Mythology in Children's Animation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Goblinlike, Fantastic: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40443/ Version: Full Version Citation: Fergus, Emily (2019) ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email ‘Goblinlike, Fantastic’: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle Emily Fergus Submitted for MPhil Degree 2019 Birkbeck, University of London 2 I, Emily Fergus, confirm that all the work contained within this thesis is entirely my own. ___________________________________________________ 3 Abstract This thesis offers a new reading of how little people were presented in both fiction and non-fiction in the latter half of the nineteenth century. After the ‘discovery’ of African pygmies in the 1860s, little people became a powerful way of imaginatively connecting to an inconceivably distant past, and the place of humans within it. Little people in fin de siècle narratives have been commonly interpreted as atavistic, stunted warnings of biological reversion. I suggest that there are other readings available: by deploying two nineteenth-century anthropological theories – E. B. Tylor’s doctrine of ‘survivals’, and euhemerism, a model proposing that the mythology surrounding fairies was based on the existence of real ‘little people’ – they can also be read as positive symbols of the tenacity of the human spirit, and as offering access to a sacred, spiritual, or magic, world. -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

School of Animation & Visual Effects Program Brochure

School of Animation & Visual Effects academyart.edu SCHOOL OF ANIMATION & VISUAL EFFECTS Contents Program Overview ................................................. 5 What We Teach ....................................................... 7 The School of Animation & VFX Difference ........... 9 Faculty .................................................................... 11 Degree Options ...................................................... 13 Our Facilities .......................................................... 15 Student & Alumni Testimonials ............................ 17 Partnerships .......................................................... 19 Career Paths .......................................................... 21 Additional Learning Experiences ..........................23 Awards and Accolades ..........................................25 Online Education ...................................................27 Academy Life .........................................................29 San Francisco ........................................................ 31 Athletics .................................................................33 Apply Today ...........................................................35 < Student work by Jenny Wan 3 SCHOOL OF ANIMATION & VISUAL EFFECTS Program Overview The School of Animation and Visual Effects (VFX) is one of the most dynamic programs in the country. Join us, and get hands-on experience with the full animation and VFX production pipeline. OUR MISSION WHAT SETS US APART In the School of Animation -

The Secret of Kells in 2010 and for Song of the Sea in 2015

The EDUCATIONAL KIT Secret of Kells Tomm Moore, Nora Twomey CONTENT p.3 GENERAL INFORMATION p.4 Synopsis p.5 FILM ANALYSIS p.5 p.6 Film context Expressive means p.6 p.8 Historical context Recognition Image 1 p.10 CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES p.10 p.13 p.15 Starter activity Animated colours The “real” face of and shapes the Vikings p.11 The hero’s journey p.14 Filmic means and director’s choices 2 GENERAL INFORMATION TOMM MOORE (1977, IRELAND) NORA TWOMEY (1971, IRELAND). The film, which is set in the early ninth-century monastic settlement of Kells, is based on a concept which Moore had been exploring a decade earlier while a student of animation at Ballyfermot Senior College in Dublin in 1999. With his co-director Nora Twomey, Moore and the Cartoon Saloon studio have achieved international acclaim for their work, including nominations in the Best Animated Feature Film category at the Oscars for The Secret of Kells in 2010 and for Song of the Sea in 2015. More recently, Twomey’s The Breadwinner (2017), which is set in Afghanistan and stylistically encompasses a more naturalistic and real- world look, also received an Academy nomination for Best Animated Feature in 2018. Moore is currently co-directing a third animated feature, Wolfwalkers, a mythic tale set in Kilkenny that is inspired by local history and legends and is due for release in late 2020. Image 2 Image 3 Twomey is currently directing the 2D American-Irish animation film My Father’s dragon, due for release in 2021. -

How the Filmography of Hayao Miyazaki Subverts Nation Branding and Soft Power

View metadata, citation and similarbrought COREpapers to youat core.ac.ukby provided by University of Tasmania Open Access Repository 1 Wings and Freedom, Spirit and Self: How the Filmography of Hayao Miyazaki Subverts Nation Branding and Soft Power Shadow (BA Hons) 195408 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Journalism, Media and Communications University of Tasmania June, 2015 2 Declaration of Originality: This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of the my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. X Shadow Date: 6/10/2015 Authority of Access: This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. X Shadow Date: 6/10/2015 3 Declaration of Copy Editing: Professional copy was provided by Walter Leggett to amend issues with consistency, spelling and grammar. No other content was altered by Mr Leggett and editing was undertaken under the consent and recommendation of candidate’s supervisors. X Shadow Date: 6/10/2015 4 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 1 ............................................................................................................................. -

