THE MOVEMENT for INDEPENDENT LIVING: a Brief History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Direct Service Professional

Restart, Inc. Direct Service Professional Summary of Organization: Founded in 1986, Restart, Inc. is a Minnesota-based, 501(C3) nonprofit organization that provides Adult Foster Care, Housing with Services and Independent Living Skills Services for more than 225 individuals living with traumatic brain injuries and other disabilities. Our highly qualified staff works with clients to teach strategies and routines that will compensate for abilities that have been compromised by injury. We teach clients activities of daily living and independent living skills, and facilitate reentry into the community through vocational, volunteer, social and leisure activities. We provide a holistic model of service delivery that is built upon each individual’s strengths and abilities. As clients increase their skills, they move along the continuum of independence and reintegrate into the community with purpose and dignity. A brain injury truly cuts across all economic, ethnic, age and gender groups. When a person sustains a brain injury, their life can change in many ways. Personality, behavior, cognition, and memory can be affected. Restart provides the supportive services that give a person the opportunity to start again. Responsibilities: The Direct Support Professional (DSP) is responsible for providing health care, supervision and support services to the residents of Restart, Inc. in accordance with the resident’s Care Plan, Behavior Support Plan and Collaborative Goals. The DSP is responsible for supervision of residents, medication administration, housekeeping and meal preparations for the site and ensuring that the home operates effectively. Qualifications: Must be at least 18 years of age. Completion of Restart, Inc.’s Home Health Aide training and general orientation. -

"Seniors Housing Guide to Fair Housing and ADA Compliance

OO 2016 by the American Seniors Housing Association All rights reserved. The text portions of this work may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recordiny, or by information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publisher. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is distributed with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional services. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. From a Declaration of Principles jointly adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers. Price: $35.00(non-members) Seniors Housing Guide to Fair Housing and ADA Compliance 1 AMERICAN SENIORS HOUSING HansonBridgett ASSOCIATION Living Longer Better 2 Seniors Housing Guide to Fair Housing and ADA Compliance Seniors Housing Guide to Fair Housing and ADA Compliance 3 Introduction .................................................4 Executive Summary...........................................6 Use Of This Guide ............................................8 Federal Anti-Discrimination Statutes ..........................10 I. The Fair Housing Act.............................................. 11 A. The 1968 Act .................................................. 11 B. The Fair Housing Amendments Act Of 1988....................... -

Rules for Level I and II Assisted Living

100 SCOPE ...........................................................................................................................................................3 200 PURPOSE......................................................................................................................................................3 300 DEFINITIONS ..............................................................................................................................................3 400 LICENSURE ...............................................................................................................................................10 401 LICENSING INFORMATION.....................................................................................................................11 402 INITIAL LICENSURE .................................................................................................................................12 403 COMPLIANCE.............................................................................................................................................12 404 APPLICATION, EXPIRATION AND RENEWAL OF LICENSE .............................................................12 405 CHANGE IN OWNERSHIP.........................................................................................................................15 500 ADMINISTRATION ..................................................................................................................................16 501 GOVERNING BODY...................................................................................................................................16 -

Community Living and Participation for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: What the Research Tells Us

Community Living and Participation for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: What the Research Tells Us To: Interested Parties From: The Association of University Centers on Disabilities (AUCD) and the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) Re: Community Living and Participation for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Date: July 24, 2015 Sunday, July 26th is the 25th Anniversary of the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). As he signed the law on the south lawn of the White House, President George H. W. Bush, surrounded by people with disabilities and members of Congress, closed his remarks by stating, “Let the shameful wall of exclusion come tumbling down.” Despite great advances in physical access and technology that have made schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods more accessible, there continue to be barriers to equal opportunity, full participation, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency for all people with disabilities. AUCD supports and promotes a national network of university-based interdisciplinary programs to advance policies and practices that improve the health, education, social, and economic well-being of all people with developmental and other disabilities, their families, and their communities. AAIDD is a national organization that promotes progressive policies, sound research, effective practices, and universal human rights for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Established in 1876, AAIDD is the oldest and largest professional society in the US concerned with intellectual and developmental disabilities. On this 25th anniversary, we are releasing the attached paper, based on over 50 years of research, to describe how AUCD and AAIDD think the next 25 years of the ADA should translate into access, opportunity, and support for people with disabilities. -

