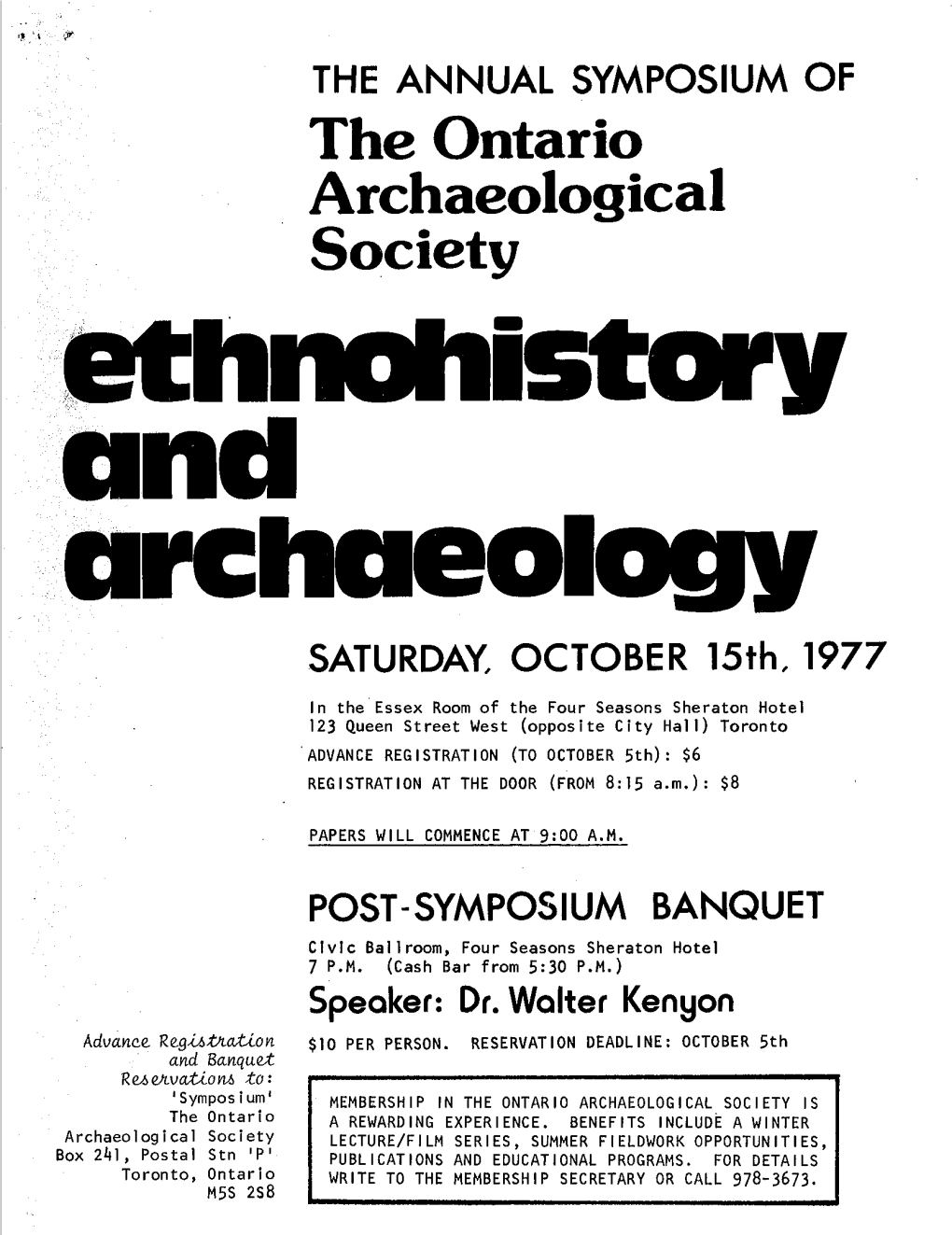

6 REGISTRATION at the DOOR (FROM 8:15 A.M.): $8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER/BULLETIN the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada La Societe Royale D’Astronomie Du Canada Supplement to the Journal Vol

