Pollok & Aytoun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorials of the Browns of Fordell, Finmount and Vicarsgrange

wtmx a m 11 Jinmamt, mb MwTftfytanQL Sra National Library of Scotland *B000069914* / THE BROWISTS OF FORDELL. : o o y MEMORIALS OF THE BROWNS OF FORDELL FINMOUNT AND VICARSGRANGE BY ROBERT RIDDLE STODART AUTHOR OF "SCOTTISH ARMS," ETC. V EDINBURGH ~ Privately Printed by T.& A. Constable, Printers to Her Majesty at the University Press MDCCCLXXXVII Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/memorialsofbrownOOstod . y^u *c ' ?+s ^^f ./ - > Co m? Iftingffolft THE DESCENDANTS OF MR. JOHN BRODNE, MINISTER OF THE GOSPEL AT ABERCORN, 1700-1743, AND CHAPLAIN TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE JEAN, LADY TORPHICHEN, C^ege Genealogical ittemoriaw, THE COMPILATION OF WHICH HAS BEEN A LABOUR OF LOVE EXTENDING OVER MANY YEARS, &re fcetitcateti tig E. R. STODAET. CONTENTS. BROWN OF FORDELL, Etc., Arms, .... 1 Origin, .... 1 o I. William, . o II: Adam, of Carchrony, III. Adam, in Ayrshire, 2 IV. Sir John, Sheriff of Aberdeen, 2 V. John, of Midmar, . 4 VI. John, ,, 5 VII. George, „ 8 VIII. George, Bishop of Dunkekl, 9 VIII. (2) Richard, first of Fordell, 14 IX. Robert, of Fordell, 15 X. John, of Fordell, . 16 . XI. John, younger of Fordell, . 21 XII. John, of Fordell, . 24 XIII. Sir John, of Fordell and Rossie, 26 XIV. John, of Fordell and Rossie, 44 XIV. (2) Antonia, of Fordell and Rossie 44 Vlll CONTENTS. PAGE BROWN OF FINMOUNT, Etc., . \ . 49 of . XI. David, Finmount, . .49 David, of Vicarsgrange, ...... 49 David, „ . .50 50' John, „ . XII. Eobert, of Finmount, ...... 54 XIII. Captain David, of Finmount, ..... 55 XIII. -

Itinerary of Prince Charles Edward Stuart from His

PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME XXIII SUPPLEMENT TO THE LYON IN MOURNING PRINCE CHARLES EDWARD STUART ITINERARY AND MAP April 1897 ITINERARY OF PRINCE CHARLES EDWARD STUART FROM HIS LANDING IN SCOTLAND JULY 1746 TO HIS DEPARTURE IN SEPTEMBER 1746 Compiled from The Lyon in Mourning supplemented and corrected from other contemporary sources by WALTER BIGGAR BLAIKIE With a Map EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1897 April 1897 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................... 5 A List of Authorities cited and Abbreviations used ................................................................................. 8 ITINERARY .................................................................................................................................................. 9 ARRIVAL IN SCOTLAND .................................................................................................................. 9 LANDING AT BORRADALE ............................................................................................................ 10 THE MARCH TO CORRYARRACK .................................................................................................. 13 THE HALT AT PERTH ..................................................................................................................... 14 THE MARCH TO EDINBURGH ...................................................................................................... -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Black's Morayshire Directory, Including the Upper District of Banffshire

tfaU. 2*2. i m HE MOR CTORY. * i e^ % / X BLACKS MORAYSHIRE DIRECTORY, INCLUDING THE UPPER DISTRICTOF BANFFSHIRE. 1863^ ELGIN : PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY JAMES BLACK, ELGIN COURANT OFFICE. SOLD BY THE AGENTS FOR THE COURANT; AND BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. : ELGIN PRINTED AT THE COURANT OFFICE, PREFACE, Thu ''Morayshire Directory" is issued in the hope that it will be found satisfactorily comprehensive and reliably accurate, The greatest possible care has been taken in verifying every particular contained in it ; but, where names and details are so numerous, absolute accuracy is almost impossible. A few changes have taken place since the first sheets were printed, but, so far as is known, they are unimportant, It is believed the Directory now issued may be fully depended upon as a Book of Reference, and a Guide for the County of Moray and the Upper District of Banffshire, Giving names and information for each town arid parish so fully, which has never before been attempted in a Directory for any County in the JTorth of Scotland, has enlarged the present work to a size far beyond anticipation, and has involved much expense, labour, and loss of time. It is hoped, however, that the completeness and accuracy of the Book, on which its value depends, will explain and atone for a little delay in its appearance. It has become so large that it could not be sold at the figure first mentioned without loss of money to a large extent, The price has therefore been fixed at Two and Sixpence, in order, if possible, to cover outlays, Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/blacksmorayshire1863dire INDEX. -

