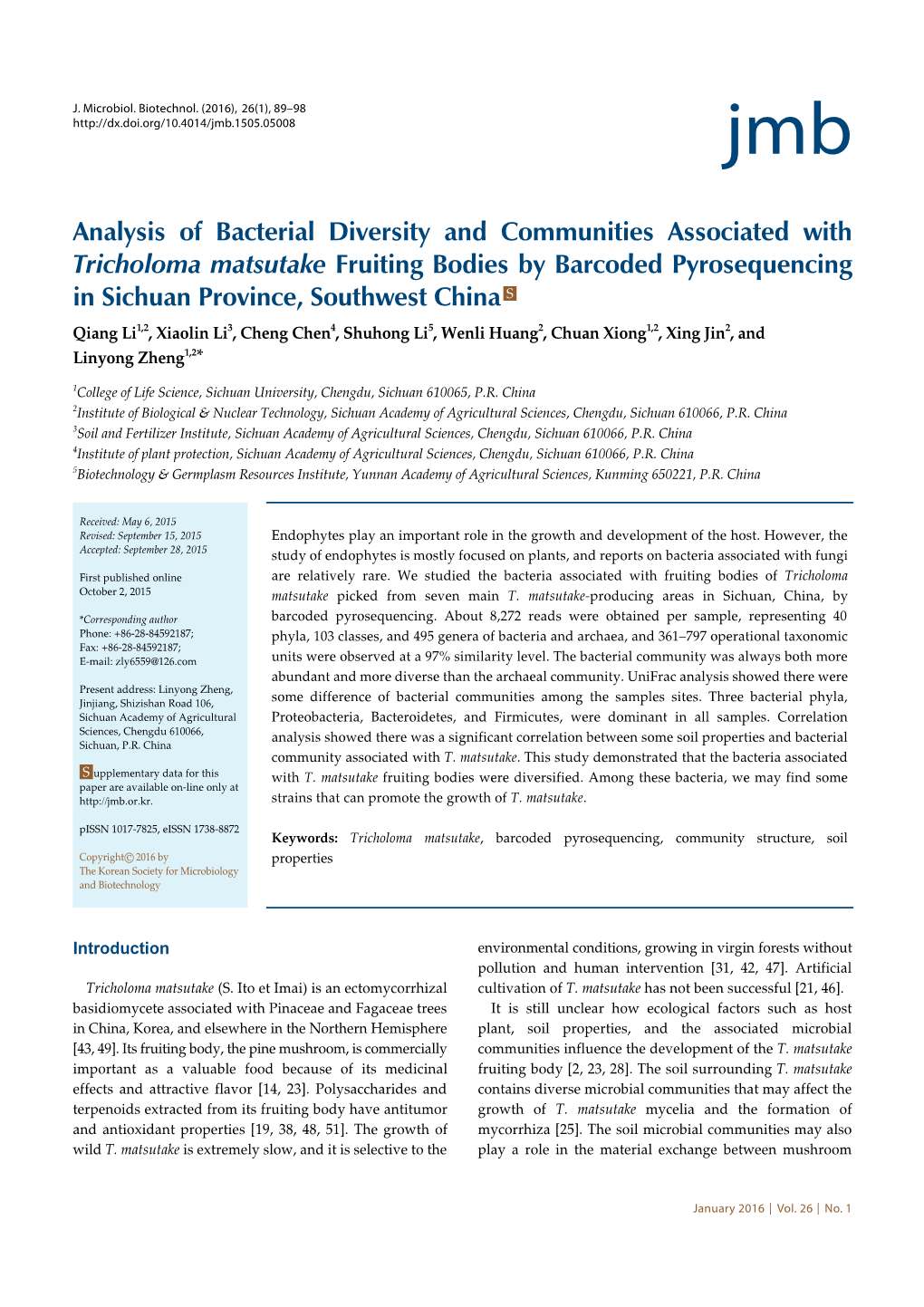

Analysis of Bacterial Diversity and Communities Associated With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatio-Temporal Study of Microbiology in the Stratified Oxic-Hypoxic-Euxinic, Freshwater- To-Hypersaline Ursu Lake

