Moneyless Menifesto (Mark Boyle).Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guía Viajar 2022

2021 Viajar VIAJAR VIAJAR DOCUMENTACIÓN CARNETS Y DESCUENTOS PASAPORTE O DOCUMENTO DE IDENTIDAD Si vas a desplazarte por la Unión Europea en Llévalos también cuando viajes dentro de la UE tus vacaciones, te ofrecemos algunos recur- En todo el mundo puedes disfrutar de las ventajas sos de interés para planificarte tu viaje, des- y descuentos de estos carnés. Estos te ofrecen la SEGUROS cuentos y posibilidades para la realización posibilidad de hospedarte, visitar museos o reali- del desplazamiento, el alojamiento e infor- No olvides llevar contigo la documentación de los zar compras a un precio más barato. seguros de viaje, salud y automóvil. mación necesaria en caso de tener algún per- cance. CARNÉ JOVEN EURO<26 TARJETA SANITARIA EUROPEA Esta tarjeta permite recibir asistencia sanitaria en los paí- www.renfe.com/viajeros/tarifas/CarneJoven.html ses de la UE. www.seg-social.es/wps/portal/wss/internet/Trabajadores/ PrestacionesPensionesTrabajadores/10938/11566/1761 CARNÉ INTERNACIONAL DE ESTUDIANTE (ISIC) TUS DERECHOS En la página web de la Comisión Europea podrás compro- www.isic.es bar los derechos que te asisten cuando viajas. http://europa.eu/youreurope/citizens/travel/index_es.htm CARNÉ INTERNACIONAL GO-25 (IYTC) COVID www.isic.es/estudiante/ infórmate de las medidas vigentes en el portal de la comi- sión donde podrás saber las restricciones y requisitos de los países UE. https://reopen.europa.eu/es CARNÉ INTERNACIONAL DE ALBERGUISTA www.inturjoven.com/carnets/carnets-de-alberguistas BREXIT – REINO UNIDO En el siguiente enlace podrás comprobar si necesitar apli- car una Visa según tus circunstancias para viajar a Reino Unido: https://www.gov.uk/check-uk-visa VIAJAR ALOJAMIENTO DESPLAZARTE HOTELES. -

Bewelcome.Org

Bewelcome.org – a non-profit democratic hospex service set up for growth. Rustam Tagiew Alumni of TU Bergakademie Freiberg [email protected] Abstract—This paper presents an extensive data-based anal- the difference between the terms user, which is basically a ysis of the non-profit democratic hospitality exchange service profile owner, and member – not every website user had a bewelcome.org. We hereby pursuit the goal of determining the real-life interaction with other members in order to be called factors influencing its growth. It also provides general insights a member. Members are a subset of users. on internet-based hospitality exchange services. The other investi- Hospex services always started as non-profit, donation gated services are hospitalityclub.org and couchsurfing.org. Com- and volunteer-driven organizations, since making profit on munities using the three services are interconnected – comparing their data provides additional information. gratuitous hospitality is considered unethical in modern culture. Nevertheless, business on gratuitous hospitality is common at least in mediation of au-pairs to host families [9, I. INTRODUCTION eg.]. Unfortunately, we can not access the data from CS – the The rite of gratuitous hospitality provided by local biggest hospex service. CS became a for-profit corporation in residents to strangers is common among almost all known 2011 and shut down the access of public science to its data. human cultures, especially traditional ones. We can cite Scientists possessing pre-incorporation CS data are prohibited melmastia of Pashtun [1, p. 14], terranga of Wolof [2, p. to share it with third parties. HC never allowed access of 17] and hospitality of Eskimo [3] as examples of traditional public science to its data. -

Meet Your Strawman

Meet Your Strawman This is a picture of "The Houses of Parliament" in London, England. Let's have a little quiz: 1. Who meets there? 2. What do they do there? 3. Do they help you in any way? If your answers were: 1. "Members of the government" 2. "They represent all the people living in the country" and 3. "Yes, they create laws to protect me and my family. Then let me congratulate you on getting every one of the answers wrong. Didn't do too well on that quiz? OK, let's have another go: 4. When was slavery abolished? 5. Was slavery legal? 6. Are you in debt to a financial institution? Here are the answers: 1. The serving officers of a commercial company. 2. They think up ways to take money and goods from you. 3. No, absolutely not, they help themselves and not you. 4. Slavery has NEVER been abolished and you yourself, are considered to be a slave right now. 5. Yes, slavery is "legal" although it is not "lawful" (you need to discover the difference). 6. No. You are NOT in debt to any financial institution. 1 Does this seem a little strange to you? If it does, then read on: THOSE IN POWER HAVE A BIG SECRET Paying tax is OPTIONAL !! Registering a vehicle is OPTIONAL !! Paying a fine is OPTIONAL !! Attending a court is OPTIONAL !! YOU CAN IF YOU WANT TO, BUT YOU DON’T HAVE TO Surprised? Well – try this for size: Every Mortgage and Loan is FULLY REPAID from day one – you can pay it again if you want to, but you don’t have to !! If nobody nobody has told that you that you have a Strawman, then this could be a very interesting experience for you. -

