Ladbroke Grove Rail Accident

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Investigation of Rail Crew Fatigue and Well-Being

AN INVESTIGATION OF RAIL CREW FATIGUE AND WELL-BEING Jialin Fan A thesis submitted for the award of PhD, 2018 Word count: 57,263 SUMMARY Occupational fatigue is a severe problem in the rail industry, potentially jeopardising train crew health and train safety. The aim of this thesis was to investigate fatigue, its risk factors, and the associations between fatigue, well-being outcomes, and performance among staff members in the rail industry by conducting a series of studies. It also aimed to develop a usable online fatigue measure to examine fatigue in a real-life setting. A large-scale questionnaire survey was conducted to examine the prevalence of fatigue, identify the risk factors related to fatigue, and investigate the associations between fatigue and well-being outcomes among railway staff in general. An online experiment was then run to investigate the effects of time of day and workload on fatigue and the association between subjective fatigue and objective performance, with a student sample. Finally, a questionnaire exploring the potential risk factors and greater details for fatigue among railway staff was conducted, followed by a diary study investigating the effects of workload and other risk factors in the prediction of fatigue, and the impact of fatigue on objective performance in work life, with a railway staff sample. The results of this thesis suggested that job demands, especially mental workload and overtime work were the main predictors of different types of fatigue among train crew, although the risk factors for fatigue appeared to differ between job roles. Job demands, shift-work and other negative work characteristics were shown to increase fatigue, while positive work and individual characteristics were shown to play a buffering role against it. -

2005 Annual Return

Annual Return Reporting on the year 2004/05 31 July 2005 Page 2 Contents Executive summary.....................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Introduction..................................................................................................................................................................................................................16 Network Rail’s regulatory targets....................................................................................................................................................................20 Key performance indicators................................................................................................................................................................................24 Section 1 – Operational performance .........................................................................................................................................................27 Introduction...................................................................................................................................................................................................27 Summarised network-wide data (delays to major operators) ........................................................................................28 National delay data by cause...............................................................................................................................................................30 -

The Southall Rail Accident Inquiry Report Professor John Uff QC Freng

iealth 6 Safety Commission The Southall Rail Accident Inquiry Report - Professor John Uff QC FREng 2 Erratum The Southali Rail Accident Inquiry Report iSBN 0 7176 1757 2 Annex 09 Passengers & Staff believed to have sustained injury as a result of the accident Include 'Stuttard, Janis, Mrs Coach H' Delete ' Stothart, Chloe Helen, Miss Coach C' MlSC 210 HSE BOOKS 0 Crown copyright 2000 Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to: Copyright Unit, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, St Clernents House, 2-16 Colegate, Nofwich NR3 1BQ First published 2000 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. LIST OF CONTENTS Inquiry into Southall Railway Accident Preface Glossary Report Summary PART ONE THE ACCIDENT Chapter l How the accident happened Chapter 2 The emergency response Chapter 3 The track and signals Chapter 4 Why was the freight train crossing? Chapter 5 Driver competence and training Chapter 6 Why were the safety systems not working? Chapter 7 Why the accident happened PART TWO EVENTS SINCE SOUTJULL Chapter 8 The Inquiry and delay to progress Chapter 9 Reactions to Southall Chapter 10 Ladbroke Grove and its aftermath PART THREE WIDER SAFETY ISSUES Chapter 11 Crashworthiness and means of escape Chapter 12 Automatic Warning System (AWS) Chapter 13 Automatic Train Protection (ATP) Chapter 14 Railway Safety Issues PART FOUR CONCLUSION Chapter 15 Discussion and Conclusions Chapter 16 Lessons to be learned Chapter 17 Recommendations ANNEXES THIS Report follows an Inquiry held between September and December 1999 into the cause of a major rail accident which occurred on 19 September 1997 at Southall, 9 miles west of Paddington. -

