Investigating Reproductive Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

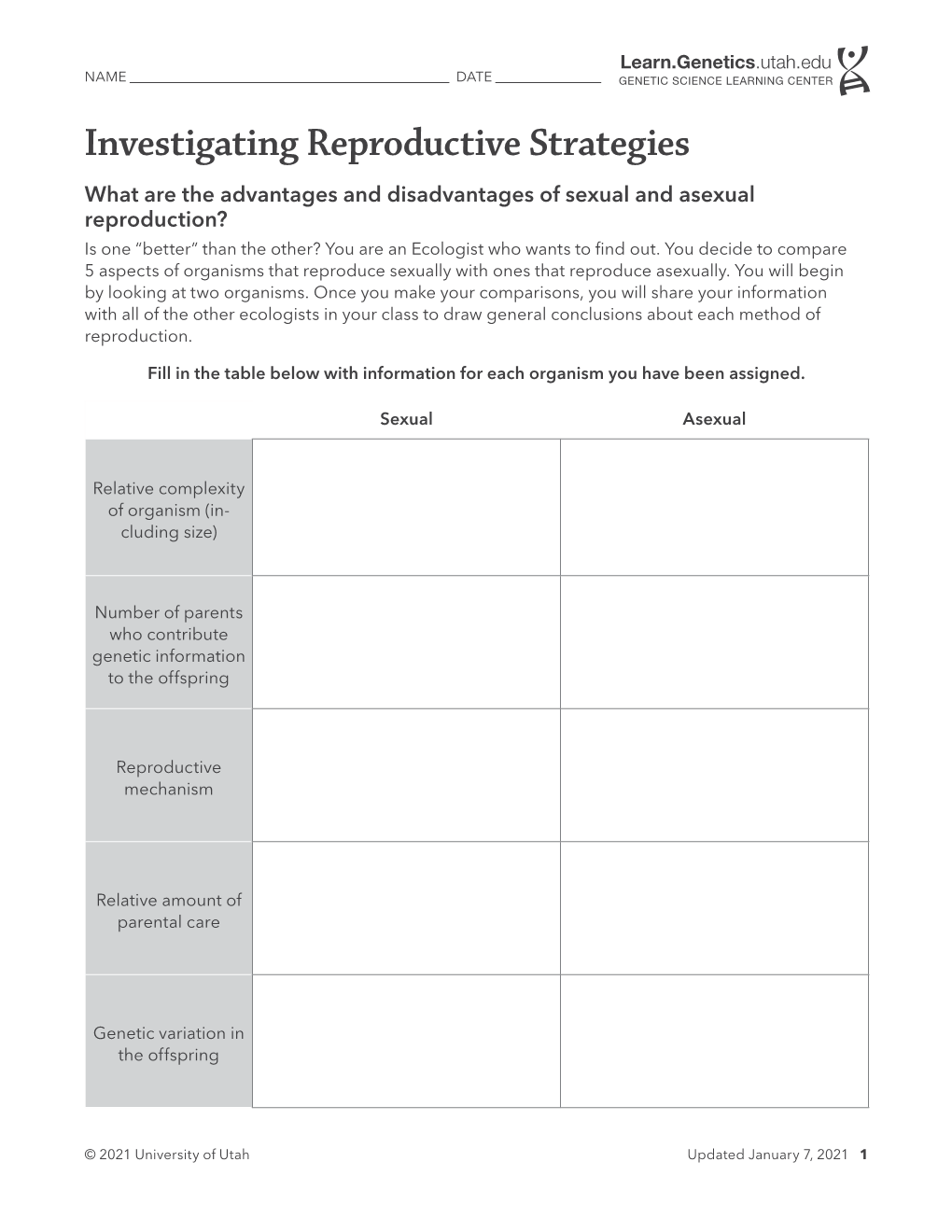

Investigating Reproductive Strategies

Teacher Guide Investigating Reproductive Strategies Abstract Students work in pairs to compare five aspects of an organism that reproduces sexually with one that reproduces asexually. As a class, students share their comparisons and generate a list of gener- al characteristics for each mode of reproduction, and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of both. Learning Objectives • There are two modes of reproduction, sexual and asexual. • There are advantages and disadvantages to both sexual and asexual reproduction. Estimated time • Class time 50 minutes • Prep time 10 minutes Materials Copies of student pages Instructions 1. Divide students into pairs. 2. Hand each pair: • The Investigating Reproductive Strategies worksheet • 2 organism descriptions - one for an organism that reproduces sexually and one for an organ- ism that reproduces either asexually or using both strategies - (see chart below). Sexual Asexual Both Sexual and Asexual Reproductive Blue-headed wrasse Amoeba Brittle star strategies Duck leech Salmonella Meadow garlic used by organisms Grizzly bear Whiptail Lizard Spiny water fleas described in Leafy sea dragon this activity Red kangaroo Sand scorpion 3. Instruct each pair to read about their assigned organisms and complete the comparison table on the Investigating Reproductive Strategies worksheet. 4. When all pairs have completed the comparison table, have them post their tables around the room. © 2020 University of Utah Updated July 29, 2020 1 5. Ask students to walk around the room and read the comparison tables with the goal of creating a list of general characteristics for organisms that reproduce sexually and one for organisms that reproduce asexually. 6. As a class, compile lists of general characteristics for organisms that reproduce sexually and asexually on the board. -

Jacksonville, Florida 1998 Odmds Benthic Community Assessment

JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA 1998 ODMDS BENTHIC COMMUNITY ASSESSMENT Submitted to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 4 61 Forsyth St. Atlanta, Georgia 30303 Prepared by Barry A. Vittor & Associates, Inc. 8060 Cottage Hill Rd. Mobile, Alabama 36695 (334) 633-6100 November 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ………………………………………….……………………………3 LIST OF FIGURES ……………………..………………………………………………..4 1.0 INTRODUCTION ………..…………………………………………………………..5 2.0 METHODS ………..…………………………………………………………………..5 2.1 Sample Collection And Handling ………………………………………………5 2.2 Macroinfaunal Sample Analysis ……………………………………………….6 3.0 DATA ANALYSIS METHODS ……..………………………………………………6 3.1 Assemblage Analyses ..…………………………………………………………6 3.2 Faunal Similarities ……………………………………………………….…….8 4.0 HABITAT CHARACTERISTICS ……………………………………………….…8 5.0 BENTHIC COMMUNITY CHARACTERIZATION ……………………………..9 5.1 Faunal Composition, Abundance, And Community Structure …………………9 5.2 Numerical Classification Analysis …………………………………………….10 5.3 Taxa Assemblages …………………………………………………………….11 6.0 1995 vs 1998 COMPARISONS ……………………………………………………..11 7.0 SUMMARY ………………………………………………………………………….13 8.0 LITERATURE CITED ……………………………………………………………..16 2 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Station locations for the Jacksonville, Florida ODMDS, June 1998. Table 2. Sediment data for the Jacksonville, Florida ODMDS, June 1998. Table 3. Summary of abundance of major taxonomic groups for the Jacksonville, Florida ODMDS, June 1998. Table 4. Abundance and distribution of major taxonomic groups at each station for the Jacksonville, Florida ODMDS, June 1998. Table 5. Abundance and distribution of taxa for the Jacksonville, Florida ODMDS, June 1998. Table 6. Percent abundance of dominant taxa (> 5% of the total assemblage) for the Jacksonville, Florida ODMDS, June 1998. Table 7. Summary of assemblage parameters for the Jacksonville, Florida ODMDS stations, June 1998. Table 8. Analysis of variance table for density differences between stations for the Jacksonville, Florida ODMDS stations, June 1998. -

REVIEW Physiological Dependence on Copulation in Parthenogenetic Females Can Reduce the Cost of Sex

