Oliver Heaviside: a First-Rate Oddity Bruce J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simple Circuit Theory and the Solution of Two Electricity Problems from The

Simple circuit theory and the solution of two electricity problems from the Victorian Age A C Tort ∗ Departamento de F´ısica Te´orica - Instituto de F´ısica Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Caixa Postal 68.528; CEP 21941-972 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil May 22, 2018 Abstract Two problems from the Victorian Age, the subdivision of light and the determination of the leakage point in an undersea telegraphic cable are discussed and suggested as a concrete illustrations of the relationships between textbook physics and the real world. Ohm’s law and simple algebra are the only tools we need to discuss them in the classroom. arXiv:0811.0954v1 [physics.pop-ph] 6 Nov 2008 ∗e-mail: [email protected]. 1 1 Introduction Some time ago, the present author had the opportunity of reading Paul J. Nahin’s [1] fascinating biog- raphy of the Victorian physicist and electrician Oliver Heaviside (1850-1925). Heaviside’s scientific life unrolls against a background of theoretical and technical challenges that the scientific and technological developments fostered by the Industrial Revolution presented to engineers and physicists of those times. It is a time where electromagnetic theory as formulated by James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879) was un- derstood by only a small group of men, Lodge, FitzGerald and Heaviside, among others, that had the mathematical sophistication and imagination to grasp the meaning and take part in the great Maxwellian synthesis. Almost all of the electrical engineers, or electricians as they were called at the time, considered themselves as “practical men”, which effectively meant that most of them had a working knowledge of the electromagnetic phenomena spiced up with bits of electrical theory, to wit, Ohm’s law and the Joule effect. -

The Concept of Field in the History of Electromagnetism

The concept of field in the history of electromagnetism Giovanni Miano Department of Electrical Engineering University of Naples Federico II ET2011-XXVII Riunione Annuale dei Ricercatori di Elettrotecnica Bologna 16-17 giugno 2011 Celebration of the 150th Birthday of Maxwell’s Equations 150 years ago (on March 1861) a young Maxwell (30 years old) published the first part of the paper On physical lines of force in which he wrote down the equations that, by bringing together the physics of electricity and magnetism, laid the foundations for electromagnetism and modern physics. Statue of Maxwell with its dog Toby. Plaque on E-side of the statue. Edinburgh, George Street. Talk Outline ! A brief survey of the birth of the electromagnetism: a long and intriguing story ! A rapid comparison of Weber’s electrodynamics and Maxwell’s theory: “direct action at distance” and “field theory” General References E. T. Wittaker, Theories of Aether and Electricity, Longam, Green and Co., London, 1910. O. Darrigol, Electrodynamics from Ampère to Einste in, Oxford University Press, 2000. O. M. Bucci, The Genesis of Maxwell’s Equations, in “History of Wireless”, T. K. Sarkar et al. Eds., Wiley-Interscience, 2006. Magnetism and Electricity In 1600 Gilbert published the “De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure” (On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on That Great Magnet the Earth). ! The Earth is magnetic ()*+(,-.*, Magnesia ad Sipylum) and this is why a compass points north. ! In a quite large class of bodies (glass, sulphur, …) the friction induces the same effect observed in the amber (!"#$%&'(, Elektron). Gilbert gave to it the name “electricus”. -

HISTORICAL SURVEY SOME PIONEERS of the APPLICATIONS of FRACTIONAL CALCULUS Duarte Valério 1, José Tenreiro Machado 2, Virginia

