Inhabiting American Literary Modernism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questionnaire Responses Emily Bernard

Questionnaire Responses Emily Bernard Modernism/modernity, Volume 20, Number 3, September 2013, pp. 435-436 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2013.0083 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/525154 [ Access provided at 1 Oct 2021 22:28 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] questionnaire responses ments of the productions of the Harlem Renaissance? How is what might be deemed 435 a “multilingual mode of study” vital for our present day work on the movement? The prospect of a center for the study of the Harlem Renaissance is terribly intriguing for future scholarly endeavors. Houston A. Baker is Distinguished University Professor and a professor of English at Vander- bilt University. He has served as president of the Modern Language Association of America and is the author of articles, books, and essays devoted to African American literary criticism and theory. His book Betrayal: How Black Intellectuals Have Abandoned the Ideals of the Civil Rights Era (2008) received an American Book Award for 2009. Emily Bernard How have your ideas about the Harlem Renaissance evolved since you first began writing about it? My ideas about the Harlem Renaissance haven’t changed much in the last twenty years, but they have expanded. I began reading and writing about the Harlem Renais- sance while I was still in college. I was initially drawn to it because of its surfaces—styl- ish people in attractive clothing, the elegant interiors and exteriors of its nightclubs and magazines. Style drew me in, but as I began to read and write more, it wasn’t the style itself but the intriguing degree of importance assigned to the issue of style that kept me interested in the Harlem Renaissance. -

A History of African American Theatre Errol G

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-62472-5 - A History of African American Theatre Errol G. Hill and James V. Hatch Frontmatter More information AHistory of African American Theatre This is the first definitive history of African American theatre. The text embraces awidegeographyinvestigating companies from coast to coast as well as the anglo- phoneCaribbean and African American companies touring Europe, Australia, and Africa. This history represents a catholicity of styles – from African ritual born out of slavery to European forms, from amateur to professional. It covers nearly two and ahalf centuries of black performance and production with issues of gender, class, and race ever in attendance. The volume encompasses aspects of performance such as minstrel, vaudeville, cabaret acts, musicals, and opera. Shows by white playwrights that used black casts, particularly in music and dance, are included, as are produc- tions of western classics and a host of Shakespeare plays. The breadth and vitality of black theatre history, from the individual performance to large-scale company productions, from political nationalism to integration, are conveyed in this volume. errol g. hill was Professor Emeritus at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire before his death in September 2003.Hetaughtat the University of the West Indies and Ibadan University, Nigeria, before taking up a post at Dartmouth in 1968.His publications include The Trinidad Carnival (1972), The Theatre of Black Americans (1980), Shakespeare in Sable (1984), The Jamaican Stage, 1655–1900 (1992), and The Cambridge Guide to African and Caribbean Theatre (with Martin Banham and George Woodyard, 1994); and he was contributing editor of several collections of Caribbean plays. -

Mcmahon EC.Pdf

1992 Junior Bird Tournament Extra Credit Questions by · Col.l.een McMahon 46. 25 points By now everyone should be somewhat familiar with the crop of presidential hopefuls who went stumping in New Hampshire. All together, 62 candidates filed for this primary. See how many of these lesser-known politicos you can identify, for 5 points each: a. She is the candidate for the New Alliance Party, as she was in 1988. Lenora Fulani b. This tv comedian has run several times and is doing so again this year in spite of bankruptcy. Pat Paulsen c. The "wild-eyed libertarian" sent his form in from the federal prison where he is serving a term for mail fraud. Lyndon LaRouche d. He played Billy Jack in the 1970s movies; now he wants to follow in the footsteps of another movie star-turned-president. Tom Laughlin e. It just wouldn't be an election year without this candidate, the 84-year-old former governor of Minnesota, who has been running unsuccessfully since 1944. Harold Stassen 47. 20 points Identify these famous mythological wives, given the names of their husbands, for 5 points each: a. Agamemnon Clytemnestra b. Odysseus Penelope c. Oedipus Jocasta d. Priam Hecuba 48. 30 points Art Nouveau was an early 20th Century movement whose influences spread from painting to jewelry and furniture design. For 10 points each, identify these artists associated with Art Nouveau: a. Austrian, foremost practitioner of Art Nouveau in Vienna, works include The Kiss: Gustav Klimt b. His New York City studios specialized in favrile glasswork, characterized by iridescent colors. -