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 2004, 67, 811e822 doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.05.014 REVIEW Physiological dependence on copulation in parthenogenetic females can reduce the cost of sex M. NEIMAN Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington (Received 6 December 2002; initial acceptance 10 April 2003; final acceptance 27 May 2003; MS. number: ARV-25) Despite the two-fold reproductive advantage of asexual over sexual reproduction, the majority of eukaryotic species are sexual. Why sex is so widespread is still unknown and remains one of the most important unanswered questions in evolutionary biology. Although there are several hypothesized mechanisms for the maintenance of sex, all require assumptions that may limit their applicability. I suggest that the maintenance of sex may be aided by the detrimental retention of ancestral traits related to sexual reproduction in the asexual descendants of sexual taxa. This reasoning is based on the fact that successful reproduction in many obligately sexual species is dependent upon the behavioural, physical and physiological cues that accompany sperm delivery. More specifically, I suggest that although parthenogenetic (asexual) females have no need for sperm per se, parthenogens descended from sexual ancestors may not be able to reach their full reproductive potential in the absence of the various stimuli provided by copulatory behaviour. This mechanism is novel in assuming no intrinsic advantage to producing genetically variable offspring; rather, sex is maintained simply through phylogenetic constraint. I review and synthesize relevant literature and data showing that access to males and copulation increases reproductive output in both sexual and parthenogenetic females. These findings suggest that the current predominance of sexual reproduction, despite its well-documented drawbacks, could in part be due to the retention of physiological dependence on copulatory stimuli in parthenogenetic females. -

Tube Epifaum of the Polychaete Phyllopchaetopterus Socialis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository Open Access to Scientific Information from Embrapa Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science (1995) 41, 91–100 Tube epifauna of the Polychaete Phyllochaetopterus socialis Claparède Rosebel Cunha Nalessoa, Luíz Francisco L. Duarteb, Ivo Pierozzi Jrc and Eloisa Fiorim Enumod aDepartamento de Zoologia, CCB, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, 50670-901, Recife, PE, Brazil, bDepartamento de Zoologia, Instituto Biologia, C.P. 6109, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 13.081-970, Campinas, SP, Brazil, cEmbrapa, NMA, Av. Dr. Julio Soares de Arruda, 803 CEP 13.085, Campinas, SP, Brazil and dProtebras, Rua Turmalina, 79 CEP 13.088, Campinas, SP, Brazil Received 8 October 1992 and in revised form 22 June 1994 Keywords: Polychaeta; tubes; faunal association; epifauna; São Sebastião Channel; Brazil Animals greater than 1 mm, found among tangled tubes of Phyllochaetopterus socialis (Chaetopteridae) from Araçá Beach, São Sebastião district, Brazil, were studied for 1 year, with four samples in each of four seasons. They comprised 10 338 individuals in 1722·7 g dry weight of polychaete tubes, with Echino- dermata, Polychaeta (not identified to species) and Crustacea as the dominant taxa. The Shannon–Wiener diversity index did not vary seasonally, only two species (a holothurian and a pycnogonid) showing seasonal variation. Ophiactis savignyi was the dominant species, providing 45·5% of individuals. Three other ophiuroids, the holothurian Synaptula hidriformis, the crustaceans Leptochelia savignyi, Megalobrachium soriatum and Synalpheus fritzmuelleri, the sipunculan Themiste alutacea and the bivalve Hiatella arctica were all abundant, but most of the 68 species recorded occurred sparsely. -

List of Marine Alien and Invasive Species

Table 1: The list of 96 marine alien and invasive species recorded along the coastline of South Africa. Phylum Class Taxon Status Common name Natural Range ANNELIDA Polychaeta Alitta succinea Invasive pile worm or clam worm Atlantic coast ANNELIDA Polychaeta Boccardia proboscidea Invasive Shell worm Northern Pacific ANNELIDA Polychaeta Dodecaceria fewkesi Alien Black coral worm Pacific Northern America ANNELIDA Polychaeta Ficopomatus enigmaticus Invasive Estuarine tubeworm Australia ANNELIDA Polychaeta Janua pagenstecheri Alien N/A Europe ANNELIDA Polychaeta Neodexiospira brasiliensis Invasive A tubeworm West Indies, Brazil ANNELIDA Polychaeta Polydora websteri Alien oyster mudworm N/A ANNELIDA Polychaeta Polydora hoplura Invasive Mud worm Europe, Mediterranean ANNELIDA Polychaeta Simplaria pseudomilitaris Alien N/A Europe BRACHIOPODA Lingulata Discinisca tenuis Invasive Disc lamp shell Namibian Coast BRYOZOA Gymnolaemata Virididentula dentata Invasive Blue dentate moss animal Indo-Pacific BRYOZOA Gymnolaemata Bugulina flabellata Invasive N/A N/A BRYOZOA Gymnolaemata Bugula neritina Invasive Purple dentate mos animal N/A BRYOZOA Gymnolaemata Conopeum seurati Invasive N/A Europe BRYOZOA Gymnolaemata Cryptosula pallasiana Invasive N/A Europe BRYOZOA Gymnolaemata Watersipora subtorquata Invasive Red-rust bryozoan Caribbean CHLOROPHYTA Ulvophyceae Cladophora prolifera Invasive N/A N/A CHLOROPHYTA Ulvophyceae Codium fragile Invasive green sea fingers Korea CHORDATA Actinopterygii Cyprinus carpio Invasive Common carp Asia CHORDATA Ascidiacea -

