A History and Critical Analysis of Namibia's Archaeologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Further Evidence for Bow Hunting and Its Implications More Than 60 000

1 Further evidence for bow hunting and its implications more than 60 000 2 years ago: results of a use-trace analysis of the bone point from Klasies River 3 Main site, South Africa. 4 5 Justin Bradfield1*, Marlize Lombard1, Jerome Reynard2, Sarah Wurz2,3 6 1. Palaeo-Research Institute, University of Johannesburg, P.O. Box 524, Auckland Park, 2006, 7 Johannesburg, South Africa 8 2. School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Science, University of the 9 Witwatersrand 10 3. SFF Centre for Early Sapiens Behaviour (SapiensCE), University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway 11 * [email protected] 12 13 14 15 Abstract 16 The bone point (SAM 42160) from >60 ka deposits at Klasies River Main Site, South Africa, is 17 reassessed. We clarify the stratigraphic integrity of SAM 42160 and confirm its Middle Stone 18 Age provenience. We find evidence that indicates the point was hafted and partially coated 19 in an adhesive substance. Internal fractures are consistent with stresses occasioned by high- 20 velocity, longitudinal impact. SAM 42160, like its roughly contemporaneous counterpart, 21 farther north at Sibudu Cave, likely functioned as a hafted arrowhead. We highlight a 22 growing body of evidence for bow hunting at this early period and explore what the 23 implications of bow-and-arrow technology might reveal about the cognition of Middle Stone 24 Age people who were able to conceive, construct and use it. 25 26 Keywords: arrowhead; bone point; bow hunting; traceology; cognition, palaeo-neurology; 27 symbiotic technology 28 29 30 31 1. Introduction 32 Multiple lines of evidence have been mounting over the last decade to support bow hunting 33 in South Africa before 60 ka. -

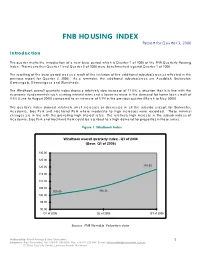

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006 Introduction This quarter marks the introduction of a new base period which is Quarter 1 of 2006 of the FNB Quarterly Housing Index. This means that Quarter 2 and Quarter 3 of 2006 were benchmarked against Quarter 1 of 2006. The resetting of the base period was as a result of the inclusion of five additional suburbs/areas as reflected in the previous report for Quarter 2, 2006. As a reminder, the additional suburbs/areas are Auasblick, Brakwater, Goreangab, Okuryangava and Wanaheda. The Windhoek overall quarterly index shows a relatively slow increase of 11.6%, a situation that is in line with the economic fundamentals such as rising interest rates and a lower increase in the demand for home loan credit of 3.6% (June to August 2006) compared to an increase of 5.9% in the previous quarter (March to May 2006). This quarter’s index showed relatively small increases or decreases in all the suburbs except for Brakwater, Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park where moderate to high increases were recorded. These minimal changes are in line with the prevailing high interest rates. The relatively high increase in the suburb indices of Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park could be ascribed to a high demand for properties in these areas. Figure 1: Windhoek Index Windhoek overall quarterly index - Q3 of 2006 (Base: Q1 of 2006) 130.00 125.00 120.00 118.55 115.00 110.00 105.00 100.00 106.22 100.00 95.00 90.00 Q1 of 2006 Q2 of 2006 Q3 of 2006 Source: FNB Namibia Valuation data Authored by: Martin Mwinga & Alex Shimuafeni 1 Enquiries: Alex Shimuafeni, Tel: +264 61 2992890, Fax: +264 61 225 994, E-mail: [email protected] 5th Floor, First City Centre, Levinson Arcade, Windhoek Brakwater recorded an extraordinary high quarterly increase of 72% from Quarter 2. -

Touring Katutura! : Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism In

Universität Potsdam Malte Steinbrink | Michael Buning | Martin Legant | Berenike Schauwinhold | Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA ! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Potsdamer Geographische Praxis Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Malte Steinbrink|Michael Buning|Martin Legant| Berenike Schauwinhold |Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de/ abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2016 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: -2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Die Schriftenreihe Potsdamer Geographische Praxis wird herausgegeben vom Institut für Geographie der Universität Potsdam. ISSN (print) 2194-1599 ISSN (online) 2194-1602 Das Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Gestaltung: André Kadanik, Berlin Satz: Ute Dolezal Titelfoto: Roman Behrens Druck: docupoint GmbH Magdeburg ISBN 978-3-86956-384-8 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam: URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 11 1.1 Background of the study: -