Newsletter Still Doesn't Have Any Reporting on Direct Queries and Submissions To: Recent Developments in U.S

N ewsletter NoVEMbER, 1991 VolUME 5 NuMbER 5 SpEciAl JournaL Issue In This Issue................................................................ 2 The Speed of DAnksess ancI "CrazecJ V ets on tHe oorstep rama e o s e PublJshER's S tatement, by Ka U TaL .............................5 D D ," by DAvId J. D R ...............40 REMF Books, by DAvid WHLs o n .............................. 45 A nnouncements, Notices, & Re p o r t s ......................... 4 eter C ortez In DarIen, by ALan FarreU ........................... 22 PoETRy, by P D ssy............................................4 4 FIctIon: Hie Romance of Vietnam, VoIces fROM tHe Past: TTie SearcTi foR Hanoi HannaK by RENNy ChRlsTophER...................................... 24 by Don NortTi ...................................................44 A FiREbAlL In tBe Nlqlrr, by WHUam M. KiNq...........25 H ollyw ood CoNfidENTlAl: 1, b y FREd GARdNER........ 50 Topics foR VJetnamese-U.S. C ooperation, PoETRy, by DennIs FRiTziNqER................................... 57 by Tran Qoock VuoNq....................................... 27 Ths A ll CWnese M ercenary BAskETbAll Tournament, Science FIctIon: This TIme It's War, by PauI OLim a r t ................................................ 57 by ALascIaIr SpARk.............................................29 (Not Much of a) War Story, by Norman LanquIst ...59 M y Last War, by Ernest Spen cer ............................50 Poetry, by Norman LanquIs t ...................................60 M etaphor ancI War, by GEORqE LAkoff....................52 A notBer -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

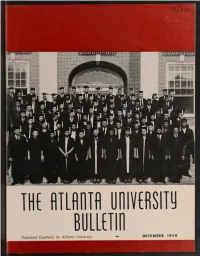

MMilt Published Quarterly by Atlanta University DECEMBER ■ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 3 Calendar 4 The New Music and Radio Center 6 The Annual Meeting of the As¬ sociation for the Study of Negro Life and History 8 Feature of the Issae French Graduates Lured hy Teaching 12 The 1950 Summer School 13 Sociology Department Con¬ ducts Post Health Survey 13 Private Library Bequeathed to University 14 The Conference on Library Ed¬ ucation AT OPENING OF MUSIC AND RADIO CENTER 17 Charter Day Is Observed (See Page 4) 18 Three Hundred Ninety - to assistant director Eight (Left right) Thomas Bernard, of public relations, RCA Are Enrolled in Graduate Victor; President Rufus E. Clement, of Atlanta Udiversity; James M. Toney, School director of public relations for RCA. 19 Spotlight 20 The Countee Cullen Memorial Collection 22 Graduate Degrees Awarded to 99 at Summer Convocation 23 Sidelines 24 Faculty Items 27 Alumni News 29 Requiescat in Pace 31 A Letter to Alumni and Friends from the President of the University Cover: Summer Graduating Class. 1950 Series III DECEMBER 1950 No. 72 Entered as second-class matter February 28, 1935, at the Post Office at Atlanta, Georgia, under the Act of August 24, 1912. Acceot- ance for mailing at special rate of postage provided for in the Act of February 28, 1925, 538, P. L. 4 H. 2 CALENDAR CHARTER DAY CONVOCATION: October 16 —Dr. Subject: “Integration of Undergraduate Pro¬ Charles S. Johnson. President of Fisk University grams with Graduate Programs in Library Ser¬ Subject: “Coming of Age” vice" CHARTER DAY DINNER: October 16 —Honoring CLOSING OF THE LIBRARY CONFERENCE: No¬ New Members of the Graduate Faculty vember 11 — Summary Delivered by Eric Moore. -

