4 the Castle of Montella: Stratigraphic Analysis and Material Culture of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N. Purcell, 1997 Introduction The landscape of central Italy has not been intrinsically stable. The steep slopes of the mountains have been deforested–several times in many cases–with consequent erosion; frane or avalanches remove large tracts of regolith, and doubly obliterate the archaeological record. In the valley-bottoms active streams have deposited and eroded successive layers of fill, sealing and destroying the evidence of settlement in many relatively favored niches. The more extensive lowlands have also seen substantial depositions of alluvial and colluvial material; the coasts have been exposed to erosion, aggradation and occasional tectonic deformation, or–spectacularly in the Bay of Naples– alternating collapse and re-elevation (“bradyseism”) at a staggeringly rapid pace. Earthquakes everywhere have accelerated the rate of change; vulcanicity in Campania has several times transformed substantial tracts of landscape beyond recognition–and reconstruction (thus no attempt is made here to re-create the contours of any of the sometimes very different forerunners of today’s Mt. Vesuvius). To this instability must be added the effect of intensive and continuous intervention by humanity. Episodes of depopulation in the Italian peninsula have arguably been neither prolonged nor pronounced within the timespan of the map and beyond. Even so, over the centuries the settlement pattern has been more than usually mutable, which has tended to obscure or damage the archaeological record. More archaeological evidence has emerged as modern urbanization spreads; but even more has been destroyed. What is available to the historical cartographer varies in quality from area to area in surprising ways. -

Nomine a Tempo Determinato Rettificato Aggiornato Al 29 Sett 2020 VENUS

MINISTERO DELL’ISTRUZIONE UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE PER LA CAMPANIA UFFICIO VII - AMBITO TERRITORIALE DI AVELLINO OD / TIPO DATA FINE RIS. CLASSE COD.SCUOLA SCUOLA OF POSTO CATT DOCENTE INDIVIDUATO CODICE FISCALE SUPPLENZA GRAD. posiz. punt. PREC. A001 AVMM86601T Baiano OF AN Catt. MARINO ALFONSO BERNARDO MRNLNS63M20B590L 30/06/2021 GPS 1 4 45,00 A001 AVMM871019 Caposele OF AN Catt. STELLA EMILIANO STLMLN78M29A509I 30/06/2021 GPS 1 2 67,00 A001 AVMM871019 Caposele OF AN Catt. Chiusano S.Domencio completa con coe 14+4 A001 AVMM851014 Avellino Dante" OF AN A001 AVMM807012 Flumeri OF AN Catt. A001 AVMM877018 Lacedonia OF AN Catt. coe 12+6 A001 AVMM877018 Lacedonia completa con Volturara Irp. OF AN A001 AVMM86801D Montella completa con Nusco OD AN coe 12+6 Montoro Inferiore completa con A001 AVMM87901X Montoro Superiore OF AN coe 12+6 A001 AVMM807012 Flumeri AN A022 AVMM848018 Altavilla Irpina OD AN Catt. PECORARO RAFFAELLA PCRRFL78L50F912R 31/08/2021 GPS 2^FASC. 35 102,00 A022 AVMM848018 Altavilla Irpina OD AN Catt. ANGELASTRO ANTONELLA NGLNNL77H62A509E 31/08/2021 GPS 2^FASC. 36 102,00 A022 AVMM86201E Ariano Irpino "Cardito" OF AN Catt. MOSCARITOLO ANGELINA MSCNLN63D67E206N 30/06/2021 GPS 2^FASC. 13 138,00 A022 AVMM849047 Ariano Irpino "Cvotta" OD AN Catt. STOPPA MICHELA STPMHL88S53A783B 31/08/2021 GPS 2^FASC. 47 96,00 A022 AVMM849047 Ariano Irpino "Cvotta" OD AN Catt. A022 AVMM86301A Ariano Irpino "Lusi" OD AN Catt. Ariano Irpino "Lusi" completa con coe 13+5 A022 AVMM86301A Ariano "Calvario" OD AN A022 AVCT700003 CPIA Eda Ariano Irpino OD AN Catt. -

