C. Supporting Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alpine Ibex, Capra Ibex

(CAPRA IBEX) ALPINE IBEX by: Braden Stremcha EVOLUTION Alpine ibex is part of the Bovidae family under the order Artiodactyla. The Capra genus signifies this species specifically as a wild goat, but this genus shares very similar evolutionary features as species we recognize in Montana like Oreamnos (mountain goat) and Ovis (sheep). Capra, Oreamnos, and Ovis most likely derived in evolution from each other due to glacial migration and failure to hybridize between genera and species.Capra ibex was first historically observed throughout the central Alpine Range of Europe, then was decreased to Grand Paradiso National Park in Italy and the Maurienne Valley in France but has since been reintroduced in multiple other countries across the Alps. FORM AND FUNCTION Capra ibex shares a typical hoofed unguligrade foot posture, a cannon bone with raised calcaneus, and the common cursorial locomotion associated with species in Artiodactyla. These features allow the alpine ibex to maneuver through the steep terrain in which they reside. Specifically, for alpine ungulates and the alpine ibex, more energy is put into balance and strength to stay on uneven terrain than moving long distances. Alpine ibexes are often observed climbing artificial dams that are almost vertical to lick mineral deposits! This example shows how efficient Capra ibex is at navigating steep and dangerous terrain. The most visual distinction that sets the Capra genus apart from others is the large, elongated semicircular horns. Alpine ibex specifically has horns that grow throughout their life span at an average of 80mm per year in males. When winter comes around this growth is stunted until spring and creates an obvious ring on the horn that signifies that year’s overall growth. -

The Camel Farm Maintain an Enclosure Housing Goats in 15672 South Ave

received a repeat citation for failing to The Camel Farm maintain an enclosure housing goats in 15672 South Ave. 1 E., Yuma, Arizona good repair. It had fencing with metal edges that were bent inward, sharp points protruding into the enclosure, and a gap The Camel Farm, operated by Terrill Al- large enough for an animal’s leg or head to Saihati, has failed to meet minimum become stuck. The facility was also cited for standards for the care of animals used in failing to maintain the perimeter fence in exhibition as established in the federal good repair and at a sufficient height of 8 Animal Welfare Act (AWA). The U.S. feet to function as a secondary containment Department of Agriculture (USDA) has system for the animals in the facility. A repeatedly cited The Camel Farm for section of the perimeter fence had a numerous infractions, including failing measured height of 5 feet, 4 inches. to provide animals (including sick, wounded, and lame ones) with adequate October 9, 2019: The USDA issued The veterinary care, failing to maintain Camel Farm a repeat citation for failing to enclosures in good repair, failing to have a method to remove pools of standing provide animals with drinking water, water around the water receptacles in failing to have an adequate number of enclosures housing a zebra, a donkey, employees to supervise contact between camels, and goats. The animals were the public and animals, failing to unable to drink from the receptacles without maintain clean and sanitary water standing in the water and mud. -

Favourableness and Connectivity of a Western Iberian Landscape for the Reintroduction of the Iconic Iberian Ibex Capra Pyrenaica

Favourableness and connectivity of a Western Iberian landscape for the reintroduction of the iconic Iberian ibex Capra pyrenaica R ITA T. TORRES,JOÃO C ARVALHO,EMMANUEL S ERRANO,WOUTER H ELMER P ELAYO A CEVEDO and C ARLOS F ONSECA Abstract Traditional land use practices declined through- Keywords Capra pyrenaica, environmental favourableness, out many of Europe’s rural landscapes during the th cen- graph theory, habitat connectivity, Iberian ibex, reintroduc- tury. Rewilding (i.e. restoring ecosystem functioning with tion, ungulate minimal human intervention) is being pursued in many areas, and restocking or reintroduction of key species is often part of the rewilding strategy. Such programmes re- Introduction quire ecological information about the target areas but this is not always available. Using the example of the an has shaped landscapes for centuries (Vos & Iberian ibex Capra pyrenaica within the Rewilding Europe Meekes, ). In the last decades socio-economic M framework we address the following questions: ( ) Are and lifestyle changes have driven a rural exodus and the there areas in Western Iberia that are environmentally fa- abandonment of land throughout many of Europe’s rural vourable for reintroduction of the species? ( ) If so, are landscapes (MacDonald et al., ; Höchtl et al., ). these areas well connected with each other? ( ) Which of In some cases sociocultural and economic problems have these areas favour the establishment and expansion of a vi- created new opportunities for conservation (Theil et al., ). able population -

