Neoliberal Capitalism in Crisis: Solutions from Confucius, Gandhi, and Psychological Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friends of Gandhi

FRIENDS OF GANDHI Correspondence of Mahatma Gandhi with Esther Færing (Menon), Anne Marie Petersen and Ellen Hørup Edited by E.S. Reddy and Holger Terp Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum, Berlin The Danish Peace Academy, Copenhagen Copyright 2006 by Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum, Berlin, and The Danish Peace Academy, Copenhagen. Copyright for all Mahatma Gandhi texts: Navajivan Trust, Ahmedabad, India (with gratitude to Mr. Jitendra Desai). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transacted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum: http://home.snafu.de/mkgandhi The Danish Peace Academy: http://www.fredsakademiet.dk Friends of Gandhi : Correspondence of Mahatma Gandhi with Esther Færing (Menon), Anne Marie Petersen and Ellen Hørup / Editors: E.S.Reddy and Holger Terp. Publishers: Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum, Berlin, and the Danish Peace Academy, Copenhagen. 1st edition, 1st printing, copyright 2006 Printed in India. - ISBN 87-91085-02-0 - ISSN 1600-9649 Fred I Danmark. Det Danske Fredsakademis Skriftserie Nr. 3 EAN number / strejkode 9788791085024 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ESTHER FAERING (MENON)1 Biographical note Correspondence with Gandhi2 Gandhi to Miss Faering, January 11, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, January 15, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, March 20, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, March 31,1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, April 15, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, -

Gandhi Wields the Weapon of Moral Power (Three Case Stories)

Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power (Three Case Stories) By Gene Sharp Foreword by: Dr. Albert Einstein First Published: September 1960 Printed & Published by: Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) Phone: 079 – 27540635 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power FOREWORD By Dr. Albert Einstein This book reports facts and nothing but facts — facts which have all been published before. And yet it is a truly- important work destined to have a great educational effect. It is a history of India's peaceful- struggle for liberation under Gandhi's guidance. All that happened there came about in our time — under our very eyes. What makes the book into a most effective work of art is simply the choice and arrangement of the facts reported. It is the skill pf the born historian, in whose hands the various threads are held together and woven into a pattern from which a complete picture emerges. How is it that a young man is able to create such a mature work? The author gives us the explanation in an introduction: He considers it his bounden duty to serve a cause with all his ower and without flinching from any sacrifice, a cause v aich was clearly embodied in Gandhi's unique personality: to overcome, by means of the awakening of moral forces, the danger of self-destruction by which humanity is threatened through breath-taking technical developments. The threatening downfall is characterized by such terms as "depersonalization" regimentation “total war"; salvation by the words “personal responsibility together with non-violence and service to mankind in the spirit of Gandhi I believe the author to be perfectly right in his claim that each individual must come to a clear decision for himself in this important matter: There is no “middle ground ". -

Inspired by Gandhi: Mahatma Gandhi's Influence on Significant

112 anna katalin aklan Inspired by Gandhi: Mahatma Gandhi’s Influence on Significant Leaders of Nonviolence 113 115 #2 / 2020 history in flux pp. 115 - 124 anna katalin aklan eötvös loránd university, department of indian studies, budapest UDC <070.11:316.485Gandhi, M.>:327 https://doi.org/10.32728/flux.2020.2.6 Review article Inspired by Gandhi: Mahatma Gandhi’s Influence on Significant Leaders of Nonviolence The leader of the Indian independence movement, Mahatma Gandhi, left an invaluable legacy: he proved to the world that it was possible to achieve political aims without the use of violence. He was the first political activist to develop strategies of nonviolent mass resistance based on a solid philosophical and uniquely religious foundation. Since Gandhi’s death in 1948, in many parts of the 115 world, this legacy has been received and continued by others facing oppression, inequality, or a lack of human rights. This article is a tribute to five of the most faithful followers of Gandhi who have acknowledged his inspiration for their political activities and in choosing nonviolence as a political method and way of life: Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Martin Luther King, Louis Massignon, the Dalai Lama, and Malala Yousafzai. This article describes their formative leadership and their significance and impact on regional and global politics and history. KEYWORDS: Gandhi, nonviolence, Ghaffar Khan, Martin Luther King, Massignon, Dalai Lama, Malala Yousafzai, Gandhi’s legacy, human rights, passive resistance anna katalin aklan: Inspired by Gandhi: Mahatma Gandhi’s Influence on Significant Leaders of Nonviolence One of the most revolutionary and influential figures of twentieth- century history is undoubtedly Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the Father of the Indian Nation. -