Magical Creatures in Isadora Moon

The Magical Creatures of Isadora Moon In the Isadora Moon stories, Isadora’s mum is a fairy and her dad is a vampire. This means that, even though Isadora lives in the human world, she has adventures with lots of fantastical creatures. Harriet Muncaster writes and draws the Isadora Moon books. Writers like Harriet often look at stories and legends from the past to get ideas for their own stories. What are some of the legends that Harriet looked at when telling the story of Isadora Moon, and what has she changed to make her stories as unique as Isadora herself? Fairies In the modern day, we picture fairies as tiny human-like creatures with wings like those of dragonflies or butterflies. However, up until the Victorian age (1837- 1901), the word ‘fairy’ meant any magical creature or events and comes from the Old French word faerie, which means ‘enchanted’. Goblins, pixies, dwarves and nymphs were all called ‘fairies’. These different types of fairies usually did not have wings, and were sometimes human- sized instead of tiny. They could also be good or bad, either helping or tricking people. Luckily, Isadora’s mum, Countess Cordelia Moon, is a good fairy, who likes baking magical cakes, planting colourful flowers, and spending time in nature. Like most modern fairies, she has wings, magical powers, and a close connection with nature, but unlike fairies in some stories, she is human-size. Isadora’s mum can fly using her fairy wings and can use her magic wand to bring toys to life, make plants grow anywhere, and change the appearance of different objects, such as Isadora’s tent. -

The Hercules Story Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE HERCULES STORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin W. Bowman | 128 pages | 01 Aug 2009 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752450810 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom The Hercules Story PDF Book More From the Los Angeles Times. The god Apollo. Then she tried to kill the baby by sending snakes into his crib. Hercules was incredibly strong, even as a baby! When the tasks were completed, Apollo said, Hercules would become immortal. Deianira had a magic balm which a centaur had given to her. July 23, Hercules was able to drive the fearful boar into snow where he captured the boar in a net and brought the boar to Eurystheus. Greek Nyx: The Goddess of the Night. Eurystheus ordered Hercules to bring him the wild boar from the mountain of Erymanthos. Like many Greek gods, Poseidon was worshiped under many names that give insight into his importance Be on the lookout for your Britannica newsletter to get trusted stories delivered right to your inbox. Athena observed Heracles shrewdness and bravery and thus became an ally for life. The name Herakles means "glorious gift of Hera" in Greek, and that got Hera angrier still. Feb 14, Alexandra Dantzer. History at Home. Hercules was born a demi-god. On Wednesday afternoon, Sorbo retweeted a photo of some of the people who swarmed the U. Hercules could barely hear her, her whisper was that soft, yet somehow, and just as the Oracle had predicted to herself, Hera's spies discovered what the Oracle had told him. As he grew and his strength increased, Hera was evermore furious. -