Sex-Specific Spawning Behavior and Its Consequences in an External Fertilizer

vol. 165, no. 6 the american naturalist june 2005 Sex-Specific Spawning Behavior and Its Consequences in an External Fertilizer Don R. Levitan* Department of Biological Science, Florida State University, a very simple way—the timing of gamete release (Levitan Tallahassee, Florida 32306-1100 1998b). This allows for an investigation of how mating behavior can influence mating success without the com- Submitted October 29, 2004; Accepted February 11, 2005; Electronically published April 4, 2005 plications imposed by variation in adult morphological features, interactions within the female reproductive sys- tem, or post-mating (or pollination) investments that can all influence paternal and maternal success (Arnqvist and Rowe 1995; Havens and Delph 1996; Eberhard 1998). It abstract: Identifying the target of sexual selection in externally also provides an avenue for exploring how the evolution fertilizing taxa has been problematic because species in these taxa often lack sexual dimorphism. However, these species often show sex of sexual dimorphism in adult traits may be related to the differences in spawning behavior; males spawn before females. I in- evolutionary transition to internal fertilization. vestigated the consequences of spawning order and time intervals One of the most striking patterns among animals and between male and female spawning in two field experiments. The in particular invertebrate taxa is that, generally, species first involved releasing one female sea urchin’s eggs and one or two that copulate or pseudocopulate exhibit sexual dimor- males’ sperm in discrete puffs from syringes; the second involved phism whereas species that broadcast gametes do not inducing males to spawn at different intervals in situ within a pop- ulation of spawning females. -

Patterns of Sexual and Asexual Reproduction in the Brittle Star Ophiactis Savignyi in the Florida Keys

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 230: 119–126, 2002 Published April 5 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Patterns of sexual and asexual reproduction in the brittle star Ophiactis savignyi in the Florida Keys Tamara M. McGovern* Department of Biological Science, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida 32306-1100, USA ABSTRACT: Many plant and animal species reproduce both sexually and asexually. These 2 repro- ductive modes are both likely to be costly and, in many species, they occur at different times of the year. Here, I present information on the sexual and asexual reproductive biology of the brittle star Ophiactis savignyi (Echinodermata, Ophiuroidea) in the Florida Keys, USA. Small brittle stars (less than 3 mm) are almost always non-mature, and non-mature individuals are more likely to have recently undergone clonal division than mature brittle stars. Males appear to have a lower size threshold for sexual maturity than do females, but the sexes do not differ in the recency of clonal divi- sion. The greatest proportion of mature brittle stars was observed in the late summer through fall in all 3 years of the study. The incidence of asexual reproduction increases in the late fall through late winter. It therefore appears that brittle stars are more likely to split after the sexual reproductive sea- son. The onset of cloning as the sexual reproductive season ends may result from differences in the time of year in which each mode confers the greatest fitness benefit or may arise from energetic trade-offs between the 2 modes of reproduction. KEY WORDS: Asexual reproduction · Sexual reproduction · Ophiactis savignyi · Size at reproduction · Seasonality Resale or republication not permitted without written consent of the publisher INTRODUCTION Sexual reproduction typically requires a major ener- getic investment (see e.g. -

Isolation and Identification of Bacterial Endosymbionts in the Brooding Brittle Star Amphipholis Squamata

