The History Story of the Railway At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fleet Accessibility Information

Fleet accessibility information Fleet accessibility information KEY This key is for the following table. DAC – Dedicated accessible carriage with space for wheelchair and user ST – Standard toilet AT – Accessible toilet (with area to transfer, colour contrasting features, support rails and call for aid) AI – Aural information VI – Visual information PS – Priority seats AS – Accessible signage on outside of train SAA – Scooter/mobility aid acceptance BR – Boarding ramp Great Northern GATWICK SOUTHERN ThamesLink EXPRESS WE’RE WITH YOU December 2020 Class Brand Routes DAC ST of train Entire Southern network excluding Uckfield route and Southern 377 Yes Yes Ashford to Hastings (Marsh Link). London Bridge to Uckfield and Southern 171 Ashford to Yes Yes Hastings (Marsh Link) services Brighton to Seaford, Southern 313/2 Yes No Portsmouth and Ore Southern metro services from Southern 455 * Yes No London Bridge/ London Victoria All Gatwick Express services Gatwick 387/2 including some Yes Yes Express London to Brighton services * These carriages are fully accessible. For minor technical reasons these trains operate under a derogation from the Department of Transport. Further details are available on request. On-train AT AI VI PS AS SAA BR staff Yes; see Check Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes policy online with staff Yes; see Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes policy online Yes; see No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes policy online Yes; see No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No policy online Yes; see Check Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes policy online with staff Class Brand Routes DAC ST -

Planning Committee Report REPORT

Planning Committee Report REPORT SUMMARY REFERENCE NO - 18/502379/LBC APPLICATION PROPOSAL Listed Building application for proposed upgrade of Network Rail's East Farleigh Level Crossing from a Manned Gated Hand Worked (MGHW) Level Crossing to a Manually Controlled Barrier(s) (MCB) type (Resubmission). ADDRESS East Farleigh Mghw Level Crossing Farleigh Lane Farleigh Bridge East Farleigh Maidstone Kent ME16 9NB RECOMMENDATION – Grant Listed Building Consent SUMMARY OF REASONS FOR RECOMMENDATION for approval The level crossing gates do not form part of the main listing for the East Farleigh railway station; The level crossing gates do not appear to be curtilage listed structures, as they constructed after the 1948; Any harm to the character, integrity and setting of the Listed Building, would be outweighed the public safety benefit; The erection of the new level crossing gates does not require Listed Building Consent. REASON FOR REFERRAL TO COMMITTEE Teston Parish Council wishes to see the application refused and request that the application be reported to Planning Committee for the reasons set out in their consultation response. (Note – The site lies with Barming Parish, not Teston Parish) WARD Barming And PARISH/TOWN APPLICANT Network Rail Teston COUNCIL Barming Infrastructure Limited AGENT Network Rail Infrastructure Limited DECISION DUE DATE PUBLICITY EXPIRY OFFICER SITE VISIT 27/06/18 DATE DATE 22/06/18 01/06/18 RELEVANT PLANNING HISTORY (including appeals and relevant history on adjoining sites): App No Proposal Decision Date 17/506600/LBC Listed Building Consent for the upgrade Withdraw 26/2/201 of the level crossing n 8 15/504142/LBC Listed Building Consent - Replacement of Approved 14/7/201 station roof covering 5 MAIN REPORT 1.0 DESCRIPTION OF SITE 1.01 East Farleigh station lies along Farleigh Lane and just to the north of the River Medway. -

Travel Information

TRAVEL INFORMATION for students travelling to Kent from outside the UK Welcome to Kent! This leaflet and our Getting Started Public transport You can get a Tube map free of charge at website has all the information you You can use public transport to travel to the the information points at airports and train need to ensure a smooth journey to University from Heathrow, Stansted and Gatwick stations, or by visiting tfl.gov.uk/maps your new home at Kent. airports. We suggest that you do not use the licensed For the latest COVID-19 information black taxis that wait outside each airport terminal. concerning London public transport, visit They are priced using the taxi meter and are usually tfl.gov.uk/campaign/coronavirus?intcmp=63016 very expensive. Keep informed and stay safe For the Canterbury campus while travelling For details on how to book a taxi in advance of Heathrow – London St Pancras – Canterbury West Please be aware that UK Government arrival, please see www.kent.ac.uk/getting-started • Take the Piccadilly line (dark blue on the guidelines surrounding COVID-19 are /international-students Tube map) from Heathrow to King’s Cross subject to change. Routes and timetables St Pancras, (approximately 45 minutes). King’s are also subject to change by operators. Travel by train to the campuses Cross St Pancras Tube station leads directly into from Heathrow airport St Pancras International and the route is clearly Remember to continually check the status of You can travel from Heathrow to both the signposted throughout the Tube station. your journey and ensure you’re familiar with Canterbury and Medway campuses by train. -