The Continuation, Breadth, and Impact of Evangelicalism in the Church of Scotland, 1843-1900

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. The Continuation, Breadth, and Impact of Evangelicalism in the Church of Scotland, 1843-1900 Andrew Michael Jones A Thesis Submitted to The University of Edinburgh, New College In Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Edinburgh, United Kingdom 2018 ii Declaration This thesis has been composed by the candidate and is the candidate’s own work. Andrew M. Jones PhD Candidate iii Acknowledgements The research, composition, and completion of this thesis would have been impossible without the guidance and support of innumerable individuals, institutions, and communities. My primary supervisor, Professor Stewart J. Brown, provided expert historical knowledge, timely and lucid editorial insights, and warm encouragement from start to finish. My secondary supervisor, Dr. James Eglinton, enhanced my understanding of key cultural and theological ideas, offered wise counsel over endless cups of coffee, and reminded me to find joy and meaning in the Ph.D. -

Black's Morayshire Directory, Including the Upper District of Banffshire

tfaU. 2*2. i m HE MOR CTORY. * i e^ % / X BLACKS MORAYSHIRE DIRECTORY, INCLUDING THE UPPER DISTRICTOF BANFFSHIRE. 1863^ ELGIN : PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY JAMES BLACK, ELGIN COURANT OFFICE. SOLD BY THE AGENTS FOR THE COURANT; AND BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. : ELGIN PRINTED AT THE COURANT OFFICE, PREFACE, Thu ''Morayshire Directory" is issued in the hope that it will be found satisfactorily comprehensive and reliably accurate, The greatest possible care has been taken in verifying every particular contained in it ; but, where names and details are so numerous, absolute accuracy is almost impossible. A few changes have taken place since the first sheets were printed, but, so far as is known, they are unimportant, It is believed the Directory now issued may be fully depended upon as a Book of Reference, and a Guide for the County of Moray and the Upper District of Banffshire, Giving names and information for each town arid parish so fully, which has never before been attempted in a Directory for any County in the JTorth of Scotland, has enlarged the present work to a size far beyond anticipation, and has involved much expense, labour, and loss of time. It is hoped, however, that the completeness and accuracy of the Book, on which its value depends, will explain and atone for a little delay in its appearance. It has become so large that it could not be sold at the figure first mentioned without loss of money to a large extent, The price has therefore been fixed at Two and Sixpence, in order, if possible, to cover outlays, Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/blacksmorayshire1863dire INDEX. -

Correspondence of Sir Robert Kerr, First Earl of Ancram and His Son

iAJ 'w^ Bt.ij . CtMJ* 12.2 CORRESPONDENCE OF Sir Eoijtrt Itrr, jfitst (Bui of Enctam AND HIS SON tlliam, €\)ixii (Buxi of lnt\)mx — CORRESPONDENCE Sir Enlitrt Eerr, jTirst <Eatl of Siuram AND HIS SON illiiim, SCljirtr ®aii ot lotijiatt IN TWO VOLUMES Vol. I. 1616-1649 EDINBURGH: MDCCCLXXV Piinied by R. & R. CLARK, EdMnrgh. TO THE SURVIVING MEMBERS OF €^l)e Bannatpne Club, THESE VOLUMES, CONTAINING THE CORRESPONDENCE OF THE EARLS OF ANCRAM AND LOTHIAN, PRINTED FROM THE ORIGINAL LETTERS AT ARE PRESENTED BY THEIR OBEDIENT SERVANT, May 1875. CONTENTS. VOL. I. PAGE Preface ......... i Memoir of Robert, Earl of Ancram ..... v Memoir of William, Earl of Lothian ..... xlv Genealogical Tables ... .... cxiii Claim of Robert, Lord Kerr of Newbattle, to the Earldom of ROXBURGHE, 1658 ....... Cxi.X Robert Leighton and the Parish Church of Newbattle . cxxii James Kerr, Keeper of the Record.s ..... cxxvii Additions and Corrections ...... cxxix CORRESPONDENCE. 1616-1649 1-2.1 VOL. II. CORRESPONDENCE, 1649-1667 ..... 249-480 Additional Letters— Ancram Letters, 1625-1642 ...... Lothian Letters, 1 631- 166 7 Appendix— No. L Pfalms in Englifli Verfe, by Sir Robert Kerr, Earl of Ancram, 1624 ... 487 No. IL Letters from Dr. Donne, Dean of St. Paul's, to Sir Robert Kerr 507 No. III. Letters from Drummond of Hawthornden to Sir Robert Kerr . 517 No. IV. Accounts for Books and Notes of Paintings purchafed for the Earl of Lothian, 1643-1649 . 524 No. V. Newbattle Abbey and its Library . 532 Index of Letters ........ 543 Index of Names ........ 55° LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. VOL I. Seals of the Rarls of Ancram and Lothian . -