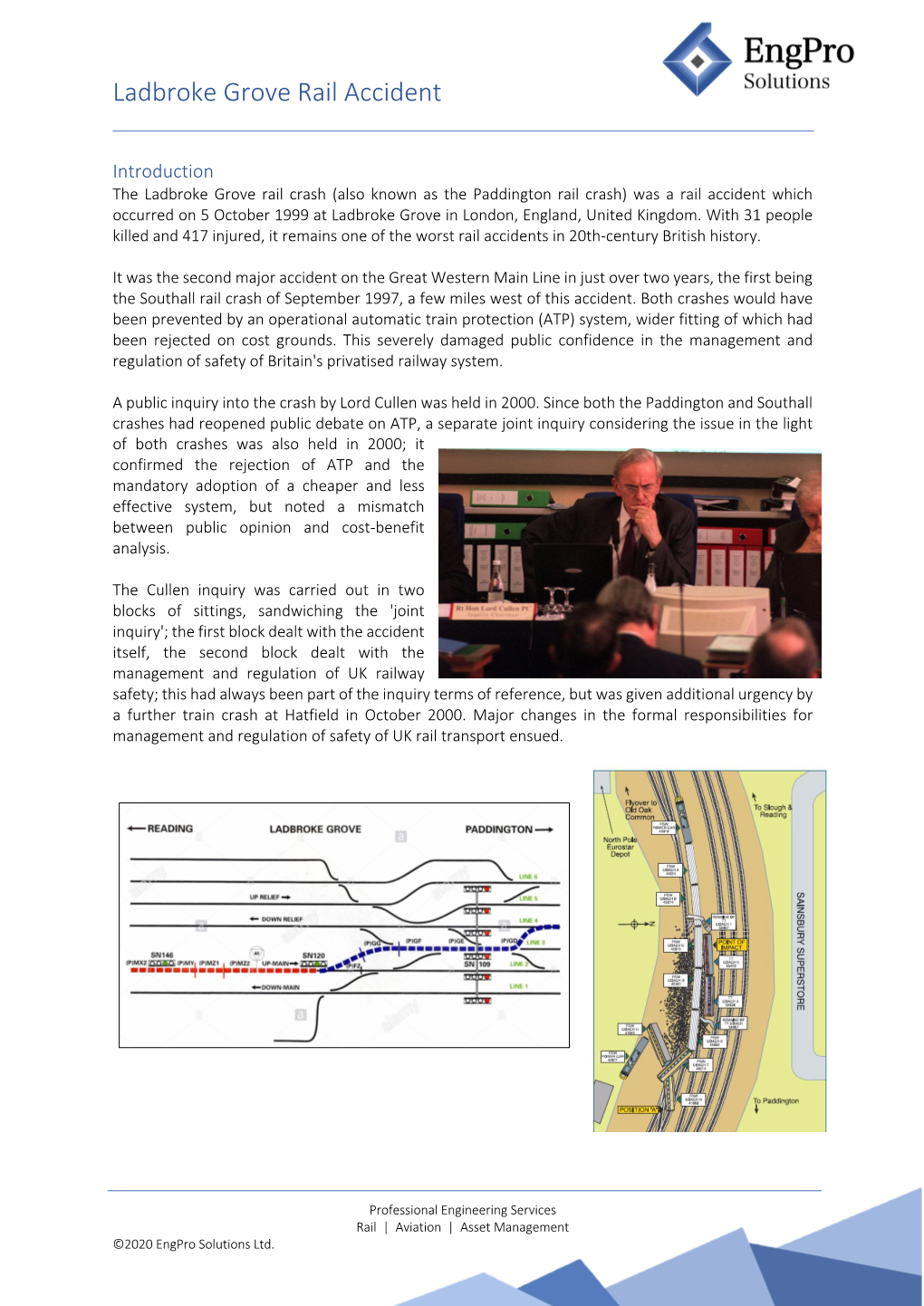

The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry

The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 1 Report The Rt Hon Lord Cullen PC The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 1 Report The Rt Hon Lord Cullen PC © Crown copyright 2000 Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to: Copyright Unit, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ First published 2001 ISBN 0 7176 2056 5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Front cover: View of crash site taken shortly after midday on 5 October 1999 ii Those who lost their lives Ladbroke Grove, 5 October 1999 Charlotte Andersen Derek Antonowitz Anthony Beeton Ola Bratlie Roger Brown Jennifer Carmichael Brian Cooper Robert Cotton Sam Di Lieto Shaun Donoghue Neil Dowse Cyril Elliott Fiona Grey Juliet Groves Sun Yoon Hah Michael Hodder Elaine Kellow Martin King Antonio Lacovara Rasak Ladipo Matthew Macaulay Delroy Manning John Northcott John Raisin David Roberts Allan Stewart Khawar Tauheed Muthulingam Thayaparan Andrew Thompson Bryan Tompson Simon Wood iii iv Contents List of plates vii Acknowledgements viii Chapters 1 Executive summary 1 2 The Inquiry 7 3 The journey before the crash 13 4 The crash 19 5 The actions of driver Hodder 51 6 The actions of the signallers 83 7 Railtrack and the infrastructure 103 8 Thames Trains and Automatic Train Protection 143 9 Thames Trains and driver management -

Read Book « Articles on Railway Accidents in London, Including

GMUC8RCSTCU4 \\ Kindle // Articles On Railway Accidents In London, including: King's Cross Fire, Ladbroke Grove... Articles On Railway Accidents In London, including: King's Cross Fire, Ladbroke Grove Rail Crash, Clapham Junction Rail Crash, Southall Rail Crash, Purley Station Rail Crash, Moorgate Tube Crash, Harr Filesize: 8.43 MB Reviews Here is the finest pdf i actually have go through until now. It is actually rally exciting throgh looking at time period. You will not truly feel monotony at anytime of your respective time (that's what catalogues are for regarding in the event you question me). (Bell Pacocha) DISCLAIMER | DMCA TIUHJNUNFKTA > eBook « Articles On Railway Accidents In London, including: King's Cross Fire, Ladbroke Grove... ARTICLES ON RAILWAY ACCIDENTS IN LONDON, INCLUDING: KING'S CROSS FIRE, LADBROKE GROVE RAIL CRASH, CLAPHAM JUNCTION RAIL CRASH, SOUTHALL RAIL CRASH, PURLEY STATION RAIL CRASH, MOORGATE TUBE CRASH, HARR To get Articles On Railway Accidents In London, including: King's Cross Fire, Ladbroke Grove Rail