Barack Obama's Dreams from My Father

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obama and the Black Political Establishment

“YOU MAY NOT GET THERE WITH ME …” 1 OBAMA & THE BLACK POLITICAL ESTABLISHMENT KAREEM U. CRAYTON Page | 1 One of the earliest controversies involving the now historic presidential campaign of Barack Obama was largely an unavoidable one. The issue beyond his control, to paraphrase his later comment on the subject, was largely woven into his DNA.2 Amidst the excitement about electing an African-American candidate to the presidency, columnist Debra Dickerson argued that this fervor might be somewhat misplaced. Despite his many appealing qualities, Dickerson asserted, Obama was not “black” in the conventional sense that many of his supporters understood him to be. While Obama frequently “invokes slavery and Jim Crow, he does so as one who stands outside, one who emotes but still merely informs.”3 Controversial as it was, Dickerson’s observation was not without at least some factual basis. Biologically speaking, for example, Obama was not part of an African- American family – at least in the traditional sense. The central theme of his speech at the 2004 Democratic convention was that only a place like America would have allowed his Kenyan father to meet and marry his white American mother during the 1960s.4 While 1 Special thanks to Vincent Brown, who very aptly suggested the title for this article in the midst of a discussion about the role of race and politics in this election. Also I am grateful to Meta Jones for her helpful comments and suggestions. 2 See Senator Barack Obama, Remarks in Response to Recent Statements b y Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright Jr. -

The Other Father in Barack Obama's Dreams from My Father

The Other Father in Barack Obama’s Dreams from my Father Robert Kyriakos Smith and King-Kok Cheung Much has been written about the father mentioned in the title of Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father (1995), the Kenyan namesake who sired and soon abandoned the forty-fourth president of the United States. Also well noted is Stanley Ann Dunham, Obama’s White American mother who has her own biography, entitled A Singular Woman (2011). The collated material concerning this f eeting family of three lends itself to a simple math: Black father + White mother = Barack Obama; or, Africa + America = Barack Obama. But into these equations the present essay will introduce third terms: “ Asian stepfather” and “ Indonesia.” For if Barack Obama’s biography is to be in any way summed up, we must take into account both Lolo Soetoro (Obama’s Indonesian stepfather) and the nation of Lolo’s birth, a country where Obama spent a signif cant portion of his youth. Commentators’ neglect of Lolo, especially, is a missed literary-critical opportunity we take advantage of in the following essay. The fact that the title of Obama’s memoir explicitly references only one father may be seen to compound the oversight, especially since “my father” is a position that the absentee Barack Sr. for the most part, vacates. However, “my father” is also fundamentally a function that several people in Barack Jr.’s life perform. Therefore, in a sense, the Father of Obama’s title is always already multiple, pointing simultaneously to a biological father and to his surrogates. -

Barack Obama's Race Speech at the Constitution Center

Barack Obama’s Race Speech at the Constitution Center Transcript | National Constitution Center, March 18, 2008 "We the people, in order to form a more perfect union." Two hundred and twenty one years ago, in a hall that still stands across the street, a group of men gathered and, with these simple words, launched America's improbable experiment in democracy. Farmers and scholars; statesmen and patriots who had traveled across an ocean to escape tyranny and persecution finally made real their declaration of independence at a Philadelphia convention that lasted through the spring of 1787. The document they produced was eventually signed but ultimately unfinished. It was stained by this nation's original sin of slavery, a question that divided the colonies and brought the convention to a stalemate until the founders chose to allow the slave trade to continue for at least twenty more years, and to leave any final resolution to future generations. Of course, the answer to the slavery question was already embedded within our Constitution - a Constitution that had at is very core the ideal of equal citizenship under the law; a Constitution that promised its people liberty, and justice, and a union that could be and should be perfected over time. And yet words on a parchment would not be enough to deliver slaves from bondage, or provide men and women of every color and creed their full rights and obligations as citizens of the United States. What would be needed were Americans in successive generations who were willing to do their part - through protests and struggle, on the streets and in the courts, through a civil war and civil disobedience and always at great risk - to narrow that gap between the promise of our ideals and the reality of their time. -