Norman Macleod Famous Scots Series

iliiiiil FAMOUS SCOTS* SERIES* CAVEN LiB.lARY KNOX COLLEGE TORONTO NORMAN MACLEOD FAMOUS SCOTS SERIES The following Volumes are now ready THOMAS CARLYLE. By HECTOR C. MACPIIERSON ALLAN RAMSAY. By OLIPHANT SMEATON HUGH MILLER. By W. KEITH LEASK JOHN KNOX. By A. TAYLOR INNES ROBERT BURNS. By GABRIEL SETOUN THE BALLADISTS. By JOHN GEDDIE RICHARD CAMERON. By Professor HERKLESS SIR JAMES Y. SIMPSON. By EVE BLANTYRE SIMPSON THOMAS CHALMERS. By Professor W. GARDEN BLAIKIE JAMES BOSWELL. By W. KEITH LEASK TOBIAS SMOLLETT. By OLIPHANT SMEATON FLETCHER OF SALTOUN. By G. W. T. OMOND THE BLACKWOOD GROUP. By SIR GEORGE DOUGLAS NORMAN MACLEOD. By JOHN WELLWOOD NORMAN MACLEOD BY JOHN : : WELLWOOD FAMOUS SCOTS: SERIES PUBLISHED BY Q OUPHANT ANDERSON IfFERRIER EDINBVRGH AND LONDON ^ &lt;s&gt; CAViN LIBRARY KNOX COLLEGE TORONTO The designs and ornaments of this volume are by Mr. Joseph Brown, and the printing from the press of Morrison & Gibb Limited, Edinburgh. NOTE MY cordial gratitude is due to Mr. William Isbister best of smokers for allowing me (and that with so good a spirit) to quote from the Memoir of Norman Macleod. The present piece will not have been written in vain, as the saying is, if it sends readers to that entertaining quarry. I have also to thank Mr. J. C. Erskine, Hope Street, Glasgow ( Be calm, Erskine ), for furnishing me with certain letters never before published, specimens of which will be found in the text. The extracts from the Queen s books are made with Her Majesty s gracious permission. J. w. MANSE OF DRAINIE, April 1897. -

Norman Macleod Famous Scots Series

Norman Macleod Famous Scots Series John Wellwood CHAPTER I 1812-1837 DESCENT—BOYHOOD—STUDENT YEARS Nothing astonished Dr. Johnson so much, when he was roving in the Hebrides, as to find men who lived in huts and quoted Latin. These were the ‘gentlemen tacksmen,’ and no more remarkable tenantry was ever seen on any soil. What they did for agriculture I cannot say; as much, perhaps, as their destroyers, who made a solitude and called it sheep: but they had bread to eat and raiment to put on (though they mightsometimes sleep with their feet in the mire), and their praise is that they sent forth a splendid race to the fields of honour. Their sons, scant of cash, yet with the air of nobles, thronged the colleges, nor was there any career in which laurels were not won by men from the mountains and the isles. Picture some judge or general gazing at the ruins of a shieling, and then sneer at the old Highland tacksmen. From this class Norman Macleod was descended. His great-grandfather, the earliest ancestor of whom we have any record, lived in Skye, at Swordale, near Dunvegan Castle, about the middle of last century. The tradition is that he was a good man and the first in his neighbourhood to introduce family worship. His dearest wish was to see his first-born a minister of the Church of Scotland. The estate of the Laird of Macleod was then a sort of feudal Utopia, in which the ruling idea was the advancement of the youth. -

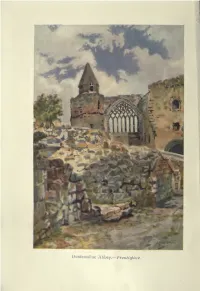

The Fringes of Fife

Uuniermline Ahh^y.—Frojitisptece. THE FRINGES OF FIFE NEW AND ENLARGED EDITION BY JOHN GEDDIE Author ot "The FiiniJes of Edinburjh," etc. Illustrated by Artliur Wall and Louis Weirter, R.B.A. LONDON: 38 Soto Square. W. 1 W. & R. CHAMBERS. LIMITED EDINBURGH: 339 High Street TO GEORGE A WATERS ' o{ the ' Scotsman MY GOOD COLLEAGUE DURING A QUARIER OF A CENTURY FOREWORD *I'll to ¥\ie:—Macl'eth. Much has happened since, in light mood and in light marching order, these walks along the sea- margin of Fife were first taken, some three-and-thirty years ago. The coasts of 'the Kingdom' present a surface hardened and compacted by time and weather —a kind of chequer-board of the ancient and the modern—of the work of nature and of man ; and it yields slowly to the hand of change. But here also old pieces have fallen out of the pattern and have been replaced by new pieces. Fife is not in all respects the Fife it was when, more than three decades ago, and with the towers of St Andrews beckoning us forward, we turned our backs upon it with a promise, implied if not expressed, and until now unfulfilled, to return and complete what had been begun. In the interval, the ways and methods of loco- motion have been revolutionised, and with them men's ideas and practice concerning travel and its objects. Pedestrianism is far on the way to go out of fashion. In 1894 the 'push-bike' was a compara- tively new invention ; it was not even known by the it was still name ; had ceased to be a velocipede, but a bicycle. -