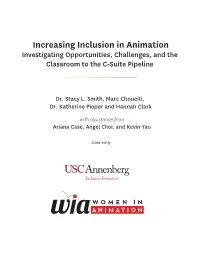

Increasing Inclusion in Animation

INCLUSION IN ANIMATION? INVESTIGATING OPPORTUNITIES, CHALLENGES, AND THE CLASSROOM TO THE CSUITE PIPELINE USC ANNENBERG INCLUSION INITIATIVE @Inclusionists @wia_animation FEMALES ON SCREEN IN ANIMATED STORYTELLING Percentage of animated films with a female lead or co lead and female cast in TV series 120 Animated Films 100 Animated TV Series % of roles for women of color 3% Film 1717% 39% 12% TV Depicted a Female Female Lead or Cast Co Lead ANIMATED AND LIVE ACTION FEMALE PRODUCERS Percentage of female producers across 1,200 films Animation Live Action 64 52 50 50 40 37 33 34 31 26 22 12 13 15 16 14 13 14 15 16 17 15 19 17 ‘07 ‘08 ‘09 ‘10 ‘11 ‘12 ‘13 ‘14 ‘15 ‘16 ‘17 ‘18 OVERALL WOMEN OF COLOR 37% 15% 5% 1% ANIMATION LIVE ACTION ANIMATION LIVE ACTION © DR. STACY L. SMITH FEMALE DIRECTORS ARE RARE IN ANIMATION Directors by platform across film & TV FILM DIRECTORS TV DIRECTORS 3% 13% WOMEN WOMEN 1% 2% WOMEN OF COLOR WOMEN OF COLOR PIPELINE PROBLEMS: CAREER PROGRESS STALLS FOR FEMALES Percentage of Females in the pipeline to directing animated feature films 3% DIRECTORS 7% 8% 9% HEAD OF STORY HEAD OF ANIMATION WRITERS 18% 16% STORY DEPT. ANIMATORS © DR. STACY L. SMITH WOMEN BELOW THE LINE IN TOP ANIMATED TV SERIES WOMEN WOMEN OF COLOR STORY EDITOR 28% 1% HEAD OF EDITING 18% 4% ANIMATION DIRECTOR 16% 8% LEAD ANIMATOR 20% 13% LEAD CHARACTER DESIGNER 24% 7% LEAD STORYBOARD ARTIST 11% 3% TOTAL 19% 7% FEMALE PRODUCERS BY POSITION Percentage of female producers across 100 top animated series of 2018 % % % % CREATED BY EXEC COEXEC PRODUCERS DEVELOPED BY PRODUCERS PRODUCERS 24 women 71 women 10 women 64 women 3 women of color 6 women of color 0 women of color 16 women of color © DR. -

SIGGRAPH Asia 2020'S Computer Animation Festival – Panel And

SIGGRAPH Asia 2020’s Computer Animation Festival – Panel and Production Talks The Making of Pixar’s Wind Jesus Martinez, Animation Manager, Pixar Animation Studios Edwin Chang, Shot Supervisor / SparkShorts Director, Wind, Pixar Animation Studios Beth Albright, Character Shading and Groom Lead, Pixar Animation Studios Join writer and director Edwin Chang, producer Jesús Martínez and supervising technical director Beth Albright as they explore the making of their heartfelt CG animated short film, Wind. Made as part of Pixar’s SparkShorts program, Wind is set in a world of magical realism where a grandmother and her grandson are trapped deep down an endless chasm, scavenging debris that surrounds them to realize their dream of escaping to a better life. A screening of the film will be followed by a “Making Of” presentation and a Q&A. Producing Over the Moon Gennie Rim, Executive Producer, Glen Keane Productions Peilin Chou, Animation Film Producer, Netflix Producers Peilin Chou and Gennie Rim discuss the development and production of the recently premiered Netflix and Pearl Studios animated musical adventure, Over the Moon, directed by the legendary Oscar winner Glen Keane, and co-directed by Oscar winner John Kahrs. In the film, a bright young girl fueled with determination and a passion for science, Fei Fei, builds a rocket ship to the moon to prove the existence of the legendary Chinese Moon Goddess, Chang’e. After an impossible journey, she ends up in a whimsical land of fantastical creatures. Directed by Keane, animated at Sony Pictures Imageworks and produced by Rim and Chou for Shanghai-based Pearl Studios, Over the Moon is a musical adventure about moving forward, embracing the unexpected, and believing the impossible is possible. -

Looking Back at the Creative Process

IATSE LOCAL 839 MAGAZINE SPRING 2020 ISSUE NO. 9 THE ANIMATION GUILD QUARTERLY SCOOBY-DOO / TESTING PRACTICES LOOKING BACK AT THE CREATIVE PROCESS SPRING 2020 “HAS ALL THE MAKINGS OF A CLASSIC.” TIME OUT NEW YORK “A GAMECHANGER”. INDIEWIRE NETFLIXGUILDS.COM KEYFRAME QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF THE ANIMATION GUILD, COVER 2 REVISION 1 NETFLIX: KLAUS PUB DATE: 01/30/20 TRIM: 8.5” X 10.875” BLEED: 8.75” X 11.125” ISSUE 09 CONTENTS 12 FRAME X FRAME 42 TRIBUTE 46 FRAME X FRAME Kickstarting a Honoring those personal project who have passed 6 FROM THE 14 AFTER HOURS 44 CALENDAR FEATURES PRESIDENT Introducing The Blanketeers 46 FINAL NOTE 20 EXPANDING THE Remembering 9 EDITOR’S FIBER UNIVERSE Disney, the man NOTE 16 THE LOCAL In Trolls World Tour, Poppy MPI primer, and her crew leave their felted Staff spotlight 11 ART & CRAFT homes to meet troll tribes Tiffany Ford’s from different regions of the color blocks kingdom in an effort to thwart Queen Barb and King Thrash from destroying all the other 28 styles of music. Hitting the road gave the filmmakers an opportunity to invent worlds from the perspective of new fabrics and fibers. 28 HIRING HUMANELY Supervisors and directors in the LA animation industry discuss hiring practices, testing, and the realities of trying to staff a show ethically. 34 ZOINKS! SCOOBY-DOO TURNS 50 20 The original series has been followed by more than a dozen rebooted series and movies, and through it all, artists and animators made sure that “those meddling kids” and a cowardly canine continued to unmask villains. -