Spatio-temporal insights into microbiology of the freshwater-to- hypersaline, oxic-hypoxic-euxinic waters of Ursu Lake Baricz, A., Chiriac, C. M., Andrei, A-., Bulzu, P-A., Levei, E. A., Cadar, O., Battes, K. P., Cîmpean, M., enila, M., Cristea, A., Muntean, V., Alexe, M., Coman, C., Szekeres, E. K., Sicora, C. I., Ionescu, A., Blain, D., O’Neill, W. K., Edwards, J., ... Banciu, H. L. (2020). Spatio-temporal insights into microbiology of the freshwater-to- hypersaline, oxic-hypoxic-euxinic waters of Ursu Lake. Environmental Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.14909, https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.14909 Published in: Environmental Microbiology Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2019 Wiley. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. -

Novel Bacterial Lineages Associated with Boreal Moss Species Hannah

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/219659; this version posted November 16, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Novel bacterial lineages associated with boreal moss species 2 Hannah Holland-Moritz1,2*, Julia Stuart3, Lily R. Lewis4, Samantha Miller3, Michelle C. Mack3, Stuart 3 F. McDaniel4, Noah Fierer1,2* 4 Affiliations: 5 1Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado at Boulder, 6 Boulder, CO, USA 7 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, CO, 8 USA 9 3Center for Ecosystem Science and Society, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ USA 10 4Department of Biology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611-8525, USA 11 *Corresponding Author 12 13 Abstract 14 Mosses are critical components of boreal ecosystems where they typically account for a large 15 proportion of net primary productivity and harbor diverse bacterial communities that can be the major 16 source of biologically-fixed nitrogen in these ecosystems. Despite their ecological importance, we have 17 limited understanding of how microbial communities vary across boreal moss species and the extent to 18 which local environmental conditions may influence the composition of these bacterial communities. 19 We used marker gene sequencing to analyze bacterial communities associated with eight boreal moss 20 species collected near Fairbanks, AK USA. We found that host identity was more important than site in 21 determining bacterial community composition and that mosses harbor diverse lineages of potential N2- 22 fixers as well as an abundance of novel taxa assigned to understudied bacterial phyla (including 23 candidate phylum WPS-2). -

Microbiology of Endodontic Infections

Scient Open Journal of Dental and Oral Health Access Exploring the World of Science ISSN: 2369-4475 Short Communication Microbiology of Endodontic Infections This article was published in the following Scient Open Access Journal: Journal of Dental and Oral Health Received August 30, 2016; Accepted September 05, 2016; Published September 12, 2016 Harpreet Singh* Abstract Department of Conservative Dentistry & Endodontics, Gian Sagar Dental College, Patiala, Punjab, India Root canal system acts as a ‘privileged sanctuary’ for the growth and survival of endodontic microbiota. This is attributed to the special environment which the microbes get inside the root canals and several other associated factors. Although a variety of microbes have been isolated from the root canal system, bacteria are the most common ones found to be associated with Endodontic infections. This article gives an in-depth view of the microbiology involved in endodontic infections during its different stages. Keywords: Bacteria, Endodontic, Infection, Microbiology Introduction Microorganisms play an unequivocal role in infecting root canal system. Endodontic infections are different from the other oral infections in the fact that they occur in an environment which is closed to begin with since the root canal system is an enclosed one, surrounded by hard tissues all around [1,2]. Most of the diseases of dental pulp and periradicular tissues are associated with microorganisms [3]. Endodontic infections occur and progress when the root canal system gets exposed to the oral environment by one reason or the other and simultaneously when there is fall in the body’s immune when the ingress is from a carious lesion or a traumatic injury to the coronal tooth structure.response [4].However, To begin the with, issue the if notmicrobes taken arecare confined of, ultimately to the leadsintra-radicular to the egress region of pathogensIn total, and bacteria their by-productsdetected from from the the oral apical cavity foramen fall into to 13 the separate periradicular phyla, tissues. -