RN Delegation 2018

8/13/2018 MEDICATION ASSISTANCE, ADMINISTRATION AND RN DELEGATION Texas Assisted Living Association April, 2015 Objectives • Understand the BON rule for RN delegation in AL— rule 225. • State the requirements for RN delegation, including assessment, training, documentation, and supervision. • Understand the AL regulations for medication assistance, supervision, and administration in AL. • Understand the process for delegation of medication administration in assisted living. The essence of delegation... “But in both (hospitals and private houses), let whoever is in charge keep this simple question in her head, (not, how can I always do this right thing myself, but) how can I provide for this right thing to be always done? Florence Nightingale 1 8/13/2018 Definitions • Client—term to indicate who will receive care—our resident • Client’s Responsible Adult—CRA, an individual chosen by the client who is willing and able to participate in decisions about the overall management of the client’s healthcare • Unlicensed Assistive Personnel—UAP, an individual not licensed as a healthcare provider Rule 225.4 • Delegation—a registered nurse authorizes an unlicensed person to perform tasks of nursing care in selected situations and indicates that authorization in writing. • Delegation is a process that includes the nursing assessment of a client in a specific situation, evaluation of the ability of the unlicensed persons, teaching the task, ensuring supervision of the unlicensed persons and re-evaluating the task at regular intervals. Rule 225.4 (6) • Supervision—a process of directing, guiding, and influencing the outcome of an individual’s performance of an activity. • Assign—describes the distribution of work that each staff member is responsible for during a given shift or work period. -

Transition Guide to Postsecondary Education and Employment for Students and Youth with Disabilities, Washington, D.C., 2017

A TRANSITION GUIDE TO POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION AND EMPLOYMENT FOR STUDENTS AND YOUTH WITH DISABILITIES OFFICE OF SPECIAL EDUCATION AND REHABILITATIVE SERVICES UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION REVISED MAY 2017 U.S. Department of Education Betsy DeVos Secretary Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services Ruth Ryder Delegated the duties of the Assistant Secretary for Special Education and Rehabilitative Services May 2017 Initially issued January 2017 This report is in the public domain. Authorization to reproduce it in whole or in part is granted. While permission to reprint this publication is not necessary, the citation should be: U.S. Department of Education (Department), Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, A Transition Guide to Postsecondary Education and Employment for Students and Youth with Disabilities, Washington, D.C., 2017. To obtain copies of this report: Visit: www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/osers/transition/products/postsecondary-transition-guide-2017.pdf On request, this publication is available in alternate formats, such as Braille, large print, or computer diskette. For more information, please contact the Department’s Alternate Format Center at 202-260-0852 or 202-260-0818. All examples were prepared by American Institutes for Research under contract to the Department’s Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSERS) with information provided by grantees and others. The examples provided in this guide do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department. The Department has not independently verified the content of these examples and does not guarantee accuracy or completeness. Not all of the activities described in the examples are necessarily funded under Parts B or D of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) or the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Rehabilitation Act), as amended by Title IV of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). -

Innovative Independent Living Project Manual

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "#$%!&'(()*+%!*,!-./$)/0!-1'2!! 34%!5+%6%+#/$!7'./$#8)'/! ! 34%!9)++)%!:';+#/$!<8%--%%!7#2)+,!7./$! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! =1)88%/!*,! >%#//%!<,$%/(81)?@%1! 9%84#/,!:)8%!A%((%+! "#,!BCDD! !""#$%&'$()!"*(+("*("&),'$'"-)./#0(1&)2%"3%4) ) ! ) ) ') !""#$%&'$()!"*(+("*("&),'$'"-)./#0(1&)2%"3%4) ! ! "#$%#&'()*+!$,)-!'.#!/,)0#&'!12*23#,«! When we EHJDQWKH,,/3,KDGDYLVLRQRIZKDWQHHGHGWREHGRQHEXWGLGQ¶WUHDOL]H how difficult it would be to accomplish. The project time frame went from eighteen months to over three years as the huge task became clearer. Families struggled with whether or not they could make their own dreams of an independent home for their son or daughter a reality. Some tried for a while, and then life circumstances (family illness, the economic recession, job changes, etc.) happened and they dropped out. Many simply could not find other compatible families with whom to partner. Other families discovered what we were attempting to do and asked to be part of it. In the end, because we were trying to meet our project schedule, we went forward with only seven families who ZHUH³UHDG\QRZ´DQGZKREHOLHYHGLQWKHFRQFHSWEHKLQGWKLVSURMHFWWKDW with the right tools, training and technology, one can create safe and affordable independent community based homes for persons with developmental disabilities. This manual is for the hundreds of others with whom I have talked that want to create a home for their own children. Most are family members who want to be sure their child or sibling will be safe and happy when they can no longer care for him or her. They all worry about things like how to access the support that might be necessary, where the home will be, how to find compatible roommates and families, how to pay for it all, how to find out the rules for government benefits, etc. -