9781474410571 Contemporary

CONTEMPORARY HOLLYWOOD ANIMATION 66543_Brown.indd543_Brown.indd i 330/09/200/09/20 66:43:43 PPMM Traditions in American Cinema Series Editors Linda Badley and R. Barton Palmer Titles in the series include: The ‘War on Terror’ and American Film: 9/11 Frames Per Second Terence McSweeney American Postfeminist Cinema: Women, Romance and Contemporary Culture Michele Schreiber In Secrecy’s Shadow: The OSS and CIA in Hollywood Cinema 1941–1979 Simon Willmetts Indie Reframed: Women’s Filmmaking and Contemporary American Independent Cinema Linda Badley, Claire Perkins and Michele Schreiber (eds) Vampires, Race and Transnational Hollywoods Dale Hudson Who’s in the Money? The Great Depression Musicals and Hollywood’s New Deal Harvey G. Cohen Engaging Dialogue: Cinematic Verbalism in American Independent Cinema Jennifer O’Meara Cold War Film Genres Homer B. Pettey (ed.) The Style of Sleaze: The American Exploitation Film, 1959–1977 Calum Waddell The Franchise Era: Managing Media in the Digital Economy James Fleury, Bryan Hikari Hartzheim, and Stephen Mamber (eds) The Stillness of Solitude: Romanticism and Contemporary American Independent Film Michelle Devereaux The Other Hollywood Renaissance Dominic Lennard, R. Barton Palmer and Murray Pomerance (eds) Contemporary Hollywood Animation: Style, Storytelling, Culture and Ideology Since the 1990s Noel Brown www.edinburghuniversitypress.com/series/tiac 66543_Brown.indd543_Brown.indd iiii 330/09/200/09/20 66:43:43 PPMM CONTEMPORARY HOLLYWOOD ANIMATION Style, Storytelling, Culture and Ideology Since the 1990s Noel Brown 66543_Brown.indd543_Brown.indd iiiiii 330/09/200/09/20 66:43:43 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. -

93Rd Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact Sheet

93RD ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS® OSCAR® NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: The Father (Sony Pictures Classics) - David Parfitt, Jean-Louis Livi and Philippe Carcassonne, producers - This is the second Best Picture nomination for David Parfitt. He won an Oscar for Shakespeare in Love (1998). This is the first nomination for both Jean-Louis Livi and Philippe Carcassonne. Judas and the Black Messiah (Warner Bros.) - Shaka King, Charles D. King and Ryan Coogler, producers - This is the first Best Picture nomination for all three. Mank (Netflix) - Ceán Chaffin, Eric Roth and Douglas Urbanski, producers - This is the third Best Picture nomination for Ceán Chaffin. Her other nominations were for The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) and The Social Network (2010). This is the first Best Picture nomination for Eric Roth. This is the second Best Picture nomination for Douglas Urbanski. His other nomination was for Darkest Hour (2017). Minari (A24) - Christina Oh, producer - This is her first nomination. Nomadland (Searchlight) - Frances McDormand, Peter Spears, Mollye Asher, Dan Janvey and Chloé Zhao, producers - This is the first Best Picture nomination for Frances McDormand, Mollye Asher and Chloé Zhao. This is the second Best Picture nomination for Peter Spears. His other nomination was for Call Me by Your Name (2017). This is the second Best Picture nomination for Dan Janvey. His other nomination was for Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012). Promising Young Woman (Focus Features) - Ben Browning, Ashley Fox, Emerald Fennell and Josey McNamara, producers - This is the first Best Picture nomination for all four. Sound of Metal (Amazon Studios) - Bert Hamelinck and Sacha Ben Harroche, producers - This is the first nomination for both.