24/7 Normalized Water Supply Through Innovative Public-Private

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ಕ ೋವಿಡ್ ಲಸಿಕಾಕರಣ ಕ ೋೇಂದ್ರಗಳು (COVID VACCINATION CENTRES) Sl No District CVC Na

ಕ ೋ풿蓍 ಲಕಾಕರಣ ಕ ೋᲂ飍ರಗಳು (COVID VACCINATION CENTRES) Sl No District CVC Name Category 1 Bagalkot SC Karadi Government 2 Bagalkot SC TUMBA Government 3 Bagalkot Kandagal PHC Government 4 Bagalkot SC KADIVALA Government 5 Bagalkot SC JANKANUR Government 6 Bagalkot SC IDDALAGI Government 7 Bagalkot PHC SUTAGUNDAR COVAXIN Government 8 Bagalkot Togunasi PHC Government 9 Bagalkot Galagali Phc Government 10 Bagalkot Dept.of Respiratory Medicine 1 Private 11 Bagalkot PHC BENNUR COVAXIN Government 12 Bagalkot Kakanur PHC Government 13 Bagalkot PHC Halagali Government 14 Bagalkot SC Jagadal Government 15 Bagalkot SC LAYADAGUNDI Government 16 Bagalkot Phc Belagali Government 17 Bagalkot SC GANJIHALA Government 18 Bagalkot Taluk Hospital Bilagi Government 19 Bagalkot PHC Linganur Government 20 Bagalkot TOGUNSHI PHC COVAXIN Government 21 Bagalkot SC KANDAGAL-B Government 22 Bagalkot PHC GALAGALI COVAXIN Government 23 Bagalkot PHC KUNDARGI COVAXIN Government 24 Bagalkot SC Hunnur Government 25 Bagalkot Dhannur PHC Covaxin Government 26 Bagalkot BELUR PHC COVAXINE Government 27 Bagalkot Guledgudd CHC Covaxin Government 28 Bagalkot SC Chikkapadasalagi Government 29 Bagalkot SC BALAKUNDI Government 30 Bagalkot Nagur PHC Government 31 Bagalkot PHC Malali Government 32 Bagalkot SC HALINGALI Government 33 Bagalkot PHC RAMPUR COVAXIN Government 34 Bagalkot PHC Terdal Covaxin Government 35 Bagalkot Chittaragi PHC Government 36 Bagalkot SC HAVARAGI Government 37 Bagalkot Karadi PHC Covaxin Government 38 Bagalkot SC SUTAGUNDAR Government 39 Bagalkot Ilkal GH Government -

O Rigin Al a Rticle

International Journal of Textile and Fashion Technology (IJTFT) ISSN (P): 2250-2378; ISSN (E): 2319-4510 Vol. 9, Issue 4, Aug 2019, 1-10 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. AN IMPACT OF WOVEN KASUTI NEGI MOTIFS IN ILKAL SAREES USING REGENERATED CELLULOSE YARNS JYOTHI KORDHANYAMATH 1 & Dr. S. KAUVERYBAI 2 1Assistant Professor, Acharya Institute of Graduate Studies, Bangalore, India 2Associate Professor, Smt V H D Central Institute of Home Science Bangalore, India ABSTRACT India has a diverse and rich textile tradition which is known for its beauty and ethnicity. The textiles are highly appreciated all over the world and considered as prestigious possession by everyone. Ilkal is one of the traditional textiles which is famous all over the world. Topeteniseragu and kondi techniques are the unique factors of Ilkal saree. The strength and magnificence of the Ilkal sarees makes it one of the favourites among women. The present study aims at revival of traditional IIkal sarees with two concepts. First one is to weave a kasutinegi motif in Ilkalsaree and second one is to introduce regenerated cellulose yarns in weaving Ilkalsaree. The kasuti motifs are being woven into Ilkal sarees with jacquard setup using extra set of weft yarns. Original Article Article Original KEYWORDS: Ilkal, Topeteni, Kondi Technique, Negi Motif & Regenerated Cellulose Yarns Received: May 14, 2019; Accepted: Jun 04, 2019; Published: Jun 24, 2019; Paper Id.: IJTFTAUG20191 INTRODUCTION India is a country with diversified customs and cultures. Ilkal is famous by the name of Ilkal town in Karnataka. It is nearer to the borders of two states Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. -