NEWSLETTER/BULLETIN The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada La Societe Royale d’Astronomie du Canada Supplement to the Journal Vol. 84/2 Supplément au Journal Vol. 84/2 Vol. 2/2 April/avril 1990 1990 General Assembly Ottawa, Canada C O M E H E L P U S C E L E B R A T E T H E S O C I E T Y ’ S C E N T E N N I A L ! 18 N E W S L E T T E R / B U L L E T I N The Newsletter/Bulletin is a publication of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and is distributed together with the Society’s Journal. Inquiries about the Society should be directed to the National Office at 136 Dupont Street, Toronto, Ontario M5R 1V2. Editor: IAN G. McGREGOR Editorial Staff: HARLAN CREIGHTON, DAVID LEVY, STEVEN SPINNEY Rédacteur pour les Centres français: MARC A. GÉLINAS 11 Pierre-Ricard, N-D-Ile-Perrôt, Québec J7V 5V6 University of Toronto Press Liaison: AL WEIR Mailing Address: McLaughlin Planetarium, 100 Queen’s Park, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2C6 FAX Number: (416) 586-5863 Deadline for August issue is May 1. Night Skies in Cyprus Hills Provincial Park by Don Friesen Saskatoon Centre Cyprus Hills Provincial Park is located in the extreme south-western corner of Saskatchewan. Its elevation ranges from 1000 to 1200 metres above sea level. Large ranches which surround Cyprus Hills have left them virtually undisturbed for thousands of years. One evening last January I drove from Saskatoon to Maple Creek, a town just beside Cyprus to visit my sister and view the skies. -

Sphere, Sweet Sphere: Recycling to Make a New Planetarium Page 83

Online PDF: ISSN 23333-9063 Vol. 45, No. 3 September 2016 Journal of the International Planetarium Society Sphere, sweet sphere: Recycling to make a new planetarium Page 83 Domecasting_Ad_Q3.indd 1 7/20/2016 3:42:33 PM Executive Editor Sharon Shanks 484 Canterbury Ln Boardman, Ohio 44512 USA +1 330-783-9341 [email protected] September 2016 Webmaster Alan Gould Lawrence Hall of Science Planetarium Vol. 45 No. 3 University of California Berkeley CA 94720-5200 USA Articles [email protected] IPS Special Section Advertising Coordinator 8 Meet your candidates for office Dale Smith (See Publications Committee on page 3) 12 Honoring and recognizing the good works of Membership our members Manos Kitsonas Individual: $65 one year; $100 two years 14 Two new ways to get involved Institutional: $250 first year; $125 annual renewal Susan Reynolds Button Library Subscriptions: $50 one year; $90 two years All amounts in US currency 16 Vision2020 update and recommended action Direct membership requests and changes of Vision2020 Initiative Team address to the Treasurer/Membership Chairman Printed Back Issues of Planetarian 20 Factors influencing planetarium educator teaching IPS Back Publications Repository maintained by the Treasurer/Membership Chair methods at a science museum Beau Hartweg (See contact information on next page) 30 Characterizing fulldome planetarium projection systems Final Deadlines Lars Lindberg Christensen March: January 21 June: April 21 September: July 21 Eclipse Special Section: Get ready to chase the shadow in 2017 December: October 21 38 Short-term event, long-term results Ken Miller Associate Editors 42 A new generation to hook on eclipses Jay Ryan Book Reviews April S. -

Rotunda ROM Magazine Subject Index V. 1 (1968) – V. 42 (2009)

