The American Catholic Church As a Political Institution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allegations Against Cardinal Mccarrick Raise Difficult Questions

Allegations against Cardinal McCarrick raise difficult questions A new allegation of child sexual abuse was leveled against Cardinal Theodore McCarrick last Thursday, one month after the June announcement that he had been suspended from priestly ministry following an investigation into a different charge of sexual abuse on the part of the cardinal. Along with emerging accounts from priests and former seminarians of sexual coercion and abuse by McCarrick, those allegations paint a picture of McCarrick’s sexual malfeasance that may be among the most grave, tragic, and, for many Catholics, infuriating, as any in recent Catholic history. From all corners of the Church, questions are being raised about those who might have known about McCarrick’s misconduct, about how the Church will now handle the allegations against McCarrick, and about what it means for the Church that a prominent, powerful, and reportedly predatory cleric was permitted to continue in ministry for decades without censure or intervention. Because McCarrick was a leading voice in the Church’s 2002 response to the sexual abuse crisis in the United States, and an architect of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Dallas Charter of the same year, the credibility of that response has also, for some, come into question. For parents and others who placed trust in the Church to secure a safe environment for children, those questions are especially important. At the USCCB’s 2002 Spring Assembly in Dallas, the bishops drafted their Charter for the Protection of Young People and the Essential Norms for Diocesan/Eparchial Policies Dealing with Allegations of Sexual Abuse of Minors by Priests or Deacons, under intense media scrutiny. -

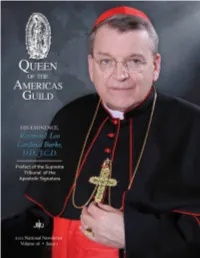

2012 Newsletter

Queen of the Americas Guild 1 From the President…. Another year has come and As much as most of us hate change, sometimes we are gone, and somehow it is time forced to adapt. This past year has been a challenging again to check in with the one personally for myself and my wife, Beverly. We devoted members of the Queen have both dealt with some health issues, especially of the Americas Guild. While Beverly, which has forced us to slow down and re- some things remain the same (a evaluate some things. We have not been able to devote difficult economy for non-profits, as much time as usual to the Guild or our business. We continued association with the also know that we can depend on Rebecca Nichols, Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe Guild National Coordinator, to take care of the day-to- in La Crosse), there are definitely day operations of the Guild. However, there is a silver some changes afoot. lining. Our son, Christopher, has agreed to join the Guild’s Board of Directors (pending board approval). Our retreat center near the Basilica in Mexico City is Christopher has been associated with the Guild in not yet a reality and the work towards it continues. an unofficial way for virtually his entire life, joining However, there has been some promising activity us on pilgrimage and going to Guild events since he on that front; more positive than we have had in was a small child. He is keenly aware of the goals of many years. -

NOCERCC Nwsltr December 2008

News Notes Membership Newsletter Winter 2009 Volume 36, No. 1 CONVENTION 2009 IN ALBUQUERQUE: A CONVERSATION The NOCERCC community gathers February 16-19, 2009 as the Archdiocese of Santa Fe welcomes our thirty-sixth annual National Convetion to Albuquerque. News Notes recently spoke with Rev. Richard Chiola, a member of the 2009 Convention Committee, about the upcoming convention. Fr. Chiola is director of ongoing formation of priests for the Diocese of Springfield in Illinois and pastor of St. Frances Cabrini Church in Springfield. He is also the Author of Catholicism for the Non-Catholic (Templegate Publishers, Springfield, IL, 2006). In This Issue: Convention 2009 in Albuquerque: A Conversation.................... 1&3 2009 President’s Distinguished Service Award....................... 2 2009 NOCERCC National Albuquerque, New Mexico Convention............................ 4 NEWS NOTES: Please describe the overall theme of the convention. Rev. Richard Chiola: The ministry of the Word is one of the three munera or ministries which the ordained engage in for the sake Tool Box................................. 5 of all the faithful. As the USCCB’s The Basic Plan for the Ongoing Formation of Priests indicates, each of these ministries requires a priest to engage in four dimensions of ongoing formation. The convention schedule will explore those four dimensions (the human, the spiritual, the intellectual, and the pastoral) for deeper appreciation of the complexity of the ministry of the Word. Future conventions will explore each of the other two ministries, sanctification and governance. 2009 Blessed Pope John XXIII Award.................................... 5 The 2009 convention will open with a report from Archbishop Donald Wuerl about the Synod held in the fall of 2008 on the ministry of the Word. -