Groundwater Quality Analysis of Hungundtaluk with Emphasis on Fluoride

IJRET: International Journal of Research in Engineering and Technology eISSN: 2319-1163 | pISSN: 2321-7308 GROUNDWATER QUALITY ANALYSIS OF HUNGUNDTALUK WITH EMPHASIS ON FLUORIDE AnuradhaTanksali1, Veena S Soraganvi2 1Research Scholar Department of Civil Engineering Basaveshawr Engineering College, Bagalkot and Asst. Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, BLDEA college of Engineering, Bijapur; 2Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, Basaveshwar Engineering College Abstract The uncertainty associated with the availability of surface water both in terms of quantity and quality made people to depend on ground water. But in recent years, depletion of water table and mineral contamination like Fluoride are the causes of concern. Some previous studies show people affected with symptoms of Fluoride contamination in Hungund area. Hence to analyze the fluoride content and other co-relating parameters we selected some bore wells in Amingad and Kamatgi of Hungundtaluk, Bagalkot district of Karnataka. Our study mainly comprises of determining the mineral parameters present in groundwater with emphasis on fluoride. The water samples from the bore wells of above two places are collected and parameters like Total Hardness, Fluoride, Alkalinity, Acidity, pH, Conductivity, Chloride and Sulphates are analyzed in the laboratory. The obtained fluoride concentration is correlated with other parameters.Along with the parameters, the geological strata surrounding the selected bore well is identified and correlated with fluoride concentration. The fluoride concentration is high (1.58 –11.6 mg/L) in 18 out of 29 groundwater samples analysed. The regression equations were developed by taking Fluoride as dependent variable and other water quality parameters as independent variables. Compared to other parameters total hardness and chloride indicate stronger relation Keywords: Fluoride, Fluorosis, pH, dissociation of fluoride, geological strata. -

Karnataka Map Download Pdf

Karnataka map download pdf Continue KARNATAKA STATE MAP Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to make this map image accurate. However, GISMAP IN and its owners are not responsible for the correctness or authenticity of the same thing. The GIS base card is available for all areas of CARNATAKA. Our base includes layers of administrative boundaries such as state borders, district boundaries, Tehsil/Taluka/block borders, road network, major land markers, places of major cities and towns, Places of large villages, Places of district headquarters, places of seaports, railway lines, water lines, etc. and other GIS layers, etc. map data can be provided in a variety of GIS formats, such as shapefile or Tab, etc. MAP DATA LAYERS DOWNLOAD You can download freely available map data for Maharashtra status in different layers and GIS formats. DOWNLOAD A MAP OF KARNATAKA COUNTY BROSWE FOR THE KARNATAKA DISTRICTS VIEW THE KARNATAKA BAGALKOT AREA CHICKMAGAL, HASSAN RAMANAGAR BANGALORE CHIKKABALLAPUR SHIMAFI CHIMOGA BANGALORE RURAL CHITRADURGA CODAGAU TUMKUR BELGAUM DAKSHINA KANNADA KAMAR UDUPI BELLARY DAVANGERE KOPPAL UTTARA KANNADA BIDAR DHARWAD MANDYA YADGIR BIJAPUR (KAR) GADAG MYSORE CHAMRAJNAGAR GULBARGA RAICHUR BROSWE FOR OTHER STATE OF INDIA Karnataka Map-Karnataka State is located in the southwestern region of India. It borders the state of Maharashtra in the north, Telangana in the northeast, Andhra Pradesh in the east, Tamil Nadu in the southeast, Kerala in the south, the Arabian Sea to the west, and Goa in the northwest. Karnataka has a total area of 191,967 square kilometres, representing 5.83 per cent of India's total land area. -

Maps of Bagalkot District

MAPS OF BAGALKOT DISTRICT Page 1 Important officials and their contact numbers 1 State Level Officers Officers Phone numbers Name Office Residence Mobile Chief Secretary Dr E V Ramanareddy 080-22252442 080-22256569 Chief Electoral Officer Sanjeev Kumar 080-22242042 080-23514959 9448290830 Regional Commissioner P A Meghannavar 0831-2404007 0831-2422721 9448453999 I G (Belgaum Range) 0831-2405200 0831-2405201 9480800029 2. Important Officials in the CEO’s Office Sl No Name and Designation of Activities to be monitored Contact Number State Nodal Officers 1 Sri K. G. Jagadeesha Implementation of MCC Ph: 080-22288821 Additional CEO-I Mainaintance of Law & Order Election Expenditure Monitoring Expenditure Obeservers (Protocol) 2 Sri Ujjwal Kumar Ghosh Manpower Management and Data Ph: 080-22242024 Additional CEO-II Computerization Transport Management Counting Halls & Strong Rooms Welfare of Polling Personnel 3 Sri. Raghavendra EVMs & VVPATs Management Ph: 080-22224195 Deputy CEO 4 Sri. Surya Sen IT & use of Technology EMS Ph: 080-22288822 Joint CEO Monitoring & Communication plan Website 5 Sri. H. Jnanesh Training Management Ph: 080-22288824 DCEO-III 6 Sri K. N. Ramesh Materials Management Ph: 080-22234198 Joint CEO Ballot Papers, Dummy Ballot Paper & Postal Ballot Papers General Observers Protocol Polling Stations, Provision for PWDs 7 Sri D. N. Naik Helpline & Complaints redressal Ph: 080-22288823 Sr. Consultant 8 Sri. B. S. Hiremath Media/ Political Parties Communication Ph: 7259900300 Sr. Consultant Conduct of meetings & Drawing Proceedings. Documentation/ Monitoring 9 Sri Vastrad. P. S SVEEP action plan Developing of content for SVEEP Documentation of SVEEP Page 2 3. General Observers Name Constituency Mobile Liaison Officer Mobile 19. -