Rotunda ROM Magazine Subject Index v. 1 (1968) – v. 42 (2009) 2009.12.02 Adam (Biblical figure)--In art: Hickl-Szabo, H. "Adam and Eve." Rotunda 2:4 (1969): 4-13. Aesthetic movement (Art): Kaellgren, P. "ROM answers." Rotunda 31:1 (1998): 46-47. Afghanistan--Antiquities: Golombek, L. "Memories of Afghanistan: as a student, our writer realized her dream of visiting the exotic lands she had known only through books and slides: thirty-five years later, she recalls the archaeoloigical treasures she explored in a land not yet ruined by tragedy." Rotunda 34:3 (2002): 24-31. Akhenaton, King of Egypt: Redford, D.B. "Heretic Pharoah: the Akhenaten Temple Project." Rotunda 17:3 (1984): 8-15. Kelley, A.L. "Pharoah's temple to the sun: archaeologists unearth the remains of the cult that failed." Rotunda 9:4 (1976): 32-39. Alabaster sculpture: Hickl-Szabo, H. "St. Catherine of Alexandria: memorial to Gerard Brett." Rotunda 3:3 (1970): 36-37. Keeble, K.C. "Medieval English alabasters." Rotunda 38:2 (2005): 14-21. Alahan Manastiri (Turkey): Gough, M. "They carved the stone: the monastery of Alahan." Rotunda 11:2 (1978): 4-13. Albertosaurus: Carr, T.D. "Baby face: ROM Albertosaurus reveals new findings on dinosaur development." Rotunda 34:3 (2002): 5. Alexander, the Great, 356-323 B.C.: Keeble, K.C. "The sincerest form of flattery: 17th-century French etchings of the battles of Alexander the Great." Rotunda 16:1 (1983): 30-35. Easson, A.H. "Macedonian coinage and its Hellenistic successors." Rotunda 15:4 (1982): 29-31. Leipen, N. "The search for Alexander: from the ROM collections." Rotunda 15:4 (1982): 23-28. -

Appendix A: Educational Resources in Astronomy

Appendix A: Educational Resources in Astronomy A.I Planetariums, Museums, and Exhibits A.I.I Planetariums and Museums in the United Kingdom England - AAC Planetarium, Amateur Astronomy Centre, Bacup Road, Clough Bank, Tod morden, Lancs. OLl4 7HW. Tel: 0706816964. - British Museum, Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DG; Tel: 071-323 8395 ext. 395. Astronomical clocks. - British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, South Kensington, London SW7 5BD; Tel: 071-938 9123. Extensive meteorite collection. - Caird Planetarium, Old Royal Observatory, Greenwich, London SE 10. - William Day Planetarium, Plymouth Polytechnic, School of Maritime Studies, Ply- mouth PL4 8AA. Tel: 0752 264666. - Electrosonic Ltd., 815 Woolwich Road, London SE7 8LT. - Greenwich Planetarium, South Building, Greenwich Park, Greenwich, London SE 10. Tel: 081-858 1167. - William Herschel House and Museum, 19 New King Street, Bath, BA1 2Bl. Con tact: Dr. A.V. Sims, 30 Meadow Park, Bathford, Bath; Tel: 0225 859529. Open Mar-Oct daily 2-5 pm, Nov-Feb Sundays only, 2-5 pm. - lodrell Bank Planetarium and Visitor Center, Lower Withington, Nr. Macclesfield, Cheshire SK11 9DL; Tel: 0477 71339. - Kings Observatory, Kew, Old Deer Park, Richmond, Surrey TW9 2AZ. - University of Leicester, The Planetarium, Department of Astronomy, University Road, Leicester LEI 7RH; Tel: 0533 522522. - Liverpool Museum Planetarium, William Brown Street, Liverpool, Merseyside L3 8EN. Tel: 051-2070001 ext. 225. - London Planetarium, Marylebone Road, London NW1 5LR; Tel: 071-486 1121 (9:30--5:30), 071-486 1121 (recording). - City of London Polytechnic, The Planetarium, 100 Minories, Tower Hill, London EC3N BY. 071-283 1030. - London Schools Planetarium, John Archer School Building, Wandsworth Rd., Sutherland Grove, London SW18; Tel: 081-788 4253. -