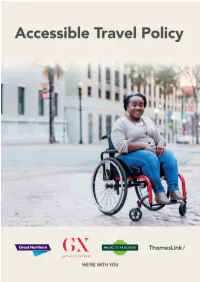

Accessible Travel Policy Document (Large Print

Accessible Travel Policy Great Northern GATWICK SOUTHERN ThamesLink EXPRESS WE’RE WITH YOU 1 Contents 3 A. Commitments to providing assistance 6 A.1 Booking and providing assistance 15 A.2 Information Provision 26 A.3 Ticketing & fares 30 A.4 Alternative accessible transport 32 A.5 Scooters & mobility aids 34 A.6 Delays, disruption and emergencies 36 A.7 Station facilities 38 A.8 Redress 39 B. Strategy and management 39 B.1 Strategy 39 B.2 Management arrangements 42 B.3 Monitoring & evaluation 46 B.4 Access improvements 48 B.5 Working with disabled customers, local communities and local authorities 51 B.6 Staff training 2 A. Commitments to providing assistance Govia Thameslink Railway (GTR) is the parent company for the following train companies. It runs the largest rail network in the country, operating services across the south-east of England under the following brands: Southern Extensive network from London to stations across Sussex and Surrey, the south coast and suburban ‘metro’ services across south London and to Milton Keynes via Watford Junction. Gatwick Express Direct services between London Victoria and Gatwick Airport (and some services towards Brighton). Thameslink Network of services linking many stations north of London such as Bedford, Cambridge, Peterborough, St Albans with destinations south of the River Thames via St Pancras International such as London Bridge, East Croydon, Sutton, Gatwick Airport, Brighton, Horsham and Rainham (Kent). Great Northern Services from London King’s Cross to Peterborough, King’s Lynn via Cambridge and suburban services from Moorgate towards Hertford North, Welwyn Garden City and Stevenage. -

Class 465/466 Enhancement Pack Volume 1

Class 465/466 Enhancement Pack Volume 1 Contents How to Install ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Liveries ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Keyboard Controls .................................................................................................................................. 8 Features ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Variations ............................................................................................................................................... 9 Driver Only Operation (DOO) ....................................................................................................... 12 Wheelslip Protection (WSP) .......................................................................................................... 13 Speed Set ............................................................................................................................................. 14 Accelerometer, Decelerometer & Clock ................................................................................... 14 Player Changeable Destination Display .................................................................................... 15 Automatic Unit Numbering .......................................................................................................... -

18 ROSEMARY PLACE PADDOCK WOOD • KENT 18 Rosemary Place Is a New Single Storey Dwelling with Contemporary Styling

18 ROSEMARY PLACE PADDOCK WOOD • KENT 18 Rosemary Place is a new single storey dwelling with contemporary styling. Located on a small private development, within easy walking distance of the mainline station and town centre. Conveniently situated just a stone’s throw from the centre of Paddock Wood with all it’s amenities. The town is in the heart of Kent, surrounded by attractive Weald farmland with it’s famous hop gardens and many oast houses. Although nestled between pretty Kent villages, it is also a popular commuter town with good links to London, the south coast and also the wider motorway network. Paddock Wood is a central town in this part of the Weald, and has a wide range of shops and facilities. Major high street shopping centres at Tonbridge, Tunbridge Wells and Maidstone are all within half an hour’s drive and provide excellent retail choices. Local leisure facilities include golf clubs at nearby West Malling, and also Putlands Sports and Leisure Centre, which features a beauty room, creche, gym, multi-sports and tennis courts. Floor plan Computer generated image © Westoak Homes Specifications • Single storey dwelling • Traditional construction • Low energy gas fired central heating • Bespoke fitted kitchen with appliances • Feature vaulted ceilings with skylights. • Contemporary styled bathroom • Attractive décor tiles to bathroom and floor • Contemporary grey oak doors • Recessed LED downlights • Cat 5 cabling with USB charge points • Allocated private parking space • Mains smoke alarms, Heat sensors wired and battery backup • 10 year New Homes structural warranty • Leasehold – new 125 year lease, with ground rent and service charge payable • Predicted EPC rating B Transport links Location Site plan Situated close to the M20 and M25 motorways, Paddock Wood has excellent road links. -