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Gandhi's philosophy is the religious and social ideas adopted and developed by Gandhi, first during his period in South Africa from 1893 to 1914, and later of course of India. These ideas have been further developed by later "Gandhians", most notably, in India. Vinova Bhave and Jayaprakash Narayan. Outside of India some of the work of, for example, Martin Luther King Jr. can also be viewed in this light. The twin cardinal principles of Gandhi's thought are truth and non-violence. It should be remembered that the English word "truth" is an imperfect translation of the Sanskrit, "Satya", and "non violence", an even more imperfect translation of "ahimsa". Derived from "sat" - "that which exists" - "satya" contains a dimension of meaning not usually associated by English speakers with the word "truth". There are other variations too, which we need not go into here. For Gandhi, truth is the relative truth of truthfulness in word and deed, and the absolute truth- the Ultimate Reality. This ultimate truth is God (as God is also Truth) and morality- the moral laws and code - its basis. Ahimsa, far from meaning mere peacefulness or the absence of overt violence, is understood by Gandhi to denote active love - the pole opposite of violence, or "himsa", in every sense. The ultimate station Gandhi assigns non-violence stems from two main points. First, if according to the Divine Reality all life is one, then all violence committed towards another is violence towards oneself, towards the collective, whole self, and thus "self' destructive and counter to the universal law of life, which is love. -

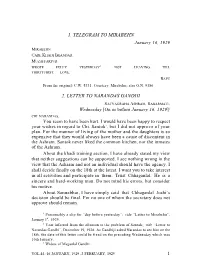

1. Telegram to Mirabehn 2. Letter to Narandas Gandhi

1. TELEGRAM TO MIRABEHN January 16, 1929 MIRABEHN CARE KHADI BHANDAR MUZAFFARPUR WROTE FULLY YESTERDAY1. NOT LEAVING TILL THIRTYFIRST. LOVE. BAPU From the original: C.W. 5331. Courtesy: Mirabehn; also G.N. 9386 2. LETTER TO NARANDAS GANDHI SATYAGRAHA ASHRAM, SABARMATI, Wednesday [On or before January 16, 1929]2 CHI. NARANDAS, You seem to have been hurt. I would have been happy to respect your wishes in regard to Chi. Santok3, but I did not approve of your plan. For the manner of living of the mother and the daughters is so expensive that they would always have been a cause of discontent in the Ashram. Santok never liked the common kitchen, nor the inmates of the Ashram. About the khadi training section, I have already stated my view that neither suggestions can be supported. I see nothing wrong in the view that the Ashram and not an individual should have the agency. I shall decide finally on the 18th at the latest. I want you to take interest in all activities and participate in them. Trust Chhaganlal. He is a sincere and hard-working man. Do not mind his errors, but consider his motive. About Sannabhai, I have simply said that Chhaganlal Joshi’s decision should be final. For no one of whom the secretary does not approve should remain. 1 Presumably a slip for “day before yesterday”; vide “Letter to Mirabehn”, January 14, 1929. 2 Year inferred from the allusion to the problem of Santok; vide “Letter to Narandas Gandhi”, December 19, 1928. As Gandhiji asked Narandas to see him on the 18th, the date of this letter could be fixed on the preceding Wednesday which was 16th January. -

100 Tributes

100 Tributes to Gandhiji on his 100 Portraits by his 100 contemporaries in their own handwritings Ramesh Thaakar Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad _ 4,500 248 Pages Hard case binding 9.5 inch x 13.25 inch Four color offset printing Enclosed in protective sleeve PUBLISHER’S NOTE The title of this volume 100 Tributes can be interpreted in two ways: these are 100 tributes to the father of the nation by Rameshbhai in form of 100 portraits… It can also be perceived as one tribute each by 100 of Gandhiji’s contemporaries… When Urvish Kothari introduced Rameshbhai Thaakar to us, we immediately knew that this was a treasure waiting to be unveiled to the world. The first thought that occurred to us was that this volume must be produced in a manner befitting its great contents and hence the idea of creating classic book with no expenses spared—perhaps deviating from the path Navajivan has taken for years—was born. This volume contains 100 portraits of Mahatma Gandhi sketched by Rameshbhai along with handwritten tribute by Gandhiji’s associate/contemporary on it. Care has been taken to reproduce the original sketches as faithfully as the technology permits. These portraits are arranged in the chronological order of the date on which the tribute was given. The Original sketches are printed on the recto—right-hand page of the book, while the facing left page contains the details like verbatim script of the original write-up along with its translation in other two languages. The page also gives the details like the name of the tribute giver in English, Hindi and Gujarati language; short introduction of that personality; the date on which the tribute was given and the original language in which the tribute is written. -

