Inputs, Monitoring, and Crowd-Out in India's School-Based Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Date 2/ZZ20 7

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF DISTRICT MEDICAL&PUBLIC HEALTH OFFICER, KEONJHAR (NPCB KEONJHAR) Letter No. 723 /DPHO/NPCB/ Keonjhargarh/2021 Date / To The All Superintendent SDHs/ CHCSs, Keonjhar SUNETRA Programme Sub Micro plan of Mobile Vision Centre under Sir, Vision a Mobile herewith the micro plan I am submitting reference to the subject cited above, are With Annexure. Therefore you 2021 as per for the month of Aug Centre under SUNETRA programme jurisdiction to accompany and ASHA under your Assistants, MO Ayush requested to instruct the Ophthnic of the programme. for smooth management the Mobile Vision Centre facility action. information and necessary This is for your kind Yours faithfuly, Enclose-Annexure & Chief District Medical Public Health Officer, Keonjhar Date 2S /2o2 DPH0/NPCB/ Keonjhargarh/2021 Memo No.31 & necessary guidance. concerned for information Copy to person Medical & Chief District Health Officer, Keonjhar Public Date2 12°2/ Memo No.3409/DPHO/NPCB/Keonjhargarh/2021 he is for information & Sakunlala Saho0, Keonjhar forwarded to the M/S Copy positively. vehicle as per Micro plan requested to spare & Chief District Medical Public Heath Officer, Keonjhar Date 2S//29 7/ Memo No3106/DPHO/NPCB/ Keonjhargarh/2021 to information & requested Keonjhar for kind forwaded to the DIO, NIC, Aug-2021 Copy under SUNETRA Programme Mobile Vision Centre the Micro plan of enclosed 02 pages. publish details of the plan are information of citizen. The Keonjhar for Chief District Medical1& Public Health Officer, Keonjhar Date2/ZZ20 7 Memo No.3407/DPHO/NPCB/ Keonjhargarh/2021 kind information Odisha for favour of the CEO,SUNETRA( UEHP), Copy submitted to and necessary action. -

Gover Rnme Nt of Odish Ha

Government of Odisha OUTCOME BUDGET 2013-14 Rural Development Department Hon’ble Chief Minister Odisha taking review of departmental activities of DoRD on 1st March 2013 ………………………….Outcome budget of 2012-13 Sl. Page No. No. CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I-VII 2. 1-16 CHAPTER-I Introduction Outcome Budget, 2013-14 3. 17-109 CHAPTER-II Statement (Plan & Non-Plan) 4. Reform Measures & 110 -112 CHAPTER-III Policy Initiatives 5. Past performance of 113-119 CHAPTER-IV programmes and schemes 6. 120-126 CHAPTER- V Financial Review 7. Gender and SC/ST 127 CHAPTER-VI Budgeting EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Outcome Budget of Department of Rural Development (DoRD) broadly indicates physical dimensions of the financial outlays reflecting the expected intermediate output. The Outcome budget will be a tool to monitor not just the immediate physical "outputs" that are more readily measurable but also the "outcomes" which are the end objectives. 2. The Outcome Budget 2013-14 broadly consists of the following chapters: • Chapter-I:Brief introduction of the functions, organizational set up, list of major programmes/schemes implemented by the Department, its mandate, goals and policy frame work. • Chapter-II:Tabular format(s)/statements indicating the details of financial outlays, projected physical outputs and projected outcomes for 2013-14 under Plan and Non-Plan. • Chapter-III:The details of reform measures and policy initiatives taken by the Department during the course of the year. • Chapter-IV:Write-up on the past performance for the year 2011-12 and 2012-13 (up to December, 2012). • Chapter-V:Actual of the year preceding the previous year, Budget Estimates and Revised Estimates of the previous year, Budget Estimates of the Current Financial year. -