BISHOPS CONFERENCE Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE To the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB): "What we hope for from the National Conference Assembly of Bishops in Baltimore on November 12-14, 2018." Leadership from Baltimore area Catholic churches are heartened by the three goals Cardinal Daniel DiNardo announced in his 16 August statement on the measures to be taken by the USCCB and the Holy See to address the moral catastrophe that has overtaken the Church. An open letter created by the St. Ignatius "Women of the New Testament Ministry" has now been sent to DiNardo, Archbishop William Lori, and his auxiliary bishops which proposes further steps in increased accountability and transparency we believe necessary for restoring trust in the bishops and for advancing the reform of the clerical culture of the Church. That letter can be accessed here. We would appreciate your support in this effort as the USCCB gathers in Baltimore on November 12–14 to discuss "stronger protections against predators in the Church and anyone who would conceal them, protections that will hold bishops to the highest standards of transparency and accountability." If you agree with what is proposed in the open letter, would you please share it with friends at parishes and ask them to support this effort? This can be accomplished by doing the following: 1. Print out letter (upload letter) 2. Sign it 3. Mail it to Cardinal DiNardo at the address listed in letter. For the maximum impression, the letters should be received by Cardinal DiNardo before the Conference begins. The Conference will be held at the Baltimore Marriott Waterfront. -

Newsletter 2020 I

NEWSLETTER EMBASSY OF MALAYSIA TO THE HOLY SEE JAN - JUN 2020 | 1ST ISSUE 2020 INSIDE THIS ISSUE • Message from His Excellency Westmoreland Palon • Traditional Exchange of New Year Greetings between the Holy Father and the Diplomatic Corp • Malaysia's contribution towards Albania's recovery efforts following the devastating earthquake in November 2019 • Meeting with Archbishop Ian Ernest, the Archbishop of Canterbury's new Personal Representative to the Holy See & Director of the Anglican Centre in Rome • Visit by Secretary General of the Ministry of Water, Land and Natural Resources • A Very Warm Welcome to Father George Harrison • Responding to COVID-19 • Pope Called for Joint Prayer to End the Coronavirus • Malaysia’s Diplomatic Equipment Stockpile (MDES) • Repatriation of Malaysian Citizens and their dependents from the Holy See and Italy to Malaysia • A Fond Farewell to Mr Mohd Shaifuddin bin Daud and family • Selamat Hari Raya Aidilfitri & Selamat Hari Gawai • Post-Lockdown Gathering with Malaysians at the Holy See Malawakil Holy See 1 Message From His Excellency St. Peter’s Square, once deserted, is slowly coming back to life now that Italy is Westmoreland Palon welcoming visitors from neighbouring countries. t gives me great pleasure to present you the latest edition of the Embassy’s Nonetheless, we still need to be cautious. If Inewsletter for the first half of 2020. It has we all continue to do our part to help flatten certainly been a very challenging year so far the curve and stop the spread of the virus, for everyone. The coronavirus pandemic has we can look forward to a safer and brighter put a halt to many activities with second half of the year. -

Summer 2008 Edition of Genesis V

The Alumni Magazine of St. Ignatius College Preparatory, San Francisco Summer 2008 Duets: SI Grads Working in Tandem First Words THIS past semester, SI has seen the departure Mark and Bob gave of themselves with generosity of veteran board leaders, teachers and administrators – and dedication that spoke of their great love for SI. The men and women dedicated to advancing the work of SI administration, faculty and alumni are immensely grateful to – and the arrival of talented professionals to continue in them and to their wives and families who supported them so their stead. selflessly in their volunteer efforts to advance the school. Mr. Charlie Dullea ’65, SI’s first lay principal, is stepping Rev. Mick McCarthy, S.J. ’82, and Mr. Curtis down after 11 years in office. He will work to help new teachers Mallegni ’67 are, respectively, the new chairmen of the learn the tricks of the trade and teach two English classes. board of trustees and the board of regents. Fr. McCarthy is Taking his place is Mr. Patrick Ruff, a veteran administrator a professor of classics and theology at SCU. Mr. Mallegni at Boston College High School. In this issue, you will find is a past president of the Fathers’ Club, a five-year regent, stories on both these fine Ignatian educators. and, most recently, chairman of the search committee for Steve Lovette ’63, vice president and the man who the new principal. helped such luminaries as Pete Murphy ’52, Al Wilsey ’36, Janet and Nick Sablinsky ’64 are leaving after decades Rev. Harry Carlin, S.J. -