HISTORICAL SURVEY SOME PIONEERS OF THE APPLICATIONS OF FRACTIONAL CALCULUS Duarte Val´erio 1,Jos´e Tenreiro Machado 2, Virginia Kiryakova 3 Abstract In the last decades fractional calculus (FC) became an area of intensive research and development. This paper goes back and recalls important pio- neers that started to apply FC to scientific and engineering problems during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Those we present are, in alphabet- ical order: Niels Abel, Kenneth and Robert Cole, Andrew Gemant, Andrey N. Gerasimov, Oliver Heaviside, Paul L´evy, Rashid Sh. Nigmatullin, Yuri N. Rabotnov, George Scott Blair. MSC 2010 : Primary 26A33; Secondary 01A55, 01A60, 34A08 Key Words and Phrases: fractional calculus, applications, pioneers, Abel, Cole, Gemant, Gerasimov, Heaviside, L´evy, Nigmatullin, Rabotnov, Scott Blair 1. Introduction In 1695 Gottfried Leibniz asked Guillaume l’Hˆopital if the (integer) order of derivatives and integrals could be extended. Was it possible if the order was some irrational, fractional or complex number? “Dream commands life” and this idea motivated many mathematicians, physicists and engineers to develop the concept of fractional calculus (FC). Dur- ing four centuries many famous mathematicians contributed to the theo- retical development of FC. We can list (in alphabetical order) some im- portant researchers since 1695 (see details at [1, 2, 3], and posters at http://www.math.bas.bg/∼fcaa): c 2014 Diogenes Co., Sofia pp. 552–578 , DOI: 10.2478/s13540-014-0185-1 SOME PIONEERS OF THE APPLICATIONS . 553 • Abel, Niels Henrik (5 August 1802 - 6 April 1829), Norwegian math- ematician • Al-Bassam, M. A. (20th century), mathematician of Iraqi origin • Cole, Kenneth (1900 - 1984) and Robert (1914 - 1990), American physicists • Cossar, James (d. -

A Solution of the Interpretation Problem of Lorentz Transformations

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 30 July 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202007.0705.v1 Article A Solution of the Interpretation Problem of Lorentz Transformations Grit Kalies* HTW University of Applied Sciences Dresden; 1 Friedrich-List-Platz, D-01069 Dresden, [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected], Tel.: +49-351-462-2552 Abstract: For more than one hundred years, scientists dispute the correct interpretation of Lorentz transformations within the framework of the special theory of relativity of Albert Einstein. On the one hand, the changes in length, time and mass with increasing velocity are interpreted as apparent due to the observer dependence within special relativity. On the other hand, real changes are described corresponding to the experimental evidence of mass increase in particle accelerators or of clock delay. This ambiguity is accompanied by an ongoing controversy about valid Lorentz-transformed thermodynamic quantities such as entropy, pressure and temperature. In this paper is shown that the interpretation problem of the Lorentz transformations is genuinely anchored within the postulates of special relativity and can be solved on the basis of the thermodynamic approach of matter-energy equivalence, i.e. an energetic distinction between matter and mass. It is suggested that the velocity-dependent changes in state quantities are real in each case, in full agreement with the experimental evidence. Keywords: interpretation problem; Lorentz transformation; special relativity; thermodynamics; potential energy; space; time; entropy; non-mechanistic ether theory © 2020 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 30 July 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202007.0705.v1 2 of 25 1. -

Oliver Heaviside (1850-1925) - Physical Mathematician D

Oliver Heaviside (1850-1925) - Physical Mathematician D. A. EDGE. AFIMA The Mary Erskine School, Edinburgh 4m-; JL Mathematics is of two kinds, Rigorous and Physical. The former is Narrow: the latter Downloaded from Bold and Broad. To have to stop to formulate rigorous demonstrations would put a stop to most physico-mathematical enquiries. Am I to refuse to eat because I do not fully understand the mechanism of digestion? Oliver Heaviside http://teamat.oxfordjournals.org/ Preface Details Too little attention is paid on educational courses in Oliver Heaviside was the youngest of four sons of mathematics and science to the personalities of the Thomas Heaviside, then at 55 King Street, Camden great innovators. When teaching at Paisley College Town, London. His mother was formerly Rachel of Technology I was very impressed with the tape- West, who had been a governess in the Spottiswoode slide facilities in the library and I thought that here famjly and whose sister was the wife of Sir Charles was an ideal way of presenting biographical Wheatstone, the telegraphist and prolific inventor. material. Not only would well-prepared material be Thomas Heaviside was a skilful wood-engraver who at University of Iowa Libraries/Serials Acquisitions on June 17, 2015 instructive but also it would be entertaining. moved to London from Teesside with his wife and I was inspired to produce a tape-slide presentation young sons in about 1849. Oliver was born on May on Oliver Heaviside in particular by an excellent 18th, 1850. radio talk by Dr. D. M. A. Mercer.1 The essay below It has been suggested2 that the Heaviside family is along the lines of my script and is presented with a moved to London because the development of view to interesting others in Heaviside and perhaps photography was making wood-engravers redun- in the idea mentioned at the outset dant and there were better prospects of employment Summary in the capital. -