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Honors Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2016 Isolation and identification of bacterial endosymbionts in the brooding brittle star Amphipholis squamata Abbey Rose Tedford University of New Hampshire - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/honors Part of the Bacteriology Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, Environmental Microbiology and Microbial Ecology Commons, Marine Biology Commons, and the Organismal Biological Physiology Commons Recommended Citation Tedford, Abbey Rose, "Isolation and identification of bacterial endosymbionts in the brooding brittle star Amphipholis squamata" (2016). Honors Theses and Capstones. 273. https://scholars.unh.edu/honors/273 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Isolation and identification of bacterial endosymbionts in the brooding brittle star Amphipholis squamata Abbey Rose Tedford, Kathleen M. Morrow, Michael P. Lesser Department of Molecular, Cellular and Biological Sciences, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03824 Abstract: Symbiotic associations with subcuticular bacteria (SCB) have been identified and studied in numerous echinoderms, including the SCB of the brooding brittle star, Amphipholis squamata. These SCB, however, have not been studied using current next generation sequencing technologies. Previous studies on the SCB of A. squamata placed these bacteria in the genus Vibrio (γ-Proteobacteria), but subsequent studies suggested that the SCB are primarily composed of α-Proteobacteria. -

Independent Research Projects Tropical Marine Biology Class Summer 2012, La Paz, México

Independent Research Projects Tropical Marine Biology Class Summer 2012, La Paz, México Western Washington University Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur Title pp Effects of human activity, light levels and weather conditions on the feeding behaviors of Pelecanus occidentalis in Pichilingue Bay, Baja California Sur, Mexico……………………………………………………………….....3 Predation of the brittle star Ophiocoma alexandri in the La Paz region, Baja California Sur, Mexico………………………………………………….……………..24 The effect of water temperature and disturbance on the movement of Nerita scabricosta in the intertidal zone…………………………………..….………….....38 Nocturnal behavior in Euapta godeffroyi (accordion sea cucumber): the effects of light exposure and time of day………………………………………….…....51 Queuing behavior in the intertidal snail Nerita scabricosta in the Gulf of California…………………………………………………………………....62 The effects of sunscreen on coral bleaching of the genus Pocillopora located in Baja California Sur……………………………………………………….….…76 Effect of tide level on Uca Crenulata burrow distribution and burrow shape………….…89 Habitat diversity and substratum composition in relation to marine invertebrate diversity of the subtidal in Bahía de La Paz, B.C.S, México………….……110 Ophiuroids (Echinodermata: Ophiuroidea) associated with sponge Mycale sp. (Poecilosclerida: Mycalidae) in the Bay of La Paz, B.C.S., México.…………….………128 Human disturbance on the abundance of six common species of macroalgae in the Bay of La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico.…………….……..…137 1 Summer 2012 Class Students: -

The Echinoderm Fauna of Turkey with New Records from the Levantine Coast of Turkey

Proc. of middle East & North Africa Conf. For Future of Animal Wealth THE ECHINODERM FAUNA OF TURKEY WITH NEW RECORDS FROM THE LEVANTINE COAST OF TURKEY Elif Özgür1, Bayram Öztürk2 and F. Saadet Karakulak2 1Faculty of Fisheries, Akdeniz University, TR-07058 Antalya, Turkey 2İstanbul University, Faculty of Fisheries, Ordu Cad.No.200, 34470 Laleli- Istanbul, Turkey Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The echinoderm fauna of Turkey consists of 80 species (two Crinoidea, 22 Asteroidea, 18 Ophiuroidea, 20 Echinoidea and 18 Holothuroidea). In this study, seven echinoderm species are reported for the first time from the Levantine coast of Turkey. These are, five ophiroid species; Amphipholis squamata, Amphiura chiajei, Amphiura filiformis, Ophiopsila aranea, and Ophiothrix quinquemaculata and two echinoid species; Echinocyamus pusillus and Stylocidaris affinis. Turkey is surrounded by four seas with different hydrographical characteristics and Turkish Straits System (Çanakkale Strait, Marmara Sea and İstanbul Strait) serve both as a biological corridor and barrier between the Aegean and Black Seas. The number of echinoderm species in the coasts of Turkey also varies due to the different biotic environments of these seas. There are 14 echinoderm species reported from the Black Sea, 19 species from the İstanbul Strait, 51 from the Marmara Sea, 71 from the Aegean Sea and 42 from the Levantine coasts of Turkey. Among these species, Asterias rubens, Ophiactis savignyi, Diadema setosum, and Synaptula reciprocans are alien species for the Turkish coasts. Key words: Echinodermata, new records, Levantine Sea, Turkey. Cairo International Covention Center , Egypt , 16 - 18 – October , (2008), pp. 571 - 581 Elif Özgür et al. -

