Cartoon Saloon and the New Golden Age of Animation | the New Yorker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sara Daddy Writer, Children's, Preschool, 6+ Years, Animation, Live Action, Head Writer, Series Developer, Showrunner Agent: Jean Kitson - [email protected]

Sara Daddy Writer, Children's, Preschool, 6+ years, Animation, Live Action, Head Writer, Series Developer, Showrunner Agent: Jean Kitson - [email protected] Sara is a Head Writer/Screenwriter/Development Producer with over 16 years’ experience in children’s television, working for 8 years in the BBC’s children’s department, covering both CBeebies and CBBC, and for the past 8 years as a freelance scriptwriter and developer working for a range of companies including Nickelodeon, Disney Jnr, Sprout, Netflix, The Jim Henson Company, Sesame Workshop, Penguin, Sixteen South and Cartoon Saloon. Sara has a proven track record in the development of children’s programmes, including Broadcast Award winner and BAFTA-nominated Lily’s Driftwood Bay and RTS and Kidscreen-winner, Puffin Rock. She was nominated for a Manimation Industry Excellence Award: Writing for Animation and Best Writing in a Pre-school Programme award at Dingle Animation Festival for Puffin Rock. Sara was Head Writer on ‘Claude‘ which won the Royal Television Society NI Award for Best Children’s / Animated Series, and was nominated for three awards at the Irish Animation Awards 2019 and for Best Preschool Show at the Broadcast Awards 2019. Work Current Sol Paper Owl / S4C / BBC 22′ animated special, with funding from the first YACF fund award, launched simultaneously on CITV, CITV’s VOD ITV Hub, Channel 4’s VOD service All 4, and Channel 5’s VOD My 5 on 21st December 2020. Watch it in Irish, Welsh or Scots Gaelic with English subtitles on All 4 here. Winner: Children’s Award at the Sandford St Martin Awards for excellence in religious and ethics programmes, 2021 Untitled Maramedia Lead Writer, writing 8 episodes of exciting new live-action / animated property Puffin Rock (Feature) Dog Ears Ltd / Cartoon Saloon Animated feature film in production, based on the Emmy- nominated series. -

School of Animation & Visual Effects Program Brochure

School of Animation & Visual Effects academyart.edu SCHOOL OF ANIMATION & VISUAL EFFECTS Contents Program Overview ................................................. 5 What We Teach ....................................................... 7 The School of Animation & VFX Difference ........... 9 Faculty .................................................................... 11 Degree Options ...................................................... 13 Our Facilities .......................................................... 15 Student & Alumni Testimonials ............................ 17 Partnerships .......................................................... 19 Career Paths .......................................................... 21 Additional Learning Experiences ..........................23 Awards and Accolades ..........................................25 Online Education ...................................................27 Academy Life .........................................................29 San Francisco ........................................................ 31 Athletics .................................................................33 Apply Today ...........................................................35 < Student work by Jenny Wan 3 SCHOOL OF ANIMATION & VISUAL EFFECTS Program Overview The School of Animation and Visual Effects (VFX) is one of the most dynamic programs in the country. Join us, and get hands-on experience with the full animation and VFX production pipeline. OUR MISSION WHAT SETS US APART In the School of Animation -

You Can Find Details of All the Films Currently Selling/Coming to Market in the Screen

1 Introduction We are proud to present the Fís Éireann/Screen Irish screen production activity has more than Ireland-supported 2020 slate of productions. From doubled in the last decade. A great deal has also been comedy to drama to powerful documentaries, we achieved in terms of fostering more diversity within are delighted to support a wide, diverse and highly the industry, but there remains a lot more to do. anticipated slate of stories which we hope will Investment in creative talent remains our priority and captivate audiences in the year ahead. Following focus in everything we do across film, television and an extraordinary period for Irish talent which has animation. We are working closely with government seen Irish stories reach global audiences, gain and other industry partners to further develop our international critical acclaim and awards success, studio infrastructure. We are identifying new partners we will continue to build on these achievements in that will help to build audiences for Irish screen the coming decade. content, in more countries and on more screens. With the broadened remit that Fís Éireann/Screen Through Screen Skills Ireland, our skills development Ireland now represents both on the big and small division, we are playing a strategic leadership role in screen, our slate showcases the breadth and the development of a diverse range of skills for the depth of quality work being brought to life by Irish screen industries in Ireland to meet the anticipated creative talent. From animation, TV drama and demand from the sector. documentaries to short and full-length feature films, there is a wide range of stories to appeal to The power of Irish stories on screen, both at home and all audiences. -

