Claypotts Castle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh Mackay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2012 "For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland Andrew Phillip Frantz College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Frantz, Andrew Phillip, ""For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 480. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/480 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SO GOOD A CAUSE”: HUGH MACKAY, THE HIGHLAND WAR AND THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION IN SCOTLAND A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors is History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Andrew Phillip Frantz Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________ Nicholas Popper, Director _________________________________________ Paul Mapp _________________________________________ Simon Stow Williamsburg, Virginia April 30, 2012 Contents Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter I The Origins of the Conflict 13 Chapter II Hugh MacKay and the Glorious Revolution 33 Conclusion 101 Bibliography 105 iii Figures 1. General Hugh MacKay, from The Life of Lieutenant-General Hugh MacKay (1836) 41 2. The Kingdom of Scotland 65 iv Acknowledgements William of Orange would not have been able to succeed in his efforts to claim the British crowns if it were not for thousands of people across all three kingdoms, and beyond, who rallied to his cause. -

Macg 1975Pilgrim Web.Pdf

-P L L eN cc J {!6 ''1 { N1 ( . ~ 11,t; . MACGRl!OOR BICENTDmIAL PILGRIMAGE TO SCOTLAND October 4-18, 197.5 sponsored by '!'he American Clan Gregor Society, Inc. HIS'lORICAL HIGHLIGHTS ABO ITINERARY by Dr. Charles G. Kurz and Claire MacGregor sessford Kurz , Art work by Sue S. Macgregor under direction of R. James Macgregor, Chairman MacGregor Bicentennial Pilgrimage booklets courtesy of W. William Struck, President Ambassador Travel Service Bethesda, Md • . _:.I ., (JUI lm{; OJ. >-. 8IaIYAt~~ ~~~~ " ~~f. ~ - ~ ~~.......... .,.; .... -~ - 5 ~Mll~~~. -....... r :I'~ ~--f--- ' ~ f 1 F £' A:t::~"r:: ~ 1I~ ~ IftlC.OW )yo X, 1.. 0 GLASGOw' FOREWORD '!hese notes were prepared with primary emphasis on MaoGregor and Magruder names and sites and their role in Soottish history. Secondary emphasis is on giving a broad soope of Soottish history from the Celtio past, inoluding some of the prominent names and plaoes that are "musts" in touring Sootland. '!he sequenoe follows the Pilgrimage itinerary developed by R. James Maogregor and SUe S. Maogregor. Tour schedule time will lim t , the number of visiting stops. Notes on many by-passed plaoes are information for enroute reading ani stimulation, of disoussion with your A.C.G.S. tour bus eaptain. ' As it is not possible to oompletely cover the span of Scottish history and romance, it is expected that MacGregor Pilgrims will supplement this material with souvenir books. However. these notes attempt to correct errors about the MaoGregors that many tour books include as romantic gloss. October 1975 C.G.K. HIGlU.IGHTS MACGREGOR BICmTENNIAL PILGRIMAGE TO SCOTLAND OCTOBER 4-18, 1975 Sunday, October 5, 1975 Prestwick Airport Gateway to the Scottish Lowlands, to Ayrshire and the country of Robert Burns. -

From Battle to Ballad: "Gallant Grahams" of the 17Th Century

Extracted from: Lloyd D. Graham (2020) House GRAHAM: From the Antonine Wall to the Temple of Hymen, Lulu, USA. From battle to ballad: “Gallant Grahams” of the 17th century Historical context The setting for this chapter is the complex and often confusing clash between the Covenanters – the Scottish Presbyterians who opposed the Episcopalian (Anglican) reforms imposed on their Kirk by Charles I in 1637 – and the Royalists, who supported the king. To begin with, the Covenanters raised an army and defeated Charles in the so- called Bishops’ Wars. The ensuing crisis in the royal House of Stuart (Stewart) helped to precipitate the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which included the English Civil War, the Scottish Civil War and Irish Confederate Wars. For the following decade of civil war in Britain, the Covenanters were the de facto government of Scotland. In 1643, military aid from Covenanter forces helped the Parliamentarian side in the English Civil War (“Roundheads”) to achieve victory over the king’s Royalist faction (“Cavaliers”). In turn, this triggered civil war in Scotland as Scottish Royalists – mainly Catholics and Episcopalians – took up arms against the Covenanters to oppose the impending Presbyterian domination of the Scottish religious landscape by an increasingly despotic Kirk. It is in the turmoil of this setting that Sir James Graham of Montrose (Fig. 7.1), the first of the two leaders discussed in the present chapter, plays a key role. Initially a Covenanter himself – he had signed the National Covenant in 1638 – he had effectively switched sides by 1643, becoming a leader of the Scottish Royalists. -

