Private Sector Development Strategy for the Lake Victoria Basin Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Fire Baseline for Tanzania

Sustainable Forest Management in a Changing Climate FAO‐Finland Forestry Programme – TANZANIA A Fire Baseline for Tanzania Dar es Salaam 2013 Executive Summary In Tanzania wild fires are reported to be increasing at an alarming rate. The problem of wildfires in Tanzania is complex and should not be addressed on a sectoral level as it concerns all the aspects related to forest and land management, prevention, suppression, and post‐fire management. It is a problem of general policy, land policy and forest policy and legislation, as much as it is a problem of equipment and capacity building within any one sector. Despite the magnitude of threat suggested, hard data on the number and extent of wildfires are lacking, most statements on the wildfire issue are based on story and opinions (Madoffe et al., 2005). Wildfires are considered to be a ‘problem’. However, the data and information to describe the extent, nature, impacts and source of wildfires have not been compiled and analyzed; this is a Fire Baseline, which is the subject of the work reported here. The main objective of this study was to elaborate “Tanzanian wildfire baseline information”, as the starting point for a Fire Information System. The step taken in compiling this fire baseline for Tanzania is a sound strategic one and should be something that is repeated in most countries that are working to understand and account for fires in their landscapes. In the preparation of the Fire Baseline there have been a series of aspects that have been indentified, which can provide a set of ongoing analyses to further refine and contribute to enhancing the insights and understanding of fire in Tanzania. -

Les Parcs Nationaux

Tanzanie LES PARCS NATIONAUX FRENCH 64135_FR Brochure Tanzania.indd 1 07-05-14 08:55 Tanzanie Bienvenue dans cette diversité d’une incomparable beauté que nous sommes fiers d’appeler notre patrie. Une terre que nous aimerions partager avec vous aujourd’hui et que nous préservons de manière active pour les générations futures. Ainsi, une partie du pays a été préservée à des fins de conservation. Le fameux Parc national de Sérengéti et l’immense Réserve de gibier de Selous représentent l’apogée d’une riche mosaïque d’environnements protégés qui, ensemble, abritent environ 20% de la population des gros mammifères d’Afrique. Serengeti Rubondo National National Park Park Saanane Arusha Mt Kilimanjaro National Park National Park National Park Lake Manyara Mkomazi National Park 2 Tarangire National Park Gombe National National Park Park Mahale National Park Saadani National Park Ruaha National Katavi Park Mikumi National Park National Park Udzungwa National Park Kitulo National Park Afrique Parc national d’Arusha 4 Parc national du Lac Manyara 16 Parc national de l’île de Saanane 28 Parc national de Gombe Stream 6 Parc national de Mikumi 18 Parc national de Sérengéti 30 Parc national de Katavi 8 Parc national de Mkomazi 20 Parc national de Tarangire 32 Parc national du Kilimanjaro 10 Parc national de Ruaha 22 Parc national des monts Udzungwa 34 Parc national de Kitulo 12 Parc national de l’île de Rubondo 24 Le rôle des parcs 36 Parc national de Mahale 14 Parc national de Saadani 26 Astuces de voyage 38 64135_FR Brochure Tanzania.indd 2 07-05-14 08:55 Karibu Tanzania – Bienvenue! La Tanzanie est un pays possédant diverses facettes et de nombreux La diversité naturelle extraordinaire de la Tanzanie se reflète par une records mondiaux. -

George Jambiya Simon Milledge Nangena Mtango TRAFFIC East/Southern Africa

‘NIGHT TIME SPINACH’ CONSERVATION AND LIVELIHOOD IMPLICATIONS OF WILD MEAT USE IN REFUGEE SITUATIONS IN NORTH-WESTERN TANZANIA George Jambiya Simon Milledge Nangena Mtango TRAFFIC East/Southern Africa Published by TRAFFIC East/Southern Africa. © 2007 TRAFFIC East/Southern Africa. All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC East/Southern Africa as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, IUCN – The World Conservation Union, or the Rufford Maurice Laing Foundation. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. TRAFFIC is UK Registered Charity No. 1076722. Suggested citation: Jambiya, G., Milledge, S.A.H. and Mtango, N. (2007). ‘Night Time Spinach’: Conservation and livelihood implications of wild meat use in refugee situations in north-western Tanzania. TRAFFIC East/Southern Africa, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Key words: Wild meat, refugees, Tanzania. ISBN: 978-1-85850-231-1 -