Bakalářská Práce

VYSOKÁ ŠKOLA POLYTECHNICKÁ JIHLAVA CESTOVNÍ RUCH BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE Kateřina Klacková 2016 Couchsurfing versus konkurenční sítě Originální list zadání BP Prohlašuji, že předložená bakalářská práce je původní a zpracoval/a jsem ji samostatně. Prohlašuji, že citace použitých pramenů je úplná, že jsem v práci neporušil/a autorská práva (ve smyslu zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů, v platném znění, dále též „AZ“). Souhlasím s umístěním bakalářské práce v knihovně VŠPJ a s jejím užitím k výuce nebo k vlastní vnitřní potřebě VŠPJ. Byl/a jsem seznámen/a s tím, že na mou bakalářskou práci se plně vztahuje AZ, zejména § 60 (školní dílo). Beru na vědomí, že VŠPJ má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití mé bakalářské práce a prohlašuji, že souhlasím s případným užitím mé bakalářské práce (prodej, zapůjčení apod.). Jsem si vědom/a toho, že užít své bakalářské práce či poskytnout licenci k jejímu využití mohu jen se souhlasem VŠPJ, která má právo ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, vynaložených vysokou školou na vytvoření díla (až do jejich skutečné výše), z výdělku dosaženého v souvislosti s užitím díla či poskytnutím licence. V Jihlavě dne 15. dubna 2016 ………………………………… podpis Ráda bych tímto poděkovala Mgr. Martině Černé, Ph.D., která se ujala vedení mé práce. Velice jí děkuji za její ochotu, trpělivost, cenné rady a připomínky, které mi poskytla během řešení bakalářské práce. Velké díky také patří mé rodině a partnerovi za morální podporu nejen při psaní bakalářské práce, ale i po dobu celého studia. VYSOKÁ ŠKOLA POLYTECHNICKÁ JIHLAVA Katedra cestovního ruchu Couchsurfing versus konkurenční sítě Bakalářská práce Autor: Kateřina Klacková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. -

Ridingwithstrangersmaikemewe

Riding with Strangers: An Ethnographic Inquiry into Contemporary Practices of European Hitchhikers Wissenschaftliche Hausarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Master of Arts der Universität Hamburg von Maike Mewes aus Hamburg Hamburg, 2016 I inhale great draughts of space, the East and the West are mine, and the North and the South are mine. Walt Whitman Song of the Open Road, 1856 Dedicated to all hitchhikers i Acknowledgements I wish to thank all those who have supported me in the process of writing this work, through their encouragement, advice, time, and companionship. Prof. Sabine Kienitz, for her enduring support, open mind, and unwavering patience in the prolonged supervision that this work required. The many hitchhikers, who shared their views and wine and journeys with me, allowed me insights into their lives and thoughts, and patiently tolerated my inquisitiveness. My parents, for everything. I could write another 100 pages about how you have sup- ported me. Thank you. My siblings, for keeping my spirits up and my feet on the ground. My grandmother, for tea and talk. And Annette, for always being there for me. Jana, for going through the entire process with me, side by side each step of the way, sharing every eye-roll, whine, and plan doomed to fail. Dominic, who endured us both, and never tired of giving his insightful advice, of making us laugh and of making us food. I could not have done it without you. All friends, for supporting and distracting me. And all the drivers who gave me a ride. ii Table of Contents 1. -

Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta the Law Courts A1 Sir Winston Churchill Square Edmonton Alberta T5J-0R2

Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta Citation: AVI v MHVB, 2020 ABQB 489 Date: 20200826 Docket: FL03 55142 Registry: Edmonton Between: AVI Applicant and MHVB Respondent and Jacqueline Robinson, a.k.a. Jacquie Phoenix Third Party and Unauthorized Alleged Representative _______________________________________________________ Memorandum of Decision of the Honourable Mr. Justice Robert A. Graesser _______________________________________________________ I. Introduction [1] Pseudolaw is a collection of spurious legally incorrect ideas that superficially sound like law, and purport to be real law. In layman’s terms, pseudolaw is pure nonsense. [2] Pseudolaw is typically employed by conspiratorial, fringe, criminal, and dissident minorities who claim pseudolaw replaces or displaces conventional law. These groups attempt to Page: 2 gain advantage, authority, and other benefits via this false law. In Meads v Meads, 2012 ABQB 571 [Meads], Associate Chief Justice Rooke reviewed many forms of and variations on pseudolaw that have been deployed in Canada. In his decision, he described populations and personalities that use these ideas, and explained how these “Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Argument” [“OPCA”] concepts are legally false and universally rejected by Canadian courts. Rooke ACJ concluded OPCA strategies are instead scams promoted to gullible, ill-informed, and often greedy individuals by unscrupulous “guru” personalities. Employing pseudolaw is always an abuse of court processes, and warrants immediate court response: Unrau v National Dental Examining Board, 2019 ABQB 283 at paras 180, 670-671 [Unrau #2]. [3] To date Canada has weathered two waves of pseudolaw. In the 2000 “Detaxers” held seminars and taught classes on how to supposedly avoid paying income tax, for example by claiming that ROBERT GRAESSER is a legal person and a taxpayer, while Robert-A.: Graesser is a physical human being and therefore exempt from tax: Meads at paras 87-98. -

Couchsurfing-Iskustva Ugošćavanja

Couchsurfing-iskustva ugošćavanja Galić, Viktorija Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2017 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Department of Croatian Studies / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Hrvatski studiji Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:111:378377 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of University of Zagreb, Centre for Croatian Studies SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU HRVATSKI STUDIJI ODJEL ZA SOCIOLOGIJU Viktorija Galić CouchSurfing – iskustva ugošćavanja ZAVRŠNI RAD Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Renato Matić Zagreb, 2017. Sadržaj Sažetak 1. Uvod ....................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Opis istraživanja ..................................................................................................................... 5 3. Pitanja u istraživanju .............................................................................................................. 6 3.1 Zašto ste se odlučili ugošćavati preko CouchSurfinga? ................................................... 6 3.2 Što Vam se sviđa kod ugošćavanja? ................................................................................ 8 3.3 Što Vam se ne sviđa ili predstavlja problem kod ugošćavanja? ...................................... 9 3.4 Imate li neka pravila ili ograničenja koja primjenjujete kod prihvaćanja članova kod ugošćavanja? -

Autumn 2K6 Publisher 06G Spare

Total Liberty A journal of Evolutionary Anarchism Volume 5 Number 3 AutuAutumnmn / Winter 2006 £1.00 Radicals held a conference this year in Leeds at- tended by one of Total Liberty’s regular writers. His CONTENTS comments as to the main difference between this and other secular anarchist gatherings were “I was warmly greeted as a stranger, the ratio of women and men was fairly even, the talks and workshops started and Editorial ............................................................. Page 2 finished on time, there was a greater emphasis on The Critics of Clone Towns listening than speaking. It was all very refreshing. I came away quite liking these people. Most choose to By Nigel Meek ................................................... Page 3 live a very simple life; they are as anti-hierarchical Three Examples of Free Association and anti-state as the rest of us. A lot of ideas floating By Steve Cullen ................................................ Page 4 around and a pronounced absence of dogma. It brought home to me the importance of tolerance and A Rebirth of Anarchism? integrity needed in a free community.” by Larry Gambone ............................................ Page 6 “Do the small things” is a saying attributed to Saint The strange case of Kropotkin’s chair, David, a 6th century religious figure from Wales, but it Clement Attlee’s pipe and a Brighton omnibus is as valid today for non-religious individuals, small groups and also for anarchist politics. To welcome by Chris Draper.................................................. Page 8 new comrades, to listen to others, to be open to new Can there be such a thing as a Christian Anarchist? ideas and interpretations, these are vital if anarchists are to keep in touch with being human, and also if the By Keith Hebden .............................................. -

