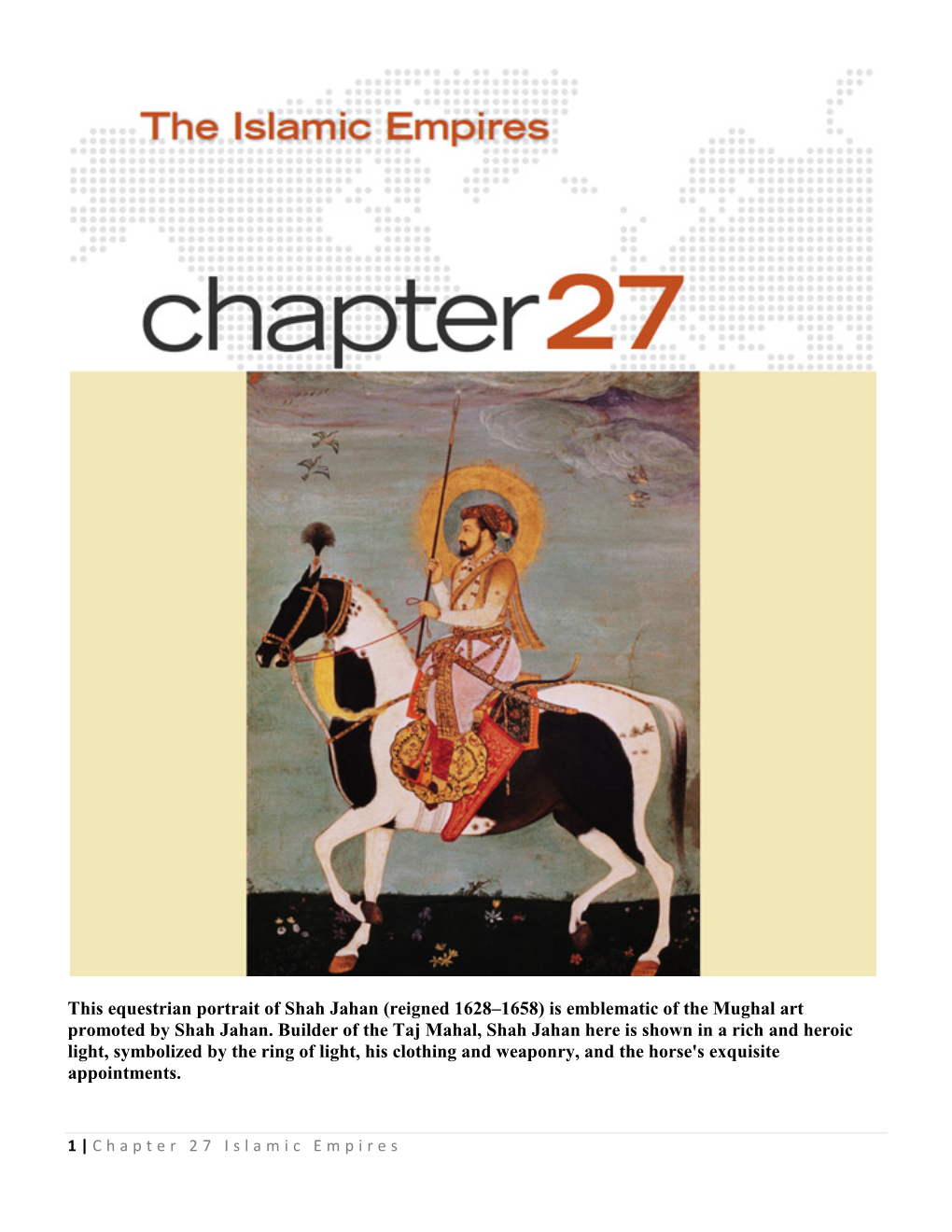

Is Emblematic of the Mughal Art Promoted by Shah Jahan. Builder Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mughal Paintings of Hunt with Their Aristocracy