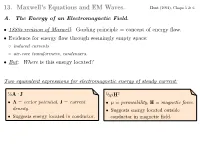

13. Maxwell's Equations and EM Waves. Hunt (1991), Chaps 5 & 6 A

13. Maxwell's Equations and EM Waves. Hunt (1991), Chaps 5 & 6 A. The Energy of an Electromagnetic Field. • 1880s revision of Maxwell: Guiding principle = concept of energy flow. • Evidence for energy flow through seemingly empty space: ! induced currents ! air-core transformers, condensers. • But: Where is this energy located? Two equivalent expressions for electromagnetic energy of steady current: ½A J ½µH2 • A = vector potential, J = current • µ = permeability, H = magnetic force. density. • Suggests energy located outside • Suggests energy located in conductor. conductor in magnetic field. 13. Maxwell's Equations and EM Waves. Hunt (1991), Chaps 5 & 6 A. The Energy of an Electromagnetic Field. • 1880s revision of Maxwell: Guiding principle = concept of energy flow. • Evidence for energy flow through seemingly empty space: ! induced currents ! air-core transformers, condensers. • But: Where is this energy located? Two equivalent expressions for electrostatic energy: ½qψ# ½εE2 • q = charge, ψ = electric potential. • ε = permittivity, E = electric force. • Suggests energy located in charged • Suggests energy located outside object. charged object in electric field. • Maxwell: Treated potentials A, ψ as fundamental quantities. Poynting's account of energy flux • Research project (1884): "How does the energy about an electric current pass from point to point -- that is, by what paths and acording to what law does it travel from the part of the circuit where it is first recognizable as electric and John Poynting magnetic, to the parts where it is changed into heat and other forms?" (1852-1914) • Solution: The energy flux at each point in space is encoded in a vector S given by S = E × H. -

Oliver Heaviside 1850-1925

Oliver Heaviside 1850-1925 The words inductance, capacitance, and impedance were given to us by the great English physicist and engineer, Oliver Heaviside, who also pioneered in the use of Laplace and Fourier transforms in the analysis of electric circuits, first suggested the existence of an ionized atmospheric layer (now called the ionosphere) that can reflect radio waves, and is said to have predicted the increase of mass of a charge moving at great speeds before Einstein formulated his theory of relativity. He not only coined the word impedance but introduced its concept to the solution of ac circuits. Heaviside was born in London, the youngest of four sons of Thomas Heaviside, an engraver and watercolorist, and Rachel Elizabeth West, a sister-in-law of the famous physicist Sir Charles Wheatstone. Young Oliver's schooling ended when he was 16, but he trained himself at home in languages, mathematics, and the natural sciences. He became a telegraph operator in 1870, but in 1874 he was forced to retire because of increasing deafness. From then until his death he led a hermit like existence, devoting himself to investigations of electrical phenomena and publishing such works as Electrical Papers in 1892 and a three-volume treatise, Electromagnetic Theory (1893 – 1912). His free and original use of mathematics was decades ahead of his time and evoked controversy with his contemporaries. Nevertheless, his fame spread, and because of his great store of knowledge and the scientific help he generously extended to all who sought it, his home became known as The Inexhaustible Cavity. He was elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1891 and received an honorary doctorate from the University of Gottingen. -

The Daniell Cell, Ohm's Law and the Emergence of the International System of Units