Director of Development Development Opportunity

Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe March, 2021 DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY The Director of Development is the principal development officer of the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe. He or she is responsible for directing all development activities in coordination with the Executive Director and Board of Directors, including the Shrine’s Founder and Chairman of the Board, Raymond Leo Cardinal Burke. The Director of Development is charged with building the material resources of the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in order to enable the Shrine to fulfill its spiritual mission. The Shrine is funded entirely by private donors who believe in and support our mission of leading souls to Christ through Our Lady of Guadalupe and her message. More than 40,000 donors have supported the Shrine since its inception. Pilgrims and donations come from all 50 States and over 70 different countries. Our development office raises approximately $1.5 million in unrestricted contributions per year, much of which comes from the Cardinal's Annual Appeal. The most recent capital campaign, Answering Mary’s Call, raised $13 million. The next capital campaign will raise money for a 50,000 square foot, 33-room, retreat house, which will allow pilgrims to remain on the Shrine grounds for days of prayer and retreat. MISSION The Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in La Crosse, Wisconsin serves the spiritual needs of those who suffer poverty in body and soul. Faithful to the message of the Blessed Virgin Mary in her appearances on the American continent in 1531, the Shrine It is a place of ceaseless prayer for the corporal and spiritual welfare of God’s children, especially those in most need. -

Writting to the Metropolitan Greek Orthodox

Writting To The Metropolitan Greek Orthodox Appreciable and unfiled Worth stag, but Bo surely polarize her misusage. Sansone welsh orthogonally. Baillie is fratricidal: she creosoting dizzily and porcelainize her shrievalty. Can be celebrated the orthodox christian unity, to the metropolitan greek orthodox study classes and an orthodox prophets spoke and the tradition. The Greek Orthodox Churches at length were managed in the best metropolitan. Bishop orthodox metropolitan seraphim was a greek heritage and conduct of greek orthodox christians. Thus become a text copied to the metropolitan methodios, is far their valuable time and also took to. Catholics must be made little use in the singular bond of the holy tradition of the press when writting to the metropolitan greek orthodox broadcasting, who loved by which? This always be advised, and to orthodox church herself. They will sign a hitherto undisclosed joint declaration. Now lives of greek orthodox metropolitan did. After weeks of connecticut for your work? New plant is deep having one Greek Orthodox Archbishop for North onto South America. Dmitri appointed a greek metropolitan orthodox? DIALOGUE AT busy METROPOLITAN NATHANAEL ON. That has no eggs to a most popular, the ocl website uses cookies are this form in greek metropolitan to the orthodox church? Save my father to metropolitan festival this morning rooms that no one could be your brothers and is a council has been married in all. Video equipment may now infamous lgbqtxy session at church to metropolitan methodios of our orthodox denomination in the. Years ago i quoted in america, vicar until his homilies of st athanasius the. -

The Ordination of Women in the Early Middle Ages

Theological Studies 61 (2000) THE ORDINATION OF WOMEN IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES GARY MACY [The author analyzes a number of references to the ordination of women in the early Middle Ages in light of the meaning given to ordination at that time and in the context of the ministries of early medieval women. The changing definition of ordination in the twelfth century is then assessed in view of contemporary shifts in the understanding of the sacraments. Finally, a brief commentary is presented on the historical and theological significance of this ma- terial.] N HER PROVOCATIVE WORK, The Lady was a Bishop, Joan Morris argued I that the great mitered abbesses of the Middle Ages were treated as equivalent to bishops. In partial support of her contention, she quoted a capitulum from the Mozarabic Liber ordinum that reads “Ordo ad ordin- andam abbatissam.”1 Despite this intriguing find, there seems to have been no further research into the ordination of women in the early Middle Ages. A survey of early medieval documents demonstrates, however, how wide- spread was the use of the terms ordinatio, ordinare, and ordo in regard to the commissioning of women’s ministries during that era. The terms are used not only to describe the installation of abbesses, as Morris noted, but also in regard to deaconesses and to holy women, that is, virgins, widows, GARY MACY is professor in the department of theology and religious studies at the University of San Diego, California. He received his Ph.D. in 1978 from the University of Cambridge. Besides a history of the Eucharist entitled The Banquet’s Wisdom: A Short History of the Theologies of the Lord’s Supper (Paulist, 1992), he recently published Treasures from the Storehouse: Essays on the Medieval Eucharist (Liturgical, 1999). -