Arts and Humanities Open Access Journal Research Article Open Access Mughal paintings of hunt with their aristocracy Abstract Volume 3 Issue 1 - 2019 Mughal emperor from Babur to Dara Shikoh there was a long period of animal hunting. Ashraful Kabir The founder of Mughal dynasty emperor Babur (1526-1530) killed one-horned Department of Biology, Saidpur Cantonment Public College, rhinoceros and wild ass. Then Akbar (1556-1605) in his period, he hunted wild ass Nilphamari, Bangladesh and tiger. He trained not less than 1000 Cheetah for other animal hunting especially bovid animals. Emperor Jahangir (1606-1627) killed total 17167 animals in his period. Correspondence: Ashraful Kabir, Department of Biology, He killed 1672 Antelope-Deer-Mountain Goats, 889 Bluebulls, 86 Lions, 64 Rhinos, Saidpur Cantonment Public College, Nilphamari, Bangladesh, 10348 Pigeons, 3473 Crows, and 10 Crocodiles. Shahjahan (1627-1658) who lived 74 Email years and Dara Shikoh (1657-1658) only killed Bluebull and Nur Jahan killed a tiger only. After study, the Mughal paintings there were Butterfly, Fish, Bird, and Mammal. Received: December 30, 2018 | Published: February 22, 2019 Out of 34 animal paintings, birds and mammals were each 16. In Mughal pastime there were some renowned artists who involved with these paintings. Abdus Samad, Mir Sayid Ali, Basawan, Lal, Miskin, Kesu Das, Daswanth, Govardhan, Mushfiq, Kamal, Fazl, Dalchand, Hindu community and some Mughal females all were habituated to draw paintings. In observed animals, 12 were found in hunting section (Rhino, Wild Ass, Tiger, Cheetah, Antelope, Spotted Deer, Mountain Goat, Bluebull, Lion, Pigeon, Crow, Crocodile), 35 in paintings (Butterfly, Fish, Falcon, Pigeon, Crane, Peacock, Fowl, Dodo, Duck, Bustard, Turkey, Parrot, Kingfisher, Finch, Oriole, Hornbill, Partridge, Vulture, Elephant, Lion, Cow, Horse, Squirrel, Jackal, Cheetah, Spotted Deer, Zebra, Buffalo, Bengal Tiger, Camel, Goat, Sheep, Antelope, Rabbit, Oryx) and 6 in aristocracy (Elephant, Horse, Cheetah, Falcon, Peacock, Parrot. -

The Taj: an Architectural Marvel Or an Epitome of Love?

Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 7(9): 367-374, 2013 ISSN 1991-8178 The Taj: An Architectural Marvel or an Epitome of Love? Arshad Islam Head, Department of History & Civilization, International Islamic University Malaysia Abstract: On Saturday 7th July 2007, the New Seven Wonders Foundation, Switzerland, in its new ranking, again declared the Taj Mahal to be one of the Seven Wonders of the World. The Taj Mahal is not just an architectural feat and an icon of luminous splendour, but an epitome of enormous love as well. The Mughal Emperor Shahjahan (1592-1666) built the Taj Mahal, the fabulous mausoleum (rauza), in memory of his beloved queen Mumtaz Mahal (1593-1631). There is perhaps no better and grander monument built in the history of human civilization dedicated to love. The contemporary Mughal sources refer to this marvel as rauza-i-munavvara (‘the illumined tomb’); the Taj Mahal of Agra was originally called Taj Bibi-ka-Rauza. It is believed that the name ‘Taj Mahal’ has been derived from the name of Mumtaz Mahal (‘Crown Palace’). The pristine purity of the white marble, the exquisite ornamentation, use of precious gemstones and its picturesque location all make Taj Mahal a marvel of art. Standing majestically at the southern bank on the River Yamuna, it is synonymous with love and beauty. This paper highlights the architectural design and beauty of the Taj, and Shahjahan’s dedicated love for his beloved wife that led to its construction. Key words: INTRODUCTION It is universally acknowledged that the Taj Mahal is an architectural marvel; no one disputes it position as one of the Seven Wonders of the World, and it is certainly the most fêted example of the considerable feats of Mughal architecture. -