The Daniell Cell, Ohm’s Law and the Emergence of the International System of Units Joel S. Jayson∗ Brooklyn, NY (Dated: December 24, 2015) Telegraphy originated in the 1830s and 40s and flourished in the following decades, but with a patchwork of electrical standards. Electromotive force was for the most part measured in units of the predominant Daniell cell. Each company had their own resistance standard. In 1862 the British Association for the Advancement of Science formed a committee to address this situation. By 1873 they had given definition to the electromagnetic system of units (emu) and defined the practical units of the ohm as 109 emu units of resistance and the volt as 108 emu units of electromotive force. These recommendations were ratified and expanded upon in a series of international congresses held between 1881 and 1904. A proposal by Giovanni Giorgi in 1901 took advantage of a coincidence between the conversion of the units of energy in the emu system (the erg) and in the practical system (the joule) in that the same conversion factor existed between the cgs based emu system and a theretofore undefined MKS system. By introducing another unit, X (where X could be any of the practical electrical units), Giorgi demonstrated that a self consistent MKSX system was tenable without the need for multiplying factors. Ultimately the ampere was selected as the fourth unit. It took nearly 60 years, but in 1960 Giorgi’s proposal was incorporated as the core of the newly inaugurated International System of Units (SI). This article surveys the physics, physicists and events that contributed to those developments. -

The Beauty of Equations

Proceedings of Bridges 2013: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture The Beauty of Equations Robert P. Crease Philosophy Department Stony Brook University Stony Brook, NY 11794 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper discusses grounds for ascribing beauty to equations. Philosophical accounts of beauty in the context of science tend to stress one or more of three aspects of beautiful objects: depth, economy, and definitiveness. The paper considers several cases that engage these aspects in different ways, depending on whether the equation is considered as a signpost, as a stand-in for a phenomenon, as making a disciplinary transformation, or as inspiring a personal revelation. Introduction Certain equations have become more than scientific tools or educational instruments, and exert what might be called cultural force. A few equations have acquired celebrity status in that people recognize them while knowing next to nothing about them, while other equations attract fascination and awe because they are thought to harbor deep significance. For these reasons, equations are frequently encountered outside science and mathematics, and even turn up in novels, plays, and films, having effectively acquired the status of cultural touchstones. Sometimes what the public encounters in the form of an equation is simply an ordinary thought cloaked in mathematical dress. Even the form of certain equations can be culturally influential, as when instructions for behavior are presented as equations. Several recent books have broached the subject of the meaning, greatness, or aesthetic value of certain important equations [1-5]. I want to discuss the last of these subjects: aesthetics. Scientists do sometimes ascribe beauty to theories or equations, and occasionally declare beauty to be an essential property of fundamental equations. -

18 Gauge Fields, Coordinate Systems, and Geometric Phases

18 Gauge felds, coordinate systems, and geometric phases 18.1 Maxwell’s equations Maxwell said 1 ∂B! Faraday’s law E! = (18.1) ∇× − c ∂t 1 ∂D! Ampère’s law H! = !j + (18.2) ∇× c ! ∂t " Coulomb’s law D! = ρ (18.3) ∇ no magnetic monopoles B! =0 (18.4) ∇ and it was light [43, 44]. Together with Newton’s laws of classical mechanics and the Lorentz force !v F! = q E! + B! (18.5) c × # $ that was all what was known fundamentally about physics by the end of the 19th century. Maxwell originally didn’t write his equations in the modern notation using vectors we are familiar with. This was introduced later by Oliver Heaviside [45] and Josiah Willard Gibbs, making the equations much easier to read (and evaluate). Instead, Maxwell used 20 scalar felds, inspired by the then-popular fuid mechanics. Also his equations contain explicitly the vector potential A!, which can be eliminated from his equations. The equations for the 16 parameters above above include the relations B! = µ0 H! + λM! , (18.6) % & D! = %0E! + λP,! (18.7) introducing the macroscopic magnetization M! and electric polarization P! with the mag- netic permeability µ0 and the dielectric constant %0. The factor λ denotes a dimension- 281 18 Gauge felds, coordinate systems, and geometric phases Table 18.1: Defnitions of µ0, %0, and λ in different unit systems Unit system µ0 %0 λ 7 2 Système Internationale 4π 10− T /(A/m) 1/(µ0c )1 × Gauß 1 14π Heaviside-Lorentz 1 11 esu 1/c2 14π emu 1 1/c2 4π less constant depending on the unit system chosen.1 We are using Heaviside-Lorentz units (named after Oliver Heaviside and Hendrik Antoon Lorentz), equivalent to setting µ0 = %0 = λ =1. -