MAHATMA GANDHI – an INDIAN MODEL of SERVANT LEADERSHIP Annette Barnabas M.A.M

MAHATMA GANDHI – AN INDIAN MODEL OF SERVANT LEADERSHIP Annette Barnabas M.A.M. College of Engineering, Tiruchirappalli, India Paul Sundararajan Clifford M.A.M. B. School, Triruchirappalli, India This study explores the leadership qualities of Mahatma Gandhi in relation to six behavioral dimensions of the Servant Leadership Behaviour Scale (SLBS) model of servant leadership, proposed by Sendjaya, Sarros and Santora (2008), and highlights the importance of servant leadership qualities like service, self- sacrificial love, spirituality, integrity, simplicity, emphasizing follower needs, and modelling. It is a literary investigation of the life and leadership qualities of Gandhi, based on various books, personal correspondence, and statements including the autobiography of Mahatma Gandhi—The Story of My Experiments with the Truth—by using the model of SLBS. This research study demonstrates that Mahatma Gandhi personified the Servant Leadership Behaviour Scale model and illustrates the Indian contribution to servant leadership. It elucidates the need to include the concept of servant leadership in the curriculum of business schools and advocates the practice of servant leadership in different leadership positions. eadership is an important area of study and research in business schools for decades now. There have been numerous research findings too in the Western countries on leadership L (Jain & Mukherji, 2009, p. 435). But there is a scarcity of research on indigenous models of leadership in India, even though there are many excellent business schools in India along with skilled human talent (Jain & Mukherji, 2009, p. 435). Shahin and Wright (2004) argue that it is necessary to exercise caution when attempting to apply Western leadership theories in non- Western countries, because all concepts may not be relevant for effective leadership in these countries. -

1. Letter to Lilavati Asar 2. Letter to Prabhavati1

1. LETTER TO LILAVATI ASAR POONA, August 30, 1945 CHI. LILI, I do not remember having answered your letter. Just now, after the prayer, I have taken out the old letters. This is just to tell you that I think of you. Continue your studies and pass. Do not lose courage. Do not spoil your health. There is no time to write more. Sardar’s treatment is going on. I am well. Blessings from BAPU From a photostat of the Gujarati: C.W. 10206. Courtesy: Lilavati Asar 2. LETTER TO PRABHAVATI1 POONA, August 30, 1945 CHI. PRABHA, I do not at all remember whether I have written to you. Your letter of the 1st is lying in front of me. I am writing this after the morning prayer. I hope you keep good health. You may come when you can. Just now I shall have to stay with Sardar in Poona. I may have to be here for three months. After that I shall be touring. You should stay in the Ashram. If there is suitable work for you there and you enjoy peace of mind and keep good health, settle down there. Do as you please. How is Father? Blessings from BAPU From a photostat of the Gujarati: G.N. 3579 1 The letters are in the Devanagari script.S VOL. 88 : 30 AUGUST, 1945 - 6 DECEMBER, 1945 1 3. LETTER TO PRABHAVATI1 August 30, 1945 CHI. PRABHA, A letter from Priyamvada is enclosed. I think you should join it2 Get yourself enrolled. About the work, we shall see after you have rested in the Ashram. -

Keynote Address on Relevance of Mahatma Gandhi in Contemporary Society

International Journal of Academic Research ISSN: 2348-7666; Vol.3, Issue-10 (2), October, 2016 Impact Factor: 4.535; Email: [email protected] Keynote Address on Relevance of Mahatma Gandhi in Contemporary Society Dr. Anil Dutta Mishra Ex-Deputy Director, National Gandhi Museum, New Delhi. Mahatma Gandhi popularly known as sixty-three years of his death Gandhi Bapu or Father of the Nation is tallest continues to attract the attention of among the leaders of the world of the 20th scholars, social activists, media, policy century ever produced. He is remembered makers and dreamers not only in India all over the world for his love of peace, but throughout globe. non-violence, truth, honesty, pristine purity, compassion and his success in Present world is passing through a using these instruments to bring together critical phase of human history and is in the entire population and helping the search of an alternative. Liberalisation, country to attain independence from the privatisation and globalisation are not colonial power and show the new way to only reshaping the economy of the people the world. Gandhi was a creative man and nation but fundamentally reshaping and responding to the challenges of his culture, ideology, attitude and life style of time and setting example for present and the people across the world. Everywhere future generations. Albert Einstein, the one can see the fundamental change. great scientist rightly said that Small is being replaced by mega. Invisible “Generations to come will scare believe became visible. There is a mad race for that such a one as this ever in flesh and materialistic development resulting in blood walked upon this earth” Gandhi alienation of people from society and changed the course of history and created nature and resorting to violence of history. -