ARCH NOTES Newsletter of the Ontario Archaeological Society (Incj

" ARCH NOTES Newsletter of The Ontario Archaeological Society (IncJ P.O. Box 241, Postal Station "P", Toronto, Ontario M5S 2S8 May, 1975 75-5 This Month's Meeting The last regular meeting of the O.A;S. before the summer will be held on Wednesday, May 21, 1975, at 8.00 p.m. in the lecture theatre of the McLaughlin Planetarium, Royal Ontario Museum. Mr. Robert Bowes, Director of the Planning and Research Branch, Heritage Conservation Division, Ministry of Culture and Recreation, will speak on 'the functioning of his branch and the way in which the new antiquities legislation will be implemented. There will be ample opportunities for questions. This should be a very informative meeting and all members of the Society are encouraged to attend. ARCH NOTES is published 7 - 10 times a year by the Ontario Archaeological Society. All e~quiries and contributions should be addressed to the Chairman, Arch Notes Committee, c/o 2 Minorca Place, Don Mills, Ontario M3A 2Z6. - 2 - ONTARIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY -- SYMPOSIUM 1975 The Ontario Archaeological Society wi II hold a Symposium on "Ontario Pre-iroquois Prehistory" on Saturday, October 18, 1975. The meeting will be one day In duration and will be held In the lecture theatre of the Mclaughlin Planetarium, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto. Papers, of about 20 minutes In length, are Invited for presentation at this meeting. A title, brief abstract, and tentative hotlce of audio-visual requirements should be sent to: Programme Convenor, Symposium Ontario Archaeological Society P.O. Box 241, Postal Station "P" Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2S8. Unless a request Is made for a particular session papers wll I be fitted Into the program according to topic. -

Welcome Guide >>>

Welcome Guide >>> Welcome Guide For Exchange and International Students This Guide will be used by both International Degree Seeking Students at Schulich in addition to Exchange Students studying at Schulich for one or two terms. Some information included will only pertain to one group of students and will be noted: International Degree seeking students will be referred to as “International students” Exchange students will be differentiated as “Exchange Students” Undergraduate students (BBA, iBBA) will be identified as “Undergraduate or UG” Graduate students (MBA, iMBA) will be differentiated as “Graduate or GR” Schulich School of Business York University 4700 Keele Street Toronto, Ontario Canada M3J 1P3 Phone: 416-736-5059 Fax: 416-650-8174 E-mail (Exchange): [email protected] E-mail (International): [email protected] 1 Welcome Guide >>> Table of Contents Student Services & International Relations 5 1 Before You Leave Home Your Visa Status 6 Length of Stay Country of Citizenship Other Activities Family Member Requirements Procedures Arriving at a Port of Entry 7 Immigration Check Canada Customs Information for International Students Plan Your Arrival in Toronto Packing Checklist 8 Plan for Student Life 9 Financial Planning Tuition Fee and Living Expenses Transferring Funds Plan for Canadian Weather 2 Living in Toronto Toronto 12 Quick Facts Moving Around in Toronto 13 Toronto Transit Commission Other Transportation Services Shopping in Toronto 14 Groceries Household Goods and Clothing Toronto Attractions 18 -

30 Hayden Street #807

30 Hayden Street #807 ● 4 piece bath located off the living room and across from the master. ● Ensuite laundry nicely tucked behind a closet door. ● Ownership of 1 locker Check out the YouTube video at Location! Location! Location! One of the highlights of 30 Hayden Street is its prime location! A quiet www.LovelyTorontoCondos.com street one block east of Yonge Street, west of Church just south of Bloor Street east! Upscale Living at Yonge & Bloor! A shopper’s delight! Downtown residents have a wide variety of shopping opportunities available to them. This mix includes Hudson’s Bay, Holt Move right into this fabulous1 bedroom condo located in “Tiffany Renfrew, high-end fashion stores on Bloor Street, trendy shops and Terrace”, a quiet boutique building in Toronto’s vibrant urban centre restaurants on Yonge Street and Church Street of Bloor-Yorkville! Bloor-Yorkville is acclaimed as Canada’s pre-eminent shopping district. An amazing floor plan with no wasted space! Recently upgraded Yorkville’s shops and restaurants are located in pretty Victorian houses on engineered hardwood floors, modern kitchen, private balcony Yorkville Avenue, Hazelton Avenue, Cumberland Street and Scollard Street. and owned locker! The Hazelton Lanes shopping centre located at 55 Avenue Road features over 100 exclusive shops and restaurants. 30 Hayden is the perfect location to do all your errands on foot. With Plenty of parks surround! Jesse Ketchum Park, Village of Yorkville Park a Walk Score of 100/100 you are just steps to all the action - located at 115 Cumberland Street known for winning numerous design Yonge & Bloor subway, shops and Yorkville’s high end shopping awards based on elements of Yorkville’s history as well as the Canadian and fine dining! landscape. -