Echinoderm Species of Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary

CORAL CAP SPECIES OF FLOWER GARDEN BANKS NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Classification Common name Scientific Name Echinoderms Brittle Stars Amphiodia pulchella Amphioplus tumidus Asteroschema sp. Astrocyclus caecilia Basket Star Astrophyton muricatum Asteroporpa annulata Gorgonocephalus sp. Ophiactis algicola Five-armed Ophiactis Ophiactis quinqueradia Savigny's Brittle Star Ophiactis savignyi Blunt-spined/Spiny Brittle Star Ophiocoma echinata Red Ophiocoma Ophiocoma wendtii Ophiocomella ophiactoides Banded-arm/Harlequin Brittle Star Ophioderma appressum Serpent Star Ophioderma brevispinum Ruby Brittle Star Ophioderma rubicundum Scaly Brittle Star, Red Serpent Star Ophioderma squamosissimum Elegant Brittle Star Ophiolepis elegans ?Ophiophragmus sp. Reticulated Brittle Star Ophionereis reticulata Ophiostigma isacanthus Angular Brittle Star Ophiothrix angulata Suenson's/Sponge Brittle Star Ophiothrix suensonii Ophiurochaeta littoralis Sea Cucumbers Five-toothed Sea Cucumber Actinopyga agassizii Beaded Sea Cucumber Euapta lappa Holothuria lentiginosa Chocolate Chip/Three-rowed Cucumber Isostichopus (Stichopus) badionotus Cucumber Thyone pseudofusus Sea Stars Astropecten comptus Asterinopsis lymani Asterinopsis pilosis Coronaster briareus Goniaster tessellatus Common Comet Star Linckia guildingii Linckia nodosa Guilding's/Comet Star Ophidiaster guildingii Sclerasterias contorta CORAL CAP SPECIES OF FLOWER GARDEN BANKS NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Classification Common name Scientific Name Sea Urchins Purple-spined Sea Urchin Arbacia punctulata Centrostephanus longispinus rubricingulus Coelopleurus floridanus Long-spined Sea Urchin Diadema antillarum Slate-pencil Urchin Eucidaris tribuloides Genocidaris maculata Lytechinus euerces Green/Variegated Urchin Lytechinus variegatus Red Heart Urchin Meoma ventricosa Paraster doederleini Stained Collector Urchin Pseudoboletia maculata maculata Red Sea Urchin Stylocidaris affinis . -

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE SAN AGUSTÍN DE AREQUIPA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE BIOLOGÍA Riqueza Y

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE SAN AGUSTÍN DE AREQUIPA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE BIOLOGÍA Riqueza y tipos de hábitat de equinodermos en la Región Arequipa al 2017 Tesis para optar el título profesional de Biólogo presentado por el Bachiller en Ciencias Biológicas: Michael Leopoldo Espinoza Roque Asesor: Blgo. Dr. Graciano Alberto Del Carpio Tejada AREQUIPA – PERÚ 2018 1 ____________________________________ Blgo. Dr. Graciano Alberto Del Carpio Tejada ASESOR 2 DEDICATORIA A la memoria de mi padre, Leopoldo Espinoza Ramos, por todo su cariño, comprensión y sacrificio, sé que estaría feliz al verme cumplir esta meta. 3 AGRADECIMIENTOS A la Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa (UNSA INVESTIGA), por el soporte financiero, con recursos del canon de la UNSA, para que se realice el presente proyecto de investigación (Contrato de financiamiento N° 156 – 2016 – UNSA), y un especial agradecimiento al Blgo. Luis Alberto Ponce Soto por la paciencia y apoyo en el acompañamiento y monitoreo de mi proyecto. A mi asesor de tesis, Blgo. Dr. Graciano Alberto Del Carpio Tejada, por su apoyo incondicional durante el desarrollo del presente trabajo de investigación. A la Blga. Rosaura Gonzales Juárez, por su contribución al inicio de este proyecto y sus enseñanzas y consejos que han aportado en mi formación profesional. Al Blgo. Franz Cardoso Pacheco, por permitirme consultar material de la colección científica del Laboratorio de Biología y Sistemática de Invertebrados Marinos de la Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas (LaBSIM), de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. A Gustavo Robles Fernández, Por permitirme consultar material del Instituto de Investigación y Desarrollo Hidrobiológico de la Universidad Nacional de San Agustín (INDEHI – UNSA).