Behind the Veil:An Analytical Study of Political Domination of Mughal Women Dr

11 Behind The Veil:An Analytical study of political Domination of Mughal women Dr. Rukhsana Iftikhar * Abstract In fifteen and sixteen centuries Indian women were usually banished from public or political activity due to the patriarchal structure of Indian society. But it was evident through non government arenas that women managed the state affairs like male sovereigns. This paper explores the construction of bourgeois ideology as an alternate voice with in patriarchy, the inscription of subaltern female body as a metonymic text of conspiracy and treachery. The narratives suggested the complicity between public and private subaltern conduct and inclination – the only difference in the case of harem or Zannaha, being a great degree of oppression and feminine self –censure. The gradual discarding of the veil (in the case of Razia Sultana and Nur Jahan in Middle Ages it was equivalents to a great achievement in harem of Eastern society). Although a little part, a pinch of salt in flour but this political interest of Mughal women indicates the start of destroying the patriarchy imposed distinction of public and private upon which western proto feminism constructed itself. Mughal rule in India had blessed with many brilliant and important aspects that still are shining in the history. They left great personalities that strengthen the history of Hindustan as compare to the histories of other nations. In these great personalities there is a class who indirectly or sometime directly influenced the Mughal politics. This class is related to the Mughal Harem. The ladies of Royalty enjoyed an exalted position in the Mughal court and politics. -

Module 3 Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb Who Was the Successor of Jahangir

Module 3 Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb Who was the successor of Jahangir? Who was the last most power full ruler in the Mughal dynasty? What was the administrative policy of Aurangzeb? The main causes of Downfall of Mughal Empire. Shah Jahan was the successor of Jahangir and became emperor of Delhi in 1627. He followed the policy of his ancestor and campaigns continued in the Deccan under his supervision. The Afghan noble Khan Jahan Lodi rebelled and was defeated. The campaigns were launched against Ahmadnagar, The Bundelas were defeated and Orchha seized. He also launched campaigns to seize Balkh from the Uzbegs was successful and Qandhar was lost to the Safavids. In 1632Ahmadnagar was finally annexed and the Bijapur forces sued for peace. Shah Jahan commissioned the Taj Mahal. The Taj Mahal marks the apex of the Mughal Empire; it symbolizes stability, power and confidence. The building is a mausoleum built by Shah Jahan for his wife Mumtaz and it has come to symbolize the love between two people. Jahan's selection of white marble and the overall concept and design of the mausoleum give the building great power and majesty. Shah Jahan brought together fresh ideas in the creation of the Taj. Many of the skilled craftsmen involved in the construction were drawn from the empire. Many also came from other parts of the Islamic world - calligraphers from Shiraz, finial makers from Samrkand, and stone and flower cutters from Bukhara. By Jahan's period the capital had moved to the Red Fort in Delhi. Shah Jahan had these lines inscribed there: "If there is Paradise on earth, it is here, it is here." Paradise it may have been, but it was a pricey paradise. -

Sher Shah Suri

MODULE-3 FORMATION OF MUGHAL EMPIRE TOPIC- SHER SHAH SURI PRIYANKA.E.K ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY LITTLE FLOWER COLLEGE, GURUVAYOOR Sher Shah Suri, whose original name was Farid was the founder of the Suri dynasty. Son of a petty jagirdar, neglected by his father and ill treated by his step-mother, he very successfully challenged the authority of Mughal emperor Humayun, drove him out of India and occupied the throne of Delhi. All this clearly demonstrates his extra-ordinary qualities of his hand, head and heart. Once again Sher Shah established the Afghan Empire which had been taken over by Babur. The intrigues of his mother compelled the young Farid Khan to leave Sasaram (Bihar), the jagir of his father. He went to Jaunpur for studies. In his studies, he so distinguished himself that the subedar of Jaunpur was greatly impressed. He helped him to become the administrator of his father’s jagir which prospered by his efforts. His step-mother’s jealousy forced him to search for another employment and he took service under Bahar Khan, the ruler of South Bihar, who gave him the title of Sher Khan for his bravery in killing a tiger single-handed. But the intrigues of his enemies compelled him to leave Bihar and join the camp of Babur in 1527. He rendered valuable help to Babur in the campaign against the Afghans in Bihar. In due course, Babur became suspicious of Sher Khan who soon slipped away. As his former master Bahar Khan, the ruler of South Bihar had died, he was made the guardian and regent of the minor son of the deceased. -