HOUSE AMENDMENT Bill No. CS/HB 7105, 1St Eng. (2014) Amendment No

HOUSE AMENDMENT Bill No. CS/HB 7105, 1st Eng. (2014) Amendment No. CHAMBER ACTION Senate House . 1 Representative Brodeur offered the following: 2 3 Amendment to Amendment (243198) (with title amendment) 4 Remove lines 5-180 of the amendment and insert: 5 Section 2. Section 627.64194, Florida Statutes, is created 6 to read: 7 627.64194 Coverage for orthotics and prosthetics and 8 orthoses and prostheses.—Each accident or health insurance 9 policy issued, amended, delivered, or renewed in this state on 10 or after January 1, 2015, which provides medical coverage that 11 includes physician services in a physician's office and that 12 provides major medical or similar comprehensive type coverage 13 must evaluate and review coverage for orthotics and prosthetics 14 and orthoses and prostheses as those terms are defined in s. 927221 Approved For Filing: 5/2/2014 7:55:28 PM Page 1 of 115 HOUSE AMENDMENT Bill No. CS/HB 7105, 1st Eng. (2014) Amendment No. 15 468.80. Such evaluation and review must compare the coverage 16 provided under federal law by health insurance for the aged and 17 disabled pursuant to 42 U.S.C. ss. 1395k, 1395l, and 1395m and 18 42 C.F.R. ss. 410.100, 414.202, 414.210, and 414.228, and as 19 applicable to this section. 20 (1) The insurance policy may require recommendations for 21 orthotics and prosthetics and orthoses and prostheses in the 22 same manner that prior authorization is required for any other 23 covered benefit. 24 (2) Recommended benefits for orthoses or prostheses are 25 limited to the most appropriate model that adequately meets the 26 medical needs of the patient as determined by the insured's 27 treating physician. -

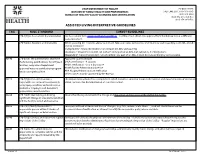

Assisted Living Interpretive Guidelines

UTAH DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH PO BOX 144103 DIVISION OF FAMILY HEALTH AND PREPAREDNESS SALT LAKE CITY, UT 84114-4103 BUREAU OF HEALTH FACILITY LICENSING AND CERTIFICATION (801) 273-2994 (800) 662-4157 toll free (801) 274-0658 Fax ASSISTED LIVING INTERPRETIVE GUIDELINES TAG RULE STANDARD SURVEY GUIDELINES 270-3(2)(a)- Assessment documentation See Assessment form www.health.utah.gov/hflcra . Facilities must obtain pre-approval from the Bureau to use a different assessment form. 270-3(2)(b) Activities of Daily Living When assessing the residents ability to perform ADL's surveyors will observe and interview staff regarding each ADL and the level of assistance: "Independent" means the resident can perform the ADL without help. "Assistance" means the resident can perform some part of an ADL, but cannot do it entirely alone. "Dependent" means the resident cannot perform any part of an ADL; it must be done entirely by someone else. A0140 270-6(1)(f) The administrator shall have Approved courses include: the following qualifications: for all Type II UALA certification - 4 courses facilities, complete a Department AHCA certification - 2 or 3 day course approved national certification program Health Facility Administrator License within six months of hire. AHA Hospital Administrator Certification Other courses may be approved by the Bureau A0215 270-7(2)(e) The administrator is The Department website has a sample form which includes a space for action and response and documentation of corrective responsible to review at least quarterly action. Evaluate for documentation of corrective action. every injury, accident, and incident to a resident or employee and document appropriate corrective action A0220 270-7(2)(f) Maintain log indicating Ensure that the log documents the change and the action and response of the staff at the facility. -