Village and Town Directory, Kendujhar, Part-A, Series-19, Orissa

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1991 SERIES -19 ORISSA PART - XII DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART A -VILLAGE.. AND TOWN DIRECTORY KENDUJHAR R.N. SENAPATI OFTHE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Director of Census Operations, Orissa CENSUS OF INDIA, 1991 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART A - VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY KENDUJHAR FOREWORD Publication of the District Census Handbocks (DCHs )was initiated after the 1951 Census and is continuing since then with some innovations/modifications after each decennial Census. This is the most valuable district level publication brought out by the Census Organisation on behalf of each State Govt./Union Territory administration. It inter-alia provides data/information on some of the basic demographic and socia-economic characteristics and on the availability of certain important civic amenities/facilities in each village and town of the respective districts. This publication has thus proved to be of immense utility to the planners, administrators, academicians and researchers. The scope of the DCH was initially confined to certain important census tables on population, economic and socia-cultural aspects as also the Primary Census Abstract (PCA) of each village and town (ward-wise) of the district. The DCHs published after the 1961 Census contained a descriptive account of the district administrative statistics, census tables and Village and Town Directories including PCA. After the1971 Census,two parts of the District Census Handbooks (Part-A comprising Village and Town Directories and Part -B comprising Village and Town PCA) were released in all the States and Union Territories. The third Part (Part-C) of the District Census Handbooks comprising administrative statistics and district census tables, which was also to be brought out, could not be published in many States/UTs due to considerable delay in compilation of relevant material. -

KEONJHARGARH BLOCK. the Name of the Block Is Keonjhargarh Block

KEONJHARGARH BLOCK. The name of the Block is Keonjhargarh Block. It started functioning in the year 1955. The geographical area of this Block is 297 Sqr. Miles. The population as per 2011 census of this Block is 162148 out of which Male Population is 81305, Female Population is 80843, ST Population is 81567SC Population is 16082 and Others are 64499 no. The literate population of this Block is 94723. Category wise the population percentage of this Block is as follows, Male:- 50.14, Female :- 49.86, ST :- 50.3, SC : 09.9, Oth :- 39.8 and literate population percentage is 58.4. The total Households of this Block is 35963 no. This Block consists of 24 no. of GPs in which there are 231 Revenue villages and 09 hamlets. The Block has 01 no. of CHC , 05 no. of New PHC, 02 no. of Govt. Homeopathy Dispensary, 30 no. of ANM centers, 190 Asha centers, 261 no. of AW centers, 198 no. of GKS for facilitation of better health care of the villagers. For education regards the Block has 141 no. of PS, 25 no. of PUPS, 11 no. of NUPS, 21 no. of UPS, 17 no. of UGMES, 38 no. of High Schools, 03 no. of Degree Colleges and 02 no. of Degree Engineering Colleges. The Block provides drinking water to the inhabitants through 1584 no. of Tube Wells, 47 Wells and 25 no. of Piped Water System. To irrigate its agricultural fields the Block has 03 MIPs. 36 no. of Financial Institutions and 02 no. of LAMPS are functioning in the Block and they are financing the villagers in respect of ISB, Agriculture, Pisciculture and all sort of segments including credit linkage to SHG groups. -

Ground Water Year Book 2016-2017

Government of India CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD Ministry of Water Resources & Ganga Rejuvenation GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK 2016-2017 South Eastern Region Bhubaneswar September 2017 F O R E W O R D Groundwater is a major natural replenishable resource to meet the water requirement for irrigation, domestic and industrial needs. It plays a key role in the agrarian economy of the state. Though richly endowed with various natural resources, the state of Orissa has a long way to go before it can call itself developed. Being heavily dependent on rain fed agriculture; the state is very often exposed to vagaries of monsoon like flood and drought. The importance of groundwater in mitigating the intermittent drought condition of a rain-fed economy cannot be overemphasized. To monitor the effect caused by indiscriminate use of this precious resource on groundwater regime, Central Ground Water Board, South Eastern Region, Bhubaneswar has established about 1606 National Hydrograph Network Stations (NHNS) (open / dug wells) and 89 purpose built piezometres under Hydrology Project in the state of Orissa. The water levels are being monitored four times a year. Besides, to study the change in chemical quality of groundwater in time and space, the water samples from these NHNS are being collected once a year (Pre-monsoon) and analysed in the Water Quality Laboratory of the Region. The data of both water level and chemical analysis are being stored in computers using industry standard Relational Database Management System (RDBMS) like Oracle and MS SQL Server. This is very essential for easy retrieval and long-term sustainability of data. -

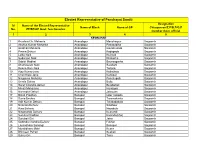

Elected Representative of Panchayat Samiti Designation Sl Name of the Elected Representative Name of Block Name of GP Chiarperson/Z.P/B.P/G.P No