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location Henning Melber1 Abstract The Windhoek Old Location refers to what had been the South West African capital’s Main Lo- cation for the majority of black and so-called Colored people from the early 20th century until 1960. Their forced removal to the newly established township Katutura, initiated during the late 1950s, provoked resistance, popular demonstrations and escalated into violent clashes between the residents and the police. These resulted in the killing and wounding of many people on 10 December 1959. The Old Location since became a synonym for African unity in the face of the divisions imposed by apartheid. Based on hitherto unpublished archival documents, this article contributes to a not yet exist- ing social history of the Old Location during the 1950s. It reconstructs aspects of the daily life among the residents in at that time the biggest urban settlement among the colonized majority in South West Africa. It revisits and portraits a community, which among former residents evokes positive memories compared with the imposed new life in Katutura and thereby also contributed to a post-colonial heroic narrative, which integrates the resistance in the Old Location into the patriotic history of the anti-colonial liberation movement in government since Independence. O Lord, help us who roam about. Help us who have been placed in Africa and have no dwelling place of our own. Give us back a dwelling place.2 The Old Location was the Main Location for most of the so-called non-white residents of Wind- hoek from the early 20th century until 1960, while a much smaller location also existed until 1961 in Klein Windhoek. -

Public Notice Electoral Commission of Namibia

The Electoral Commission of Namibia herewith publishes the names of the Political Party lists of Candidates for the National Assembly elections which will be gazzetted on 7th November 2019. If any person’s name appears on a list without their consent, they can approach the Commission in writing in terms of Section 78 (2) of the Electoral Act, No. 5 of 2014. In such cases the Electoral Act of 2014 empowers the Commission to make withdrawals or removals of candidates after gazetting by publishing an amended notice. NATIONAL ASSEMBY ELECTIONS POLITICAL PARTIES CANDIDATE LIST 2019 PUBLIC NOTICE ELECTORAL COMMISSION OF NAMIBIA NOTIFICATION OF REGISTERED POLITICAL PARTIES AND LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR REGISTERED POLITICAL PARTIES: GENERAL ELECTION FOR ELECTION OF MEMBERS OF NATIONAL ASSEMBLY: ELECTORAL ACT, 2014 In terms of section 78(1) of the Electoral Act, 2014 (Act no. 5 of 2014), the public is herewith notified that for the purpose of the general election for the election of members of the National Assembly on 27 November 2019 – (a) The names of all registered political parties partaking in the general election for the election of the members of the National Assembly are set out in Schedule 1; (b) The list of candidates of each political party referred to in paragraph (a), as drawn up by the political parties and submitted in terms of section 77 of that Act for the election concerned is set out in Schedule 2; and (c) The persons whose names appear on that list referred to in paragraph (b) have been duly nominated as candidates of the political party concerned for the election. -

Public Perception of Windhoek's Drinking Water and Its Sustainable

Public Perception of Windhoek’s Drinking Water and its Sustainable Future A detailed analysis of the public perception of water reclamation in Windhoek, Namibia By: Michael Boucher Tayeisha Jackson Isabella Mendoza Kelsey Snyder IQP: ULB-NAM1 Division: 41 PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF WINDHOEK’S DRINKING WATER AND ITS SUSTAINABLE FUTURE A DETAILED ANALYSIS OF THE PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF WATER RECLAMATION IN WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA AN INTERACTIVE QUALIFYING PROJECT REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE SPONSORING AGENCY: Department of Infrastructure, Water and Waste Management The City of Windhoek SUBMITTED TO: On-Site Liaison: Ferdi Brinkman, Chief Engineer Project Advisor: Ulrike Brisson, WPI Professor Project Co-advisor: Ingrid Shockey, WPI Professor SUBMITTED BY: ____________________________ Michael Boucher ____________________________ Tayeisha Jackson ____________________________ Isabella Mendoza ____________________________ Kelsey Snyder Abstract Due to ongoing water shortages and a swiftly growing population, the City of Windhoek must assess its water system for future demand. Our goal was to follow up on a previous study to determine the public perception of the treatment process and the water quality. The broader sample portrayed a lack of awareness of this process and its end product. We recommend the City of Windhoek develop educational campaigns that inform its citizens about the water reclamation process and its benefits. i Executive Summary Introduction and Background Namibia is among the most arid countries in southern Africa. Though it receives an average of 360mm of rainfall each year, 83 percent of this water evaporates immediately after rainfall. Another 14 percent goes towards vegetation, and 1 percent supplies the ground water in the region, thus leaving merely 2 percent for surface use. -