Proposal of Mycetocola Gen. Nov. in the Family Microbacteriaceae and Three New Species, Mycetocola Saprophilus Sp

International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2001), 51, 937–944 Printed in Great Britain Proposal of Mycetocola gen. nov. in the family Microbacteriaceae and three new species, Mycetocola saprophilus sp. nov., Mycetocola tolaasinivorans sp. nov. and Mycetocola lacteus sp. nov., isolated from cultivated mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus 1 National Institute of Takanori Tsukamoto,1† Mariko Takeuchi,2 Osamu Shida,3 Hitoshi Murata4 Sericultural and 1 Entomological Sciences, and Akira Shirata Ohwashi 1-2, Tsukuba 305-8634, Japan Author for correspondence: Takanori Tsukamoto. Tel: 81 45 211 7153. Fax: 81 45 211 0611. 2 j j Institute for Fermentation, e-mail: taktak!air.linkclub.or.jp Osaka, 17-85, Juso- honmachi 2-chome, Yodogawa-ku, Osaka 532-8686, Japan The taxonomic positions of 10 tolaasin-detoxifying bacteria, which were isolated from the cultivated mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus, were investigated. 3 R&D Department, Higeta Shoyu Co. Ltd, Choshi, These strains are Gram-positive, obligately aerobic, non-sporulating and Chiba 288-8680, Japan irregular rod-shaped bacteria. They have the following characteristics: the 4 Forestry and Forest major menaquinone is MK-10, the DNA GMC content ranges from 64 to Products Research 65 mol%, the diamino acid in the cell wall is lysine and the muramic acid in Institute, PO Box 16, the peptidoglycan is an acetyl type. The major fatty acids are anteiso-C Tsukuba-Norin, 305-8687, 15:0 Japan and anteiso-C17:0. On the basis of morphological, physiological and chemotaxonomic characteristics, together with DNA–DNA reassociation values and 16S rRNA gene sequence comparison data, the new genus Mycetocola gen. -

Alpine Soil Bacterial Community and Environmental Filters Bahar Shahnavaz

Alpine soil bacterial community and environmental filters Bahar Shahnavaz To cite this version: Bahar Shahnavaz. Alpine soil bacterial community and environmental filters. Other [q-bio.OT]. Université Joseph-Fourier - Grenoble I, 2009. English. tel-00515414 HAL Id: tel-00515414 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00515414 Submitted on 6 Sep 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE Pour l’obtention du titre de l'Université Joseph-Fourier - Grenoble 1 École Doctorale : Chimie et Sciences du Vivant Spécialité : Biodiversité, Écologie, Environnement Communautés bactériennes de sols alpins et filtres environnementaux Par Bahar SHAHNAVAZ Soutenue devant jury le 25 Septembre 2009 Composition du jury Dr. Thierry HEULIN Rapporteur Dr. Christian JEANTHON Rapporteur Dr. Sylvie NAZARET Examinateur Dr. Jean MARTIN Examinateur Dr. Yves JOUANNEAU Président du jury Dr. Roberto GEREMIA Directeur de thèse Thèse préparée au sien du Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine (LECA, UMR UJF- CNRS 5553) THÈSE Pour l’obtention du titre de Docteur de l’Université de Grenoble École Doctorale : Chimie et Sciences du Vivant Spécialité : Biodiversité, Écologie, Environnement Communautés bactériennes de sols alpins et filtres environnementaux Bahar SHAHNAVAZ Directeur : Roberto GEREMIA Soutenue devant jury le 25 Septembre 2009 Composition du jury Dr. -

NC10 Phylum Anaerobs? Methanotrophs? Where Can I Find Them?