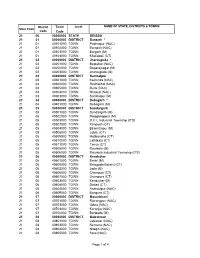

Elected Representative of Panchayat Samiti Designation Sl Name of the Elected Representative Name of Block Name of GP Chiarperson/Z.P/B.P/G.P No. ZP/BP/GP Govt. functionaries member Govt. official 1 2 3 4 5 KEONJHAR 1 Krushna Ch. Mohanta Anandapur Manoharpur Sarpanch 2 Akshya Kumar Mohanta Anandapur Panasadiha Sarpanch 3 Giridhari Mohanta Anandapur Gayalmunda Sarpanch 4 Prema Dehuri Anandapur Kodapada Sarpanch 5 Lalita Naik Anandapur Kolimati Sarpanch 6 Sudarsan Naik Anandapur Dhakotha Sarpanch 7 Sabitri Madhei Anandapur Baunsagarha Sarpanch 8 Ghanasyam Naik Anandapur Salabani Sarpanch 9 Reena Rani Naik Anandapur Tartara Sarpanch 10 Ajay Kumar jena Anandapur Kathakata Sarpanch 11 Chanchala Jena Anandapur Kantipal Sarpanch 12 Nirupama Mohanty Anandapur Panchupalli Sarpanch 13 Urmila Sahoo Anandapur Bailo Sarpanch 14 Sarat Chandra dehuri Anandapur Belabahali Sarpanch 15 Minati Moharana Anandapur Haridapal Sarpanch 16 Narendra Dehuri Anandapur Jalasuan Sarpanch 17 Binati Pradhan Banspal Uper raigoda Sarpanch 18 Sunia Beshra Banspal Taramakanta Sarpanch 19 Adit Kumar Dehury Banspal Talakadakala Sarpanch 20 Niranjan Dehury Banspal Singhpur Sarpanch 21 Rina Behera Banspal Nayakote Sarpanch 22 Nityananda Dehury Banspal Kumundi Sarpanch 23 Sumitra Pradhan Banspal Kalanda(kha) Sarpanch 24 Surubali Giri Banspal Jatra Sarpanch 25 Gobinda chandra Dehury Banspal Fuljhar Sarpanch 26 Laxmidhara Sanangi Banspal Banspal Sarpanch 27 Muralidhara Matri Banspal Kuanr Sarpanch 28 Bhimsen Puhan Banspal Suakati Sarpanch 29 Sukru Giri Banspal Tana Sarpanch Elected -

Keonjhar Dairy

OMFED RETAILERS COMPENSATION SCHEME KEONJHAR DAIRY (01.04.2003 TO 31.03.2012) Name of Retailer Amount (Rs) Abhiram Sahoo 5471.06 Ajay Ku Ray,Karanjia 8873.77 A.K.Dash,Padana Chhak,Anandpur 9191.64 Akshya Ku Giri,Ukhunda 1458.15 Anand Ch. Biswal,Bhadrasahi 32833.21 Anand Swain,Ramachandrapur 821.75 A Paul, Badampahar 209.5 Arun Ku Behera,Pipilia 1878.9 Ashok Ku. Ghadei 4983.05 Asis Ku Panigrahi,Karanjia 7194.01 Atish Ku Saha 1908.2 Atish Ku. Sahoo,Jagannathpur Chhak 9640.48 Badal Dutta,Baniapat 6935.95 Balabhadra Mohanta,Msp,Champua 232.75 Barendranath Deobabu,Karanjia 7241.02 Basant Ku. Naik,Bus Stand, Ghatgaon 15507.8 Basudev Das,Janara,Anandapur 1093.8 Bbadal Chandra Dutta,Baniapat 7367.08 Bhagabat Sahoo,NH-6,Turumunga 16702.39 Bharat Babulal Thakkar,Bustand,Barbil 92221.41 Bibekananda Prusty, Gate Parlour 856.5 Bijaya Ku. Panda 7103.98 Bijay Ku Mohanta, Karanjia 10504.95 Bijay Ku. Muduli,Kacheri Chhak,Anandpur 13266.98 Bijay Ku. Raj,Bus Stand,Champua 27633.06 Bijay Ku Ray,Neaer SBI, Karanjia 5859.85 Bikash Das Adhikari,Patakat Chhak,Karanjia 3596.25 Binod Ray 59726.11 Biswanath Barik, Kjr 7536.45 B.K.Mohakud 8707.9 Braja Kishore Behera,Raisuan 5183.6 Braja Mohan Jena,Rly. Station 83.5 B.R. Mishra,Rimuli Taxi Stand 5586.15 B R Sahoo,Keonjhar 9366.16 B Sahoo,Near Municipality Ofc,Kjr 2065.32 B Tripathy, Anandpur 386.05 Chandradev Ray,Radha Krishna Mandir,Kalinga Na 30021.31 Chaturbhuja Das,Belbahali 1844.4 Chittaranjan Das,Champua 1164.55 Chittaranjan Das,Sanakarpur 1027.7 Chitta R Behera,Champua 8138.16 Dasarath Sahoo,FMP Chhak,Joda -