Progetto CARG Per Il Servizio Geologico D’Italia - ISPRA: F

I S P R A Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale SERVIZIO GEOLOGICO D’ITALIA Organo Cartografi co dello Stato (legge n°68 del 2.2.1960) NOTE ILLUSTRATIVE della CARTA GEOLOGICA D’ITALIA alla scala 1:50.000 foglio 450 SANT’ANGELO DEI LOMBARDI A cura di: T. S. Pescatore1†, F. Pinto1 Con contributi di: P. Galli2 (Sismicità e Strutture Sismogeniche) S. I. Giano3 (Geologia del Quaternario e Geomorfologia) R. Quarantiello1 (Geologia Applicata) M. Schiattarella3 (Tettonica e Morfotettonica) PROGETTORedazione scientifica: M.L. Putignano4 1 Dipartimento di Scienze per la Biologia, Geologia e l’Ambiente, Università degli Studi del Sannio - Benevento 2 Dipartimento di Protezione Civile Nazionale - Roma 3 Dipartimento Scienze Geologiche, Università degli Studi della Basilicata - Potenza 4 Istituto di Geologia Ambientali e Geoingegneria - IGAG - CNR - RomaCARG CNR Ente realizzatore: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche NoteIllustrative F450_S.Angelo dei Lomabardi_17_01_2020_cc.indd 1 17/01/2020 16:20:53 Direttore del Servizio Geologico d’Italia - ISPRA: C. Campobasso Responsabile del Progetto CARG per il Servizio Geologico d’Italia - ISPRA: F. Galluzzo Responsabile del Progetto CARG per il CNR: R. Polino (IGG), fino al 2009, P. Messina (IGAG) Gestione operativa del Progetto CARG per il Servizio Geologico d’Italia - ISPRA: M.T. Lettieri per il Consiglo Nazionale delle Ricerche - CNR: P. Messina (IGAG) PER IL SERVIZIO GEOLOGICO D’ITALIA - ISPRA: Revisione scientifica: R. Di Stefano (†), A. Fiorentino, F. Papasodaro, P. Perini Coordinamento cartografico: D. Tacchia (coord.), S. Grossi Revisione informatizzazione dei dati geologici: L. Battaglini, R. Carta, A. Fiorentino (ASC) Coordinamento editoriale: D. Tacchia (coord.), S. Grossi PER IL CONSIGLIO NAZIONALE DELLE RICERCHE: Funz. -

Lessons Learnt from Landslide Disasters in Europe

NEDIES PROJECT Lessons Learnt from Landslide Disasters in Europe Edited by Javier Hervás 2003 EUR 20558 EN ii NEDIES Series of EUR Publications Alessandro G. Colombo (Editor), 2000. NEDIES Project - Lessons Learnt from Avalanche Disasters, Report EUR 19666 EN , 14 pp. Alessandro G. Colombo (Editor) 2000. NEDIES Project - Lessons Learnt from Recent Train Accidents, Report EUR 19667 EN, 28 pp. Alessandro G. Colombo (Editor), 2001. NEDIES Project - Lessons Learnt from Tunnel Accidents, Report EUR 19815 EN, 48 pp. Alessandro G. Colombo and Ana Lisa Vetere Arellano (Editors), 2001. NEDIES Project - Lessons Learnt from Storm Disasters, Report EUR 19941 EN., 45 pp. Chara Theofili and Ana Lisa Vetere Arellano (Editors), 2001. NEDIES Project - Lessons Learnt from Earthquake Disasters that Occurred in Greece, Report EUR 19946 EN, 25 pp. Alessandro G. Colombo and Ana Lisa Vetere Arellano (Editors), 2002. NEDIES Project - Lessons Learnt from Flood Disasters, Report EUR 20261 EN, 91 pp. Alessandro G. Colombo, Javier Hervás and Ana Lisa Vetere Arellano, 2002. NEDIES Project – Guidelines on Flash Flood Prevention and Mitigation, Report EUR 20386 EN, 64 pp. Ana Lisa Vetere Arellano, 2002. NEDIES Project – Lessons Learnt from Maritime Disasters, Report EUR 20409 EN, 30 pp. Alessandro G. Colombo and Ana Lisa Vetere Arellano (Editors). Proceedings NEDIES Workshop - Learning our Lessons: Dissemination of Information on Lessons Learnt from Disasters (in press). Ana Lisa Vetere Arellano (Editor). Lessons Learnt from Forest Fire Disasters (in press). Javier Hervás (Editor). Recommendations to deal with Snow Avalanches in Europe (in press). iii LEGAL NOTICE Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. -