NC10 phylum Anaerobs? Methanotrophs? Where can I find them? Beate Kraft Microbial Diversity 2012 Abstract Methylomirabilis oxyfera, the only cultured member of the NC10 phylum performs the newly discovered pathway of NO-dismutation. In this study different habitats were screened for the presence of member of this phylum and the diversity of the sequences obtained was analyzed. Furthermore enrichment cultures for nitrite reduction coupled to methane oxidation were set up. Indeed, the presence of NC10 seems to be associated with nitrite and methane rich fresh water environments. Introduction Recently a new nitrite reduction pathway, NO-dismutation, coupled to methane oxidation has been discovered (Ettwig et al. 2010). In NO-dismutation nitrite is oxidized to NO as in denitrification but then NO dimutated into N2 and O2 instead of being further reduced to N2O. The generated oxygen is then used for methane oxidation. The organism responsible for this process is Methylomirabils oxfera. It is the only cultured member of the candidate phylum NC10. Fig 1: Pathway of NO-dismutation (from Ettwig et al. 2010) It remains open if other members of the NC10 phylum share the same metabolism and respiratory pathway or if they are metabolically more diverse. 16S sequences that fall into the NC10 phylum have been found in mainly oxygen limited freshwater habitats such as lakes including lake sediments, rice paddy soils, wastewater sludge and ditches (Deutzmann and Schink 2011, Luesken et a.l 2011). Their occurrence apparently seem to be correlated with the presence of methane and nitrite in the habitat. This would suggest a similar respiratory pathway as in Methylomirabilis oxyfera. -

Yu-Chen Ling and John W. Moreau

Microbial Distribution and Activity in a Coastal Acid Sulfate Soil System Introduction: Bioremediation in Yu-Chen Ling and John W. Moreau coastal acid sulfate soil systems Method A Coastal acid sulfate soil (CASS) systems were School of Earth Sciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia formed when people drained the coastal area Microbial distribution controlled by environmental parameters Microbial activity showed two patterns exposing the soil to the air. Drainage makes iron Microbial structures can be grouped into three zones based on the highest similarity between samples (Fig. 4). Abundant populations, such as Deltaproteobacteria, kept constant activity across tidal cycling, whereas rare sulfides oxidize and release acidity to the These three zones were consistent with their geological background (Fig. 5). Zone 1: Organic horizon, had the populations changed activity response to environmental variations. Activity = cDNA/DNA environment, low pH pore water further dissolved lowest pH value. Zone 2: surface tidal zone, was influenced the most by tidal activity. Zone 3: Sulfuric zone, Abundant populations: the heavy metals. The acidity and toxic metals then Method A Deltaproteobacteria Deltaproteobacteria this area got neutralized the most. contaminate coastal and nearby ecosystems and Method B 1.5 cause environmental problems, such as fish kills, 1.5 decreased rice yields, release of greenhouse gases, Chloroflexi and construction damage. In Australia, there is Gammaproteobacteria Gammaproteobacteria about a $10 billion “legacy” from acid sulfate soils, Chloroflexi even though Australia is only occupied by around 1.0 1.0 Cyanobacteria,@ Acidobacteria Acidobacteria Alphaproteobacteria 18% of the global acid sulfate soils. Chloroplast Zetaproteobacteria Rare populations: Alphaproteobacteria Method A log(RNA(%)+1) Zetaproteobacteria log(RNA(%)+1) Method C Method B 0.5 0.5 Cyanobacteria,@ Bacteroidetes Chloroplast Firmicutes Firmicutes Bacteroidetes Planctomycetes Planctomycetes Ac8nobacteria Fig. -

Table S5. the Information of the Bacteria Annotated in the Soil Community at Species Level

Table S5. The information of the bacteria annotated in the soil community at species level No. Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species The number of contigs Abundance(%) 1 Firmicutes Bacilli Bacillales Bacillaceae Bacillus Bacillus cereus 1749 5.145782459 2 Bacteroidetes Cytophagia Cytophagales Hymenobacteraceae Hymenobacter Hymenobacter sedentarius 1538 4.52499338 3 Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadales Gemmatimonadaceae Gemmatirosa Gemmatirosa kalamazoonesis 1020 3.000970902 4 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas indica 797 2.344876284 5 Firmicutes Bacilli Lactobacillales Streptococcaceae Lactococcus Lactococcus piscium 542 1.594633558 6 Actinobacteria Thermoleophilia Solirubrobacterales Conexibacteraceae Conexibacter Conexibacter woesei 471 1.385742446 7 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas taxi 430 1.265115184 8 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas wittichii 388 1.141545794 9 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas sp. FARSPH 298 0.876754244 10 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sorangium cellulosum 260 0.764953367 11 Proteobacteria Deltaproteobacteria Myxococcales Polyangiaceae Sorangium Sphingomonas sp. Cra20 260 0.764953367 12 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas panacis 252 0.741416341 -