Keonjhar.Pdf

LIST OF MAJOR HEALTH INSTITUTIONS S.No BLOCK NAC PLACE HEALTH UNIT NAME 1 Keonjhar Mty DHH Keonjhar DHH ,Keonjhar 2 Anandapur NAC SDH Anandapur SDH ,Anandapur 3 Champua SDH Champua SDH ,Champua 4 Ghasipura Mty AH Barbil AH ,Barbil 5 Hatadihi AH Hadagarh AH ,Hadagarh 6 Hatadihi AH Hatadihi AH ,Hatadihi 7 Jhumpura AH Ukhunda AH ,Ukhunda 8 Patna AH Dumuria AH ,Dumuria 9 Telkoi AH Kaliahata AH ,Kaliahata 10 Telkoi AH Sirigida AH ,Sirigida 11 Banspal CHC Banspal CHC ,Banspal 12 Champua CHC Bhanda CHC ,Bhanda 13 Ghasipura CHC Sainkul CHC ,Sainkul 14 Ghatagaon UGPHC Ghatagaon UGPHC ,Ghatagaon 15 Harichandanpur CHC Harichandanpur CHC ,Harichandanpur 16 Hatadihi CHC Salania CHC ,Salania 17 Jhumpura CHC Jhumpura CHC ,Jhumpura 18 Joda CHC Basudevpur CHC ,Basudevpur 19 Keonjhar CHC Padmapur CHC ,Padmapur 20 Patna CHC Patna CHC ,Patna 21 Telkoi CHC Telkoi CHC ,Telkoi 22 Anandapur PHC Fakirpur PHC ,Fakirpur 23 Ghasipura PHC Kesudurapal PHC ,Kesudurapal 24 Harichandanpur PHC Bhagamunda PHC ,Bhagamunda 25 Saharapada PHC Udayapur PHC ,Udayapur 26 Anandapur NAC PHC(New) Anandapur PHC(New) ,Anandapur 27 Anandapur PHC(New) Panchupalli PHC(New) ,Panchupalli 28 Anandapur PHC(New) Panasadiha PHC(New) ,Panasadiha 29 Anandapur PHC(New) Dhakota PHC(New) ,Dhakota 30 Anandapur PHC(New) Salabani PHC(New) ,Salabani 31 Anandapur PHC(New) Tartara PHC(New) ,Tartara 32 Banspal PHC(New) Phuljhar PHC(New) ,Phuljhar 33 Banspal PHC(New) Gonasika PHC(New) ,Gonasika 34 Banspal PHC(New) Kolanda PHC(New) ,Kolanda 35 Banspal PHC(New) Suakati PHC(New) ,Suakati 36 Champua PHC(New) -

Draft District Survey Report (Dsr) of Keonjhar District, Odisha for Laterite Slab

DRAFT DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT (DSR) OF KEONJHAR DISTRICT, ODISHA FOR LATERITE SLAB (FOR PLANNING & EXPLOITING OF MINOR MINERAL RESOURCES) ODISHA KEONJHAR As per Notification No. S.O. 3611(E) New Delhi, 25th July, 2018 MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE (MoEF & CC) COLLECTORATE, KEONJHAR CONTENT SL NO DESCRIPTION PAGE NO 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 OVERVIEW OF MINING ACTIVITIES IN THE DISTRICT 2 3 GENERAL PROFILE 2 4 GEOLOGY 4 5 DRAINAGE AND IRRIGATION PATTERN 7 6 LANDUSE PATTERN 7 7 SURFACE WATER & GROUND WATER SCENARIO 8 8 RAINFALL & CLIMATIC CONDITION 8 9 DETAILS OF MINING LEASES 8 10 DETAILS OF ROYALTY COLLECTED 8 11 DETAILS OF PRODUCTION 9 12 MINERAL MAP OF THE DISTRICT 9 13 LIST OF LOI HOLDERS ALONG WITH VALIDITY 9 14 TOTAL MINERAL RESERVE AVAILABLE IN THE DISTRICT 9 15 QUALITY/GRADE OF MINERAL 9 16 USE OF MINERAL 9 17 DEMAND & SUPPLY OF THE MINERAL 10 18 MINING LEASES MARKED ON THE MAP OF THE DISTRICT 11 19 DETAILS OF AREAS WHERE THERE IS A CLUSTER OF 12 MINING LEASES 20 DETAILS OF ECO-SENSITIVE AREA 12 21 IMPACT ON THE ENVIRONMENT (AIR, WATER, NOISE, 12 SOIL FLORA & FAUNAL, LAND USE, AGRICULTURE, FOREST ETC.) DUE TO MINING 22 REMEDIAL MEASURES TO MITIGATE THE IMPACT OF 13 MINING ON THE ENVIRONMENT 23 RECLAMATION OF MINED OUT AREA (BEST PRACTICE 15 ALREADY IMPLEMENTED IN THE DISTRICT, REQUIREMENT AS PER RULES AND REGULATION, PROPOSED RECLAMATION PLAN) 24 RISK ASSESSMENT & DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 16 1 | Page 25 DETAILS OF THE OCCUPATION HEALTH ISSUES IN THE 17 DISTRICT. (LAST FIVE- YEAR DATA OF NUMBER OF PATIENTS OF SILICOSIS & TUBERCULOSIS IS ALSO NEEDS TO BE SUBMITTED) 26 PLANTATION OF GREEN BELT DEVELOPMENT IN 18 RESPECT OF LEASES ALREADY GRANTED IN THE DISTRICT 27 ANY OTHER INFORMATION 18 LIST OF PLATES DESCRIPTION PLATE NO INDEX MAP OF THE DISTRICT 1 MAP SHOWING TAHASILS 2 ROAD MAP OF THE DISTRICT 3 MINERAL MAP OF THE DISTRICT 4 LEASE/POTENTIAL AREA MAP OF THE DISTRICT 5 2 | Page PLATE NO- 1 INDEX MAP ODISHA KEONJHAR PLATE NO- 2 MAP SHOWING THE TAHASILS OF KEONJHAR DISTRICT KENDUJHAR , Jharkhand TEHSILMAP / Sundargarh Mayurbhanj .-.....•~"\. -

District Mineral Foundation District Mineral Foundation

INDICATIVE PLAN DISTRICT MINERAL FOUNDATION KEONJHAR, ODISHA Centre for Science and Environment © 2019 Centre for Science and Environment Material from this publication can be used, but with acknowledgement. Published by Centre for Science and Environment 41, Tughlakabad Institutional Area New Delhi 110 062 Phones: 91-11-29955124, 29955125, 29953394 Fax: 91-11-29955879 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cseindia.org INDICATIVE PLAN DISTRICT MINERAL FOUNDATION KEONJHAR, ODISHA Centre for Science and Environment Contents PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ..................................................................................7 SECTION 2: BACKGROUND OF THE DISTRICT ................................................................................10 SECTION 3: SITUATION ANALYSIS THROUGH STOCK-TAKING ..........................................14 SECTION 4: SITUATION ANALYSIS THROUGH PARTICIPATORY RURAL APPRAISAL .............................................................................................................51 SECTION 5: ECONOMIC RESOURCE MAPPING ............................................................................. 59 SECTION 6: PRIORITIZING ISSUES AND APPROACHES FOR INTERVENTION THROUGH AN OUTCOME-OUTPUT FRAMEWORK ............................................. 62 REFERENCES ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Proposal Iron Ore Production to 3 MTPA & Mn Ore Production to 0.05

