Perspectives from Urban and Rural Contexts in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usaid's Malaria Action Program for Districts

USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS GENDER ANALYSIS MAY 2017 Contract No.: AID-617-C-160001 June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis i USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS Gender Analysis May 2017 Contract No.: AID-617-C-160001 Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis ii DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government. June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis iii Table of Contents ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... VIII 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 2. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................1 COUNTRY CONTEXT ...................................................................................................................3 USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS .................................................................6 STUDY DESCRIPTION..................................................................................................................6 -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

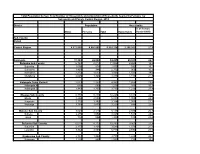

Population by Parish

Total Population by Sex, Total Number of Households and proportion of Households headed by Females by Subcounty and Parish, Central Region, 2014 District Population Households % of Female Males Females Total Households Headed HHS Sub-County Parish Central Region 4,672,658 4,856,580 9,529,238 2,298,942 27.5 Kalangala 31,349 22,944 54,293 20,041 22.7 Bujumba Sub County 6,743 4,813 11,556 4,453 19.3 Bujumba 1,096 874 1,970 592 19.1 Bunyama 1,428 944 2,372 962 16.2 Bwendero 2,214 1,627 3,841 1,586 19.0 Mulabana 2,005 1,368 3,373 1,313 21.9 Kalangala Town Council 2,623 2,357 4,980 1,604 29.4 Kalangala A 680 590 1,270 385 35.8 Kalangala B 1,943 1,767 3,710 1,219 27.4 Mugoye Sub County 6,777 5,447 12,224 3,811 23.9 Bbeta 3,246 2,585 5,831 1,909 24.9 Kagulube 1,772 1,392 3,164 1,003 23.3 Kayunga 1,759 1,470 3,229 899 22.6 Bubeke Sub County 3,023 2,110 5,133 2,036 26.7 Bubeke 2,275 1,554 3,829 1,518 28.0 Jaana 748 556 1,304 518 23.0 Bufumira Sub County 6,019 4,273 10,292 3,967 22.8 Bufumira 2,177 1,404 3,581 1,373 21.4 Lulamba 3,842 2,869 6,711 2,594 23.5 Kyamuswa Sub County 2,733 1,998 4,731 1,820 20.3 Buwanga 1,226 865 2,091 770 19.5 Buzingo 1,507 1,133 2,640 1,050 20.9 Maziga Sub County 3,431 1,946 5,377 2,350 20.8 Buggala 2,190 1,228 3,418 1,484 21.4 Butulume 1,241 718 1,959 866 19.9 Kampala District 712,762 794,318 1,507,080 414,406 30.3 Central Division 37,435 37,733 75,168 23,142 32.7 Bukesa 4,326 4,711 9,037 2,809 37.0 Civic Centre 224 151 375 161 14.9 Industrial Area 383 262 645 259 13.9 Kagugube 2,983 3,246 6,229 2,608 42.7 Kamwokya -

FY 2020/21 Vote:600 Bukomansimbi District

LG Approved Workplan Vote:600 Bukomansimbi District FY 2020/21 Foreword We are pleased to present our Draft Performance Contract for the Financial year 2020.2021.This is in line with the relevant laws including the Constitution, Local Government Act, and the Public Finance and Management Act. Going forward we acknowledge the Contribution of the Ministries, Departments and agencies that have supported us since the birth of this District Local Government. Special thanks also go to Development Partners namely Korea Foundation for International Development for their enormous contribution to our Health sector in the Emergency and Obstetrics Care. Rakai School of Health Sciences for their Contribution towards mitigation of HIV/AIDS. GAVI, WHO, UNICEF, Dutch Council, and TASO; to you we say thank you. Towards the end of March,2020, the country and this District were caught unaware with the Deadly Corvid 19 Virus, the Floods that resulted from heavy rains, which destroyed peoples property. Although so far we have not yet registered a single positive case in the District, we should not tire to keep alert, continue with the surveillance, educate the massses (that are becoming adamant). Lastly let me thank the Executive, District Council and all the members of Staff for your tireless efforts in serving the people of Bukomansimbi District and the Country at large. For God and my Country. Masereka Amis Asuman (Mr) Generated on 11/06/2020 05:25 1 LG Approved Workplan Vote:600 Bukomansimbi District FY 2020/21 SECTION A: Workplans for HLG Workplan 1a -