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Killiecrankie Designation

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Killiecrankie The Inventory of Historic Battlefields is a list of nationally important battlefields in Scotland. A battlefield is of national importance if it makes a contribution to the understanding of the archaeology and history of the nation as a whole, or has the potential to do so, or holds a particularly significant place in the national consciousness. For a battlefield to be included in the Inventory, it must be considered to be of national importance either for its association with key historical events or figures; or for the physical remains and/or archaeological potential it contains; or for its landscape context. In addition, it must be possible to define the site on a modern map with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The aim of the Inventory is to raise awareness of the significance of these nationally important battlefield sites and to assist in their protection and management for the future. Inventory battlefields are a material consideration in the planning process. The Inventory is also a major resource for enhancing the understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of historic battlefields, for promoting education and stimulating further research, and for developing their potential as attractions for visitors. Designation Record and Full Report Contents Name - Context Alternative Name(s) Battlefield Landscape Date of Battle - Location Local Authority - Terrain NGR Centred - Condition Date of Addition to Inventory Archaeological and Physical Date of Last Update Remains and -

English, the Exploits of the Swashbuckling 'Harry Hotspur' and the Guy Fawkes Plot

Heart of Scotland Tour Highlights Alnwick Castle Alnwick Castle is one of the largest inhabited castles in Europe and home to the Dukes of Northumberland for over 700 years. During this time the castle has played a role in many historical events from the Wars of Independence between the Scots and English, the exploits of the swashbuckling 'Harry Hotspur' and the Guy Fawkes plot. The castle is beautifully preserved, one of the reasons why it's such a Hollywood favourite and been used as a location for numerous films including 'Robin Hood Prince of Thieves' and all seven 'Harry Potter' movies. The adjoining Alnwick Garden is one of the world's most ambitious new gardens. The Duchess of Northumberland's charitable vision focuses around the Grand Cascade and various water sculptures but also includes the Poison Garden and one of the world's largest tree houses. Blair Castle Blair Castle is the ancient seat of the Dukes and Earls of Atholl and holds an important place in Scotland's history. Strategically located in the Strath of Garry, whoever held Blair Castle was gatekeeper to the Grampian Mountains - the most direct route north to Inverness. It was twice besieged, first by Oliver Cromwell's army in 1652 and then by the Jacobites in 1746, just before their final defeat at the battle of Culloden. The grounds and gardens are home to some of Britain's tallest trees, a nine-acre walled garden and St Bride's Kirk, the final resting place of the Jacobite hero 'Bonnie Dundee'. Dating back to 1269, the castle opened its doors to the public in 1936, one of the first great houses in Britain to do so. -

Jacobite Cd.Pdf

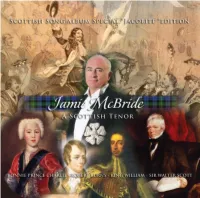

Jamie Mcbrid e - A Sco t tish Teno r In this CD I wanted to tell the story of Scotland’s history through song. Our present and our future are shaped by our past, and how we see ourselves as Scots is reflected in our songs. My choice of songs tells of the Scots pride in their nation, their battle for freedom and their passion for their country. Our history is one of tragedy and triumph, Scotland may have been defeated, but the Scots have never been conquered. Many of these songs are accompanied by the pipes, for the sound of the pipes is an emotive one for Scots, whether a rousing march or a sad lament. For those who have left Scotland, it is the sound of the pipes that will remind them of their homeland and its past. This past is reflected in the words of this Scottish Song Collection. Throughout my lifetime, I have sung with various companies including Rsnoc, Edinburgh Grand Opera, Edinburgh Southern light opera and Allegro. I have recently also recorded my “Giacomo Puccini favourite arias album” which is now available. In earlier years I sang in a rock band called ‘Tartan‘ touring the middle east while working in the oil industry. After completing my work in the middle east I entered into business and raised a family in Edinburgh. I also attended Napier University, and worked with various vocal teachers in summer school master classes along with the late Franco Corelli in Florence which is a highlight in my life that I fondly remember. -