Bacteria Clostridia Bacilli Eukaryota CFB Group

AM935842.1.1361 uncultured Burkholderiales bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AY283260.1.1552 Alcaligenes sp. PCNB−2 Class Betaproteobacteria AM934953.1.1374 uncultured Burkholderiales bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AJ581593.1.1460 uncultured betaAM936569.1.1351 proteobacterium uncultured Class Betaproteobacteria Derxia sp. Class Betaproteobacteria AJ581621.1.1418 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria DQ248272.1.1498 uncultured soil bacterium soil uncultured DQ248272.1.1498 DQ248235.1.1498 uncultured soil bacterium RS49 DQ248270.1.1496 uncultured soil bacterium DQ256489.1.1211 Variovorax paradoxus Class Betaproteobacteria Class paradoxus Variovorax DQ256489.1.1211 AF523053.1.1486 uncultured Comamonadaceae bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AY706442.1.1396 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY706442.1.1396 AJ536763.1.1422 uncultured bacterium CS000359.1.1530 Variovorax paradoxus Class Betaproteobacteria Class paradoxus Variovorax CS000359.1.1530 AY168733.1.1411 uncultured bacterium AJ009470.1.1526 uncultured bacterium SJA−62 Class Betaproteobacteria Class SJA−62 bacterium uncultured AJ009470.1.1526 AY212561.1.1433 uncultured bacterium D16212.1.1457 Rhodoferax fermentans Class Betaproteobacteria Class fermentans Rhodoferax D16212.1.1457 AY957894.1.1546 uncultured bacterium AJ581620.1.1452 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria RS76 AY625146.1.1498 uncultured bacterium RS65 DQ316832.1.1269 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria DQ404909.1.1513 uncultured bacterium uncultured DQ404909.1.1513 AB021341.1.1466 bacterium rM6 AJ487020.1.1500 uncultured bacterium uncultured AJ487020.1.1500 RS7 RS86RC AF364862.1.1425 bacterium BA128 Class Betaproteobacteria AY957931.1.1529 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957931.1.1529 CP000884.723807.725332 Delftia acidovorans SPH−1 Class Betaproteobacteria AY957923.1.1520 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957923.1.1520 RS18 AY957918.1.1527 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957918.1.1527 AY945883.1.1500 uncultured bacterium AF526940.1.1489 uncultured Ralstonia sp. -

The Phylogenetic Composition and Structure of Soil Microbial Communities Shifts in Response to Elevated Carbon Dioxide

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy The ISME Journal (2012) 6, 259–272 & 2012 International Society for Microbial Ecology All rights reserved 1751-7362/12 www.nature.com/ismej ORIGINAL ARTICLE The phylogenetic composition and structure of soil microbial communities shifts in response to elevated carbon dioxide Zhili He1, Yvette Piceno2, Ye Deng1, Meiying Xu1,3, Zhenmei Lu1,4, Todd DeSantis2, Gary Andersen2, Sarah E Hobbie5, Peter B Reich6 and Jizhong Zhou1,2 1Institute for Environmental Genomics, Department of Botany and Microbiology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA; 2Ecology Department, Earth Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA; 3Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Microbial Culture Collection and Application, Guangdong Institute of Microbiology, Guangzhou, China; 4College of Life Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China; 5Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior, St Paul, MN, USA and 6Department of Forest Resources, University of Minnesota, St Paul, MN, USA One of the major factors associated with global change is the ever-increasing concentration of atmospheric CO2. Although the stimulating effects of elevated CO2 (eCO2) on plant growth and primary productivity have been established, its impacts on the diversity and function of soil microbial communities are poorly understood. In this study, phylogenetic microarrays (PhyloChip) were used to comprehensively survey the richness, composition and structure of soil microbial communities in a grassland experiment subjected to two CO2 conditions (ambient, 368 p.p.m., versus elevated, 560 p.p.m.) for 10 years. The richness based on the detected number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) significantly decreased under eCO2. -