Barack Obama Dreams from My Father

Barack Obama Dreams from My Father “For we are strangers before them, and sojourners, as were all our fathers. 1 CHRONICLES 29:15 PREFACE TO THE 2004 EDITION A LMOST A DECADE HAS passed since this book was first published. As I mention in the original introduction, the opportunity to write the book came while I was in law school, the result of my election as the first African-American president of the Harvard Law Review. In the wake of some modest publicity, I received an advance from a publisher and went to work with the belief that the story of my family, and my efforts to understand that story, might speak in some way to the fissures of race that have characterized the American experience, as well as the fluid state of identity- the leaps through time, the collision of cultures-that mark our modern life. Like most first-time authors, I was filled with hope and despair upon the book’s publication-hope that the book might succeed beyond my youthful dreams, despair that I had failed to say anything worth saying. The reality fell somewhere in between. The reviews were mildly favorable. People actually showed up at the readings my publisher arranged. The sales were underwhelming. And, after a few months, I went on with the business of my life, certain that my career as an author would be short-lived, but glad to have survived the process with my dignity more or less intact. I had little time for reflection over the next ten years. I ran a voter registration project in the 1992 election cycle, began a civil rights practice, and started teaching constitutional law at the University of Chicago. -

The Riddle of Barack Obama: a Psychoanalytic Study

Vol. 8(9), pp. 333-355, December 2014 DOI: 10.5897/AJPSIR08.060 African Journal of Political Science and Article Number: 8C0A79448623 International Relations ISSN 1996-0832 Copyright © 2014 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJPSIR Full Length Research Paper The riddle of Barack Obama: A psychoanalytic study Avner Falk Jerusalem, Israel. Received 9 December, 2008; Accepted 1 September, 2009 In August 2008 the 47-year-old Barack Hussein Obama was elected by the U.S. Democratic National Convention as its nominee for President of the United States. This was the first time an African- American had ever been nominated to this office. It was a momentous and revolutionary event. The bright African-American orphan son of a bright but tragic Kenyan father, who had died in a tragic car accident in 1982 in Kenya, after losing his career and his legs and struggling with alcoholism, and of a bright white mother who had died of cancer in 1995, was nominated for the highest office in the world’s mightiest country. Soon Obama was leading in most public-opinion polls as the candidate most likely to become President, with a 10-point lead over John McCain, the Republican candidate. On November 4 he was elected President of the United States, the first African-American president in U.S. history. There had been nothing quite like this in U.S. history. On January 20, 2009 Barack Obama became the 44th president of the United States. Key words: Barrack Obama, CSV qualities, psychoanalytic knowledge, culture. INTRODUCTION There are numerous schools in psychology, psychiatry by the vast majority of cultures and throughout history, and psychoanalysis. -

Contents Immediate Family

The family of Barack Obama, the 44th President of the United States of America, is made up of people of African American, English, Kenyan (Luo), and Irish heritage,[1][2] who are known through Obama's writings and other reports.[3][4][5][6] His immediate family is the First Family of the United States. The Obamas are the first First Family of African descent. Contents 1 Immediate family 2 Maternal relations 3 Paternal relations 4 Michelle Robinson Obama's extended family 5 Genealogical charts o 5.1 Ancestries o 5.2 Family trees 6 Distant relations 7 Index 8 See also 9 References 10 External links Immediate family Michelle Obama Michelle Obama, née Robinson, the wife of Barack Obama, was born on January 17, 1964, in Chicago, Illinois. She is a lawyer and was a University of Chicago Hospital vice-president. She is the First Lady of the United States. Malia Obama and Sasha Obama Barack and Michelle Obama have two daughters: Malia Ann /məˈliːə/, born on July 4, 1998,[7] and Natasha (known as Sasha /ˈsɑːʃə/), born on June 10, 2001.[8] They were both delivered by their parents' friend Dr. Anita Blanchard at University of Chicago Medical Center.[9] Sasha is the youngest child to reside in the White House since John F. Kennedy, Jr. arrived as an infant in 1961.[10] Before his inauguration, President Obama published an open letter to his daughters in Parade magazine, describing what he wants for them and every child in America: "to grow up in a world with no limits on your dreams and no achievements beyond your reach, and to grow into compassionate, committed women who will help build that world."[11] While living in Chicago, the Obamas kept busy schedules, as the Associated Press reports: "soccer, dance and drama for Malia, gymnastics and tap for Sasha, piano and tennis for both."[12][13] In July 2008, the family gave an interview to the television series Access Hollywood. -