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 6 IUCN - The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biologi- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna cal diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- of fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their vation of species or biological diversity. conservation, and for the management of other species of conservation con- cern. Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: sub-species and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintaining biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of bio- vulnerable species. logical diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conservation Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitoring 1. To participate in the further development, promotion and implementation the status of species and populations of conservation concern. of the World Conservation Strategy; to advise on the development of IUCN's Conservation Programme; to support the implementation of the • development and review of conservation action plans and priorities Programme' and to assist in the development, screening, and monitoring for species and their populations. -

Small Carnivore Conservation Action Plan

Durant, S. M., Foley, C., Foley, L., Kazaeli, C., Keyyu, J., Konzo, E., Lobora, A., Magoma, N., Mduma, S., Meing'ataki, G. E. O., Midala, B. D. V. M., Minushi, L., Mpunga, N., Mpuya, P. M., Rwiza, M., and Tibyenda, R. The Tanzania Small Carnivore Conservation Action Plan. Durant, S. M., De Luca, D., Davenport, T. R. B., Mduma, S., Konzo, S., and Lobora, A. Report: 162-269. 2009. Arusha, Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute. Keywords: 1TZ/abundance/action plan/caracal/Caracal caracal/conservation/conservation action plan/distribution/ecology/Felis silvestris/Leptailurus serval/serval/wildcat Abstract: This report covers the proceedings of the First Tanzania Small Carnivore Conservation Action Plan Workshop held at TAWIRI on 19th-21st April 2006. The workshop brought together key stakeholders to assess existing information and establish a consensus on priorities for research and conservation for 28 species of small to medium carnivore in Tanzania (excluding cheetah, wild dogs, aardwolf, spotted hyaena, striped hyaena, leopard and lion, all of which were covered in other workshops). Recent records were used to confirm the presence of 27 of these species in Tanzania. These were three species of cats or felids: serval (Leptailurus serval); caracal (Caracal caracal) and wild cat (Felis silvestris). Five mustelids: Cape clawless otter (Aonyx capensis); spotted-necked otter (Hydrictis maculicollis); honey badger (Mellivora capensis); striped weasel (Poecilogale albinucha); and zorilla (Ictonyx striatus). Four canids: bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis); black-backed jackal (Canis mesomelas); golden jackal (Canis aureus); side-striped jackal (Canis adustus). Four viverrids: common genet (Genetta genetta); large-spotted genet (Genetta maculata); servaline genet (Genetta servalina); and African civet (Viverra civettina). -

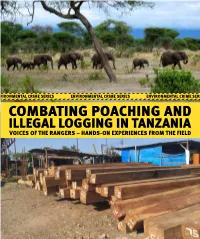

Combating Poaching and Illegal Logging in Tanzania Voices of the Rangers – Hands-On Experiences from the Field

ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME SERIES ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME SERIES ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME SERIES COMBATING POACHING AND ILLEGAL LOGGING IN TANZANIA VOICES OF THE RANGERS – HANDS-ON EXPERIENCES FROM THE FIELD 1 Editorial Team Frode Smeby, Consultant, GRID-Arendal Rune Henriksen, Consultant, GRID-Arendal Christian Nellemann, GRID-Arendal (Current address: Rhipto Rapid Response Unit, Norwegian Center for Global Analyses) Contributors Benjamin Kijika, Commander, Lake Zone Anti-Poaching Unit Rosemary Kweka, Pasiansi Wildlife Institute Lupyana Mahenge, Lake Zone Anti-Poaching Unit Valentin Yemelin, GRID-Arendal Luana Karvel, GRID-Arendal Anonymous law enforcement officers from across Tanzania. The rangers have been anonymized in order to protect them from the risk of retributions. The authors gratefully acknowledge the sharing of information and experiences by these rangers, who risk their lives every day in the name of conservation. Cartography Riccardo Pravettoni All photos © Frode Smeby and Rune Henriksen Norad is gratefully acknowledged for providing the necessary ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME SERIES funding for the project and the production of this publication. 2 COMBATING POACHING AND ILLEGAL LOGGING IN TANZANIA VOICES OF THE RANGERS – HANDS-ON EXPERIENCES FROM THE FIELD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 WILDLIFE CRIME 6 ILLEGAL LOGGING 9 CHARCOAL 10 GENERAL INTRODUCTION 12 WILDLIFE CRIME 15 EXPERIENCES 16 CHALLENGES 17 SITUATION OF THE LAKE ZONE ANTI-POACHING UNIT 21 FIELD EVALUATION OF LAKE ZONE ANTI-POACHING UNIT 23 UGALLA GAME RESERVE 29 ILLEGAL LOGGING 35 CORRUPTION AND -