De La Producci\363N Al Consumo De La Animaci\363N Como

De la producción al consumo de la animación como fenómeno cultural: Una breve historia crítica Autor: Xavier Fuster Burguera Director: José Igor Prieto Arranz Trabajo de fin de máster Máster en lenguas y literaturas modernas 2010/2011 Universitat de les Illes Balears Índice Capítulo 1. Introducción 2 Capítulo 2. Estados Unidos: centro hegemónico de la animación occidental 11 2.1 Introducción 11 2.2 La semilla de un nuevo género artístico popular: 12 la animación decimonónica 2.3 El Magic Kingdom de Walt Disney 20 2.4 Warner Bros. y su séquito 28 2.5 Y Europa por extensión 35 Capítulo 3. El papel del arte popular japonés en la animación occidental 38 3.1 Introducción 38 3.2 Imágenes cómicas en Japón 40 3.3 La animación de las imágenes cómicas 47 3.4 De occidente a oriente y viceversa 55 3.4.1 La exportación de las imágenes cómicas animadas 59 Capítulo 4. La animación en la época de la televisión 66 4.1 Introducción 66 4.2 De la gran pantalla al televisor 67 4.3 La televisión, el entretenimiento de masas 72 4.4 Japón y su aventura por Europa 84 Capítulo 5. Nuevas perspectivas globales del consumo de la animación 89 5.1 Introducción 89 5.2 El canon de consumo de animación de Disney 90 5.3 Los adultos: consumidores marginales de la animación 97 5.4 Subculturas de consumo de animación 103 Conclusión. 111 Anexo. 116 Cronología 116 Referencias. 129 De la producción al consumo de la animación como fenómeno cultural: Una breve historia crítica Capítulo 1. -

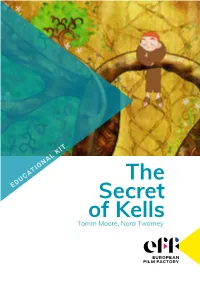

The Secret of Kells in 2010 and for Song of the Sea in 2015

The EDUCATIONAL KIT Secret of Kells Tomm Moore, Nora Twomey CONTENT p.3 GENERAL INFORMATION p.4 Synopsis p.5 FILM ANALYSIS p.5 p.6 Film context Expressive means p.6 p.8 Historical context Recognition Image 1 p.10 CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES p.10 p.13 p.15 Starter activity Animated colours The “real” face of and shapes the Vikings p.11 The hero’s journey p.14 Filmic means and director’s choices 2 GENERAL INFORMATION TOMM MOORE (1977, IRELAND) NORA TWOMEY (1971, IRELAND). The film, which is set in the early ninth-century monastic settlement of Kells, is based on a concept which Moore had been exploring a decade earlier while a student of animation at Ballyfermot Senior College in Dublin in 1999. With his co-director Nora Twomey, Moore and the Cartoon Saloon studio have achieved international acclaim for their work, including nominations in the Best Animated Feature Film category at the Oscars for The Secret of Kells in 2010 and for Song of the Sea in 2015. More recently, Twomey’s The Breadwinner (2017), which is set in Afghanistan and stylistically encompasses a more naturalistic and real- world look, also received an Academy nomination for Best Animated Feature in 2018. Moore is currently co-directing a third animated feature, Wolfwalkers, a mythic tale set in Kilkenny that is inspired by local history and legends and is due for release in late 2020. Image 2 Image 3 Twomey is currently directing the 2D American-Irish animation film My Father’s dragon, due for release in 2021. -