Crash, Clapham Junction Rail Crash, Southall Rail Crash, Purley Station Rail Crash, Moorgate Tube Crash, Harr eBook, make sure you refer to the link beneath and download the file or get access to additional information which might be relevant to ARTICLES ON RAILWAY ACCIDENTS IN LONDON, INCLUDING: KING'S CROSS FIRE, LADBROKE GROVE RAIL CRASH, CLAPHAM JUNCTION RAIL CRASH, SOUTHALL RAIL CRASH, PURLEY STATION RAIL CRASH, MOORGATE TUBE CRASH, HARR book. Hephaestus Books, 2016. Paperback. Book Condition: New. PRINT -

Network Management Statement 2000 - Railtrack PLC

Network Management Statement 2000 - Railtrack PLC (in Railway Administration) sitemap | contact us About Railtrack PLC Directors' Biographies Property & New Business Safety & Operations Regulatory Papers Corporate Documentation You are here: Home > Our Business > Corporate Documentation > Archive > Network Management Statement 2000 All of the documents with the symbol are available to download with the Adobe Acrobat reader. If you do not have this programme on your computer, click here to get it. Acrobat files are very easy to download and print. Just click on the document title and the file will open automatically. Chairman's Statement (13 kb) BACK TO REGULATORY PAPERS Volume 01 (3,414 kb) BACK TO CORPORATE Volume 02 (3,782 kb) DOCUMENTATION Regional Summary London and South East (1,967 kb) Regional Summary Midlands (904 kb) Regional Summary North (921 kb) Regional Summary Scotland (3,431 kb) Regional Summary South West (794 kb) Regional Summary Wales (761 kb) site by privacy statement | contact Railtrack PLC | legal notice | (c) 2001 Railtrack PLC vardus http://www.railtrack.co.uk/our_business/corp_doc/archive/network_man_state2000.cfm [25/06/2002 14:41:03] Developing rail services in London & the South East Developing rail services in London & the South East Base map ©MAPS IN MINUTES™ 1997 DEVELOPING RAIL SERVICES IN LONDON & THE SOUTH EAST 1 This is one of six regional documents which complement Railtrack’s Network Management Statement for 2000. It sets out a vision for the development of the rail network in London and South East England, covering: the role of the rail network in the economic and social development of the region; the improvements to which Railtrack is committed during the next ten years, ranging from maintenance and renewals of the existing network to major projects such as Thameslink 2000; our vision of how the network could be developed beyond those commitments – and a discussion of how such development could be achieved, in partnership with our stakeholders. -