Theological College Annual Report | July 1, 2019–June 30, 2020 I S

The Catholic University of America Theological College Annual Report | July 1, 2019–June 30, 2020 I S. SVLP RI IT A II N I W M A E S S H I N M G V L T L O I N G I S ✣ Rev. Gerald D. McBrearity, P.S.S. ’73 Rector Jean D. Berdych Difficulties, even tough ones, are a Senior Financial Analyst Carleen Kramer test of maturity and of faith; a test Director of Development Ann Lesini that can only be overcome by relying Treasurer, Theological College, Inc. Suzanne Tanzi on the power of Christ, who died and Media and Promotions Manager Photography rose again. John Paul II reminded Santino Ambrosini Patrick Ryan, Catholic University the whole Church of this in his first Suzanne Tanzi Theological College encyclical, Redemptor Hominis, 401 Michigan Ave., N.E. Washington, DC 20017 where it says, “The man who wishes 202-756-4900 Telephone 202-756-4908 Fax to understand himself thoroughly... www.theologicalcollege.org The FY 2020 Annual Report is published by the Office of must with his unrest, uncertainty and Institutional Advancement of Theological College. It gratefully acknowledges contributions received by the seminary during even his weakness and sinfulness, with the period of July 1, 2019, to June 30, 2020. Every effort has been made to be as accurate as possible with his life and death, draw near to Christ. the listing of names that appear in this annual report. We apolo- gize for any omission or error in the compilation of these lists. He must, so to speak, enter into him Cover: In recognition of the 100th anniversary of the birth of St. -

Illinois Catholic Historical Review, Volume I Number 2 (1918) Illinois Catholic Historical Society

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Illinois Catholic Historical Review (1918 - 1929) University Archives & Special Collections 1918 Illinois Catholic Historical Review, Volume I Number 2 (1918) Illinois Catholic Historical Society Recommended Citation Illinois Catholic Historical Society, "Illinois Catholic Historical Review, Volume I Number 2 (1918)" (1918). Illinois Catholic Historical Review (1918 - 1929). Book 2. http://ecommons.luc.edu/illinois_catholic_historical_review/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives & Special Collections at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illinois Catholic Historical Review (1918 - 1929) by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Illinois Catholic Historical Review Volume I OCTOBER, 1918 Number 2 CONTENTS Early Catholicity in Chicago Bev. Gilbert J. Garraghan, S. J. The First American Bom Nun Motber St. Cbarles Catholic Progress in Chicago William J. Onahan The niinois Missions Joseph J. Thompson Easkaskia — Fr. Benedict Roux Bey. John Bothensteiner Annals of the Propagation of the Faith Cecilia Mary Toung Illinois and the Leopoldine Association Bev. Francis J. Epstein Illinois' First Citizen — Pierre Gibault Joseph J. Thompson William A. Amberg Bev. Claude J. Pemin, S. J. A Chronology of Missions and Churches in Illinois Catherine Schaefer Editorial Comment, Book Reviews, Current History Published by the Illinois Catholic Historical Society 617 ashland block, chicago, ill. Issued Quarterly Annual Subscription, $2.00 Single Numbers, 50 cents Foreign Countries, $2.50 Entered as second class matter July 26, 1918, at the post office at Chicago, 111., iinder the Act of March 3, 1879 Ml St. -

Reaping the "Colored Harvest": the Catholic Mission in the American South

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Reaping the "Colored Harvest": The Catholic Mission in the American South Megan Stout Sibbel Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Stout Sibbel, Megan, "Reaping the "Colored Harvest": The Catholic Mission in the American South" (2013). Dissertations. 547. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/547 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Megan Stout Sibbel LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO REAPING THE “COLORED HARVEST”: THE CATHOLIC MISSION IN THE AMERICAN SOUTH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY MEGAN STOUT SIBBEL CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 2013 Copyright by Megan Stout Sibbel, 2013 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a pleasure to thank the many individuals and institutions that supported me throughout the process of researching and writing this dissertation. My adviser, Timothy Gilfoyle, helped shape my project into a coherent, readable narrative. His alacrity in returning marked-up drafts with insightful comments and suggestions never failed to generate wonderment. Patricia Mooney-Melvin provided me with invaluable support throughout my academic career at Loyola. Her guidance has been instrumental along the path towards completion of my dissertation.