1. WHAT SHOULD BE DONE WHERE LIQUOR IS BEING SERVED? a Gentleman Asks in Sorrow:1 I Am Not Aware of Liquor Having Been Served at the Garden Party

1. WHAT SHOULD BE DONE WHERE LIQUOR IS BEING SERVED? A gentleman asks in sorrow:1 I am not aware of liquor having been served at the garden party. However, I would have attended it even if I had known it. A banquet was held on the same day. I attended it even though liquor was served there. I was not going to eat anything at either of these two functions. At the dinner a lady was sitting on one side and a gentleman on the other side of me. After the lady had helped herself with the bottle it would come to me. It would have to pass me in order to reach the gentleman. It was my duty to pass it on to the latter. I deliberately performed my duty. I could have easily refused to pass it saying that I would not touch a bottle of liquor. This, however, I considered to be improper. Two questions arise now. Is it proper for persons like me to go where drinks are served ? If the answer is in the affirmative, is it proper to pass a bottle of liquor from one person to another? So far as I am concerned the answer to both the questions is in the affirmative. It could be otherwise in the case of others. In such matters, I know of no royal road and, if there were any, it would be that one should altogether shun such parties and dinners. If we impose any restrictions with regard to liquor, why not impose them with regard to meat, etc.? If we do so with the latter, why not with regard to other items which we regard as unfeatable? Hence if we look upon attending such parties as harmful in certain circumstances, the best way seems to give up going to all such parties. -

Constructive Programme: Its Meaning and Place

Constructive Programme: Its Meaning and Place * by M. K. Gandhi “Constructive Programme” was originally addressed to the members of the Indian National Congress. It was published in 1941 and revised and enlarged in 1945. The 1945 text is re-issued here. © The Navajivan Trust Foreword This is a thoroughly revised edition of the Constructive Programme which I first wrote in 1941. The items included in it have not been arranged in any order, certainly not in the order of their importance. When the reader discovers that a particular subject though important in itself in terms of Independence does not find place in the programme, he should know that the omission is not intentional. He should unhesitant- ingly add to my list and let me know. My list does not pretend to be exhaustive; it is merely illustrative. The reader will see several new and important additions. Readers, whether workers and volunteers or not, should definitely realize that the constructive programme is the truthful and non-violent way of winning Poorna Swaraj. Its wholesale fulfilment is complete Independence. Imagine all the forty crores of people busying themselves with the whole of the constructive programme which is designed to build up the nation from the very bottom upward. Can anybody dispute the proposition that it must mean complete Independence in every sense of the expression, including the ousting of foreign domination? When the critics laugh at the proposition, what they mean is that forty crores of people will never co-operate in the effort to fulfil the programme. No doubt, there is considerable truth in the scoff. -

MAHATMA GANDHI on Terrorism And

MAHATMA GANDHI On Terrorism And War Peter Rühe Jacket - front - inside: Introduction by Michael N. Nagler www.gandhimedia.org Jacket – front – inside: Mahatma Gandhi - the Father of the Indian Nation, and the Apostle of Nonviolence. He worked for India's independence from the British rule. And gave us the awesome power of nonviolence. A social reformer, he taught the world the eternal values of love and truth. His fight for human rights, protection of environment and religious tolerance was mankind's finest hour. This book introduces the reader to the thoughts and writings of Mahatma Gandhi on nonviolence, terrorism and war. It also presents a report about Gandhi’s two visits to the nonviolent army of Abdul Ghaffar Khan at the Afghanistan border. This army, called the Red Shirts, experimented with nonviolence to pacify this violence-stricken area in the 1940’s. The texts are supported by rare images of Gandhi from the archives of his family and associates. Jacket - back - inside: Peter Rühe specialized in the collection and conservation of visual material related to Gandhi. He presented multimedia events on Gandhi in many countries and has contributed to several TV productions. Rühe is the founder of the GandhiServe Foundation, Berlin and webmaster of the largest resource on Gandhi on the internet, GandhiServe’s Mahatma Gandhi Research and Media Service – www.gandhiserve.org Peter Rühe is the author of the book Gandhi – A Photo Biography, Phaidon Press, 2001. www.gandhimedia.org The writings by Mahatma Gandhi are published by permission of the Navajivan Trust, Ahmedabad - 380 014 (India). www.gandhimedia.org Dedicated to the Conscience of Humanity www.gandhimedia.org C o n t e n t s Contents Preface Introduction by Michael N.