Travel Papers in American Literature

ROAD SHOW Travel Papers in American Literature This exhibition celebrates the American love of travel and adventure in both literary works and the real-life journeys that have inspired our most beloved travel narratives. Exploring American literary archives as well as printed and published works, Road Show reveals how travel is recorded, marked, and documented in Beinecke Library’s American collections. Passports and visas, postcards and letters, travel guides and lan- guage lessons—these and other archival documents attest to the physical, emotional, and intellectual experiences of moving through unfamiliar places, encountering new landscapes and people, and exploring different ways of life and world views. Literary manuscripts, travelers’ notebooks, and recorded reminiscences allow us to consider and explore travel’s capacity for activating the imagination and igniting creativity. Artworks, photographs, and published books provide opportunities to consider the many ways artists and writers transform their own activities and human interactions on the road into works of art that both document and generate an aesthetic experience of journeying. 1-2 Luggage tag, 1934, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers 3 Langston Hughes, Mexico, undated, Langston Hughes Papers 4 Shipboard photograph of Margaret Anderson, Louise Davidson, Madame Georgette LeBlanc, undated, Elizabeth Jenks Clark Collection of Margaret Anderson 5-6 Langston Hughes, Some Travels of Langston Hughes world map, 1924-60, Langston Hughes Papers 7 Ezra Pound, Letter to Viola Baxter Jordan with map, 1949, Viola Baxter Jordan Papers 8 Kathryn Hulme, How’s the Road? San Francisco: Privately Printed [Jonck & Seeger], 1928 9 Baedeker Handbooks for Greece, Belgium and Holland, Paris, Berlin, Great Britain, various dates 10 H. -

Allen Rostron, the Law and Order Theme in Political and Popular Culture

OCULREV Fall 2012 Rostron 323-395 (Do Not Delete) 12/17/2012 10:59 AM OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 37 FALL 2012 NUMBER 3 ARTICLES THE LAW AND ORDER THEME IN POLITICAL AND POPULAR CULTURE Allen Rostron I. INTRODUCTION “Law and order” became a potent theme in American politics in the 1960s. With that simple phrase, politicians evoked a litany of troubles plaguing the country, from street crime to racial unrest, urban riots, and unruly student protests. Calling for law and order became a shorthand way of expressing contempt for everything that was wrong with the modern permissive society and calling for a return to the discipline and values of the past. The law and order rallying cry also signified intense opposition to the Supreme Court’s expansion of the constitutional rights of accused criminals. In the eyes of law and order conservatives, judges needed to stop coddling criminals and letting them go free on legal technicalities. In 1968, Richard Nixon made himself the law and order candidate and won the White House, and his administration continued to trumpet the law and order theme and blame weak-kneed liberals, The William R. Jacques Constitutional Law Scholar and Professor of Law, University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. B.A. 1991, University of Virginia; J.D. 1994, Yale Law School. The UMKC Law Foundation generously supported the research and writing of this Article. 323 OCULREV Fall 2012 Rostron 323-395 (Do Not Delete) 12/17/2012 10:59 AM 324 Oklahoma City University Law Review [Vol. 37 particularly judges, for society’s ills. -