SOLUTIONS to MITIGATE FLUOROSIS in HUNGUD DISTRICT of KARNATAKA- INDIA Chandrasekharam, D., Jalihal A.A., Hema, C.T

SOLUTIONS TO MITIGATE FLUOROSIS IN HUNGUD DISTRICT OF KARNATAKA- INDIA Chandrasekharam, D., Jalihal A.A., Hema, C.T. Department of Earth Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, 400076, India. ABSTRACT World Bank estimated that around 260 million people worldwide in 30 countries have been drinking water with > 1 ppm of fluoride. India is one among such countries where 1 million people are affected by endemic fluorosis. This is particularly so in the state of Karnataka where 6 districts, comprising 4.6% of the geographical area is affected with this problem. We report here the problem of fluorosis in Hungud district of Karnataka, a drought prone area, where previous investigation has not been carried out. Fluoride concentration in the groundwater varies from 0.1 to 7.6 ppm, which is well above the limit of 1.5ppm prescribed by the WHO. Groundwater occurring in gneisses has the maximum concentration of fluoride (7.6ppm) and is saturated with fluorite. Granites, Gneiss and schist are the main hard rock aquifers, which contain fluorine-bearing minerals such as fluorite (5% modal) and biotite with 2% of F. Besides natural sources, granite industry is enhancing F in groundwater. The best solution to mitigate this problem is inter-basin transfer of water from the Western Ghats catchment area into the Krishna River basin. Inter-basin transfer of water will reduce the incidence of F in groundwater in other affected regions of the country also. This is possible if only water becomes a “Centre” rather than a “State subject”. 1 INTRODUCTION In India endemic fluorosis has affected over one million people (Teotia et al, 1981). -

The Deccan Odyssey JOURNEY

TRAIN : The Deccan Odyssey JOURNEY : Jewels of the Deccan Journey Journey Duration : Upto 8 Days Day to Day Itinerary Day 01: Mumbai Early evening, guests are expected to assemble at Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus at 1530 hours, and complete their registration and check-in formalities. Enjoy the royal and traditional Indian welcome by the staff followed by a refreshing drink. Later, you are taken to your respective cabins. Settle and relax as the Deccan Odyssey as the train leaves for Bijapur in Karnataka. Dinner and overnight stay. Day 02: Bijapur Today morning enjoy your breakfast, as the luxury train rolls into Bijapur. Established by Kalyani Chalukyas between 10th and 11th centuries, Bijapur is a popular city in Karnataka. It is the historic capital of Sultans of Deccan. When Bijapur was under the support of Adil Shah dynasty, the city was one among the renowned cities of the country surpassing great cities like that of Agra and Delhi. In fact, with the generous support of Adil Shahi Sultans, Bijapur was majorly flocked by scholars, poets, painters, dancers, calligraphers, musicians and Sufi saints. Later, the place was also titled as the 'Palmyra of the Deccan'. Begin your trip with a visit to the first attraction, Gol Gumbaz; the second largest tomb in the world and mausoleum of Adil Shah, the Sultan of Bijapur. As the name suggests, the Gol Gumbaz is a round dome, the structure of the dome celebrates the success of Deccan architecture. The dome constitutes of a circular gallery, which has an amazing aspect of echoing, every little murmur. Later, you proceed ahead to Jumma Masjid (one of the first mosques of India), Malik-e-Maidan (the largest medieval canon in the world), Mehtar Mahal (it is a 17th century ornamental entrance to a mosque), Ibrahim Rouza (one of the Islamic monuments comprising of a 24 m high minarets). -