NA H-EILTHIRICH Margaret Macleod (Vocal

1 NA H-EILTHIRICH Margaret MacLeod (vocal); Noel Eadie (mandolin, vocal); Donnie MacLeod (guitar, vocal) Recorded 102 Maxwell Street, Glasgow, ca l960 CAL-7523 Thoir mo shoraidh that ghunaidh (trad) (Argyll) Gaelfonn G-7601(7”.45) CAL-7524 Thug-o-lathaill o-horo – a seinn (Jacobite) (Macmhaighstir Alasdair) Gaelfonn G-7601(7”.45) PETER NAIRN Pseudonym on Grand Pree 18071 for Robert Burnett MARIE NARELLE (Catherine Mary Ryan) (Tamora, Australia, 1870 – London, 1941). Soprano vocal with orchestra Recorded London, early 1900s Bonnie Dundee (Walter Scott; trad) Edison 2288(cyl) Jessie, the flower o’ Dunblane (Robert Tannahill; R. A. Smith) Edison 2289(cyl) Comin’ thro’ the rye (Robert Burns; Robert Brenner) Edison 9254(cyl) Bonnie banks of Loch Lomond (trad) Edison 9325(cyl) Recorded London, ca September 1910 Auld lang syne (Robert Burns; trad) Edison 525(cyl) Bonnie Doon (Ye banks and braes) (Robert Burns; Charles Miller) Edison 687, 1974(cyl) Annie Laurie (William Douglas; Lady Alicia Scott) Edison 862, 9422(cyl) NATIONAL FOLK DANCE ORCHESTRA Dr. R. Vaughan Williams, conductor (Down Ampney, 1872 - 1958). Recorded Petty France, London, Friday, 12th. May 1930 WA-10373-2 Hunsdon House – folk dance (trad. arr. Cecil J. Sharp) Col DB-181 WA-10374-1 Geud man of Ballangigh – folk dance (trad. arr. Cecil J. Sharp) Col DB-181 Stanford Robinson, conductor (Leedrums, 1904 – Brighton, 1984) Recorded Central Hall, Storeys Gate, Westminster, London, Friday, 11th. July 1930 WA-10555-1 Regimental marches – part 9. Black Watch; Royal Highlanders; Gordon Highlanders; Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders; Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders; Princess Louise’s Col DB-238 WA-10556-2 Regimental marches. -

The Wild Glen Sae Gkeen. Rev

CHRONOLOGICALLY ARRANGED. 477 THE WILD GLEN SAE GKEEN. REV. HENRY S. RIDDELL, WAS born at Sorbio, Dumfriesshire, in 1798. His father was a Shepherd, and he followed the same occupation till he managed to scrape together sufficient money to enable him to enter the University of Edinburgh. He became a licentiate of the Church of Scotland, but never took any active part in the ministry: he resided at Teviothead, where the Duke of Buccleuch generously allowed him the use of a cottage, a small annuity, and a grant of land. Mr. Eiddell died in 1870. Mr. Eiddell published several volumes of poetry during his life-time, and had the rare pleasure of seeing several of his songs achieve an instant " " and enthusiastic popularity. The Wild Glen sae Green," The Crook " and the Plain," and above all, the inspiriting Scotland yet," have taken a secure position amongst our popular minstrelsy. His works are pre- sently being edited by Dr. Brydon, of Hawick, with a view to the issue of a complete collected edition. WHEN my flocks upon the heathy hill are lying a' at rest, And the gloamin' spreads its mantle grey o'er the world's dewy breast, I'll tak' my plaid and hasten through yon woody dell unseen, And meet my bonnie lassie on the wild glen sae green. I'll meet her by the trystin' tree that's stannin' a' alane, Where I have carved her name upon the little moss-grey stane, There I will clasp her to my breast, and bo mair blest, I ween, Than a' that are ancath the sky, in the wild glen sae green. -

The Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society OPENING OF

Lia 0 TGE The Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society Vol. 114 No. 8 £1.50 August/September 2009 CONWAY HALL'S 80-ni BIRTHDAY SOUTH PLACE ETHICAL SOCIETY CONWAY HALL, RED LION SQUARE, HOLBORN, W.C,1 THE COMMITTEE HAVE MUCH PLEASURE' IN INVITING YOU TO, THE . OPENING OF CONWAY HALL On MONDAY, 23rd SEPTEMBER,'1929, at 7 p.m. C OELISLE BURNS, M.A, D.Lit. • - - IN THE CHAIR SPEAKERS: Prof. GILBERT MURRAY Prof. GRAHAM WALLAS JOHN A. HOBSON, M.A. RICHARD H. WALTHEW ATHENE SEYLER MUSIC Pianoforfor M AURICE COLE Violin INIFRED SMALL LIGHT REIRESHMENTS R S.V.P. lu Mat RICHARDS CONWAY HALL. RED LION SO- W.C.I DOORS OPEN SOO I PLEASE SPINS THIS CARD WITH YOU . 80 years ago, the speakers at the opening of Conway Hall on 23 September 1929 (see invitation card above) enthused at the opportunities for promoting humanist ideas they believed it would offer. It was to be a centre where all the various allied organisations could meet, study, develop and expound their philosophy in a congenial atmosphere. The Ethical Society, which built, owns and manages Conway Hall has a democratic constitution. Members of SPES who wish to take a more active part in this important work are urged to put themselves forward for election to the General Committee this year. INTELLECTUALLY RESPECTABLE CREATIONISM Donald Rooum 3 ALTERNATIVE 'THOUGHT FOR TIIE DAY' — Book Review Barbara Smoker 6 VIEWPOINTS: H. Frankel, Suzette Henke, Brian Blangford, Ian Buxton 7 HOW HUMANS CAME TO INVENT RELIGION Norman Bacrac 9 WILLIAM McGONAGALL (1825-1902): THE WORLD'S GREATEST BAD POET? Iain King 10 ETHICAL SOCIETY EVENTS 16 SOUTH PLACE ETHICAL SOCIETY Conway Hall Humanist Centre 25 Red Lion Square, London WC IR 4RL. -