Khomas Regional Development Profile 2015

KHOMAS REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROFILE 2015 Khomas Regional Council PO Box 3379, Windhoek Tel.: +264 61 292 4300 http://209.88.21.122/web/khomasrc Khomas Regional Development Profile 2015 Page i KHOMAS REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROFILE 2015 ENQUIRIES [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] http://209.88.21.122/web/khomasrc TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms iii List of Charts, Maps and Tables vi Acknowledgment 1 Foreword 2 Executive Summary 3 Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1. Introduction to the region 5 Location 6 Size of the region 7 Population and demography 7 Landscape 8 1.2. Governance and Planning Structures 15 1.3. High Level Statements of the Khomas Regional Council 17 1.4. Methodology 18 Chapter 2: Key Statistics 2.1. Demographics 20 2.1.1 Population size 20 2.1.2 Population size per constituency 20 2.1.3 Age composition 21 2.1.4 Population groups 22 2.1.5 Unemployment rate 23 2.1.6 Average Life Expectancy 24 2.1.7 Poverty Prevalence in Khomas Region 24 2.2. Household Percentage with access to: 26 Safe water 26 Health facilities 26 Sanitation 27 Chapter 3: Regional Development Areas 28 3.1. Economic Sector 28 Agriculture 28 Tourism and Wildlife 28 Trade and Industrial Development 29 Mining 30 3.2. Social Sector 30 Housing 30 Health (and health facilities) 34 KRDP 2015 – Table of Contents i Water and Sanitation accessibility 36 Education and Training 38 3.3. Infrastructure 39 Transport 40 Roads 40 Air 40 Railway 40 Water and Sanitation Infrastructure 43 Telecommunication 44 3.4. -

AREA REGION 1 Caprivi Pharmacy Caprivi 2 Katima Pharmacy Caprivi

NAME Designation AREA REGION 1 Caprivi Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Katima Mulilo Caprivi 2 Katima Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Ngweze Caprivi 3 Henties Bay Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Henties Bay Erongo 4 Karibib Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Karibib Erongo 5 Narraville Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Narraville Erongo 6 Ocean View Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Ocean View Erongo 7 Adler Apotheke Pharmacies - Retail Swakopmund Erongo 8 Bismarck Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Swakopmund Erongo 9 Dolphin Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Swakopmund Erongo 10 Medcare Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Swakopmund Erongo 11 Nash Health Style T/a Mondesa Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Swakopmund Erongo 12 Pro Park Pharmacy cc Pharmacies - Retail Swakopmund Erongo 13 Swakopmunder Apotheke Pharmacies - Retail Swakopmund Erongo 14 Vineta Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Swakopmund Erongo 15 Molenzicht Pharmacy cc T/a Central Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Tamariskia Erongo 16 F Y Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Vineta Erongo 17 A B C Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Walvis Bay Erongo 18 Kuisebmund Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Walvis Bay Erongo 19 Oasis Pharmacy Pharmacies - Retail Walvis Bay Erongo 20 Sentrum Apteek Pharmacies - Retail Walvis Bay Erongo 21 Walvis Bay Pharmacy Incorporated Pharmacies - Retail Walvis Bay Erongo 22 Mediclinic Cottage - Pharmacy Pharmacies - Pvt Hospitals Swakopmund Erongo 23 Walvis Bay Medipark T/a Welwitchia Hospital Pharmacy Pharmacies - Pvt Hospitals Walvis Bay Erongo 24 Chrismed Pharmacy cc Pharmacies - Retail Rehoboth Hardap 25 Hardap Pharmacy -

Water Consumption at Household Level in Windhoek, Namibia

Uhlendahl et al.: Water consumption Windhoek 2010 Albert Ludwigs University Institute for Culture Geography Final Project Report: Water consumption at household level in Windhoek, Namibia Survey about water consumption at household level in different areas of Windhoek depending on income level and water access in 2010 Authors: Dr. T. Uhlendahl and D. Ziegelmayer, Institute of Cultural Geography, Albert- Ludwigs University of Freiburg, Dr. A. Wienecke and M. L. Mawisa, Habitat Research and Development Center (HRDC) and Piet du Pisani, City of Windhoek (CoW) Project in cooperation with: Polytechnic of Namibia and Shack Dweller Federation of Namibia (SDFN) & Namibia Housing Action Group (NHAG) SDFN & NHAG Uhlendahl et al.: Water consumption Windhoek 2010 Table of contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 2. Targets............................................................................................................. 2 2.1. Water consumption depending on income level .............................................. 2 2.2. Specific purposes for which water is used ....................................................... 2 2.3. Evaluation of Windhoek’s water supply............................................................ 2 2.4. Approaches...................................................................................................... 3 3. State of knowledge ......................................................................................... -