A Comparative Study on the Physicochemical Parameters Of

ienc Sc es al J ic o u Legesse et al., Chem Sci J 2017, 8:4 m r e n a h l DOI: 10.4172/2150-3494.1000171 C Chemical Sciences Journal ISSN: 2150-3494 Research Article Open Access A Comparative Study on the Physicochemical Parameters of Milk of Camel, Cow and Goat in Somali Regional State, Ethiopia Legesse A1*, Adamu F2, Alamirew K2 and Feyera T3 1Department of Chemistry, College of Natural and Computational Science, Ambo University, Ethiopia 2College of Natural and Computational Science, Jigjiga University, Ethiopia 3Department of Biomedical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Ethiopia *Corresponding author: Abi Legesse, Department of Chemistry, College of Natural and Computational Science, Ambo University, Ethiopia, Tel: +251 11 236 2006; E- mail: [email protected] Received date: September 25, 2017; Accepted date: October 03, 2017; Published date: October 06, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Legesse A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract This research was carried out to investigate key physicochemical parameters of milk samples collected from camel, cow and goat in Jigjiga district, Eastern Ethiopia. Sixty fresh milk samples were collected purposively from camels, cows and goats (twenty samples from each species) and analyzed. The results revealed that, cow milk had 6.30 ± 0.15 pH, 0.29 ± 0.04% titratable acidity, 14.6 ± 0.60% total solid, 0.75 ± 0.07% ash, 3.54 ± 0.12% protein, 5.54 ± 0.65% fat and 1.06 ± 0.03 specific gravity. -

Comparative Food Habits of Deer and Three Classes of Livestock Author(S): Craig A

Comparative Food Habits of Deer and Three Classes of Livestock Author(s): Craig A. McMahan Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Oct., 1964), pp. 798-808 Published by: Allen Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3798797 . Accessed: 13/07/2012 12:15 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Allen Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Wildlife Management. http://www.jstor.org COMPARATIVEFOOD HABITSOF DEERAND THREECLASSES OF LIVESTOCK CRAIGA. McMAHAN,Texas Parksand Wildlife Department,Hunt Abstract: To observe forage competition between deer and livestock, the forage selections of a tame deer (Odocoileus virginianus), a goat, a sheep, and a cow were observed under four range conditions, using both stocked and unstocked experimental pastures, on the Kerr Wildlife Management Area in the Edwards Plateau region of Texas in 1959. The animals were trained in 2 months of preliminary testing. The technique employed consisted of recording the number of bites taken of each plant species by each animal during a 45-minute grazing period in each pasture each week for 1 year. -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

Central Eurasian Aridland Mammals Action Plan

CMS CONVENTION ON Distr. General MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/ScC17/Doc.13 SPECIES 8 November 2011 Original: English 17 th MEETING OF THE SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL Bergen, 17-18 November 2011 Agenda Item 17.3.6 CENTRAL EURASIAN ARIDLAND MAMMALS ACTION PLAN (Prepared by the Secretariat) Following COP Recommendation 9.1 the Secretariat has prepared a draft Action Plan to complement the Concerted and Cooperative Action for Central Eurasian Aridland Mammals. The document is a first draft, intended to stimulate discussion and identify further action needed to finalize the document in consultation with the Range States and other stakeholders, and to agree on next steps towards its implementation. Action requested: The 17 th Meeting of the Scientific Council is invited to: a. Take note of the document and provide guidance on its further development and implementation; b. Review and advise in particular on the definition of the geographic scope, including the range states, and the target species (listed in table 1); and c. Provide guidance on the terminology currently used for the Action Plan, agree on a definition of the term aridlands and/or consider using the term drylands instead. Central Eurasian Aridland Mammals Draft Action Plan Produced by the UNEP/CMS Secretariat November 2011 1 Content 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Vision and Main Priority Directions ................................................................................................... -

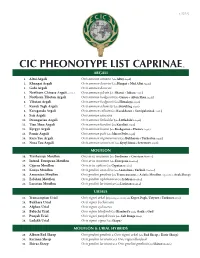

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

RCN #33 21/8/03 13:57 Page 1

RCN #33 21/8/03 13:57 Page 1 No. 33 Summer 2003 Special issue: The Transformation of Protected Areas in Russia A Ten-Year Review PROMOTING BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION IN RUSSIA AND THROUGHOUT NORTHERN EURASIA RCN #33 21/8/03 13:57 Page 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS Voice from the Wild (Letter from the Editors)......................................1 Ten Years of Teaching and Learning in Bolshaya Kokshaga Zapovednik ...............................................................24 BY WAY OF AN INTRODUCTION The Formation of Regional Associations A Brief History of Modern Russian Nature Reserves..........................2 of Protected Areas........................................................................................................27 A Glossary of Russian Protected Areas...........................................................3 The Growth of Regional Nature Protection: A Case Study from the Orlovskaya Oblast ..............................................29 THE PAST TEN YEARS: Making Friends beyond Boundaries.............................................................30 TRENDS AND CASE STUDIES A Spotlight on Kerzhensky Zapovednik...................................................32 Geographic Development ........................................................................................5 Ecotourism in Protected Areas: Problems and Possibilities......34 Legal Developments in Nature Protection.................................................7 A LOOK TO THE FUTURE Financing Zapovedniks ...........................................................................................10 -