Health Systems Readiness to Provide Geriatric Friendly Care Services In

Ssensamba et al. BMC Geriatrics (2019) 19:256 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1272-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Health systems readiness to provide geriatric friendly care services in Uganda: a cross-sectional study Jude Thaddeus Ssensamba1,2* , Moses Mukuru1 , Mary Nakafeero3 , Ronald Ssenyonga3 and Suzanne N. Kiwanuka1 Abstract Background: As ageing emerges as the next public health threat in Africa, there is a paucity of information on how prepared its health systems are to provide geriatric friendly care services. In this study, we explored the readiness of Uganda’s public health system to offer geriatric friendly care services in Southern Central Uganda. Methods: Four districts with the highest proportion of old persons in Southern Central Uganda were purposively selected, and a cross-section of 18 randomly selected health facilities (HFs) were visited and assessed for availability of critical items deemed important for provision of geriatric friendly services; as derived from World Health Organization’s Age-friendly primary health care centres toolkit. Data was collected using an adapted health facility geriatric assessment tool, entered into Epi-data software and analysed using STATA version 14. Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’spost hoc tests were conducted to determine any associations between readiness, health facility level, and district. Results: The overall readiness index was 16.92 (SD ±4.19) (range 10.8–26.6). This differed across districts; Lwengo 17.91 (SD ±3.15), Rakai 17.63 (SD ±4.55), Bukomansimbi 16.51 (SD ±7.18), Kalungu 13.74 (SD ±2.56) and facility levels; Hospitals 26.62, Health centers four (HCIV) 20.05 and Health centers three (HCIII) 14.80. -

Bukomansimbi Profile.Indd

Bukomansimbi District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 Acknowledgement On behalf of Office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profiles. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer supported by Ogwang Jimmy, Disaster Preparedness Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfinch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred- Early Warning system Database programmer. My appreciation also goes to Bukomansimbi District Team. The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. Hon. Hilary O. Onek Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees BUKOMANSIMBI DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgement -

Coffee Value Chain Analysis Opportunities for Youth Employment in Uganda RURAL EMPLOYMENT RURAL EMPLOYMENT KNOWLEDGE MATERIALS – VALUE CHAINS

KNOWLEDGE MATERIALS – VALUE CHAINS Coffee value chain analysis Opportunities for youth employment in Uganda RURAL EMPLOYMENT RURAL EMPLOYMENT KNOWLEDGE MATERIALS – VALUE CHAINS Coffee value chain analysis Opportunities for youth employment in Uganda RURAL EMPLOYMENT by Francis Mwesigye and Hanh Nguyen Agrifood Economics Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2020 Required citation Mwesigye, F & Nguyen, H. 2020. Coffee value chain analysis: Opportunities for youth employment in Uganda. Rome, FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb0413en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-133098-2 © FAO, 2020 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution− NonCommercial−ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY−NC−SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons. -

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT No. 5 3Rd February

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT No. 5 3rd February, 2012 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT to The Uganda Gazette No. 7 Volume CV dated 3rd February, 2012 Printed by UPPC, Entebbe, by Order of the Government. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2012 No. 5. The Local Government (Declaration of Towns) Regulations, 2012. (Under sections 7(3) and 175(1) of the Local Governments Act, Cap. 243) In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Minister responsible for local governments by sections 7(3) and 175(1) of the Local Governments Act, in consultation with the districts and with the approval of Cabinet, these Regulations are made this 14th day of July, 2011. 1. Title These Regulations may be cited as the Local Governments (Declaration of Towns) Regulations, 2012. 2. Declaration of Towns The following areas are declared to be towns— (a) Amudat - consisting of Amudat trading centre in Amudat District; (b) Buikwe - consisting of Buikwe Parish in Buikwe District; (c) Buyende - consisting of Buyende Parish in Buyende District; (d) Kyegegwa - consisting of Kyegegwa Town Board in Kyegegwa District; (e) Lamwo - consisting of Lamwo Town Board in Lamwo District; - consisting of Otuke Town Board in (f) Otuke Otuke District; (g) Zombo - consisting of Zombo Town Board in Zombo District; 259 (h) Alebtong (i) Bulambuli (j) Buvuma (k) Kanoni (l) Butemba (m) Kiryandongo (n) Agago (o) Kibuuku (p) Luuka (q) Namayingo (r) Serere (s) Maracha (t) Bukomansimbi (u) Kalungu (v) Gombe (w) Lwengo (x) Kibingo (y) Nsiika (z) Ngora consisting of Alebtong Town board in Alebtong District; -

Mother and Baby Rescue Project (Mabrp) Sector: Health Sector

MOTHER AND BABY RESCUE PROJECT (MABRP) SECTOR: HEALTH SECTOR PROJECT LOCATION: LWENGO, MASAKA AND BUKOMANSIMBI DISTRICT CONTACT PERSONS: 1. Mrs. Naluyima Proscovia 2. Mr. Isabirye Aron 3. Ms. Kwagala Juliet [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +256755858994 Tel: +256704727677 Tel: +256750399870 PROJECT TITLE: Mother And Baby Rescue Project (MABRP) PROJECT AIM: Improving maternal and newborn health PROJECT DURATION: 12 Months PROJECT FINANCE PROJECT COST: $46011.39 USD Project overview This Project is concerned with improving their maternal and newborn health in rural areas of Lwengo District, Masaka District and Bukomansimbi District by providing the necessary materials to 750 vulnerable mothers through 15 Health Centres, 5 from each district. They will be given Maama kits, basins and Mosquito nets for the pregnant mothers. This will handle seven hundred fifty (750) vulnerable pregnant mothers within the three districts for two years providing 750 maama kits, 750 mosquito nets, and 750 basins within those two years Lwengo District is bordered by Sembabule District to the north, Bukomansimbi District to the north- east, Masaka District to the east, Rakai District to the south, and Lyantonde District to the west. Lwengo is 45 kilometres (28 mi), by road, west of Masaka, the nearest large city. The coordinates of the district are: 00 24S, 31 25E. Masaka District is bordered by Bukomansimbi District to the north-west, Kalungu District to the north, Kalangala District to the east and south, Rakai District to the south-west, and Lwengo District to the west. The town of Masaka, where the district headquarters are located, is approximately 140 kilometres (87 mi), by road, south-west of Kampala on the highway to Mbarara. -

The Political Economy of Violence in Uganda's Masaka

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 6 ~ Issue 11 (2018) pp.: 01-18 ISSN(Online) : 2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Insecurty In Maska District –Publication Astate Of Insecurity(delete): The Political Economy Of Violence In Uganda’s Masaka District Nabukeera Madinah (Phd) Senior Lecturer Islamic University in Uganda Females’ CampusFaculty of Management Studies Department of Public Administration ABSTRACT:This article examines the problem of insecurity in Uganda in areas of Masaka district in the western part of the country. It provides a typology of the insecurity incidents which occurred in areas of Bukomansimbi, Lwengo, Rakai, Sembabule, Kalungu, Nyendo, Lyantonde districts and Kingo sub-county and examines the steps which government and other stakeholders have taken to address the problem. Using a qualitative approach, interviews were conducted in the affected areas with LCI chairpersons, locals and area members of parliament together with library research to explain why these measures have failed to reduce the high level of crime that takes place in and around the country. The article focuses on three related issues: the political economy of the Uganda state;catalysts for insecurity and the manner in which the government and other actors have sought to manage the country's insecurity situation. Received 17 October, 2018; Accepted 03 Novenber, 2018 © The author(s) 2018. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org I. OVER VIEW Colonial Economy The mid-19th Century was a period of Scramble and Partition of Africa. Whether African societies resisted or collaborated, by 1914 the whole of African continent had been put under colonial administration with exception of Ethiopia and Liberia. -