The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry

The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 2 Report The Rt Hon Lord Cullen PC The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 2 Report The Rt Hon Lord Cullen PC © Crown copyright 2001 Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to: Copyright Unit, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ First published 2001 ISBN 0 7176 2107 3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. 1 Front cover: Taken from a photograph supplied by Milepost 92 /2 ii Contents Chapters 1 Executive summary 3 2 The Inquiry 11 3 The rail industry and its regulation 19 4 The implications of privatisation 39 5 The management and culture of safety 59 6 Railway Group Standards 79 7 Safety cases, accreditation and licensing 85 8 Railtrack and Railway Safety 109 9 The safety regulator 123 10 A rail industry safety body 155 11 An accident investigation body 161 12 Summary of recommendations 169 Appendices 1 Parties and their representatives 181 2 Witnesses 183 3 Principal documents 185 4 The relevant accidents 189 5 The models proposed by parties to the Inquiry 195 6 Safety regulation and accident investigation in aviation 203 7 Joint statement of experts on risk management 207 8 Abbreviations 215 Inquiry team 217 1 2 Chapter 1 Executive summary 1.1 As I explain in Chapter 2, this report relates to Part 2 of the Inquiry which was concerned, in regard to the railways, with the management of safety and the regulatory regime. -

HSE: the Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry

The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 1 Report The Rt Hon Lord Cullen PC The Ladbroke Grove Rail Inquiry Part 1 Report The Rt Hon Lord Cullen PC © Crown copyright 2000 Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to: Copyright Unit, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ First published 2001 ISBN 0 7176 2056 5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Front cover: View of crash site taken shortly after midday on 5 October 1999 ii Those who lost their lives Ladbroke Grove, 5 October 1999 Charlotte Andersen Derek Antonowitz Anthony Beeton Ola Bratlie Roger Brown Jennifer Carmichael Brian Cooper Robert Cotton Sam Di Lieto Shaun Donoghue Neil Dowse Cyril Elliott Fiona Grey Juliet Groves Sun Yoon Hah Michael Hodder Elaine Kellow Martin King Antonio Lacovara Rasak Ladipo Matthew Macaulay Delroy Manning John Northcott John Raisin David Roberts Allan Stewart Khawar Tauheed Muthulingam Thayaparan Andrew Thompson Bryan Tompson Simon Wood iii iv Contents List of plates vii Acknowledgements viii Chapters 1 Executive summary 1 2 The Inquiry 7 3 The journey before the crash 13 4 The crash 19 5 The actions of driver Hodder 51 6 The actions of the signallers 83 7 Railtrack and the infrastructure 103 8 Thames Trains and Automatic Train Protection 143 9 Thames Trains and driver management -

Review of the Balance of Competences Between the United Kingdom and the European Union

Review of the Balance of Competences between the United Kingdom and the European Union Transport: Consultation Response February 2014 The Department for Transport has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the Department’s website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact the Department. Department for Transport Great Minster House 33 Horseferry Road London SW1P 4DR Telephone 0300 330 3000 Website www.gov.uk/dft General enquiries https://forms.dft.gov.uk © Crown copyright 2014 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos or third-party material) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. 2 Contents Maritime 8 British Maritime Federation 8 British Ports Association 11 International Group of P&I Clubs 15 Lloyds Register 18 Maritime Workshop 22 Port of Dover 27 Royal Yachting Association (RYA) 29 Trinity House 35 UK Chamber of Shipping 38 UK Major -