London Connections OFF-PEAK RAIL SERVICES

Hertford East St Margarets Interchange Station Aylesbury, Banbury Aylesbury Milton Keynes, Luton Bedford, Stevenage, Letchworth, Welwyn Stevenage Harlow, Bishops Stortford, and Birmingham Northampton, Cambridge, Kings Lynn, Hertford Stansted Airport Limited services (in line colours) Wellingborough, Garden City Ware Rugby, Coventry, Kettering, Leicester, Huntingdon, Peterborough North and Cambridge and The North East Rye Limited service station (in colours) Birmingham and Nottingham, Derby Hatfield Bayford The North West House Escalator link and Sheffield Broxbourne Welham Green Cuffley Airport link Chesham Watford Bricket St Albans ST ALBANS HIGH WYCOMBE Amersham North Wood Abbey Brookmans Park Crews Hill Enfield Town Cheshunt Docklands Light Railway Watford WATFORD Cockfosters Theobalds Tramlink Garston How Park Potters Bar Gordon Hill Wagn Epping Beaconsfield JUNCTION Wood Street Radlett Grove Bus link Hadley Wood Oakwood Enfield Chase Railway Chalfont & Latimer Watford Bush Theydon Bois Croxley Hill UNDERGROUND LINES Seer Green Croxley High Street Silverlink County New Barnet Waltham Cross Green Watford Elstree & Borehamwood Southgate Grange Park Park Debden West Turkey Bakerloo Line Chorleywood Enfield Lock Gerrards Cross Oakleigh Park Arnos Grove Winchmore Hill Street Loughton Central Line Bus Link Stanmore Edgware High Barnet Bushey Southbury Brimsdown Buckhurst Hill Circle Line Denham Golf Club Rickmansworth Mill Hill Broadway Bounds Chiltern Moor Park Carpenders Park Totteridge & Whetstone Chingford Canons Park Burnt New Green -

Tonbridge School Pa / Operations Assistant

TONBRIDGE SCHOOL PA / OPERATIONS ASSISTANT Tonbridge School is one of the leading boys' boarding schools in the country and is highly respected internationally. The school aims to provide a caring and enlightened environment in which the talents of each individual flourish. We encourage boys to be creative, tolerant and to strive for academic, sporting and cultural excellence. Respect for tradition and an openness to innovation are equally valued. A well-established house system at the heart of the school fosters a strong sense of belonging. Tonbridge seeks to celebrate its distinctive mixture of boarders and day boys; this helps to create a unique broadening and deepening of opportunity. We want boys to enjoy their time here, but also to be made aware of their social and moral responsibilities. Tonbridgians should enter into the adult world with the knowledge and self-belief to fulfil their own potential and to become leaders in their chosen field. Equally, we hope to foster a life-long empathy for the needs and views of others; in the words of the great novelist and Old Tonbridgian E.M. Forster: 'Only Connect'. Tonbridge School Job Title: PA / Operations Assistant Reporting to: Commercial and Operations Director (COD) Main Purpose: To provide administrative support for the Commercial and Operations Director, assisting with the effective operation and development of the School’s support functions. To ensure alongside the COD that the School complies with the requirements of relevant regulatory agencies. Main Responsibilities: • To support the Commercial and Operations Director, through the management of his office and support of operational departments/functions (Catering, Porters/Cleaning, Grounds & Gardens, Health & Safety/Security, Reprographics) and commercial activity (Tonbridge School Centre, Recre8 and Events). -

Tonbridge Castle and Its Lords

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 16 1886 TONBRIDGE OASTLE AND ITS LORDS. BY J. F. WADMORE, A.R.I.B.A. ALTHOUGH we may gain much, useful information from Lambard, Hasted, Furley, and others, who have written on this subject, yet I venture to think that there are historical points and features in connection with this building, and the remarkable mound within it, which will be found fresh and interesting. I propose therefore to give an account of the mound and castle, as far as may be from pre-historic times, in connection with the Lords of the Castle and its successive owners. THE MOUND. Some years since, Dr. Fleming, who then resided at the castle, discovered on the mound a coin of Con- stantine, minted at Treves. Few will be disposed to dispute the inference, that the mound existed pre- viously to the coins resting upon it. We must not, however, hastily assume that the mound is of Roman origin, either as regards date or construction. The numerous earthworks and camps which are even now to be found scattered over the British islands are mainly of pre-historic date, although some mounds may be considered Saxon, and others Danish. Many are even now familiarly spoken of as Caesar's or Vespa- sian's camps, like those at East Hampstead (Berks), Folkestone, Amesbury, and Bensbury at Wimbledon. Yet these are in no case to be confounded with Roman TONBEIDGHE CASTLE AND ITS LORDS. 13 camps, which in the times of the Consulate were always square, although under the Emperors both square and oblong shapes were used.* These British camps or burys are of all shapes and sizes, taking their form and configuration from the hill-tops on which they were generally placed. -