Community HMIS in Uganda

Community HMIS in Uganda 21st SEPTEMBER 2017 Health Care System In Uganda Health Information System-Community Module ANALYSIS OF INDICATORS IN DHIS2 INDICATORS Jul to Sep Oct to Dec Jan Apr to Jun to March 2016 2016 2017 2017 Overall reporting rate 38.4% Total Number of sick Children 2 months – 5 years seen/attended to by 156,159 189,522 170,410 the VHT 219,14 0 Total Number of sick Children 2 months – 5 years with Diarrhoea 27,350 44,532 39,431 43,938 Total Number of sick Children 2 months – 5 years with Malaria 90,109 122,817 109,209 117,36 7 Total Number of sick Children 2 months – 5 years with fast breathing / 41,884 44,452 51,956 Pneumonia 45,724 Total Number of New Borns visited twice in the first week of life by the 16,231 14,618 14,205 VHT 15,781 Total Number of Children under 5 years referred to the Health Unit 14,805 16,156 21,300 20,891 Total Number of Children under 5 years with red MUAC 3,686 2,321 2,719 2,697 Total Number of Villages with stock out of ORS 2,033 1,891 3,086 3,440 Total number of Villages with stock out of the first line anti-Malarial 2,769 4,154 4,239 4,603 Total Number of Villages with Stock out of Amoxicillin 2,732 3,189 3,204 4,423 REPORTING PER PARTNER IMPLEMENTING DISTRICTS REPORTING PERCENTAGE PERCENTAGE PARTNER REPORTING REPORTING ( APRIL-JUN ( JAN-MARCH 2017) 2017) Global Fund Agago,Amuru,Bushenyi,Gulu,Lira,Omoro,Kasese,Luweero 30.7%( 26) 38.5%(10) Malaria Consortium Buliisa,Kabarole,Kamwenge,Kagadi,Kamwenge,Kiryandongo,Kyan 73.3%(15) 73.3%(15) kwazi,Kyemjojo,Kyegwegwa,Kiboga,Mityana UNICEF Abim,Amudat,Bukomansimbi,Butambala,Kaabong,Kalungu,Gomba -

Bukomansimbi District Map Map of Uganda

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA BUKOMANSIMBI DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT STATISTICAL ABSTRACT 2018/2019 BUKOMANSIMBI DISTRICT MAP MAP OF UGANDA Bukomansimbi District Local Government P.O Box 293, Masaka JUNE 2019 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.bukomansimbi.go.ug Bukomansimbi District Statistical Abstract for 2018/2019 FOREWORD The importance of statistics in informing planning and monitoring of government programmes cannot be over emphasized. We need to know where we are, determine where we want to reach and also know whether we have reached there. The monitoring of socio-economic progress is not possible without measuring how we progress and establishing whether human, financial and other resources are being used efficiently. However, these statistics have in many occasions been national in outlook and less district specific. The development of a district-based Statistical Abstract shall go a long way to solve this gap and provide district tailored statistics and will reflect the peculiar nature of the district by looking at specific statistics which would not be possible to provide at a higher level. This District Statistical Abstract will go a long way in guiding District Policy makers, Planners, Researchers and other stakeholders to identify the indicators that are relevant for planning, monitoring and evaluation of Government programmes in their jurisdiction. It will also act as an aggregation of statistics from all sectors and also information originating from NGOs and other organisations. This Statistical Abstract, therefore, is an annual snapshot documentation of the Bukomansimbi District situation, providing a continuous update of the district status. Lastly, I thank the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) for the continued technical support to Bukomansimbi District.