NATIONAL NEWSLETTER C/O Ian Mcgregor, Mclaughlin Planetarium, 100 Queen’S Park, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C6

L45 N AT I O N A L N E W S L E T T E R October, 1977 The 1977 General Assembly. Photos by: E. Efston, J. Low, and I. McGregor L46 N AT I O N A L N E W S L E T T E R October, 1977 Editor: HARLAN CREIGHTON Assistant Editors: RALPH CHOU, J. D. FERNIE, NICK FRASER, P. MARMET, IAN MC GREGOR Art Director: BILL IRELAND Photographic Editor: RICHARD MCDONALD Regional News Editors: Centre and local news items, including Centre newsletters, should be sent to: Winnipeg and West: Paul Deans, 10707 University Ave., Edmonton, Alberta T6E 4P8 East of Winnipeg: Barry Matthews, 2237 Iris Street, Ottawa, Ontario K2C 1B9 Centres francais: Damien Lemay, 477 Ouest 15ieme rue, Rimouski, P.Q., G5L 5G1 Except as noted above, please submit all material and communications to: NATIONAL NEWSLETTER c/o Ian McGregor, McLaughlin Planetarium, 100 Queen’s Park, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C6 Deadline is two months prior to the month of issue. Editorials Thanks, Norman Readers will note that something is missing from the masthead this month. It is a name that first appeared on the masthead of the April, 1972 issue: the name of Norman Green. In his letter of resignation, Norman writes: “It has been a source of much satisfaction to have seen the NEWSLETTER grow from a news sheet to a multi-page publication; from a few items of news, to a really worthwhile, interesting and informative booklet.” All of us who have had the pleasure of working on the NEWSLETTER with Norman feel that a great deal of the credit for the success of the NEWSLETTER belongs to him. -

Space and Man, Senior Division

1969 Senior Division CONTENTS ABSTRACT. ii SALIENT FEATURES. 1 SYLLABUS . 3 The Moon . 3 Introduction to Flight . 4 The Current Space Scene. 4 Using Telescopes . 5 Life for Man in Space . 5 The Stellar Population . 6 Space Law and Politics . 6 The Way Into Space. 7 Great Ideas in Astronomy. 8 Fiction About Space. 8 Opening the Windows . 9 Rocketry. 9 Probing the Upper Atmosphere . 10 Further Themes for Student Choice. 11 The Impact of Space on Humanity . 11 Canada’s Contribution in Space . 12 Applications of Mathematics . 12 Origins . 13 Communication by Satellite . 13 The Planets. 14 Science and Technology. 14 Are We Alone . 15 IMPLEMENTING THE LOCAL PLAN 16 Determining the Program . 16 Sharing the Teaching. 16 Three Ways for One Theme . 16 Assessment. 20 Student Projects . 20 RESOURCES 22 Periodicals . 22 Books. 23 Other Learning Materials . 27 l Cover photo: National Research Council ABSTRACT TCiese guidelines to Space and Man are provided so that teachers and students will be able to plan for studies centered on space. The domain of the course extends from the earth’s surface through space to the farthest galaxies. In time, the domain stretches from the earliest astronomical observations to the present use of sophisticated probes and instruments. Just as important as the characteristics and exploration of space is the experience of mankind with space. Accordingly, the domain includes many aspects of man’s concern with space. For centuries men have looked up from the world at their feet, have pondered over origins, have speculated, and have recorded their thoughts in words and other art forms. -