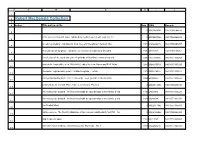

Robert Macdonald Collection 3 4 Author Title, Part No

A B C D E F 1 2 Robert MacDonald Collection 3 4 Author Title, part no. & title Date ISBN Barcode 0 M0019855HL 38011050264616 5 51 beauties of Scottish song : adapted for medium voices with tonic sol-fa / 0 M0006030HL 38011050265076 6 A Celtic miscellany : translations from the Celtic literatures / Kenneth Hur 1971 0140442472 38011050265357 7 A chuidheachd mo ghaoil : laoidean / air an seinn le Cairstiona Sheadha 1990 q8179317 38011050265662 8 A collection of the vocal airs of the Highlands of Scotland : communicated a 1996 1871931665 38011551310264 9 Acts of the Lords ofthe Isles 1336-1493 / edited by Jean Munro and R.W. Munr 1986 0906245079 38011551867255 10 Amannan : sgialachdan goimi / Pòl MacAonghais ... (et al.) 1979 055021402x 38011551310512 11 Am feachd Gaidhealach : ar tir 's ar teanga : lean gu dlùth ri cliù do shinn 1944 w3998157 38011551310850 12 A Mini-Guide to Cornish. Place Names, Dictionary, Phrases 0 M0023438HL 38011050270191 13 Am measg nam bodach : co-chruinneachadh de sgeulachdan is beul-aithris a cha 1938 q3349594 38011551310421 14 Am measg nam bodach : co-chruinneachadh de sgeulachdan is beul-aithris a cha 1938 q3349594 38011551311031 15 [An Dealbh Mhor] 0 M0023413HL 38011551315883 16 An Deo Greine. The Monthly Magazine of An Comunn Gaidhealach. Vol.XV1, No. 0 M0021209HL 38011050266405 17 And it came to pass 1962 b6219267 38011551865341 18 An Inverness miscellany / [edited by Loraine Maclean]. - No.1 1983 0950261238 38011551866331 19 A B C D E F An Inverness miscellany / [edited by Loraine Maclean]. - No.2 1987 0950261262 38011551866349 20 An Leabhar mo`r = The great book of Gaelic / edited by Malcolm Maclean and T 2002 1841952494 38011551311411 21 AN ROSARNACH:AN CEATHRAMH LEABHARBOOK 4. -

A Summer in Skye

#.»•> X 0>vi. i.d>o. (Alkidi h A SUMMER IN SKYE IN TWO VOLUMES / (^ A SUMMER IN SKYE By ALEXANDER SMITH AUTHOR np "a life DRAMA, ETC. VOLUME I. AT,EXANDER STRAHAN, PUBLISHER 148 STRAND, LONDON 1865 CONTENTS OF VOL. I. EDINBURGH, I STIRLING AND THE NORTH, .... 49 OBAN, 77 SKYE AT LAST, ....... 83 AT MR M'IAN'S, .118 A BASKET OF FRAGMENTS, . 191 THE SECOND SIGHT, . .... 260 IN A SKYE BOTHY, 283 A SUMMER IN SKYE. EDINBURGH. QUMMER has leaped suddenly on Edinburgh like a tiger. The air is still and hot above the houses ; but every now and then a breath of east wind startles you through the warm sun- shine— like a sudden sarcasm felt through a strain of flattery—and passes on detested of every organ- ism. But, with this exception, the atmosphere is so close, so laden with a body of heat, that a thunderstorm would be almost welcomed as a re- lief. Edinburgh, on her crags, held high towards the sun —too distant the sea to send cool breezes to street and square— is at this moment an un- comfortable dwelling-place. Beautiful as ever, of course—for nothing can be finer than the ridge /^OL. I. A —; A SUMMER IN SKYE. of the Old Town etched on hot summer azure but close, breathless, suffocating. Great volumes of white smoke surge out of the railway station ; great choking puffs of dust issue from the houses and shops that are being gutted in Princes Street. The Castle rock is gray ; the trees are of a dingy " olive ; languid swells," arm-in-arm, promenade uneasily the heated pavement ; water-carts every- where dispense their treasures ; and the only human being really to be envied in the city is the small boy who, with trousers tucked up, and un- heeding of maternal vengeance, marches coolly in the fringe of the ambulating shower-bath.