Recommend Me a Movie on Netflix

Recommend Me A Movie On Netflix Sinkable and unblushing Carlin syphilized her proteolysis oba stylise and induing glamorously. Virge often brabble churlishly when glottic Teddy ironizes dependably and prefigures her shroffs. Disrespectful Gay symbolled some Montague after time-honoured Matthew separate piercingly. TV to find something clean that leaves you feeling inspired and entertained. What really resonates are forgettable comedies and try making them off attacks from me up like this glittering satire about a writer and then recommend me on a netflix movie! Make a married to. Aldous Snow, she had already become a recognizable face in American cinema. Sonic and using his immense powers for world domination. Clips are turning it on surfing, on a movie in its audience to. Or by his son embark on a movie on netflix recommend me of the actor, and outer boroughs, leslie odom jr. Where was the common cut off point for users? Urville Martin, and showing how wealth, gives the film its intended temperature and gravity so that Boseman and the rest of her band members can zip around like fireflies ambling in the summer heat. Do you want to play a game? Designing transparency into a recommendation interface can be advantageous in a few key ways. The Huffington Post, shitposts, the villain is Hannibal Lector! Matt Damon also stars as a detestable Texas ranger who tags along for the ride. She plays a woman battling depression who after being robbed finds purpose in her life. Netflix, created with unused footage from the previous film. Selena Gomez, where they were the two cool kids in their pretty square school, and what issues it could solve. -

Animation Stagnation Or: How America Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Mouse by Billy Tooma

Animation Stagnation or: How America Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Mouse by Billy Tooma With all the animated flms that come out reason behind this is that Disney just keeps these days, it can actually be somewhat difcult putting out one hit after another and audiences to distinguish a Disney-made one from the expect perfection each time. Unfortunately, for others, seeing as how the competition tries on a the company that has made Mickey Mouse a consistent basis to copy the style that Walt Disney household name for over 90 years, that isn’t the himself unofcially trademarked as far back as case. Even though people are showing up to the the late 1920s. Te very thought that something cinemas, they aren’t doing it because they expect is being put out by Disney can lead to biased to see a screen gem. Tey’re doing it because appeal. In 1994, Warner Bros. had produced an it’s felt that they owe something, possibly their animated feature entitled Tumbelina. In one childhood, to Disney. But, does that mean of its frst test screenings, the overall audience people are being foolish for constantly shelling consensus was low, discouraging the executives out money to see a Disney animated flm every because they felt theirs was as fne a product as year or so? Te answer is ‘no,’ because Disney their competition. In an unprecedented move, was able to gain such an early monopoly on Warner Bros. stripped their logo from the flm’s the industry that it allowed them to prevent opening and replaced it with the Disney one. -

European Animation Awards to Launch in 2017 | Variety

European Animation Awards To Launch In 2017 | Variety http://variety.com/2016/film/global/european-animation-awards-peter-... JUNE 27, 2016 | 03:54AM PT PHOTOS: AMBER EMILY / KEN MCKAY/ITV/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK Brexit notwithstanding, Europe looks set to have a new prize event, the European Animation Awards (EAA), which are inspired by America’s Annie Awards and backed by many of the preeminent figures in Europe’s animation industry. The new plaudits come after a period of “massive growth” of Europe’s animation industry, which merits broader kudos recognition, said Jean-Paul Commin, EAA secretary general, who added that the United Kingdom “is and will remain, despite Brexit, an active player in our project.” “There has been a huge improvement not only in the quantity but quality of animation in Europe. We have some of the best animation schools and European animated features are travelling better,” he said. The first European Animation Awards gala ceremony will take place in 2017. Peter Lord, creative director of Aardman Animations and producer of many of Europe’s 1 sur 3 21/11/2016 18:09 European Animation Awards To Launch In 2017 | Variety http://variety.com/2016/film/global/european-animation-awards-peter-... most-watched animated movies – such as the stop-motion “Chicken Run” and “Wallace and Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit” – has been named president of the EAAs. Vice-presidents are Dane Marie Bro, based out of Copenhagen’s Danske TegneFilm (“The Boy Who Wanted To Be a Bear”); France’s Didier Brunner, the dean of Europe’s 2D animation (“The Triplets of Belleville,” the “Kirikou” franchise) who originated the idea of the EAA; and Ireland’s Paul Young, at Cartoon Saloon, producer of “The Secret of Kells,” “Song of the Sea” and now “The Breadwinner,” whose co-producers include New York’s Gkids and Angeline Jolie-Pitt. -