North Karnataka Urban Sector Investment Program Tranche 4 – Ilkal Roads

Draft Initial Environmental Examination August 2013 IND: North Karnataka Urban Sector Investment Program Tranche 4 – Ilkal Roads Prepared by Karnataka Urban Infrastructure Development and Finance Corporation, Government of Karnataka for the Asian Development Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 01 July 2013) Currency unit – rupee (INR) INR1.00 = $.0167943034 $1.00 = INR 59.544 Abbreviations ADB - Asian Development Bank CC - cement concrete CFE - consent for establishment CFO - consent for operation CMC - city municipal council CPCB - Central Pollution Control Board CSS - consultant supervision specialist DSC - design and supervision consultants EA - executing agency EIA - environmental impact assessment EMP - environmental management plan ES - environment specialist GRC - grievance redress committee GRM - grievance redress mechanism HDPE - high density polyethylene IA - implementing agency IEE - initial environmental examination km - kilometers KSPCB - Karnataka State Pollution Control Board KUIDFC - Karnataka Urban Infrastructure Development and Finance Corporation lpcd - liter per capita per day m - meters MFF - multi-tranche financing facility MLD - million liters per day mm - millimeters MoEF - Ministry of Environment and Forest NGO - non-government organization NKUSIP - North Karnataka Urban Sector Improvement Program PIU - project implementation unit PMU - project management unit PVC - polyvinyl chloride RCC - reinforced cement concrete ROW - right of way SEIAA - State Environmental Impact Assessment Authority SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement STP - sewage treatment plant ULB - urban local body WTP - water treatment plant 3 NOTES In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. and ―INR‖ refers to Indian rupees This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

Bagalkote District, Karnataka State

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET BAGALKOTE DISTRICT, KARNATAKA STATE SOUTH WESTERN REGION BANGALORE APRIL 2011 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET BAGALKOTE DISTRICT, KARNATAKA STATE SOUTH WESTERN REGION BANGALORE APRIL 2011 B BAGALKOTE DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl.No Items Statistics 1 GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical area (Sq km) 6595.0 ii) Administrative Divisions (As on 31/3/2006) Number of Taluks 6 Numbers of Villages 623 iii) Population (As on 2001 census) 16,51,892 iv) Average Annual rainfall (mm) 579 mm (Av. 10 years: 1996-2005) 2 GEOMORPHOLOGY i) Major physiographic units Undulating plains interspersed with sporadic dissected hills to rugged topography. ii) Major Drainages Krishna main basin: Malaprabha & Ghataprabha sub-basins. 3 LAND USE (Sq.km) i) Forest area: 811.26 ii) Net area sown: 4697.83 iii) Cultivable area: 4754.59 4 MAJOR SOIL TYPES Red sandy soil, red loamy soil & black cotton soil 6 IRRIGATION BY DIFFERANT SOURCES (Area in Ha & Numbers of Structures) Dugwells 27030 Tube wells/Borewells 56865 Tanks/Ponds 677 Canals 50630 I Sl.No Items Statistics Others sources (including Lift irrigation) 77670 Net Irrigated Area 212872 Gross Irrigated Area - 7 NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB (as on 31-3- 2007) No of Dug wells 28 No of Piezometers 10 8 PREDOMINENT GEOLOGICAL FORMATIONS Sandstone, Quartzite, Limestone, Shales, Basalt, Schist, Granite and Gneiss. 9 HYDROGEOLOGY Major water bearing formation Weathered & fractured sandstones, shales, limestones, basalts, gneisses, granites and schists. (Pre-monsoon Depth to water level during 2010) Min. -

Bedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA

pincode officename districtname statename 560001 Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 HighCourt S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Legislators Home S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Mahatma Gandhi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Rajbhavan S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vidhana Soudha S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 CMM Court Complex S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vasanthanagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Bangalore G.P.O. Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore Corporation Building S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore City S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Malleswaram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Palace Guttahalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Swimming Pool Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Vyalikaval Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Gavipuram Extension S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Mavalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Pampamahakavi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Basavanagudi H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Thyagarajnagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560005 Fraser Town S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 Training Command IAF S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 J.C.Nagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Air Force Hospital S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Agram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 Hulsur Bazaar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 H.A.L II Stage H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 Bangalore Dist Offices Bldg S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 K. G. Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Industrial Estate S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar IVth Block S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA -

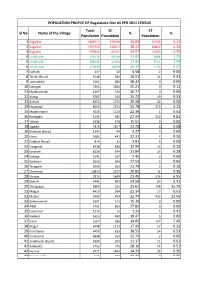

Sl No Name of the Village Total Population SC Population % ST

POPULATION PROFILE OF Bagalakote Dist AS PER 2011 CENSUS Total SC ST Sl No Name of the Village % % Population Population Population 1 Bagalkot 1889752 319149 16.89 97203 5.14 2 Bagalkot 1291906 238014 18.42 80820 6.26 3 Bagalkot 597846 81135 13.57 16383 2.74 4 Jamkhandi 470176 80138 17.04 5866 1.25 5 Jamkhandi 298146 52059 17.46 4711 1.58 6 Jamkhandi 172030 28079 16.32 1155 0.67 7 Kalhatti 437 20 4.58 0 0.00 8 Terdal (Rural) 5548 583 10.51 24 0.43 9 Tamadaddi 3101 882 28.44 0 0.00 10 Halingali 7363 1856 25.21 9 0.12 11 Madanamatti 1207 130 10.77 0 0.00 12 Asangi 5787 910 15.72 19 0.33 13 Kulhalli 8353 1702 20.38 42 0.50 14 Hipparagi 8560 1351 15.78 270 3.15 15 Madarkhandi 5026 1124 22.36 1 0.02 16 Bandigani 2140 585 27.34 210 9.81 17 Yallatti 3338 518 15.52 0 0.00 18 Jagadal 7815 1817 23.25 6 0.08 19 Banhatti (Rural) 1345 44 3.27 0 0.00 20 Hosur 3582 441 12.31 7 0.20 21 Rabkavi (Rural) 814 31 3.81 0 0.00 22 Hangandi 6438 836 12.99 13 0.20 23 Sasalatti 8226 974 11.84 23 0.28 24 Kaltippi 2241 167 7.45 0 0.00 25 Golbhavi 5099 894 17.53 3 0.06 26 Yaragatti 3005 652 21.70 3 0.10 27 Chimmad 10839 2257 20.82 32 0.30 28 Navalgi 7875 1689 21.45 516 6.55 29 Kalhalli 3441 843 24.50 83 2.41 30 Shiraguppi 3809 595 15.62 598 15.70 31 Maigur 4419 934 21.14 27 0.61 32 Muttur 3589 459 12.79 415 11.56 33 Kankanawadi 3391 515 15.19 0 0.00 34 Albal 2491 693 27.82 0 0.00 35 Hanchinal 1214 15 1.24 5 0.41 36 Kadakol 2653 490 18.47 0 0.00 37 Sanal 2107 296 14.05 157 7.45 38 Alagur 6448 1123 17.42 17 0.26 39 Kunchanur 4490 833 18.55 24 0.53 40 Kumbarhal 4848 -

Bagalkote Site of Heritage and Religion Overview

Bagalkote Site of heritage and religion Overview Bagalkote town is 90 kms away from the city of Vijayapura. According to a legend, the town was believed to be granted to the Vajantries (ie. Village orchestra) of Ravana. The district has worldwide renowned historical destinations including temples of Pattadakal, Mahakuteshwar, Shivayogmandir and Banashankari temple. The place illustrates vivacious colours and can be portrayed as the city of ancient Indian temples District 6,552 Area Introduction Bagalkote Headquarter sq. kilometre ► Located in the northern part of Karnataka 15º49’ & 16º46’ N ► New district carved out of Bijapur District in 1997 latitude Average 584 Location 74º59’ & 76º20’ E Rainfall millimetres ► Divided into 6 Administrative Divisions: Badami, longitude Bilagi, Bagalkot, Hunagund, Jamakhandi and Mudhol o 38 C Krishna, maximum Temperature Rivers Malaprabha and ► Ruled upon by dynasties such as Adilshahi o 18 C Ghataprabha Empire, Nawabs of Savanura, Marathas and minimum rulers such as Haidar Ali Population 989 ► Location of several UNESCO heritage sites 288 Density Sex Ratio females per 1,000 persons per sq.km males ► Rich in Limestone, Pink Granite, Copper, Iron ore, Dolomite Population 75.77 (as per Census Literacy Rate ► 18.89 lakhs percent Popular for its silk and handloom industries and 2011) famous Ilkal sarees Page 2 District Profile : Bagalkote Economy ► GDDP is INR 24,311 Crore in the year 2014 -15 (at Bagalkote District’s Contribution to GDDP of Karnataka (2014- Current Prices) 15)- at current prices ► 32% urbanisation in the district as compared to 39% in Description INR Crores Contribution the state (%) ► Bagalkote is primarily an agrarian economy with over Total District GDP 24,311 2.6 70% of the net area under cultivation.