Humanity from African Naissance to Coming Millennia” Arises out of the World’S First G

copertina2 12-12-2000 12:55 Seite 1 “Humanity from African Naissance to Coming Millennia” arises out of the world’s first J. A. Moggi-Cecchi Doyle G. A. Raath M. Tobias V. P. Dual Congress that was held at Sun City, South Africa, from 28th June to 4th July 1998. “Dual Congress” refers to a conjoint, integrated meeting of two international scientific Humanity associations, the International Association for the Study of Human Palaeontology - IV Congress - and the International Association of Human Biologists. As part of the Dual Congress, 18 Colloquia were arranged, comprising invited speakers on human evolu- from African Naissance tionary aspects and on the living populations. This volume includes 39 refereed papers from these 18 colloquia. The contributions have been classified in eight parts covering to Coming Millennia a wide range of topics, from Human Biology, Human Evolution (Emerging Homo, Evolving Homo, Early Modern Humans), Dating, Taxonomy and Systematics, Diet, Brain Evolution. The book offers the most recent analyses and interpretations in diff rent areas of evolutionary anthropology, and will serve well both students and specia- lists in human evolution and human biology. Editors Humanity from African Humanity Naissance from to Coming Millennia Phillip V. Tobias Phillip V. Tobias is Professor Emeritus at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where he Michael A. Raath obtained his medical doctorate, PhD and DSc and where he served as Chair of the Department of Anatomy for 32 years. He has carried out researches on mammalian chromosomes, human biology of the peoples of Jacopo Moggi-Cecchi Southern Africa, secular trends, somatotypes, hominin evolution, the history of anatomy and anthropology. -

Government Gazette Republic of Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$10.80 WINDHOEK - 19 March 2021 No. 7488 Advertisements PROCEDURE FOR ADVERTISING IN 7. No liability is accepted for any delay in the publi- THE GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE cation of advertisements/notices, or for the publication of REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA such on any date other than that stipulated by the advertiser. Similarly no liability is accepted in respect of any editing, 1. The Government Gazette (Estates) containing adver- revision, omission, typographical errors or errors resulting tisements, is published on every Friday. If a Friday falls on from faint or indistinct copy. a Public Holiday, this Government Gazette is published on the preceding Thursday. 8. The advertiser will be held liable for all compensa- tion and costs arising from any action which may be insti- 2. Advertisements for publication in the Government tuted against the Government of Namibia as a result of the Gazette (Estates) must be addressed to the Government Ga- publication of a notice with or without any omission, errors, zette office, Private Bag 13302, Windhoek, or be delivered lack of clarity or in any form whatsoever. at Justitia Building, Independence Avenue, Second Floor, Room 219, Windhoek, not later than 12h00 on the ninth 9. The subscription for the Government Gazette is working day before the date of publication of this Govern- N$4,190-00 including VAT per annum, obtainable from ment Gazette in which the advertisement is to be inserted. Solitaire Press (Pty) Ltd., corner of Bonsmara and Brahman Streets, Northern Industrial Area, P.O. Box 1155, Wind- 3. -

New Ages from Boomplaas Cave, South Africa, Provide Increased Resolution on Late/Terminal Pleistocene Human Behavioural Variabil

AZANIA: ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN AFRICA, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2018.1436740 New ages from Boomplaas Cave, South Africa, provide increased resolution on late/terminal Pleistocene human behavioural variability Justin Pargetera, Emma Loftusb, Alex Mackayc, Peter Mitchelld and Brian Stewarte aAnthropology Department, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11790, United States of America and Centre for Anthropological Research & Department of Anthropology and Development Studies University of Johannesburg, PO Box 524, Auckland Park, 2006, South Africa; bResearch Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3QY, United Kingdom and Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7700, South Africa; cCentre for Archaeological Science, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia and Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7700, South Africa; dSchool of Archaeology, University of Oxford/St Hugh’s College, Oxford, OX2 6LE, United Kingdom and School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, PO Wits 2050, South Africa; eMuseum of Anthropological Archaeology and Department of Anthropology, University of Michigan, 1109 Geddes Ave., Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1079, United States of America and Rock Art Research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, PO Wits 2050, South Africa. ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Boomplaas Cave, South Africa, contains a rich archaeological