The Fictive Force of Barack Obama's Dreams from My Father

The Fictive Force of Barack Obama's Dreams from My Father Alan Shima University of Gavle Abstract: Barack Obama '.I' memoir Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and In heritance ( 1995) has been an enormous public success since it was re-issued in 2004. Obama 's narrative is a powerfully crafted account of a personal quest that rhetori cally transverse.1· over geographical boundaries and literary genres. What imerests me about this work is how it poetically plaits personal history with cultural my1h, unbolting fact with imagi11atio11. Textually contiguous 1vith other A,/i-ican American stories of self representation a11d liberation, Dreams from My Father strikes me as a potent narrative of self-i11scriptio11. To put it in its simplest pe1formative expression, the narrator ofthis book asks "who am J" and in doing so writes itself into place, not as an identity found but as the subject in writing. Keywords: Barack Obama- persona/ narrative-self-inscription-memoir- autohi ography- sto1y telling- hild1111gsro111an - Shelby Steele .. the modern scriptor is born simultaneously with the text, is in no way equipped with a being preceding or exceeding the writing, is not the subject with the book as predicate; there is no other lime than that of the enunciation and every text is eternally written here and no1v. Roland Barthes, "The Death of the Author" 4 American Studies in Scandinavia, 4 J: J, 2009 Introduction To recall the past is precarious at the best of times. For a writer of personal narratives, such challenges presume a measure of spirit, a faith in making meaningful what is not quite present, a hope that imagination will prevai l when memory fails. -

The Literary Candidate

CHAPTER THIRTEEN The Literary Candidate osh Kalven loved walking through Hyde Park—across the University J of Chicago’s campus, past his university-affiliated high school, and along the Lake Michigan shore. Those strolls guaranteed him some teen- age freedom; they also got him to his part-time job at 57th Street Books, an independent bookstore that belonged to the neighborhood’s Seminary Co-op. One day in the spring of 1996, Kalven walked past a yard sign on Lake Park Avenue. It was odd that he noticed it; most teenagers tune out bids for the state senate. It was even odder that he recognized the name. Where had he seen that name, Obama? Oh yeah, Kalven remembered, that guy’s a member at the bookstore. Barack Obama first joined the Co-op in 1986, and for many years he would duck into 57th Street’s basement location, wearing a leather jacket in the winter and shirtsleeves rolled up in the summer, browsing quietly while the shop echoed with the sounds of the apartment dwellers above. Obama often came at night, just before closing, circling the new releases table in the front, studying the staff selections along the back, and usu- ally leaving with a small stack of novels and nonfiction. At the counter, he would spell his name to get the member discount—a treasured and anonymous ritual unless your name was strange enough, and your visits frequent enough, that a clerk might remember you. Obama’s anonymity ended for good in 2004, when he gave his iconic keynote at the Democratic National Convention. -

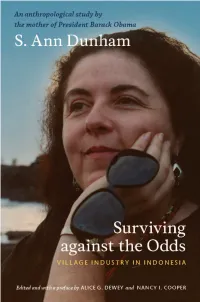

For Review Copies Or Interviews, Contact

For Immediate Release December 2009 PRESIDENT OBAMA’S MOTHER’S DISSERTATION PUBLISHED 14 YEARS AFTER HER DEATH Duke University Press Proud to Publish S. Ann Dunham’s Surviving against the Odds: Village Industry in Indonesia Duke University Press is proud to announce the publication of an anthropological study by S. Ann Dunham, the mother of President Barack Obama. Dunham, who died in 1995, completed the dissertation in anthropology for the University of Hawaii in 1992. Surviving against the Odds: Village Industry in Indonesia is based on Dunham’s research, over a period of 14 years, among the rural craftsmen of Java. The book centers on the metalworking industries in the Javanese village of Kajar, and how they offer a viable economic alternative in a rice-dependent area of rural Southeast Asia. Through the book we now have a more complete picture of President Obama’s mother. Her ideas on development and microfinance seem ahead of their time. Dunham’s role as a benefactor and her generous spirit were remarked upon by villagers in Kajar when a London Times reporter visited there recently. According to her daughter, Maya Soetoro-Ng, Dunham passed along a deep respect for other cultures to her children. The book was launched at the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association on December 3, 2009. Dunham and her work were the subject of a Presidential Session and a special reception. Editors Alice G. Dewey and Nancy I. Cooper attended as well as Maya Soetoro-Ng and Duke Press’s Editorial Director, Ken Wissoker. Wissoker sees Surviving against the Odds as a good fit with Duke University Press’s list in anthropology and believes that the book will strike a chord with anthropologists in particular. -