Lioni Bagnoli Irpino Nusco Caposele Calabritto Acerno Montella

SP286 SP 149 FS SP 102 Comune di Bagnoli Irpino SP279 SS7 Provincia di Avellino SP260 SS7 SP220 SP59 Montemarano FS Cassano Irpino SS dir C SP154 SP279 SS164 SP59 FS SSBIS-Ofantina FS SP33 SS Fondo Valle Sele IL SISTEMA DELLE CONOSCENZE SP152 SP115 SSBIS-Ofantina FS SP238 A ANALISI TERRITORIALE FS SS7 Tavola A1 INQUADRAMENTO TERRITORIALE Supporto tecnico-scientifico Dipartimento di Ingegneria Civile Università degli studi di Salerno Gruppo di ricerca in Tecnica e Pianificazione Urbanistica Nusco SS574 Responsabile scientifico prof. ing. Roberto Gerundo Coordinatore tecnico prof. ing. Michele Grimaldi, PhD SS7 Responsabile operativo dott ing. Alessandra Marra Montella * Sindaco avv. Teresa Anna Di Capua Coordinatore della progettazione arch. Ciriaco Lanzillo * SS574 SS164 SP43 SS165 Lioni SP158 scala 1:25000 Convenzione del 12.07.2017 marzo 2019 FS SS368 SP33 SP95 SS368 Legenda FS SS368 * SP152 limiti comunali Bagnoli * limite comunale Bagnoli Irpino Caposele limiti provinciali Irpino SS368 SS164 principali corsi d'acqua * SS Fondo Valle Sele Sistema insediativo SP152 centri abitati Istat 2011 SS165 nuclei abitati Istat 2011 SS368 SP130 Sistema della mobilità * strade statali SP143 strade regionali strade provinciali * FS ferrovia - percorso mobilità dolce (Avellino-Rocchetta) Sistema produttivo aree industriali (Pip) Calabritto località produttive Istat 2011 SP143 Sistema delle protezioni e delle emergenze Attrezzature sanitarie SP91 SP261 centri storici presidi sanitari centri storici di pregio (fonte: PTCP Provincia di Avellino) Attrezzature -

Residence L'antica Fattoria

Residence L’Antica Fattoria Address: Via Piergolo Sant’Angelo all’Esca (Avellino) Tel. (+39) 0827.73766 web site: www.tenutacavalierpepe.it email: [email protected] Facebook: Tenuta Cavalier Pepe Instagram: @Tenuta_cavalier_pepe Hospitality in the Irpinia vineyards and olive trees Wake up in the tranquil hills of the Calore Valley at L'Antica Fattoria nestled amongst rows of vines and centuries-old olive trees, in one of the major terroirs of Irpinia viticulture. Located in the heart of the Taurasi DOCG production area, in the municipality of Sant'Angelo all'Esca within the vineyards of the Cavalier Pepe estate, a modern and welcoming winery managed by Milena Pepe. The accommodation consists of two independent apartments, both bright and airy offering panoramic views across the Irpinia countryside, each equipped with every comfort. If you are looking for a tranquil and relaxing vacation in the heart of the Taurasi region then L’Antica Fattoria is the perfect location. The recently renovated country house, will immerse you in an extraordinary experience of living in the Irpinia vineyards. Strategically positioned in the heart of the highly revered Irpinia wine region. You will discover one of the premiere areas most suited to the cultivation of Aglianico, Fiano, Coda di Volpe and Falanghina grapes. Within easy walking distance are the Cavalier Pepe estate cellars where you will be guided on a fascinating sensory enological journey through the centuries old vineyards, to the wine-making and bottling rooms and the barrel cellar where you can taste the estate wines. In the immediate vicinity of the estate, perched on a hillside, the winery restaurant will welcome you for lunch or dinner with a tasting menu of typical local products and the traditional Irpinian culinary dishes. -