Profile on Environmental and Social Considerations in Tanzania

Profile on Environmental and Social Considerations in Tanzania September 2011 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) CRE CR(5) 11-011 Table of Content Chapter 1 General Condition of United Republic of Tanzania ........................ 1-1 1.1 General Condition ............................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Location and Topography ............................................................. 1-1 1.1.2 Weather ........................................................................................ 1-3 1.1.3 Water Resource ............................................................................ 1-3 1.1.4 Political/Legal System and Governmental Organization ............... 1-4 1.2 Policy and Regulation for Environmental and Social Considerations .. 1-4 1.3 Governmental Organization ................................................................ 1-6 1.4 Outline of Ratification/Adaptation of International Convention ............ 1-7 1.5 NGOs acting in the Environmental and Social Considerations field .... 1-9 1.6 Trend of Aid Agency .......................................................................... 1-14 1.7 Local Knowledgeable Persons (Consultants).................................... 1-15 Chapter 2 Natural Environment .................................................................. 2-1 2.1 General Condition ............................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Wildlife Species .................................................................................. -

Natural, Cultural and Tourism Investment Opportunities 2017

UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA MINISTRY OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND TOURISM NATURAL, CULTURAL AND TOURISM INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES 2017 i ABBREVIATIONS ATIA - African Trade Insurance Agency BOT - Build, Operate and Transfers CEO - Chief Executive Officer DALP - Development Action License Procedures DBOFOT - Design, Build, Finance, Operate and Transfer FDI - Foreign Direct Investment GDP - Gross Domestic Product GMP - General Management Plan ICSID - International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes MIGA - Multilateral Investment Guarantee MNRT - Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism Agency MP - Member of Parliament NCA - Ngorongoro Conservation Area NCAA - Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority PPP - Public Private Partnerships TANAPA - Tanzania National Parks TAWA Tanzania Wildlife Management Authority TFS - Tanzania Forest Services TIC - Tanzania Investment Centre TNBC - Tanzania National Business Council VAT - Value Added Tax ii TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND TOURISM ............................................................................................................ xi CHAPTER ONE ................................................................................................... 1 TANZANIA IN BRIEF ........................................................................................ 1 1.1 An overview .......................................................................................................................................1 1.2Geographical location and size ........................................................................................................1 -

Black Rhino Disaster in Tanzania Markus Borner

Black Rhino Disaster in Tanzania Markus Borner The black rhino will be exterminated soon in northern Tanzania if poaching is not stopped, says the author, after surveying eight national parks and game reserves, either from the air or on the ground, or both. Tanzania is making great efforts to stop the poaching, but essential equipment is desperately short, and much more outside help is needed. The black Rhinoceros Diceros bicornis is still the most numerous of the five rhino species. But in the last few years it has been the one most heavily poached, and most East African populations have been drastically reduced. Kenya in the last ten years has lost over 90 per cent of its black rhinos, and today fewer than 1500 survive in scattered populations.13 In a recent report to the IUCN/SSC African Rhino Group Dr Esmond Bradley Martin attributed the present onslaught to an increased demand for rhino horn on the world market,4 not only for the traditional medical purposes in the Far East, but also for the new market in North Yemen, where the horns are carved into dagger handles, and where 22,645 kilos of rhino horn were imported between 1969 and 1977.4 The world market has consumed at least 7.75 tonnes of rhino horn annually in recent years, for which about 2580 rhinos were killed every year. Because of the growing demand the price in the last four years has increased some 2000 per cent, reaching a minimum wholesale price of US$675 a kilo in South-east Asia in 1979. -