Country Together

Annual Return 2007 Delivering for you Network Rail helps bring the country together. We own, operate, maintain and invest in Britain’s rail network. Increasingly we are delivering improved standards of safety, reliability and efficiency. This benefits our customers and society at large. Every day. Everywhere. Contents Executive summary 1 Earthwork remediation (M28) 118 Introduction 9 Tunnel remediation (M29) 119 Targets 13 Key performance indicators (KPIs) 16 Section 5 Safety & Environment 122 Accident Frequency Rate 122 Section 1 – Operational performance and Infrastructure wrong side failures 123 stakeholder relationships 18 Level crossing misuse 124 Public performance measure (PPM) 19 Signals passed at danger (SPADs) 125 Summarised network-wide data (delays to major operators) 20 Operating irregularities 127 National data by delay category grouping 25 Criminal damage 128 Results for operating routes by delay category 29 Safety and environment enhancements 129 Asset failure 38 Customer satisfaction – passenger and freight operators 45 Section 6 – Expenditure and Efficiency 131 Supplier Satisfaction 46 Network total expenditure 131 Doing Business with Network Rail 47 Route 1 Kent 134 Joint Performance Process 47 Route 2 Brighton Main Line and Sussex 135 Route Utilisation Strategies (RUSs) 50 Route 3 South West Main Line 136 Route 4 Wessex Routes 137 Section 2 – Network capability 52 Route 5 West Anglia 138 Linespeed capability (C1) 53 Route 6 North London Line and Thameside 139 Gauge capability (C2) 58 Route 7 Great Eastern 140 Route -

RCHS Chronology of Modern Transport in the British Isles 1945

RCHS Chronology of Modern Transport in the British Isles 1945–2015 Introduction This chronology is intended to set out some of the more significant events in the recent history of transport and communication, with particular reference to public transport, in the British Isles since the end of 1944. It cannot hope to cover the closure or opening of every branch railway or canal, the sale of every bus company, nor the coming and going of every pertinent office holder. The hope is that it does contain details of the principal legislative and organisational changes affecting transport – in particular the shifts between private and public ownership which have characterised the industry within this period – together with some notable ‘firsts’, ‘lasts’ and other significant events, especially those which exhibit trends. A very few overseas events are included (in italics), either because they had a British relationship, or for comparative purposes. Conventions Dates are, where appropriate, the first or last occasion on which an ordinary member of the public could make full use of the facility: official and partial openings on different dates are in general confined to parentheses; and ‘closed with effect from’ (wef) dates are quoted only where the actual last day of service has not been certainly established. Dates assigned to statutes are those of assent unless stated otherwise. ‘First’, ‘last’ or similar qualifiers mean ‘in Britain’ unless otherwise indicated. ‘Commercial’ is used, rather loosely, as a qualifier to exclude experimental, enthusiast, heritage, leisure or similar operations. Forms of name are those in use at the date of the event. -

A Better Railway for Britain

A Better Railway for Britain Re-unifying our railways under public ownership A Report by Bring Back British Rail October 2016 1993One RAILWAYS ofin Britishthe most parliamentary ACT heavily amended history bills SEPTEMBER 1997 A TimelineofFailures Rail Privatisation: Southall rail crash kills seven people and injures 139.1 Great Western Trains is fined £1.5 million for health and safety violations.2 DECEMBER 1998 National Audit Office report finds that taxpayers lost £1.5 billion as a result of the government’s rushed sale of shares in Railtrack in May 1996,3 (in 2016, the equivalent of £2.3 billion). OCTOBER 1999 Ladbroke Grove rail crash kills 31 people and injures 52. Thames Trains’ poor driver training is cited as a major contributing factor.4 OCTOBER 2000 Hatfield rail crash kills four and injures 70. Railtrack’s lack of knowledge and failure to maintain its track is blamed,5 leading to plans to transform the company into a ‘not-for-profit’ trust.6 OCTOBER 2000 Strategic Rail Authority strips Connex of the South Central rail franchise, following criticism of poor customer service and financial management.7 2 A Better Railway for Britain | Re-unifying our railways under public ownership OCTOBER 2001 After severe financial difficulties, Railtrack is placed into administration by Transport Secretary Stephen Byers8 and replaced by the arms-length public body Network Rail in 2002. A Better Railway for Britain | Re-unifying our railways underpublic ownership Britain|Re-unifyingourrailways for A BetterRailway MAY 2002 Potters Bar rail crash