The Covenanters

3/20/2011 Covenanters The Covenanters The Fifty Years Struggle 1638-1688 "The Battle of Drumclog" by Sir George Harvey RSA - 1836 Introduction This chapter of history is surprisingly unknown and undocumented outside the borders of Scotland. However it was a violent period that pitted fellow countrymen against each- other, rather like the English Civil War that took place around the same time. Although on a smaller scale it was often more brutal as the following chapters will describe: Today South West Scotland is a peaceful and largely prosperous area, however there survive a large number of 'martyrs' graves, which are reminders of an altogether more turbulent past. Many are located on remote moorland, marking the spot where government soldiers killed supporters of the Covenant. Others are to be found in parish Kirkyards either erected at the time or often replaced by modern memorials. Almost every corner of southern Scotland has a tale to tell of the years of persecution, from remote and ruinous shepherds' houses where secret meetings were held to castles and country houses commandeered by government troops in their quest to capture and punish those who refused to adhere to the King's religious demands. http://www.sorbie.net/covenanters.htm 1/32 3/20/2011 Covenanters Scotland was in an almost constant state of civil unrest because people refused to accept the royal decree that King Charles was head of the church (known as the 'Kirk'). When those who refused signed a covenant which stated that only Jesus Christ could command such a position, they were effectively signing their own death warrant. -

2016 It's Your Neighbourhood Certificates

2016 It’s Your Neighbourhood Certificates In addition to the following certificates, 23 groups were awarded with Certificates of Distinction. The award is given to groups which have consistently grown and improved their performance over the years that they have participated in the It’s Your Neighbourhood campaign. Level 5 - Outstanding Battlefield Community Garden (Glasgow City) Bonnie Dundee Group (Dundee City) Burgh Beautiful: 3 Beds with a Message (West Lothian) Burnside in Bloom (South Lanarkshire) CLEAR Buckhaven (Fife) Communities Along the Carron (Falkirk) Community Green Initiative (CGI) (Falkirk) Craigneuk Allotment Association (North Lanarkshire) Dalmuir Park Restoration Project (West Dunbartonshire) East Wemyss & McDuff Community Council (Fife) Forth Eco Project (South Lanarkshire) Friends of Centenary & West End Parks Airdrie (North Lanarkshire) Friends of Duthie Park (Aberdeen City) Friends of Seaton Park (Aberdeen City) Friends of Seven Acre Park (City of Edinburgh) Friends of Starbank Park (City of Edinburgh) Friends of the Barnhill Rock Garden (Dundee City) Friends of Union Terrace Gardens (Aberdeen City) Garthdee Field Allotments Association (Aberdeen City) Gateway Residents Association (Glasgow City) Getting Better Together Ltd (North Lanarkshire) Glenboig Neighbourhood House (North Lanarkshire) Greener Cambusbarron (Stirling) Greenhead Moss Community Group (North Lanarkshire) Grow in Glenburn (Renfrewshire) Hazlehead Primary School - Community Group (Aberdeen City) Innellan Wildlife Watch Group (Argyll & Bute) Inverurie -

William Topaz Mcgonagall - Poems

Classic Poetry Series William Topaz McGonagall - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive William Topaz McGonagall(1830 - 1902) William Topaz McGonagall was born of rather poor Irish parents in Edinburgh, Scotland, in March 1825. In his nearly unreadable, rambling biographical notes1, one eventually learns that he sprang from a family of five children and that he worked with his father as a handloom weaver. His education appears to have been patchy, but, in his own words, 'William has been like the immortal Shakespeare he had learned more from nature than he ever learned at school'. The family settled in Dundee while William was still a boy, and he lived there for the rest of his life. He died in 1902. As a grown man, he continued to work in the family trade, and married one Jean King in 1846. At about this time he also began to participate in amateur theatrics, acting in Shakespearean drama at the Dundee theatre. The Muse of Poetry appears to have captured his imagination, if not his talent, in the 1870s, beginning with a paean to a new railway bridge over the Tay River at Dundee in 1877. By McGonagall's own account, the poem was '... received with eclat and [he] was pronounced by the Press the Poet Laureate of the Tay Bridge...'. And after that he never stopped. His first collection of Poetic Gems was published in 1878, and he published several more Collected Gems during his lifetime as well as many broadsheets. He also toured Scotland, England, and New York in the United States, giving public readings for which he charged admission.