Cell Structure and Function in the Bacteria and Archaea

4 Chapter Preview and Key Concepts 4.1 1.1 DiversityThe Beginnings among theof Microbiology Bacteria and Archaea 1.1. •The BacteriaThe are discovery classified of microorganismsinto several Cell Structure wasmajor dependent phyla. on observations made with 2. theThe microscope Archaea are currently classified into two 2. •major phyla.The emergence of experimental 4.2 Cellscience Shapes provided and Arrangements a means to test long held and Function beliefs and resolve controversies 3. Many bacterial cells have a rod, spherical, or 3. MicroInquiryspiral shape and1: Experimentation are organized into and a specific Scientificellular c arrangement. Inquiry in the Bacteria 4.31.2 AnMicroorganisms Overview to Bacterialand Disease and Transmission Archaeal 4.Cell • StructureEarly epidemiology studies suggested how diseases could be spread and 4. Bacterial and archaeal cells are organized at be controlled the cellular and molecular levels. 5. • Resistance to a disease can come and Archaea 4.4 External Cell Structures from exposure to and recovery from a mild 5.form Pili allowof (or cells a very to attach similar) to surfacesdisease or other cells. 1.3 The Classical Golden Age of Microbiology 6. Flagella provide motility. Our planet has always been in the “Age of Bacteria,” ever since the first 6. (1854-1914) 7. A glycocalyx protects against desiccation, fossils—bacteria of course—were entombed in rocks more than 3 billion 7. • The germ theory was based on the attaches cells to surfaces, and helps observations that different microorganisms years ago. On any possible, reasonable criterion, bacteria are—and always pathogens evade the immune system. have been—the dominant forms of life on Earth. -

Sepf Is the Ftsz Anchor in Archaea, with Features of an Ancestral Cell Division System

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23099-8 OPEN SepF is the FtsZ anchor in archaea, with features of an ancestral cell division system Nika Pende1,8, Adrià Sogues2,8, Daniela Megrian1,3, Anna Sartori-Rupp4, Patrick England 5, Hayk Palabikyan6, ✉ Simon K.-M. R. Rittmann 6, Martín Graña 7, Anne Marie Wehenkel 2 , Pedro M. Alzari 2 & ✉ Simonetta Gribaldo 1 Most archaea divide by binary fission using an FtsZ-based system similar to that of bacteria, 1234567890():,; but they lack many of the divisome components described in model bacterial organisms. Notably, among the multiple factors that tether FtsZ to the membrane during bacterial cell constriction, archaea only possess SepF-like homologs. Here, we combine structural, cellular, and evolutionary analyses to demonstrate that SepF is the FtsZ anchor in the human-associated archaeon Methanobrevibacter smithii. 3D super-resolution microscopy and quantitative analysis of immunolabeled cells show that SepF transiently co-localizes with FtsZ at the septum and possibly primes the future division plane. M. smithii SepF binds to membranes and to FtsZ, inducing filament bundling. High-resolution crystal structures of archaeal SepF alone and in complex with the FtsZ C-terminal domain (FtsZCTD) reveal that SepF forms a dimer with a homodimerization interface driving a binding mode that is different from that previously reported in bacteria. Phylogenetic analyses of SepF and FtsZ from bacteria and archaea indicate that the two proteins may date back to the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA), and we speculate that the archaeal mode of SepF/FtsZ interaction might reflect an ancestral feature. Our results provide insights into the mechanisms of archaeal cell division and pave the way for a better understanding of the processes underlying the divide between the two prokaryotic domains.