Which Future for Small Towns? Interaction of Socio-Economic Factors and Real Estate Market in Irpinia

Which future for small towns? Interaction of socio-economic factors and real estate market in Irpinia Fabiana Forte*, Luigi Maffei**, keywords:small towns, Irpinia district, Pierfrancesco De Paola*** socioeconomic dynamics, real estate Abstract In the Italian territory most of small towns, which of research at the Department of Architecture and In- represent about 70% of the municipalities, are char- dustrial Design of University of Campania. In this acterized by “socio-economic marginality” and, perspective, the article, starting from the strategies, among the several reasons, the negative demo- tools and incentives currently available for the safe- graphic dynamics is one of the main causes. This guard and valorization of these territories, highlights phenomenon is particularly evident in the Irpinia dis- the socio-economic dynamics in some small munic- trict, approximately coincident with the province of ipalities of Irpinia, with particular reference to the ef- Avellino, in Campania Region, for a long time subject fects on the real estate market. 1. SMALL TOWNS IN IRPINIA: THE STALL OF empty, with several effects on the real estate market too. NATIONAL STRATEGY But small towns, because poor or depopulated, are also about 600 Italian municipalities with more 5.000 inhabi- “Small towns” constitute a relevant part of the Italian ter- tants (Lupatelli, 2016). Most of them are indeed character- ritory, representing about 70% of the municipalities, with ized by “socio-economic marginality” and, among the sev- a surface covering 55% of the national territory. According eral reasons, there is the negative trend of the population to Legambiente (2016) on a total of 5.497 small towns under 5.000 inhabitants, 2.430 are those who suffer a strong eco- that led to the depletion of human capital, especially nomic and demographic discomfort. -

Ii-Grado-Sostegno

Ministero dell’Istruzione, Ufficio Scolastico Regionale per la Campania Ufficio VII - Ambito Territoriale di AVELLINO DISPONIBILITA' SOSTEGNO 2° GRADO A.S. 2021/22 Natura Codice scuola Scuola N. Posto 1 AVIS028006 DE SANCTIS - D'AGOSTINO AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 1 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 2 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 3 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 4 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 5 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 6 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 7 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 8 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 9 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 10 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 11 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 12 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 13 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 14 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 15 DORIA" AVELLINO I.P.S.S.E.O.A. " MANLIO ROSSI - AVRH04000X 16 DORIA" AVELLINO 1 AVTF070004 ITIS GUIDO DORSO AVELLINO 1 AVPC040003 P COLLETTA AVELLINO ISTITUTO D'ISTRUZ. SUP. "G. -