2004 Annual Town Report of the Hudson Recreation Department

, Annual Report of the Town of Hudson, New Hampshire ~~ONNeW ~~ ~ s ~~ ;;e" ~ _ -.' ~rJ2 ::.;....~~- - - =- ~ .- I I" I ~ ~~ ,..-- .'~ :'""(\0 .c-:.;;o... =- . ~ ~PORA1~\) for the year ending . June 30, 2004 --------------------~ omCEHOURS Assessor Monday through Friday 8:00 am - 4:30 pm Community Development Monday through Friday 8:00 am - 4:30 pm (BuildinglZoningIPlanning) Engineering Monday through Friday 8:00 am - 4:30 pm , • Finance Monday through Friday 8:00 am - 4:30 pm \, Selectmenffown Administrator Monday through Friday 8:00 am - 4:30 pm [ Sewer UtilitylWater Utility Monday through Friday 8:00 am - 4:30 pm \ t Town Clerklfax Collector Monday through Friday 8:30 am - 4:30 pm , 1 Hills Memorial Lihrary Monday through Thurs. 9:00 am - 9:00 pm i Friday and Saturday 9:00 am - 5:00 pm \ SCHEDULE OF MEETINGS OF TOWN BOARDS AND COMMITl'EES I [ Selectmen 7:00 pm -- 2'" & 4" Tuesday of each month I I, (Town Hall) Budget Committee 7:30 pm -·3'" Thursday of each month I (Town Hall) I Cable Utility Committee 7:00 pm •• 3'" Tuesday of each month I (Town Hall) Conservation Commission 7:00 pm -- 3'" Monday of each month I (Town Hall) Library Trustees 6:00 pm -- 3'" Tuesday of each month iI (49 Ferry Street Annex) Recreation Committee 6:30 pm .- 2'" Thursday of each month (Recreation Center) 1 Planning Board 7:00 pm -- 1",2'" & 4" Wednesday of each month (Town Hall) I, Sewer Utility 7:00 pm -- 2'" Thursday of each month (Town Hall) I Zoning Board of Adjustment 7:30 pm -- 2'" & 41h Thursday of each month I (Town Hall) 1 • I Annual Report of the Town of Hudson, New Hampshire ~~ONN~~ ~~ ~ o~ ~~"0 ~ __ ,.;; - __ --.' r.P:c ~ o - . -

Archivists & Archives of Color Newsletter

~Archivists & Archives of Color Newsletter~ Newsletter of the Archivists and Archives of Color Roundtable Vol. 19 No. 2 Fall/Winter 2005 Message from the Co-Chair Greetings from the New Editor! By Teresa Mora By Paul Sevilla It was only a few months ago that SAA gathered in New I feel very excited to serve as the new editor of the AAC Orleans for its 69th Annual Meeting. Little did we know at newsletter. One of my goals is to bring to readers articles that the time that the area would soon be devastated by Hurricane are interesting, informative, and inspiring. With help and Katrina. Many of our AAC friends and colleagues were support from my assistant editor, Andrea, we shall ensure that affected by the hurricane that hit the gulf coast. Rebecca this newsletter continues to represent the voices of our diverse Hankins offered family shelter in Texas, and, in an article on membership. the next page, Brenda B. Square at the Amistad Research Center updates us on Tulane’s situation. We have all read I became a member of SAA in my first year as an MLIS reports of the damage, and our thoughts are with all those who student in the Department of Information Studies at UCLA. hail from the area, especially with our colleagues and the As one of the recipients of this year’s Harold T. Pinkett unique collections, which many of us had been so fortunate to Minority Student Award, I had the privilege of attending the just see. conference in New Orleans and meeting the members of AAC. -

Queering Black Greek-Lettered Fraternities, Masculinity and Manhood : a Queer of Color Critique of Institutionality in Higher Education

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2019 Queering black greek-lettered fraternities, masculinity and manhood : a queer of color critique of institutionality in higher education. Antron Demel Mahoney University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Africana Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Higher Education Commons, History of Gender Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mahoney, Antron Demel, "Queering black greek-lettered fraternities, masculinity and manhood : a queer of color critique of institutionality in higher education." (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3286. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3286 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUEERING BLACK GREEK-LETTERED FRATERNITIES, MASCULINITY AND MANHOOD: A QUEER OF COLOR CRITIQUE OF INSTITUTIONALITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION By Antron Demel Mahoney B.S.,