A Rebellion of Furious Paper: Pseudolaw As a Revolutionary Legal System Donald J

A Rebellion of Furious Paper: Pseudolaw as a Revolutionary Legal System Donald J. Netolitzky1 Paper delivered at the Centre d’expertise et de formation sur les intégrismes religieux et la radicalisation (CEFIR) symposium: “Sovereign Citizens in Canada”, Montreal, 3 May 2018 Abstract Pseudolaw is a collection of legal-sounding but false rules that purport to be law. Though pseudolaw is now encountered by courts and government actors in many countries world-wide, pseudolaw is remarkably constant, nation-to-nation. This observation is explained by the crystallization circa 1999-2000 of a matrix of pseudolaw concepts interwoven with a conspiratorial anti- government narrative. This Pseudolaw Memeplex was incubated in the US Sovereign Citizen community. The Memeplex then spread internationally and into additional anti-government communities. That expansion either complemented or replaced other pre-existing pseudolaw systems. The Sovereign Citizen Pseudolaw Memeplex has six core concepts: 1) everything is a contract, 2) silence means agreement, 3) legal action requires an injured party, 4) government authority is defective or limited, 5) the “Strawman” duality, and 6) monetary and banking conspiracy theories. Only the defective government authority component shows significant national- and community-based variation. This adaptation is necessary for the Memeplex to plausibly operate with a new non-Sovereign Citizen host population. The “Strawman” duality is second-order pseudolaw, in that the 1 Donald J. Netolitzky (Ph.D. Microbiology, University of Alberta, 1995, LL.B., University of Alberta, 2005) is the Complex Litigant Management Counsel for the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author, and not those of any other member of the Court of Queen’s Bench, or the Court itself. -

Interfaces of Location and Memory: an Exploration of Place Through Context-Led Arts Practice

Title Interfaces of location and memory: An exploration of place through context-led arts practice. Type Thesis URL http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/7764/ Date 2011 Citation Lovejoy, Annie (2011) Interfaces of location and memory: An exploration of place through context-led arts practice. PhD thesis, University of the Arts London and Falmouth University. Creators Lovejoy, Annie Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Interfaces of location and memory An exploration of place through context-led arts practice. Annie Lovejoy Falmouth University A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University of the Arts London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy __________ August 2011 Interfaces of location and memory An exploration of place through context-led arts practice TEXT Abstract Interfaces of location and memory is a conceptual framework that invites an understanding of context-led arts practice that is responsive to the particularities of place, rather than a model of practice that is applied to a place.! ‘Socially engaged’ and ‘relational’ practice are examples of contemporary arts field designations that suggest a modus operandi – an operative arts strategy. The presence of such concepts form the necessary conditions for investment in public art sector projects, biennales, community outreach and regeneration programmes. The problem here is that the role of the artist/artwork can be seen as promising to be transformational, but in reality this implied promise can compromise artistic integrity and foreclose a work’s potential. -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. COUNTERING THE TERRORIST THREAT IN CANADA: AN INTERIM REPORT Standing Senate Committee on National Security and Defence The Honourable Daniel Lang Chair The Honourable Grant Mitchell Deputy -

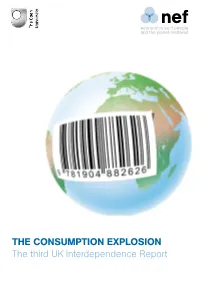

THE CONSUMPTION EXPLOSION the Third UK Interdependence Report the UK’S Global Ecological Footprint

THE CONSUMPTION EXPLOSION The third UK Interdependence Report The UK’s global ecological footprint The United Kingdom consumes products from around the world creating a large ecological footprint. The footprint measures natural resources by the amount of land area required to provide them. This map shows fl ow lines for imported resources that make up our footprint. To attribute impacts properly to the UK consumer, the area required to produce imported goods – a standardised measure of resource use called ‘global hectares’ (gha) – is subtracted from the footprint of the producing countries and is added to the UK’s account. This map is based on data for the total footprint of imports, and summed across product categories. NB: Europe as a source of products is shown disproportionately large because adjustments are not made for re-exports due to the complications of tracing certain goods. This may create a bias suggesting that more raw resources come from European ports when in fact it was merely their most recent port of call on their way from their original source. Our way of life in the UK would be unthinkable without the human, cultural, economic and environmental contributions made by the rest of the world. Our global interdependence is inescapable. But it can also be troubling. The burden in terms of resource consumption that our lifestyles exert on the fields, forests, rivers, seas and mines of the rest of the world is increasing. Months tick by to the point when it becomes much harder to avert runaway climate change. In spite of the global economic downturn, during a typical calendar year, the world as a whole now still goes into ecological debt on 25 September.