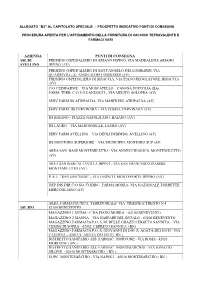

Avalente E Farmaci Vari

ALLEGATO B2 AL CAPITOLATO SPECIALE - PROSPETTO INDICATIVO PUNTI DI CONSEGNA PROCEDURA APERTA PER L AFFIDAMENTO DELLA FORNITURA DI VACCINO TETRAVALENTE E FARMACI VARI AZIENDA PUNTI DI CONSEGNA ASL DI PRESIDIO OSPEDALIERO DI ARIANO IRPINO, VIA MADDALENA ARIANO AVELLINO IRPINO (AV) PRESIDIO OSPEDALIERO DI SANT ANGELO DEI LOMBARDI, VIA QUADRIVIO S. ANGELO DEI LOMBARDI (AV) PRESIDIO OSPEDALIERO DI BISACCIA, VIA PIANO REGOLATORE, BISACCIA (AV) C/O CEDIFARME VIA MOSCATELLO CANOSA DI PUGLIA (BA) FARM. TERR. C/O P.O LANDOLFI VIA MELITO, SOLOFRA (AV) SERV FARM DS ATRIPALDA- VIA MANFREDI, ATRIPALDA (AV) SERV FARM. DS CERVINARA VIA COSMA, CERVINARA (AV) DS BAIANO PIAZZA NAPOLITANO, BAIANO (AV) DS LAURO VIA MADONNELLE, LAURO (AV) SERV FARM AVELLINO VIA DEGLI IMBIMBO, AVELLINO (AV) DS MONTORO SUPERIORE VIA MUNICIPIO, MONTORO SUP (AV) AREA SAN. BASE MONTEMILETTO - VIA ANNECCHIARICO, MONTEMILETTO (AV) AREA SAN BASE ALTAVILLA IRPINA - VIA SAN FRANCESCO D'ASSISI, MONTEMILETTO (AV) P. S. I . "SAN GIACOMO" VIA LEGNITI, MONTEFORTE IRPINO (AV) DEP DIS DIR C/O SO. CODIN - FARMA MORRA- VIA NAZIONALE TORRETTE, MERCOGLIANO (AV) AREA FARMACEUTICA TERRITORIALE VIA TRIESTE E TRENTO N.4 ASL BN1 82100 BENEVENTO MAGAZZINO 1 SVIMA - C.DA PIANO MORRA - 82100 BENEVENTO MAGAZZINO 2 MANNA VIA GASPARE DEL BUFALO - 82100 BENEVENTO MAGAZZINO FARMACIA P.O. S. M. DELLE GRAZIE CERRETO SANNITA - VIA CESINE DI SOPRA - 82032 CERRETO SANNITA (BN) MAGAZZINO FARMACIA P.O. S. GIOVANNI DI DIO S. AGATA DEI GOTI - VIA CAUDINA 82019 S. AGATA DEI GOTI ( BN ) DISTRETTO SANITARIO ASS. FARMAC. MORCONE - VIA ROMA - 82026 MORCONE ( BN ) DISTRETTO SANITARIO ASS. FARMAC. MONTESARCHIO - VIA IGNAZIO SILONE - 82016 MONTESARCHIO ( BN ) UOPC MONTESARCHIO - VIA NAPOLI - 82016 MONTESARCHIO ( BN ) UOPC DISTRETTO BN 2 - VIA MANZONI - 82018 SAN GIORGIO DEL SANNIO (BN) UOPC TORRECUSO - VIA FABBRICATA - 82030 TORRECUSO ( BN ) UOPC MORCONE - VIA ROMA - 82026 MORCONE ( BN ) UOPC S.AGATA DEI GOTI - VIA STARZA - 82019 S.AGATA DEI GOTI ( BN ) UOPC S. -

Una Rete Castellare: Il Sistema Fortificato Irpino a Network of Castles: the Irpinian Fortified System