Mumtaz Mahal - the Inspiration

Mumtaz Mahal - The Inspiration Taj Mahal – a symbol of true love built in the memory of beautiful Mumtaz Mahal or Arjumand Banu, still stands as the supreme unparalleled grand monument ever built in the history of human civilization. Arjumand Banu was the daughter of Asaf Khan, who was married to Shahjahan at an early age of 14 years. Imperial city of Agra was already agog with stories of her charm and beauty. She was the third wife of Shahjahan (Prince Khurram) and the most favourite one throughout his life. She was named Mumtaz Mahal in 1612 after her marriage and remained as an inseparable companion of her husband till death. As a symbol of her faith and love, she bore Shahjahan 14 children and died during the birth of their last child. For the love and affection she showed to her husband, Mumtaz Mahal received highest honour of the land – with Royal seal – ‘Mehr Uzaz’ from the Emperor - Shahjahan. The emperor and his empress moved towards Maharashtra or Deccan in the year 1630 to supress Lodi Empire that was gaining strength at that time. This was the last journey that Mumtaz Mahal ever took. She breathed her last after delivering their 14th child (a daughter) in the city of Burhanpur in June 17, 1631. It is said that Mumtaz Mahal on her deathbed asked Shahjahan to create a symbol of their Love for its posterity, and her loyal husband accepted it immediately. Though, many historians do not agree with this story, saying that it was the grief-stricken emperor himself who decided to build the most memorable symbol of love in the world. -

DECLINE of the Mughal Empire

Class: 8 A,B &C HISTORY 17th July 2020 Chapter 5 DECLINE OF THE Mughal Empire The transition from the Medieval to the Modern Period began with the decline of the Mughal Empire in the first half of the 18th Century. This was followed by the East India Company’s territorial conquests and the beginning of the political domination of India in the middle of 18th Century. The Modern Period in India is generally regarded as having begun in the mid- 18th century. During the first half of the 18th Century the great Mughal Empire decayed and disintegrated. The Mughal Emperors lost their power and glory and their vast empire finally shrank to a few square miles around Delhi. The unity and stability had already been shaken during Aurangzeb’s long reign of about 50 years. The death of Aurangzeb, the last of the great Mughals, was followed by a war of succession among his three sons. Bahadur Shah eventually ascended the throne in 1707 at the age of 65. He became the first in a line of emperors referred to as the Later Mughals. THE LIST OF THE LATER MUGHALS (1707- 1857) 1) Bahadur Shah (1707-12) 2) Jahandar Shah (1712-13) 3) Farrukhshiyar ( 1713-19) 4) Muhammad Shah (1719-48) 5) Ahmad Shah (1748-54) 6) Alamgir II (1754-59) 7) Shah Alam II (1759-1806) 8) Akbar II ( 1806-37) 9) Bahadur Shah Zafar (1737_1857) THE REASONS FOR THE DECLINE OF THE MUGHAL EMPIRE 1) Politics in the Mughal Court; 2) Jagirdari Crisis; 3) Weak Military organization and Administration; 4) Wars of succession; 5) Aurangzeb’s policies; 6) Economic bankruptcy 7) Foreign invasions 8) Weak successors. -