Kent Archæological Society Library

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society KENT ARCILEOLOGICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY SIXTH INSTALMENT HUSSEY MS. NOTES THE MS. notes made by Arthur Hussey were given to the Society after his death in 1941. An index exists in the library, almost certainly made by the late B. W. Swithinbank. This is printed as it stands. The number given is that of the bundle or box. D.B.K. F = Family. Acol, see Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Benenden, 12; see also Petham. Ady F, see Eddye. Bethersden, 2; see also Charing Deanery. Alcock F, 11. Betteshanger, 1; see also Kent: Non- Aldington near Lympne, 1. jurors. Aldington near Thurnham, 10. Biddend.en, 10; see also Charing Allcham, 1. Deanery. Appledore, 6; see also Kent: Hermitages. Bigge F, 17. Apulderfield in Cudham, 8. Bigod F, 11. Apulderfield F, 4; see also Whitfield and Bilsington, 7; see also Belgar. Cudham. Birchington, 7; see also Kent: Chantries Ash-next-Fawkham, see Kent: Holy and Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Wells. Bishopsbourne, 2. Ash-next-Sandwich, 7. Blackmanstone, 9. Ashford, 9. Bobbing, 11. at Lese F, 12. Bockingfold, see Brenchley. Aucher F, 4; see also Mottinden. Boleyn F, see Hever. Austen F (Austyn, Astyn), 13; see also Bonnington, 3; see also Goodneston- St. Peter's in Tha,net. next-Wingham and Kent: Chantries. Axon F, 13. Bonner F (Bonnar), 10. Aylesford, 11. Boorman F, 13. Borden, 11. BacIlesmere F, 7; see also Chartham. Boreman F, see Boorman. Baclmangore, see Apulderfield F. Boughton Aluph, see Soalcham. Ballard F, see Chartham. -

A Rail Manifesto for London

A Rail Manifesto for London The new covered walkway linking Hackney Central and Hackney Downs stations creates an interchange which provides a better connection and more journey opportunities March 2016 A Rail Manifesto for London Railfuture1 seeks to inform and influence the development of transport policies and practices nationally and locally. We offer candidates for the 2016 London Mayoral and Assembly elections this manifesto2, which represents a distillation of the electorate’s aspirations for a developing railway for London, for delivery during the next four years or to be prepared for delivery during the following period of office. Executive Summary Recognising the importance of all rail-based transport to the economy of London and to its residents, commuters and visitors alike, Railfuture wishes to see holistic and coherent rail services across all of London, integrated with all other public transport, with common fares and conditions. Achieving this is covered by the following 10 policy themes: 1. Services in London the Mayor should take over. The 2007 transfer of some National Rail services to TfL has been a huge success, transforming some of the worst services in London into some of the best performing. Railfuture believes it is right that the Mayor should take over responsibility for more rail services in London, either by transferring service operation to TfL or by TfL specifying service levels to the operator, and that this must benefit all of London. 2. Improved Services. Frequencies play an important role in the success of metro and suburban train services. We believe that the Mayor should set out the minimum standards of service levels across London seven days per week for all rail services. -

Parish Clerks

CLERKS OF PARISH COUNCILS ALDINGTON & Mrs T Hale, 9 Celak Close, Aldington, Ashford TN25 7EB Tel: BONNINGTON: email – [email protected] (01233) 721372 APPLEDORE: Mrs M Shaw, The Homestead, Appledore, Ashford TN26 2AJ Tel: email – [email protected] (01233) 758298 BETHERSDEN: Mrs M Shaw, The Homestead, Appledore, Ashford TN26 2AJ Tel: email – [email protected] (01233) 758298 BIDDENDEN: Mrs A Swannick, 18 Lime Trees, Staplehurst, Tonbridge TN12 0SS Tel: email – [email protected] (01580) 890750 BILSINGTON: Mr P Settlefield, Wealden House, Grand Parade, Littlestone, Tel: New Romney, TN28 8NQ email – [email protected] 07714 300986 BOUGHTON Mr J Matthews (Chairman), Jadeleine, 336 Sandyhurst Lane, Tel: ALUPH & Boughton Aluph, Ashford TN25 4PE (01233) 339220 EASTWELL: email [email protected] BRABOURNE: Mrs S Wood, 14 Sandyhurst Lane, Ashford TN25 4NS Tel: email – [email protected] (01233) 623902 BROOK: Mrs T Block, The Briars, The Street, Hastingleigh, Ashford TN25 5HUTel: email – [email protected] (01233) 750415 CHALLOCK: Mrs K Wooltorton, c/o Challock Post Office, The Lees, Challock Tel: Ashford TN25 4BP email – [email protected] (01233) 740351 CHARING: Mrs D Austen, 6 Haffenden Meadow, Charing, Ashford TN27 0JR Tel: email – [email protected] (01233) 713599 CHILHAM: Mr G Dear, Chilham Parish Council, PO Box 983, Canterbury CT1 9EA Tel: email – [email protected] 07923 631596 EGERTON: Mrs H James, Jollis Field, Coldbridge Lane, Egerton, Ashford TN27 9BP Tel: