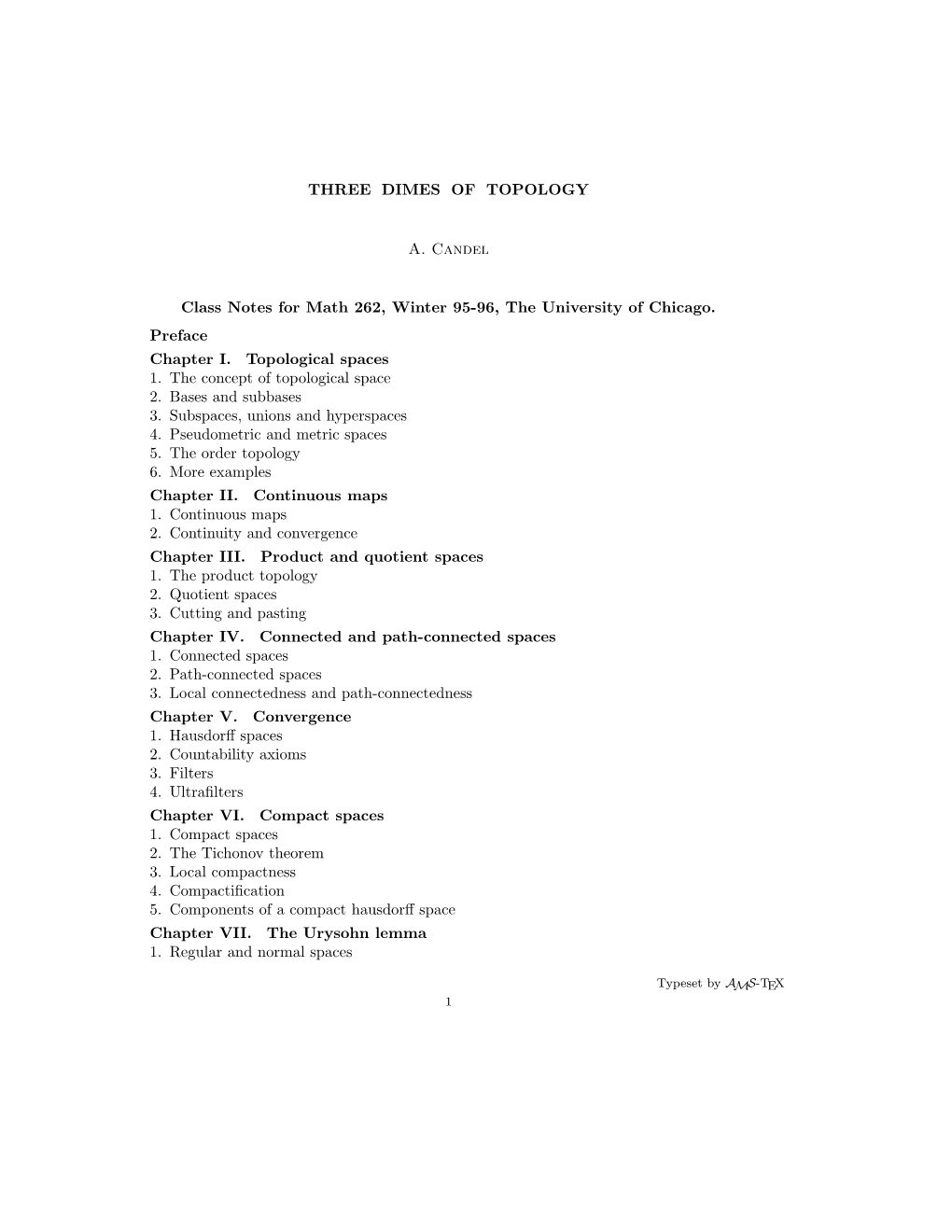

THREE DIMES of TOPOLOGY A. Candel Class Notes for Math 262, Winter 95-96, the University of Chicago. Preface Chapter I. Topologi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to Topology

i i “topguide” — 2010/12/8 — 17:36 — page i — #1 i i A Guide to Topology i i i i i i “topguide” — 2011/2/15 — 16:42 — page ii — #2 i i c 2009 by The Mathematical Association of America (Incorporated) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2009929077 Print Edition ISBN 978-0-88385-346-7 Electronic Edition ISBN 978-0-88385-917-9 Printed in the United States of America Current Printing (last digit): 10987654321 i i i i i i “topguide” — 2010/12/8 — 17:36 — page iii — #3 i i The Dolciani Mathematical Expositions NUMBER FORTY MAA Guides # 4 A Guide to Topology Steven G. Krantz Washington University, St. Louis ® Published and Distributed by The Mathematical Association of America i i i i i i “topguide” — 2010/12/8 — 17:36 — page iv — #4 i i DOLCIANI MATHEMATICAL EXPOSITIONS Committee on Books Paul Zorn, Chair Dolciani Mathematical Expositions Editorial Board Underwood Dudley, Editor Jeremy S. Case Rosalie A. Dance Tevian Dray Patricia B. Humphrey Virginia E. Knight Mark A. Peterson Jonathan Rogness Thomas Q. Sibley Joe Alyn Stickles i i i i i i “topguide” — 2010/12/8 — 17:36 — page v — #5 i i The DOLCIANI MATHEMATICAL EXPOSITIONS series of the Mathematical Association of America was established through a generous gift to the Association from Mary P. Dolciani, Professor of Mathematics at Hunter College of the City Uni- versity of New York. In making the gift, Professor Dolciani, herself an exceptionally talented and successfulexpositor of mathematics, had the purpose of furthering the ideal of excellence in mathematical exposition. -

Open 3-Manifolds Which Are Simply Connected at Infinity

OPEN 3-MANIFOLDS WHICH ARE SIMPLY CONNECTED AT INFINITY C H. EDWARDS, JR.1 A triangulated open manifold M will be called l-connected at infin- ity il each compact subset C of M is contained in a compact poly- hedron P in M such that M—P is connected and simply connected. Stallings has shown that, if M is a contractible open combinatorial manifold which is l-connected at infinity and is of dimension ra^5, then M is piecewise-linearly homeomorphic to Euclidean re-space E" [5]. Theorem 1. Let M be a contractible open 3-manifold, each of whose compact subsets can be imbedded in £3. If M is l-connected at infinity, then M is homeomorphic to £3. Notice that, in order to prove the 3-dimensional Poincaré conjec- ture, it would suffice to prove Theorem 1 without the hypothesis that each compact subset of M can be imbedded in £3. For, if M is a simply connected closed 3-manifold and p is a point of M, then M —p is a contractible open 3-manifold which is clearly l-connected at infinity. Conversely, if the 3-dimensional Poincaré conjecture were known, then the hypothesis that each compact subset of M can be imbedded in £3 would be unnecessary. All spaces and mappings in this paper are considered in the poly- hedral or piecewise-linear sense, unless otherwise stated. As usual, by an open re-manifold is meant a noncompact connected space triangu- lated by a countable simplicial complex without boundary, such that the link of each vertex is piecewise-linearly homeomorphic to the usual (re—1)-sphere. -

Topology and Data

BULLETIN (New Series) OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 46, Number 2, April 2009, Pages 255–308 S 0273-0979(09)01249-X Article electronically published on January 29, 2009 TOPOLOGY AND DATA GUNNAR CARLSSON 1. Introduction An important feature of modern science and engineering is that data of various kinds is being produced at an unprecedented rate. This is so in part because of new experimental methods, and in part because of the increase in the availability of high powered computing technology. It is also clear that the nature of the data we are obtaining is significantly different. For example, it is now often the case that we are given data in the form of very long vectors, where all but a few of the coordinates turn out to be irrelevant to the questions of interest, and further that we don’t necessarily know which coordinates are the interesting ones. A related fact is that the data is often very high-dimensional, which severely restricts our ability to visualize it. The data obtained is also often much noisier than in the past and has more missing information (missing data). This is particularly so in the case of biological data, particularly high throughput data from microarray or other sources. Our ability to analyze this data, both in terms of quantity and the nature of the data, is clearly not keeping pace with the data being produced. In this paper, we will discuss how geometry and topology can be applied to make useful contributions to the analysis of various kinds of data. -

The Long Line

The Long Line Richard Koch November 24, 2005 1 Introduction Before this class began, I asked several topologists what I should cover in the first term. Everyone told me the same thing: go as far as the classification of compact surfaces. Having done my duty, I feel free to talk about more general results and give details about one of my favorite examples. We classified all compact connected 2-dimensional manifolds. You may wonder about the corresponding classification in other dimensions. It is fairly easy to prove that the only compact connected 1-dimensional manifold is the circle S1; the book sketches a proof of this and I have nothing to add. In dimension greater than or equal to four, it has been proved that a complete classification is impossible (although there are many interesting theorems about such manifolds). The idea of the proof is interesting: for each finite presentation of a group by generators and re- lations, one can construct a compact connected 4-manifold with that group as fundamental group. Logicians have proved that the word problem for finitely presented groups cannot be solved. That is, if I describe a group G by giving a finite number of generators and a finite number of relations, and I describe a second group H similarly, it is not possible to find an algorithm which will determine in all cases whether G and H are isomorphic. A complete classification of 4-manifolds, however, would give such an algorithm. As for the theory of compact connected three dimensional manifolds, this is a very ex- citing time to be alive if you are interested in that theory. -

One Dimensional Locally Connected S-Spaces

One Dimensional Locally Connected S-spaces ∗ Joan E. Hart† and Kenneth Kunen‡§ October 28, 2018 Abstract We construct, assuming Jensen’s principle ♦, a one-dimensional locally connected hereditarily separable continuum without convergent sequences. 1 Introduction All topologies discussed in this paper are assumed to be Hausdorff. A continuum is any compact connected space. A nontrivial convergent sequence is a convergent ω–sequence of distinct points. As usual, dim(X) is the covering dimension of X; for details, see Engelking [5]. “HS” abbreviates “hereditarily separable”. We shall prove: Theorem 1.1 Assuming ♦, there is a locally connected HS continuum Z such that dim(Z)=1 and Z has no nontrivial convergent sequences. Note that points in Z must have uncountable character, so that Z is not heredi- tarily Lindel¨of; thus, Z is an S-space. arXiv:0710.1085v1 [math.GN] 4 Oct 2007 Spaces with some of these features are well-known from the literature. A compact F-space has no nontrivial convergent sequences. Such a space can be a continuum; for example, the Cechˇ remainder β[0, 1)\[0, 1) is connected, although not locally con- nected; more generally, no infinite compact F-space can be either locally connected or HS. In [13], van Mill constructs, under the Continuum Hypothesis, a locally con- nected continuum with no nontrivial convergent sequences. Van Mill’s example, ∗2000 Mathematics Subject Classification: Primary 54D05, 54D65. Key Words and Phrases: one-dimensional, Peano continuum, locally connected, convergent sequence, Menger curve, S-space. †University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh, WI 54901, U.S.A., [email protected] ‡University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A., [email protected] §Both authors partially supported by NSF Grant DMS-0456653. -

Topological Description of Riemannian Foliations with Dense Leaves

TOPOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION OF RIEMANNIAN FOLIATIONS WITH DENSE LEAVES J. A. AL¶ VAREZ LOPEZ*¶ AND A. CANDELy Contents Introduction 1 1. Local groups and local actions 2 2. Equicontinuous pseudogroups 5 3. Riemannian pseudogroups 9 4. Equicontinuous pseudogroups and Hilbert's 5th problem 10 5. A description of transitive, compactly generated, strongly equicontinuous and quasi-e®ective pseudogroups 14 6. Quasi-analyticity of pseudogroups 15 References 16 Introduction Riemannian foliations occupy an important place in geometry. An excellent survey is A. Haefliger’s Bourbaki seminar [6], and the book of P. Molino [13] is the standard reference for riemannian foliations. In one of the appendices to this book, E. Ghys proposes the problem of developing a theory of equicontinuous foliated spaces parallel- ing that of riemannian foliations; he uses the suggestive term \qualitative riemannian foliations" for such foliated spaces. In our previous paper [1], we discussed the structure of equicontinuous foliated spaces and, more generally, of equicontinuous pseudogroups of local homeomorphisms of topological spaces. This concept was di±cult to develop because of the nature of pseudogroups and the failure of having an in¯nitesimal characterization of local isome- tries, as one does have in the riemannian case. These di±culties give rise to two versions of equicontinuity: a weaker version seems to be more natural, but a stronger version is more useful to generalize topological properties of riemannian foliations. Another relevant property for this purpose is quasi-e®ectiveness, which is a generalization to pseudogroups of e®ectiveness for group actions. In the case of locally connected fo- liated spaces, quasi-e®ectiveness is equivalent to the quasi-analyticity introduced by Date: July 19, 2002. -

Chapter 7 Separation Properties

Chapter VII Separation Axioms 1. Introduction “Separation” refers here to whether or not objects like points or disjoint closed sets can be enclosed in disjoint open sets; “separation properties” have nothing to do with the idea of “separated sets” that appeared in our discussion of connectedness in Chapter 5 in spite of the similarity of terminology.. We have already met some simple separation properties of spaces: the XßX!"and X # (Hausdorff) properties. In this chapter, we look at these and others in more depth. As “more separation” is added to spaces, they generally become nicer and nicer especially when “separation” is combined with other properties. For example, we will see that “enough separation” and “a nice base” guarantees that a space is metrizable. “Separation axioms” translates the German term Trennungsaxiome used in the older literature. Therefore the standard separation axioms were historically named XXXX!"#$, , , , and X %, each stronger than its predecessors in the list. Once these were common terminology, another separation axiom was discovered to be useful and “interpolated” into the list: XÞ"" It turns out that the X spaces (also called $$## Tychonoff spaces) are an extremely well-behaved class of spaces with some very nice properties. 2. The Basics Definition 2.1 A topological space \ is called a 1) X! space if, whenever BÁC−\, there either exists an open set Y with B−Y, CÂY or there exists an open set ZC−ZBÂZwith , 2) X" space if, whenever BÁC−\, there exists an open set Ywith B−YßCÂZ and there exists an open set ZBÂYßC−Zwith 3) XBÁC−\Y# space (or, Hausdorff space) if, whenever , there exist disjoint open sets and Z\ in such that B−YC−Z and . -

Lecture 13: Basis for a Topology

Lecture 13: Basis for a Topology 1 Basis for a Topology Lemma 1.1. Let (X; T) be a topological space. Suppose that C is a collection of open sets of X such that for each open set U of X and each x in U, there is an element C 2 C such that x 2 C ⊂ U. Then C is the basis for the topology of X. Proof. In order to show that C is a basis, need to show that C satisfies the two properties of basis. To show the first property, let x be an element of the open set X. Now, since X is open, then, by hypothesis there exists an element C of C such that x 2 C ⊂ X. Thus C satisfies the first property of basis. To show the second property of basis, let x 2 X and C1;C2 be open sets in C such that x 2 C1 and x 2 C2. This implies that C1 \ C2 is also an open set in C and x 2 C1 \ C2. Then, by hypothesis, there exists an open set C3 2 C such that x 2 C3 ⊂ C1 \ C2. Thus, C satisfies the second property of basis too and hence, is indeed a basis for the topology on X. On many occasions it is much easier to show results about a topological space by arguing in terms of its basis. For example, to determine whether one topology is finer than the other, it is easier to compare the two topologies in terms of their bases. -

General Topology

General Topology Tom Leinster 2014{15 Contents A Topological spaces2 A1 Review of metric spaces.......................2 A2 The definition of topological space.................8 A3 Metrics versus topologies....................... 13 A4 Continuous maps........................... 17 A5 When are two spaces homeomorphic?................ 22 A6 Topological properties........................ 26 A7 Bases................................. 28 A8 Closure and interior......................... 31 A9 Subspaces (new spaces from old, 1)................. 35 A10 Products (new spaces from old, 2)................. 39 A11 Quotients (new spaces from old, 3)................. 43 A12 Review of ChapterA......................... 48 B Compactness 51 B1 The definition of compactness.................... 51 B2 Closed bounded intervals are compact............... 55 B3 Compactness and subspaces..................... 56 B4 Compactness and products..................... 58 B5 The compact subsets of Rn ..................... 59 B6 Compactness and quotients (and images)............. 61 B7 Compact metric spaces........................ 64 C Connectedness 68 C1 The definition of connectedness................... 68 C2 Connected subsets of the real line.................. 72 C3 Path-connectedness.......................... 76 C4 Connected-components and path-components........... 80 1 Chapter A Topological spaces A1 Review of metric spaces For the lecture of Thursday, 18 September 2014 Almost everything in this section should have been covered in Honours Analysis, with the possible exception of some of the examples. For that reason, this lecture is longer than usual. Definition A1.1 Let X be a set. A metric on X is a function d: X × X ! [0; 1) with the following three properties: • d(x; y) = 0 () x = y, for x; y 2 X; • d(x; y) + d(y; z) ≥ d(x; z) for all x; y; z 2 X (triangle inequality); • d(x; y) = d(y; x) for all x; y 2 X (symmetry). -

Advance Topics in Topology - Point-Set

ADVANCE TOPICS IN TOPOLOGY - POINT-SET NOTES COMPILED BY KATO LA 19 January 2012 Background Intervals: pa; bq “ tx P R | a ă x ă bu ÓÓ , / / calc. notation set theory notation / / \Open" intervals / pa; 8q ./ / / p´8; bq / / / -/ ra; bs; ra; 8q: Closed pa; bs; ra; bq: Half-openzHalf-closed Open Sets: Includes all open intervals and union of open intervals. i.e., p0; 1q Y p3; 4q. Definition: A set A of real numbers is open if @ x P A; D an open interval contain- ing x which is a subset of A. Question: Is Q, the set of all rational numbers, an open set of R? 1 1 1 - No. Consider . No interval of the form ´ "; ` " is a subset of . We can 2 2 2 Q 2 ˆ ˙ ask a similar question in R . 2 Is R open in R ?- No, because any disk around any point in R will have points above and below that point of R. Date: Spring 2012. 1 2 NOTES COMPILED BY KATO LA Definition: A set is called closed if its complement is open. In R, p0; 1q is open and p´8; 0s Y r1; 8q is closed. R is open, thus Ø is closed. r0; 1q is not open or closed. In R, the set t0u is closed: its complement is p´8; 0q Y p0; 8q. In 2 R , is tp0; 0qu closed? - Yes. Chapter 2 - Topological Spaces & Continuous Functions Definition:A topology on a set X is a collection T of subsets of X satisfying: (1) Ø;X P T (2) The union of any number of sets in T is again, in the collection (3) The intersection of any finite number of sets in T , is again in T Alternative Definition: ¨ ¨ ¨ is a collection T of subsets of X such that Ø;X P T and T is closed under arbitrary unions and finite intersections. -

Zuoqin Wang Time: March 25, 2021 the QUOTIENT TOPOLOGY 1. The

Topology (H) Lecture 6 Lecturer: Zuoqin Wang Time: March 25, 2021 THE QUOTIENT TOPOLOGY 1. The quotient topology { The quotient topology. Last time we introduced several abstract methods to construct topologies on ab- stract spaces (which is widely used in point-set topology and analysis). Today we will introduce another way to construct topological spaces: the quotient topology. In fact the quotient topology is not a brand new method to construct topology. It is merely a simple special case of the co-induced topology that we introduced last time. However, since it is very concrete and \visible", it is widely used in geometry and algebraic topology. Here is the definition: Definition 1.1 (The quotient topology). (1) Let (X; TX ) be a topological space, Y be a set, and p : X ! Y be a surjective map. The co-induced topology on Y induced by the map p is called the quotient topology on Y . In other words, −1 a set V ⊂ Y is open if and only if p (V ) is open in (X; TX ). (2) A continuous surjective map p :(X; TX ) ! (Y; TY ) is called a quotient map, and Y is called the quotient space of X if TY coincides with the quotient topology on Y induced by p. (3) Given a quotient map p, we call p−1(y) the fiber of p over the point y 2 Y . Note: by definition, the composition of two quotient maps is again a quotient map. Here is a typical way to construct quotient maps/quotient topology: Start with a topological space (X; TX ), and define an equivalent relation ∼ on X. -

1.1.3 Reminder of Some Simple Topological Concepts Definition 1.1.17

1. Preliminaries The Hausdorffcriterion could be paraphrased by saying that smaller neigh- borhoods make larger topologies. This is a very intuitive theorem, because the smaller the neighbourhoods are the easier it is for a set to contain neigh- bourhoods of all its points and so the more open sets there will be. Proof. Suppose τ τ . Fixed any point x X,letU (x). Then, since U ⇒ ⊆ ∈ ∈B is a neighbourhood of x in (X,τ), there exists O τ s.t. x O U.But ∈ ∈ ⊆ O τ implies by our assumption that O τ ,soU is also a neighbourhood ∈ ∈ of x in (X,τ ). Hence, by Definition 1.1.10 for (x), there exists V (x) B ∈B s.t. V U. ⊆ Conversely, let W τ. Then for each x W ,since (x) is a base of ⇐ ∈ ∈ B neighbourhoods w.r.t. τ,thereexistsU (x) such that x U W . Hence, ∈B ∈ ⊆ by assumption, there exists V (x)s.t.x V U W .ThenW τ . ∈B ∈ ⊆ ⊆ ∈ 1.1.3 Reminder of some simple topological concepts Definition 1.1.17. Given a topological space (X,τ) and a subset S of X,the subset or induced topology on S is defined by τ := S U U τ . That is, S { ∩ | ∈ } a subset of S is open in the subset topology if and only if it is the intersection of S with an open set in (X,τ). Alternatively, we can define the subspace topology for a subset S of X as the coarsest topology for which the inclusion map ι : S X is continuous.