Module-3 Formation of Mughal Empire Topic-Akbar

MODULE-3 FORMATION OF MUGHAL EMPIRE TOPIC-AKBAR PRIYANKA.E.K ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY LITTLE FLOWER COLLEGE, GURUVAYOOR Jalal-Ud-din Mohammad Akbar, son of Humayun was born at Amarkot (in Sind) on 15 October, 1542 in the house of a Rajput chief. Akbar spent his childhood under conditions of adversity and un-certainty as Humayun was in exile. Arrangements for his formal education were made by Humayun after his restoration to the throne of Kabul but Akbar was more interested in sports and martial exercises than in studies. In 1551 Akbar was made the governor of Ghazni and he remained its governor till November 1554 when Humayun embarked on an expedition for the conquest of Hindustan. Akbar was given nominal command of the army of Indian invasion and was given the credit of Humayun’s victory at Sirhind in January 1555. After his occupation of Delhi Humayun, declared Akbar to be the heir apparent and assigned to him the Governorship of the Punjab. Humayun died in January 1556 as a result of the fall from the staircase of his library. At that time Akbar was just a boy of 14. When the news of his father’s death reached, Akbar was at Kalanaur 15 miles west of Gurdaspur in Punjab. His guardian Bairam khan took immediate steps to enthrone him on brick-platform and performed the ceremony thereby proclaiming him the emperor on February 14, 1556 Challenges before Akbar Though Humayun had recovered Delhi in June 1555 he had not been able to consolidate his position in India therefore everything was in a chaos. -

Women at the Mughal Court Perception & Reality

Women at the Mughal Court Perception & Reality What assumptions or questions do you have about the women depicted in the following nine paintings? What was life like in the zenana or women’s quarters? How much freedom did they have? With our new online catalogue we are drawing attention to this under-explored area. We look at the fascinating lives and achievements of these women, and how they have been represented, or misrepresented. Women at the Mughal Court Perception & Reality When we look at cat. 1, ‘A Princess is attended by her Women’, one can imagine how such an image could be misinterpreted. For centuries, the women of the Mughal court and the space of the zenana (the women’s quarters of a household) in particular have often been neglected by art historians and represented by European visitors and later writers and artists in Orientalist terms. This is the idea of the ‘exotic’ harem as a place of purely sensuous languor, where thousands of nubile young women are imprisoned and lead restricted lives as sex objects, full of jealousy and frustration. As we might expect, the truth is far more complex, rich, and surprising. Certainly, as the wonderful details of cat. 1 attest, the highest-ranking women of this society enjoyed an extremely sophisticated luxury and beauty culture. Our princess’ every need is being attended to: women on the left bring her fruit and a covered cup with a drink; one woman shampoos her feet to cool them while others hold a peacock, a morchhal, attend the incense burner, and sing and play on the tambura as musical accompaniment. -

City Overview

Agra, India April 2018 City Overview Welcome to the amazing tourism city of the Taj Mahal - Agra, India. The seat of the great Mughal rulers for ages Agra, India offers its treasure trove for all the tourists from India and abroad. Even though Agra, India is synonymous with the Taj, the city stands in testimony to the great amount of architectural activity of the Mughals. TajMahal is the epitome of love, poem in white marble, one of the Seven Wonders of the World besides being the pride of India. In fact all the monuments of Agra, India have contributed to Agra Tourism. Terrific Agra Packages from us will ensure you plan your Agra Travel soon. Delhi to Agra to Jaipur make the famous Golden Triangle tour of India. 2 Your Trip: Your travel just pulled into the romantic city of Agra. Check out some of the things you saw while you were riding the train into the city. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fMpV94vzSHA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P5aw8DzYUa0 The first thing you want to do once you get to this amazing city is go check out the Taj Mahal! Make sure to spend plenty of time at this incredible building. Taj Mahal, "the epitome of love", is "a monument of immeasurable beauty". https://www.airpano.ru/files/Taj-Mahal-India/2-2 Taj Mahal The Taj Mahal of Agra is one of the Seven Wonders of the World, for reasons more than just looking magnificent. It's the history of Taj Mahal that adds a soul to its magnificence: a soul that is filled with love, loss, remorse, and love again. -