Ungulate Tag Marketing Update Aza Midyear Conference 2015 Columbia, Sc

UNGULATE TAG MARKETING UPDATE AZA MIDYEAR CONFERENCE 2015 COLUMBIA, SC Brent Huffman - Toronto Zoo Michelle Hatwood - Audubon Species Survival Center RoxAnna Breitigan - Cheyenne Mountain Zoo Species Marketing Original Goals Began in 2011 Goal: Focus institutional interest Need to stop declining trend in captive populations Target: Animal decision makers Easy accessibility 2015 Picked 12 priority species to specifically market for sustainability Postcards mailed to 212 people at 156 institutions Postcards Printed on recycled paper Program Leaders asked to provide feedback Interest Out of the 12 Species… . 8 Program Leaders were contacted by new interested parties in 2014 Sitatunga- posters at AZA meeting Bontebok- Word of mouth, facility contacted TAG Urial- Received Ungulate postcard Steenbok- Program Leader initiated contact Bactrian Wapiti- Received Ungulate postcard Babirusa- Program Leader initiated contact Warty Pigs- WPPH TAG website Arabian Oryx- Word of mouth Results Out of the 12 Species… . 4 Species each gained new facilities Bontebok - 1 Steenbok - 1 Warty Pig - 2 (but lost 1) Babirusa - 4 Moving Forward Out of the 12 Species… . Most SSP’s still have animals available . Most SSP’s are still looking for new institutions . Babirusa- no animals available . Anoa- needs help to work with private sector to get more animals . 170 spaces needed to bring these programs up to population goals Moving Forward Ideas for new promotion? . Continue postcards? Posters? Promotional items? Advertisements? Facebook? Budget? To be announced -

Scaling-Up Multi-Hazard Early Warning System and the Use of Climate Information in Georgia

Annex VI (b) – Environmental and Social Assessment Report Green Climate Fund Funding Proposal I Scaling-up Multi-Hazard Early Warning System and the Use of Climate Information in Georgia Environmental and Social Assessment Report FP-UNDP-5846-Annex-VIb-ENG 1 Annex VI (b) – Environmental and Social Assessment Report Green Climate Fund Funding Proposal I CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 8 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 10 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................. 10 1.2 Description of the Project ............................................................................................................ 10 1.2.1 Summary of Activities .......................................................................................................... 11 1.3 Project Alternatives ..................................................................................................................... 27 1.3.1 Do Nothing Alternative ........................................................................................................ 27 1.3.2 Alternative Locations .......................................................................................................... -

22.NE/23 Weinberg 375-394*.Indd

Galemys 22 (nº especial): 375-394, 2010 ISSN: 1137-8700 CLINEAL VARIATION IN CAUCASIAN TUR AND ITS TAXONOMIC RELEVANCE PAVEL J. WEINBERG1, MUZHIGIT I. AKKIEV2 & RADION G. BUCHUKURI 1. North Ossetian Nature reserve, Basieva str. 1, Alagir, RSO-Alania, Russia 363245. ([email protected]) 2. Kabardin-Balkarian Highland Nature Reserve, Kashkhatau, No. 78, KBR, Russia 631800. ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Geographic variation in traits and features used in traditional morphology have been studied in Caucasian tur (e.g. degree of spiraling of horn sheaths and cores in males and females, shape of cross-section of adult males horn cores, dark stripe pattern on the legs etc.). Almost all the examined traits display clineal east-west variation, usually with sloping parts of the cline to the west and east (longer one) from the area around Mt. Elbrus, while in this area a steep part of the cline occurs, often with considerable fluctuations within. Resembling clineal variation occurs in tur females as well. Multiple correlating clineal variation in large and actively moving ungulate within a limited range (770 km long and up to 80 km wide) can hardly be explained by geographic dynamics of environmental factors. The shape of the cline is also very telling, suggesting a secondary contact and hybridization (Mayr 1968). Since there is one steep part of the cline, contact of two primary taxa may have occurred, initially separated by a geographic barrier, most probably a glaciation centre which was pulsating during Pleistocene in the area including Mnts. Elbrus in the west and Kazbek in the east, situated where the steep and fluctuating part of the cline occurs.