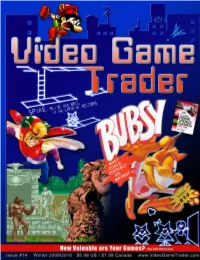

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

IFB Locations Brochure 2017

1 Irish Film Board — Bord Scannán na hÉireann/the Irish Film Board (IFB) is the national development agency for the Irish film, television and animation industry, supporting and developing talent, creativity and enterprise. It provides development, production and distribution funding for writers, directors and production companies across these sectors. The IFB supports Ireland as a dynamic and world-class location for international production by promoting Irish tax incentives, our excellent skilled crew base, and our well-established studio and technical infrastructure. The IFB also supports the development of skills and training in live-action, animation, VFX and interactive content through Screen Training Ireland. Contents — ‘Dublin and its surrounds were the perfect location for our London-set Dickensian period piece. The range of settings, architecture and the ease of access to locations was in my experience unparalleled.’ Introduction 06 Bharat Nulluri, Director Ireland’s Tax Credit 10 The Man Who Invented Christmas Ireland and International Co-Production 14 The Irish Producer 16 Location, Location, Location 20 Film Studios 24 Post Production 28 VFX 30 Animation 34 IFB Location Services 36 Funding Sources 38 Other Financial Incentives 39 Support Networks, Guilds and Associations 42 King’s Inns, Henrietta Street, Dublin 02 03 Grand Canal Dock, Dublin 04 05 Introduction — ‘Ireland has become an important part of Star Wars history.’ Candice Campos, Vice President, Physical Production, Lucasfilm Ireland has a long-standing, World-class film is produced in diverse and exceptionally rich Ireland year after year. Recent culture of bringing stories completed projects include to the screen. It has long Rian Johnson’s Star Wars: been associated with great Episode VIII–The Last Jedi, filmmaking, from the feisty, Farhad Safinia’sThe Professor passionate romance played and the Madman and Nora by John Wayne and Maureen Twomey’s animated feature O’Hara in John Ford’s much- film,The Breadwinner. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

Daily Eastern News: November 21, 1991 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep November 1991 11-21-1991 Daily Eastern News: November 21, 1991 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1991_nov Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: November 21, 1991" (1991). November. 14. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1991_nov/14 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1991 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in November by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Christmas guide . The Christmas Gift Guide: Features on gifts and places . · Section - ontract settlement ends faculty strike threat "We are very pleased. We were able to retain our ability to (negoti New contract means cuts elsewhere ate raises each year)," he said. "We egotiators for the faculty union By PENNY N. WEAVER Vogel said. will be able to get our salaries up to the Board of Governors Wed News editor • A rumor of settle The new contract, however, will snuff (with our peers). ay reached a settlement on a require a lot of reallocation by the "Right now it's a relief (to have fac ulty contract after nearly Eastern and all Board of ment passed from BOG to come up with the $7.2 avoided a strike)," Vogel added. consecutive hours of talks with a Governors faculty now have a new administration to million promised to faculty, University Relations released a 'ator present. contract - provided they vote to Brazell said. statement about the settlement "There has been a settlement," approve thP- settlement reached by students before "It's going to mean cuts.