Defensive Architecture of the Mediterranean / Vol XII / Navarro Palazón, García-Pulido (eds.) © 2020: UGR ǀ UPV ǀ PAG DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4995/FORTMED2020.2020.11348 Una rete castellare: il sistema fortificato irpino A network of castles: the Irpinian fortified system Giovanni Coppola Università di Napoli “Suor Orsola Benincasa”, Naples, Italy, [email protected] Abstract In Irpinia, to grasp the extent to which the multiform and varied castellated density still has today, it is necessary to look at its hilly and mountainous landscapes or read the toponyms of its villages: from the recent study carried out in the Province of Avellino, there is a list of 78 castles still visible in elevation, a very high figure if you consider that the entire provincial territory is composed of 118 municipalities, for a percentage of almost 70%. The period of study in which this research is based on Irpinia’s fortification (castles, walls, towers and defensive walls) is part of the period in which the various foreign dynasties conquered the Regnum Si- ciliae giving rise to a military architecture which goes from the Longobard domination (568-774) to the advent of the Normans (1130-1194) and the Swabians (1194-1268), to retrace the phases of the coming first of the Angevins (1268-1435) and then of the Aragons (1442-1503). Keywords: castle, fortification, military architecture, medieval architecture, South Italy, Irpinia. L’armatura del sistema difensivo medievale irpino L’Irpinia è una multiforme e variegata “terra di niello, 2012). Durante gli anni successivi alla castelli” che ha risentito enormemente dei desti- caduta dell’Impero romano, il cosiddetto feno- ni dei tanti conquistatori e delle visioni politiche meno dell’incastellamento, dopo che lentamente che ne hanno disegnato i confini e guidato le i centri antichi di fondovalle si spopolavano, ini- sorti. -

COMUNE DI SOLOFRA (AV) 1.1 Settembre 2015 Piano Di Emergenza Comunale Legge N

REL. COMUNE DI SOLOFRA (AV) 1.1 Settembre 2015 Piano di Emergenza Comunale Legge n. 225/1992 e s.m.i. "Istituzione del Servizio Nazionale della Protezione Civile" e D.G.R. Campania n. 146/2013 Relazione del Piano di Emergenza Comunale PARTE I - PARTE GENERALE Piano di Emergenza Comunale (PEC) Legge n. 225 del 1992 e s.m.i. RELAZIONE DEL PIANO DI EMERGENZA COMUNALE Parte I – Parte Generale Piano di Emergenza Comunale (PEC) RELAZIONE Comune di Solofra (AV) PARTE I COMUNE DI SOLOFRA Piazza San Michele, 5 (Palazzo Orsini) – Solofra (AV) Tel. (+39) 0825 582411 – Fax (+39)0825 532494 PEC: [email protected] Il Sindaco Michele VIGNOLA Il Segretario Generale Dott. Antonio ESPOSITO L’Assessore alla Protezione Civile Michele RUSSO Il Responsabile Unico del Procedimento Ingegnere Ennio TARANTINO GRUPPO DI LAVORO Progettisti Geologo Ugo UGATI (Capogruppo mandatario) Architetto Antonio OLIVIERO (Componente mandante) Ingegnere Ferdinando LUMINOSO & Associati (Componente mandante) Agronomo Aniello PALOMBA (Componente mandante) - 2 - Piano di Emergenza Comunale (PEC) RELAZIONE Comune di Solofra (AV) PARTE I Indice PREMESSA ...................................................................................................................................................4 NORMATIVA DI RIFERIMENTO ...................................................................................................................6 1. INQUADRAMENTO TERRITORIALE ................................................................................................9 1.1 POPOLAZIONE -

The Monastery of Montevergine Its Foundation and Early Development

The Monastery of Montevergine Its Foundation and Early Development (1118-1210) Isabella Laura Bolognese Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2013 ~ i ~ The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Isabella Laura Bolognese to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2013 The University of Leeds and Isabella Laura Bolognese ~ ii ~ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS What follows has been made possible by the support and guidance of a great many scholars, colleagues, family, and friends. I must first of all thank my supervisor, Prof. Graham Loud, who has been an endless source of knowledge, suggestions, criticism, and encouragement, of both the gentle and harsher kind when necessary, throughout the preparation and writing of my PhD, and especially for sharing with me a great deal of his own unpublished material on Cava and translations of primary sources. I must thank also the staff and colleagues at the Institute for Medieval Studies and the School of History, particularly those who read, commented, or made suggestions for my thesis: Dr Emilia Jamroziak and Dr William Flynn have both made important contributions to the writing and editing of this work.