Celebrating 125 Years of Oliver Heaviside's 'Electromagnetic Theory'

ISSN 1364-503X | Volume 376 | Issue 2134 | 13 December 2018 Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A | R. Soc. A Phil. Trans. The Royal Society is a self-governing Fellowship of many of the world’s most distinguished scientists drawn from all areas of science, engineering, and medicine. The Society’s fundamental purpose, as it 376 Volume has been since its foundation in 1660, is to recognise, promote, and support excellence in science and to Celebrating 125 years of Oliver Heaviside’s ‘Electromagnetic encourage the development and use of science for Theory’ the benefi t of humanity. | Issue 2134 Theme issue compiled and edited by Christopher Donaghy-Spargo and Alex Yakovlev The Society’s strategic priorities emphasise its commitment to the highest quality science, to curiosity-driven research, and to the development | and use of science for the benefi t of society. 13 December 2018 These priorities are: • Promoting science and its benefi ts • Recognising excellence in science • Supporting outstanding science • Providing scientifi c advice for policy • Fostering international and global cooperation ‘Electromagnetic Theory’ 125 years of Oliver Heaviside’s • Education and public engagement For further information on the Royal Society The Royal Society 6 – 9 Carlton House Terrace London SW1Y 5AG T +44 20 7451 2500 W royalsociety.org For further information on Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A T +44 20 7451 2214 E [email protected] W rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org 1364-503X(20181213)376:2134 ISBN: 978-1-78252-358-1 ISSN 1364-503X The Royal Society Registered Charity No 207043 RSTA_376_2134_Cover.indd 2-4 30/10/18 5:13 PM Oliver Heaviside’s electromagnetic theory rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org Christopher Donaghy-Spargo1 and Alex Yakovlev2 1Department of Engineering, Durham University, South Road, Durham DH1 3LE, UK Introduction 2School of Engineering, Newcastle University, Merz Court, Cite this article: Donaghy-Spargo C, Yakovlev NewcastleuponTyneNE17RU,UK A. -

Heaviside's Operator Calculus

Heaviside’s Operator Calculus ©2007-2009 Ron Doerfler Dead Reckonings: Lost Art in the Mathematical Sciences http://www.myreckonings.com/wordpress May 14, 2009 An operational calculus converts derivatives and integrals to operators that act on functions, and by doing so ordinary and partial linear differential equations can be reduced to purely algebraic equations that are much easier to solve. There have been a number of operator methods created as far back as Liebniz, and some operators such as the Dirac delta function created controversy at the time among mathematicians, but no one wielded operators with as much flair and abandon over the objections of mathematicians as Oliver Heaviside, the reclusive physicist and pioneer of electromagnetic theory. The name of Oliver Heaviside (1850-1925) is not well-known to the general public today. However, it was Heaviside, for example, who developed Maxwell’s electromagnetic equations into the four vector calculus equations in two unknowns that we are familiar with today; Maxwell left them as 20 equations in 20 unknowns expressed as quaternions, a once-popular mathematical system currently experiencing a revival for fast coordinate transformations in video games. Heaviside also did important early work in long-distance telegraphy and telephony, introducing induction-loading of long cables to minimize distortion and patenting the coaxial cable. At one time the ionosphere was called the Heaviside layer after his suggestion (and that of Arthur Kennelly) that a layer of charged ions in the upper atmosphere (now just one layer of the ionosphere) would account for the puzzlingly long distances that radio waves traveled.