The Deplorable Behavior of President Obama Towards Native Homeland in Africa Mary

East African Scholars Journal of Education, Humanities and Literature Abbreviated Key Title: East African Scholars J Edu Humanit Lit ISSN 2617-443X (Print) | ISSN 2617-7250 (Online) | Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya DOI: 10.36349/easjehl.2019.v02i01.007 Volume-2 | Issue-1 | January-2019 | Short Communication The Deplorable Behavior of President Obama towards Native Homeland in Africa Mary. M1, Dickens. Johnson2 Honolulu, Hawaii *Corresponding Author Mary. M Abstract: President Obama has claimed a close spiritual relationship with Africa in his book entitled Dreams of My Father. However, his behavior indicates a lack of a compassionate nurturing bond with the homeland, in fact, mostly actions of neglect and denial of support for blood relatives. Keywords: Obama publications, relative of Obama in Africa, Kenyan school, gift of goats, denial of passport visa. INTRODUCTION compassion for the poor peoples of native homeland In spite of writing heartfelt books about love of Africa. the African homeland of his father (Dreams of my Father, Obama, 1995), the behavior of President Obama Contrast to the American Presidency “Obamacare towards the countrymen of the native homeland show a Hero” different behavior. For instance, a school was named What a sharp contrast to the views of after him in the hopes of financial support and monetary Americans who saw President Obama as holding up backing, but it never came through (D’Souza, 2012). democratic values and carrying through Hillary Clinton’s pioneering work on healthcare to fruition with Moreover, interviews requested with relative the creation of Obamacare labeled health programs for requiring the gift of goats were not readily provided and U.S. -

History from Below in Obama's Dreams from My Father This

History from Below in Obama’s Dreams from My Father This research paper explores the autobiographical memoirof Barack Obama from theoretical perspective of ‘new historicism ’. The paper begins with short introduction of the book Dreams from My Father connecting it with the research topic ‘History from Below’and digs out the context in which the book was written. Then the study attempts to analyse how Obama has finely experienced the same level of prejudice as his father and forefathersand it also attempts how his experiences of racial prejudice can also be counted under collective experience of people from margin. The paper explains how Obama’s autobiography gets meaning as part of the larger black community’s story in white dominated society that dominates black people’s history and its racial past.The writer’s motive behind recollecting his racial past in the memoir is actually an attempt to investigate his inheritance and the history of deeply grounded racial prejudice in America. Key words: History from below, racial identity, the blacks; inheritance,prejudice The present research paper analyses an autobiographical memoir of Obama titled Dreamsfrom My Father(1995).It is a story of race and inheritance. Obama celebrates his autobiography through narratives. The novel highlights and excavates ordinary African ordinary people’s history which has been elided.It tends to realize historians “history without people”. History from Belowquestions why the so-called civilized, socializedand most educated people of America prove as care- taker of human right as secured in constitution whereas practical eyes lacks to address the real issues of racism. -

Dreams from My Father: a Story of Race and Inheritance

Summer Reading Assignments 20162017 Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance by Barack Obama In this lyrical, unsentimental, and compelling memoir, the son of a black African father and a white American mother searches for a workable meaning to his life as a black American. It begins in New York, where Barack Obama learns that his father—a figure he knows more as a myth than as a man—has been killed in a car accident. This sudden death inspires an emotional odyssey—first to a small town in Kansas, from which he retraces the migration of his mother’s family to Hawaii, and then to Kenya, where he meets the African side of his family, confronts the bitter truth of his father’s life, and at last reconciles his divided inheritance. Pictured in lefthand photograph on cover: Habiba Akumu Hussein and Barack Obama, Sr. (President Obama's paternal grandmother and his father as a young boy). Pictured in righthand photograph on cover: Stanley Dunham and Ann Dunham (President Obama's maternal grandfather and his mother as a young girl). Dear USA Students, The upcoming 20162017 school year will prove to be an exciting one at Urban Science Academy. Your teachers and staff are planning engaging curriculum that will open up endless possibilities for you as lifelong learners. The beginning of this journey, for all of us, is the communitywide reading of the memoir Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance by President Barack Obama. You also have an alternative novel to select from entitled Enrique’s Journey by Sonia Nazario.