June 2019 Question Paper 01 (PDF, 3MB)

Cambridge Assessment International Education Cambridge Ordinary Level BANGLADESH STUDIES 7094/01 Paper 1 History and Culture of Bangladesh May/June 2019 1 hour 30 minutes Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper *0690022029* READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST An answer booklet is provided inside this question paper. You should follow the instructions on the front cover of the answer booklet. If you need additional answer paper ask the invigilator for a continuation booklet. Answer three questions. Answer Question 1 and two other questions. You are advised to spend about 30 minutes on each question. The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part question. This document consists of 9 printed pages and 3 blank pages. 06_7094_01_2019_1.2 © UCLES 2019 [Turn over 2 You must answer all parts of Question 1. 1 The Culture and Heritage of Bangladesh You are advised to spend about 30 minutes on this question. (a) This question tests your knowledge. (i) Alaol was able to find work in the royal court of Arakan because: A he was well known as a poet B his father was well known by the court of Arakan C he was introduced to the people there by pirates D he had won a literary award [1] (ii) Scholars criticised Rabindranath Tagore because: A he wrote under a pen name B he did not focus on one subject C his poems were simple D he used colloquial language in his writing [1] (iii) Which of the following was not among Kazi Nazrul Islam’s accomplishments? A recording songs B painting pictures C creating stories D writing poems [1] (iv) Which of the following was written by Jasimuddin while he was a student? A Kabar (The Grave) B Rakhali (Shepherd) C Nakshi Kanthar Math D Bagalir Hashir Golpo [1] (v) Zainul Abedin’s paintings are known because of his use of which of the following characteristics? A Pastel colours B Circles C The black line D Symmetry [1] © UCLES 2019 06_7094_01_2019_1.2 3 (b) This question tests your knowledge and understanding. -

The Great Mughal Empire (1526-1707)

THE GREAT MUGHAL EMPIRE (152 6-1707) THE GREAT MUGHAL EMPERORS EMPEROR REIGN START REIGN END BABUR 1526 1530 HUMAYUN 1530 1556 AKBAR 1556 1605 JAHANGIR 1605 1627 SHAH JAHAN 1627 1658 AURANGZEB 1658 1707 BABUR Birth name:Zāhir ud-Dīn Maham Begum Mohammad Masumeh Begum Family name:Timurid Nargul Agacheh Title:Emperor of Mughal Sayyida Afaq Empire Zainab Sultan Begum Birth:February 14, 1483 Death:December 26, 1530 Children: Succeeded by:Humayun Humayun, son Marriage: Kamran Mirza, son Ayisheh Sultan Begum Askari Mirza, son Bibi Mubarika Yusufzay Hindal Mirza, son Dildar Begum Gulbadan Begum, daughter Gulnar Agacheh Fakhr-un-nisa, daughter Gulrukh Begum HUMANYUN Birth name: Nasiruddin Children: Akbar, son Humayun Muhammad Hakim, son Family name: Timurid Title: Emperor of Mughal Empire Birth: March 6, 1508 Place of birth: Kabul, Afghanistan Death: February 22, 1556 Succeeded by: Akbar Marriage: Hamida Banu Begum AKBAR Birth name: Jalaluddin Ruqayya Sultan Begum Muhammad Akbar Sakina Banu Begum Family name: Timurid Salima Sultan Begum Title: Emperor of Mughal Empire Children: Jahangir, son Shah Murad, son Birth: October 15, 1542 Danyal, son Place of birth: Umarkot, Shahzada Khanim, Sindh daughter Death: October 27, 1605 Shakarunnisa Begum, Succeeded by: Jahangir daughter Marriage: Jodhabai (?) or Aram Banu Begum, Jodhi Bibi daughter Mariam-uz-Zamani Ximini Begum, daughter JAHANGIR Birth name: Nuruddin Children: Nisar Begum, Jahangir daughter Family name: Timurid Khurasw, son Title: Emperor