The Need for Centers for Independent Living

Issue Brief The Need for Centers for Independent Living The Problem enters for Independent Living (CIL) play a vital role in helping people with all sorts of disabilities Ccreate and live the life they desire. In Colorado, there are 10 CILs that are federally and/or state certifi ed by the Rehabilitation Services Administration or the state Division of Vocational Rehabilitation (DVR). All ten receive a mix of state and federal and private funding. The CILs face the following challenges in Colorado: • Inadequate fi nancial support with less than $4 million total in funding • Minimal meaningful oversight at the state level • No representation in state level planning activities on disability issues • No leadership to assist CILs in tracking service data consistently across the centers • Lack of oversight and technical assistance to improve service delivery While the State focuses efforts on persons with mental health needs and individuals with intellectual disabilities, individuals with other disabilities often do not receive proper supports and advocacy. Most of these individuals could live independently and work with the training, assistive technology, and benefi ts planning services that are offered by CILs. Persons miss out on the peer support that enables individuals with disabilities to see others who are working, having families and participating in the community. Without these opportunities, people with disabilities can remain trapped in poverty, believing they have little to no talents to contribute. The Independence Center in Colorado What are Centers for Independent Living? Springs CILs, are non-residential organizations that The Independence Center (The IC) is a Center seek to empower others with disabilities for Independent Living located in Colorado through information, role modeling and an Springs. -

Special Ed Transition Handbook.Indd

OKLAHOMA’S TRANSITION EDUCATION HANDBOOK 2011 EDITION S P E C I A L E D U C AT I O N SERVICES OKLAHOMA’S TRANSITION EDUCATION HANDBooK Facilitating Transition of Students with IEPs from School to Further Education, Employment, or Independent Living ———————————————————————————— S pe C I A L E D U C Ati O N S E RV I C es OKLAH O MA STATE DEPARTMENT O F Ed UCATI O N 2 0 1 1 E D iti ON OKLAHOMA’s TransiTION EDUCATION HANDBOOK The information in this handbook is factually supported by the regulations issued in the 2010 Amended Policies and Procedures for Special Education In Oklahoma. Additional factual support came from practices suggested in the 2009 First-Year Special Education Teacher Handbook. The content in the Transition Education Handbook was reviewed and approved by the Oklahoma Transition Council. This Handbook may be copied for no cost for use by pre-service and in-service educators, families of students with disabilities, and related service providers interested in transition education practices. Programs and services dedicated to improving the educational outcomes of students with disabilities may maintain a copy of this Handbook at their website for free distribution. Copyright 2011 Oklahoma State Department of Education ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Oklahoma’s Transition Education Handbook was developed collaboratively through the resources of the Oklahoma Transition Council funded by a grant from the Oklahoma State Department of Education awarded to OU’s Zarrow Center for Learning Enrichment. The Council’s membership included representatives from the Oklahoma State Department of Education, public school directors of special education and special education teachers, service providers, families of students with disabilities, Oklahoma Career Technology Centers, Oklahoma Department of Rehabilitation Services (DRS), and higher education special education programs. -

Choosing an Orthotist Glenn Ham-Rosebrock, CO, Downey, California

INTERNATIONAL POLIO NETWORK POLIO N K N SUMMER 1995 + + + VOL. 11, NO. 3 Sixth International Post-Polio and Independent Living Conference The Battle with Bracing, Part 11: Choosing an Orthotist Glenn Ham-Rosebrock, CO, Downey, California n orthotist specializes in orthopedic appliances, tions are having problems - ankle, knee, hip, even A also known as orthoses. Orthotists study anatomy upper extremity. Range of motion detects joint defor- and physiology, mechanics of movement (kinesiology), mities. Gait analysis is done both before and after lower as well as fabrication of orthoses and prostheses. extremity bracing. Prosthetics deal with replacing missing limbs, while An orthotist should explain what the options are and 1 orthotics provide bracing. A certified orthotist can sug- discuss the types of materials available to fabricate 1 gest how to best duplicate mechanically what is func- the orthoses. The approx- - + .- --.- tionally missing anatomically. imate weight of the differ- + ent approaches should Choose a board certified orthotist. In 1948 the also be discussed. It American board of certification required that orthotists needs to be determined be certified. Anyone already practicing was automati- whether weight and/or cally certified under the "grandfather clause." Those strength is the priority. new in the field were required to take a two-hour written quiz. Today an orthotist must have a bachelor's There are lightweight, sturdy plastics such as I degree and several years of work experience prior /' to his or her exams. The exams consist of a day of polypropolenes or poly- ethylenes. Some braces written, a day of oral, and a couple of days of practical 'gq fabrication.