Project Summary Dubna Sakradihi Iron & Manganese Mine in Barbil and Jhumpura tehsil, Keonjhar district, Odisha of M/s. OMC Proposal Iron ore production to 3 MTPA & Mn ore production to 0.05 MTPA. Location of Mine Barbil and Jhumpura Tehsil in Keonjhar district of Odisha state. Latitude 21048’37.35634” to 21051’52.01868” N Longitude 85022’17.8389” to 85024’26.47792” E Land Use The mine lease area of Dubna Sakradihi Iron & Manganese lease is 1332.019 ha, comprising of 1243.270 ha of forest land and 88.279 ha of non-forest land. Total Mineable Iron: 20.022 million tonnes Reserves(Mt) Mn: 0.837 million tonnes Life of Mine Iron : 5 years & Mn: 14 years (approx.) Method of Fully mechanized opencast mining method with formation of Mining benches by drilling and blasting Deposits Iron Ore: Deposit-1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 and Patch-II Mn Ore: Deposit-1C_1E, 4,5,6B,8 Stripping Ratio, Iron ore: 0.40; Mn Ore: 3.17 (Waste:Ore) (m3 : t) Waste disposal 16.67 Mm3 waste will be generated from iron ore quarries upto conceptual stage. Entire waste (14.67 Mm3) after 2020 shall be backfilled into quarries. 18.68 Mm3 waste will be generated from manganese ore quarries upto conceptual stage. Entire waste (17.96 Mm3) after 2020 shall be backfilled in quarry void. Mineral Iron Ore: Crushing Unit (1 nos.) of 100 TPH & screening Unit Processing (2+1 nos.) of 300 & 100 TPH respectively (10% of ROM); Mn Ore: only manual sizing and shorting Mineral 90% ROM (iron ore) produced from the quarry will be Transport transported by 35t dumpers. -

Town Code Level

District Town Level NAME OF STATE, DISTRICTS & TOWNS State Code Code Code 21 00 00000000 STATE ORISSA 21 01 00000000 DISTRICT Bargarh * 21 01 40101000 TOWN Padmapur (NAC) 21 01 40102000 TOWN Barapali (NAC) 21 01 40103000 TOWN Bargarh (M) 21 01 40104000 TOWN Khaliapali (CT) 21 02 00000000 DISTRICT Jharsuguda * 21 02 40201000 TOWN Belpahar (NAC) 21 02 40202000 TOWN Brajarajnagar (M) 21 02 40203000 TOWN Jharsuguda (M) 21 03 00000000 DISTRICT Sambalpur 21 03 40301000 TOWN Kochinda (NAC) 21 03 40302000 TOWN Redhakhol (NAC) 21 03 40305000 TOWN Burla (NAC) 21 03 40304000 TOWN Hirakud (NAC) 21 03 40303000 TOWN Sambalpur (M) 21 04 00000000 DISTRICT Debagarh * 21 04 40401000 TOWN Debagarh (M) 21 05 00000000 DISTRICT Sundargarh 21 05 40501000 TOWN Sundargarh (M) 21 05 40502000 TOWN Rajagangapur (M) 21 05 40503000 TOWN O.C.L Industrial Township (ITS) 21 05 40507000 TOWN Panposh (CT) 21 05 40504000 TOWN Biramitrapur (M) 21 05 40508000 TOWN Jalda (CT) 21 05 40509000 TOWN Hatibandha (CT) 21 05 40510000 TOWN Lathikata (CT) 21 05 40511000 TOWN Tensa (CT) 21 05 40505000 TOWN Raurkela (M) 21 05 40506000 TOWN Raurkela Industrial Township (ITS) 21 06 00000000 DISTRICT Kendujhar 21 06 40601000 TOWN Barbil (M) 21 06 40605000 TOWN Balagoda(Bolani) (CT) 21 06 40602000 TOWN Joda (M) 21 06 40606000 TOWN Champua (CT) 21 06 40607000 TOWN Jhumpura (CT) 21 06 40603000 TOWN Kendujhar (M) 21 06 40608000 TOWN Daitari (CT) 21 06 40604000 TOWN Anandapur (NAC) 21 06 40609000 TOWN Bangura (CT) 21 07 00000000 DISTRICT Mayurbhanj 21 07 40701000 TOWN Rairangpur (NAC) 21 07 40703000