Box # # of Items in Folder Name of Organization

Box # of Name of Organization (note: names that are underlined are filed by the underlined word in alphabetical order) Location # Items in Folder 1 1 Feike Asma. Organ recital. Toronto Toronto 1 ARS NOVA presents Theatre of Early Music presents "Star of Wonder" A Christmas Concert. Knox Presbyterian Church, Ottawa Ottawa. 1 ARS Omnia with Contemporary Music Projects presents The Inspiration of Greece and China. A trans-cultural Toronto contemporary music event. Kings College Circle, University of Toronto. 1 2 ARS Organi. Montreal 1 L'ARMUQ Quebec 1 1 A Benefit Concert for Women's College Hospital. John Arpin, [Pianist.]. Women's College Hospital 75th Anniversary, Toronto 1911-1986. Roy Thomson Hall, Toronto. 1 1 A Space - Toronto. Toronto 1 L'Academie Commerciale Catholique de Montreal. Montreal 1 1 L'Academie Des Lettres Et Des Sciences Humaine de la Society Royal Du Canada. [Ottawa?] 1 1 Academy of Dance. [Brantford, Ontario?] 2 Acadia University. Wolfville, Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia 1 2 ACME Theatre Company. Toronto 1 2 Acting Company. Toronto. Toronto 1 1 The Actors Workshop. Toronto. Toronto 1 1 Acustica International Montreal. Montreal 1 1 John Adams. New Music for synthesizers, solo bass and grand pianos by John Adams & Chan Ka Nin. Premiere Dance Toronto Theatre. New Music Concert. [Toronto.] 1 1 Adelaide Court Theatre. Toronto. Toronto 1 1 The Aeolian Town Hall. The London School Of Church Music. A Concert to honour the Silver Jubilee of Her Majesty London, Ontario Queen Elizabeth II. 1 Aetna Canada Young People's Concerts. Toronto. Toronto 1 2 Afternoon Concert Series. The Women's Musical Club of Toronto. -

A Case Study of the Governance of a U of T Capital Project: 90 Queen’S Park

Working Paper # 5 January 19, 2021 Miriam Hird-Younger and Mariana Valverde A Case Study of the Governance of a U of T Capital Project: 90 Queen’s Park What is a university? In Canada, as elsewhere, it is a centre for research and teaching, supported in part by public funds. It is also an employer, a producer of images, a subject of rankings, a real estate owner, a generator of revenues, and a hub in global networks of value and aspiration. But how does a university work? What exactly does it do? What are the powers and pressures, the practices and networks that constitute contemporary university worlds? An interdisciplinary team of faculty at the University of Toronto, we seek to discover the many worlds of our own institution, in collaboration with graduate and undergraduate students. We foreground the everyday experience of people who work or study in different corners of the institution, who live in its shadow, or respond to its public face. A pilot phase 2019-2021 has been funded by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Insight Discovery Grant #430-2019-00054 For more information about the project please contact [email protected] Visit our website at http://universityworlds.ca/ To cite this paper: Hird-Younger, Miriam and Mariana Valverde. (2021) “A Case Study of the Governance of a U of T Capital Project: 90 Queen’s Park.” Working Paper # 5, Discovering University Worlds, University of Toronto 2 Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................ -

History of the Royal Ontario Museum

100 Queen’s Park 416.586.8000 Toronto, Ontario www.rom.on.ca M5S 2C6 History of the Royal Ontario Museum • The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) was created with the signing of the ROM Act in the Ontario Legislature on April 16, 1912. The University of Toronto and the province each provided half of the funding. • The ROM opened its doors to the public on March 19, 1914. The building was built alongside Philosophers’ Walk and the main entrance faced Bloor Street. The building was officially opened by the Duke of Connaught, then Governor-General of Canada. This historic building originally housed five separate museums: the Royal Ontario Museums of Archaeology, Palaeontology, Mineralogy, Zoology, and Geology. Designed by Toronto-based architects Darling and Pearson, the graceful yellow brick structure incorporated architectural motifs from many times and cultures. • Two men are recognised as the ROM's founding fathers: Sir Byron Edmund Walker, a bank executive, civic activist, art collector, amateur palaeontologist, and a driving force behind the campaign to found a world-class public museum in Toronto and Dr. Charles Trick Currelly, an enterprising archaeologist, official antiquities collector for the Museum, and the Museum’s first Director of Archaeology. Photo: Donors Cockshutt, Osler and Warren visit Currelly on expedition in Egypt. • On October 12, 1933, the Museum expanded, and local newspapers reported that the building’s new wing was "a masterpiece of architecture." Designed by the Toronto firm of Chapman and Oxley, the Beaux-Arts style main façade now placed the main entrance facing Queen’s Park and completed the H-shaped basic floor plan of the ROM.