -

Summary of 2010 Marbled Murrelet Monitoring Surveys in the Santa Cruz Mountains

Summary of 2010 Marbled Murrelet Monitoring Surveys In the Santa Cruz Mountains Prepared For: Department of Parks and Recreation Santa Cruz District 303 Big Trees Park Road Felton CA, 95018 Prepared By: Brian Shaw Klamath Wildlife Resources 1760 Kenyon Drive Redding, CA 96001 12/31/2010 INTRODUCTION This report covers the results of Marbled Murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus) monitoring surveys completed in 2010 for the Santa Cruz District of the California State Parks, and is the first of a three-year monitoring effort for the seabird. The surveys took place at Big Trees State Park, Portola Redwood State Park, Butano State Park and San Mateo County Memorial Park. These surveys are carried out in support of and to follow-up similar data taken by previous similar studies completed here in the during 2003 and in previous years. It also continues an ongoing effort to study murrelet populations after the oil spill that occurred nearby in 1988. METHODOLOGY In previous years, California Department of Fish and Game (DFG) has funded this work; at Portola and Big Basin since 1992 and 1995. At Portola, monitoring years included 1992- 1995, 1998, as well as in 2001-2003 and included only one murrelet observation station. The study has been carried out at Big Basin at five survey stations over the years of 1995-1996, 1998, and 2001-2003. During the 1995-1996, and 1998 the monitoring at Big Basin consisted of five surveys at each station during the protocol period. Coverage was minimized during the 2001-2003 years, with just three surveys annually completed at each observing station from mid-June to late-July, with two in July. -

Gazprom EE 2014 11.Indd

OAO Gazprom Environmental Report 2014 The Power of Growth OAO Gazprom Environmental Report 2014 Table of contents 5 Letter of Deputy Chairman of OAO Gazprom Management Committee 6 Introduction 8 Environmental protection management 8 Environmental Management System 11 Environmental targets and programs 13 Financing of environmental protection 16 Adverse environmental impact fee 20 Environmental performance and energy saving 20 Air protection 24 Greenhouse gas emissions 25 Utilization of associated petroleum gas 27 Reduction of vehicle fl eet impact on air 29 Water use and protection of water resources 31 Production and consumption waste management 36 Protection of land and soil 40 Protection of biodiversity 43 Energy saving 46 Parameters of environmental activity and environmental impact of OAO Gazprom abroad 48 Preventing negative impact on the environment 48 Environmental assessment of projects 50 Production environmental monitoring and control 56 Accidents and incidents 57 Environmental risks insurance 58 State environmental control 59 Environment protection scientifi c and technical support 59 Scientifi c research and development 64 Implementation of the best available technologies for environmental protection 65 Gazprom Prize in science and technical engineering 67 International cooperation 69 Information disclosure 71 Major results of Year of Environmental Awareness in OAO Gazprom 74 Offi cial events of OAO Gazprom 77 Events of subsidiary companies 84 Conclusion 85 Glossary of main terms and abbreviations 87 Addresses and contacts OAO Gazprom Environmental Report 2014 Letter of Deputy Chairman of 5 OAO Gazprom Management Committee Dear readers! On behalf of the OAO Gazprom Management Committee I present you our Environmental Report 2014. In the Gazprom strategy as both socially responsible and power industry company, we pay special attention to the issues of preservation of nature, environmental protection and energy saving. -

Loons: Wildlife Notebook Series

Loons Loons are known as “spirits of the wilderness,” and it is fitting that Alaska has all five species of loons found in the world. Loons are an integral part of Alaska's wilderness—a living symbol of Alaska's clean water and high level of environmental quality. Loons, especially common loons, are most famous for their call. The cry of a loon piercing the summer twilight is one of the most thrilling sounds of nature. The sight or sound of one of these birds in Alaskan waters gives a special meaning to many, as if it were certifying the surrounding as a truly wild place. Description: Loons have stout bodies, long necks, pointed bills, three-toed webbed feet, and spend most of their time afloat. Loons are sometimes confused with cormorants, mergansers, grebes, and other diving water birds. Loons have solid bones, and compress the air out of their feathers to float low in the water. A loon's bill is held parallel to the water, but the cormorant holds its hooked bill at an angle. Mergansers have narrower bills and a crest. Grebes, also diving water birds, are relatively short-bodied. Loons can be distinguished from ducks in flight by their slower wing beat and low-slung necks and heads. The five species of loons found in Alaska are the common, yellow-billed, red-throated, pacific and arctic. Common loons (Gavia immer), have deep black or dark green heads and necks and dark backs with an intricate pattern of black and white stripes, spots, squares, and rectangles. The yellow-billed loon (Gavia adamsii) is similar, but it has white spots on its back and a straw-yellow bill even in winter.