Wildlife Corridors in Tanzania

Wildlife Corridors in Tanzania Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute PO Box 661 Arusha Tanzania January 2009 Edited by: Trevor Jones, Tim Caro & Tim R.B. Davenport Contributions by: Animal Behaviour Research Unit (Mikumi NP), T. Caro, T. Danielsen, T.R.B. Davenport, K. Doody, C. Epps, C. Foley, L. Foley, R. Hahn, J.J. Halperin, S. Hassan, T. Jones, B. Mbano, D.G. Mpanduji, F. Mofulu, T. Morrison, D. Moyer, F. Msoffe, A. Mtui, B. Mutayoba, R. Nielsen, W. Ntongani, L. Pintea, F. Rovero, Selous-Niassa Wildlife Corridor Group Cartography by: T.R.B. Davenport, N. McWilliam, T. Jones, H. Olff, L. Pintea, C. Epps, D.G. Mpanduji, J.J. Halperin, A. Cauldwell, Guy Picton Phillipps, Biharamulo District Natural Resources Office and Cartography Unit, Geography Department, University of Dar es Salaam Recommended citation Jones, T., Caro, T. & Davenport, T.R.B. (Eds.). 2009. Wildlife Corridors in Tanzania. Unpublished report. Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI), Arusha. 60 pp. Acknowledgments The Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI) and the editors wish to very gratefully acknowledge all the individuals and organisations that provided information on the various corridors. The production of the report was funded by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) www.wcs.org/tanzania. Cover photo: Bujingijila Corridor, Southern Highlands © Tim Davenport / WCS For further information email: [email protected] 2 Statement The contributors to this document support the conservation of wildlife corridors across Tanzania. It is their contention that wildlife corridors can help secure national interests (water, energy, tourism, biodiversity, carbon sinks and development) and can also meet the needs and rights of local communities. -

Black Rhino Disaster in Tanzania Markus Borner

The original paper was published in the Journal of the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire (1903-1925 and 1926-1950) or in Oryx, the journal of Fauna and Flora International (from 1951). The website of the journal is (from 2008): http://www.oryxthejournal.org/ The PDF is reproduced with permission from the CD version of The Centenary Archive 1903-2003, a fully searchable database of 100 years of the publications of Fauna and Flora International. More information on: http://www.fauna-flora.org/ The Society was founded in 1903 as the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire, and subsequently named the Fauna and Flora Preservation Society. Fauna & Flora International is conserving the planet’s threatened species and ecosystems – with the people and communities who depend on them. Oryx - The International Journal of Conservation, is now published quarterly by Cambridge University Press on behalf of Fauna & Flora International. It is a leading scientific journal of biodiversity conservation, conservation policy and sustainable use, with a particular interest in material that has the potential to improve conservation management and practice. The website, http://www.oryxthejournal.org/, plays a vital role in the journal’s capacity-building work. Amongst the site’s many attributes is a compendium of sources of free software for researchers and details of how to access Oryx at reduced rates or for free in developing countries. The website also includes extracts from Oryx issues 10, 25 and 50 years ago, and a gallery of research photographs that provide a fascinating insight into the places, species and people described in the journal. -

Emerging Issues and Challenges in Conservation of Biodiversity in the Rangelands of Tanzania

A peer-reviewed open-access journal Nature EmergingConservation issues 6: 1–29 and (2013) challenges in conservation of biodiversity in the rangelands of Tanzania 1 doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.6.5407 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://www.pensoft.net/natureconservation Launched to accelerate biodiversity conservation Emerging issues and challenges in conservation of biodiversity in the rangelands of Tanzania Jafari R. Kideghesho1, Alfan A. Rija1, Kuruthumu A. Mwamende2, Ismail S. Selemani2 1 Department of Wildlife Management, Sokoine University of Agriculture (SUA), P.O. Box 3073, Chuo Kikuu, Morogoro Tanzania 2 Range Management Section, Department of Animal Science & Production, P. O. Box, 3004, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Chuo Kikuu, Morogoro Tanzania Corresponding author: Alfan A. Rija ([email protected]) Academic editor: Klaus Henle | Received 25 April 2013 | Accepted 20 August 2013 | Published 18 November 2013 Citation: Kideghesho JR, Rija AA, Mwamende KA, Selemani IS (2013) Emerging issues and challenges in conservation of biodiversity in the rangelands of Tanzania. Nature Conservation 6: 1–29. doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.6.5407 Abstract Tanzania rangelands are a stronghold for biodiversity harbouring a variety of animal and plant species of economic, ecological and socio-cultural importance. Efforts to protect these resources against destruction and loss have involved, among other things, setting aside some tracks of land as protected areas in the form of national parks, nature reserves, game reserves, game controlled and wildlife management areas. However, these areas and adjacent lands have long been subjected to a number of emerging issues and challenges, which complicate their management, thus putting the resources at risk of over exploitation and extinction.