Enzyme Tunnels and Gates As Relevant Targets in Drug Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Proteasome: a Proteolytic Nanomachine of Cell Regulation and Waste Disposal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1695 (2004) 19–31 http://www.elsevier.com/locate/bba Review The proteasome: a proteolytic nanomachine of cell regulation and waste disposal Dieter H. Wolf *, Wolfgang Hilt Institut fu¨r Biochemie, Universita¨t Stuttgart, Pfaffenwaldring 55, 70569 Stuttgart, Germany Available online 26 October 2004 Abstract The final destination of the majority of proteins that have to be selectively degraded in eukaryotic cells is the proteasome, a highly sophisticated nanomachine essential for life. 26S proteasomes select target proteins via their modification with polyubiquitin chains or, in rare cases, by the recognition of specific motifs. They are made up of different subcomplexes, a 20S core proteasome harboring the proteolytic active sites hidden within its barrel-like structure and two 19S caps that execute regulatory functions. Similar complexes equipped with PA28 regulators instead of 19S caps are a variation of this theme specialized for the production of antigenic peptides required in immune response. Structure analysis as well as extensive biochemical and genetic studies of the 26S proteasome and the ubiquitin system led to a basic model of substrate recognition and degradation. Recent work raised new concepts. Additional factors involved in substrate acquisition and delivery to the proteasome have been discovered. Moreover, first insights in the tasks of individual subunits or subcomplexes of the 19S caps in substrate recognition and binding as well as release and recycling of polyubiquitin tags have been obtained. D 2004 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. -

Supplemental Methods

Supplemental Methods: Sample Collection Duplicate surface samples were collected from the Amazon River plume aboard the R/V Knorr in June 2010 (4 52.71’N, 51 21.59’W) during a period of high river discharge. The collection site (Station 10, 4° 52.71’N, 51° 21.59’W; S = 21.0; T = 29.6°C), located ~ 500 Km to the north of the Amazon River mouth, was characterized by the presence of coastal diatoms in the top 8 m of the water column. Sampling was conducted between 0700 and 0900 local time by gently impeller pumping (modified Rule 1800 submersible sump pump) surface water through 10 m of tygon tubing (3 cm) to the ship's deck where it then flowed through a 156 µm mesh into 20 L carboys. In the lab, cells were partitioned into two size fractions by sequential filtration (using a Masterflex peristaltic pump) of the pre-filtered seawater through a 2.0 µm pore-size, 142 mm diameter polycarbonate (PCTE) membrane filter (Sterlitech Corporation, Kent, CWA) and a 0.22 µm pore-size, 142 mm diameter Supor membrane filter (Pall, Port Washington, NY). Metagenomic and non-selective metatranscriptomic analyses were conducted on both pore-size filters; poly(A)-selected (eukaryote-dominated) metatranscriptomic analyses were conducted only on the larger pore-size filter (2.0 µm pore-size). All filters were immediately submerged in RNAlater (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX) in sterile 50 mL conical tubes, incubated at room temperature overnight and then stored at -80oC until extraction. Filtration and stabilization of each sample was completed within 30 min of water collection. -

B Number Gene Name Mrna Intensity Mrna

sample) total list predicted B number Gene name assignment mRNA present mRNA intensity Gene description Protein detected - Membrane protein membrane sample detected (total list) Proteins detected - Functional category # of tryptic peptides # of tryptic peptides # of tryptic peptides detected (membrane b0002 thrA 13624 P 39 P 18 P(m) 2 aspartokinase I, homoserine dehydrogenase I Metabolism of small molecules b0003 thrB 6781 P 9 P 3 0 homoserine kinase Metabolism of small molecules b0004 thrC 15039 P 18 P 10 0 threonine synthase Metabolism of small molecules b0008 talB 20561 P 20 P 13 0 transaldolase B Metabolism of small molecules chaperone Hsp70; DNA biosynthesis; autoregulated heat shock b0014 dnaK 13283 P 32 P 23 0 proteins Cell processes b0015 dnaJ 4492 P 13 P 4 P(m) 1 chaperone with DnaK; heat shock protein Cell processes b0029 lytB 1331 P 16 P 2 0 control of stringent response; involved in penicillin tolerance Global functions b0032 carA 9312 P 14 P 8 0 carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase, glutamine (small) subunit Metabolism of small molecules b0033 carB 7656 P 48 P 17 0 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase large subunit Metabolism of small molecules b0048 folA 1588 P 7 P 1 0 dihydrofolate reductase type I; trimethoprim resistance Metabolism of small molecules peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase), involved in maturation of b0053 surA 3825 P 19 P 4 P(m) 1 GenProt outer membrane proteins (1st module) Cell processes b0054 imp 2737 P 42 P 5 P(m) 5 GenProt organic solvent tolerance Cell processes b0071 leuD 4770 P 10 P 9 0 isopropylmalate -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110747 A1 Ramseier Et Al

US 200601 10747A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110747 A1 Ramseier et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 25, 2006 (54) PROCESS FOR IMPROVED PROTEIN (60) Provisional application No. 60/591489, filed on Jul. EXPRESSION BY STRAIN ENGINEERING 26, 2004. (75) Inventors: Thomas M. Ramseier, Poway, CA Publication Classification (US); Hongfan Jin, San Diego, CA (51) Int. Cl. (US); Charles H. Squires, Poway, CA CI2O I/68 (2006.01) (US) GOIN 33/53 (2006.01) CI2N 15/74 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: (52) U.S. Cl. ................................ 435/6: 435/7.1; 435/471 KING & SPALDING LLP 118O PEACHTREE STREET (57) ABSTRACT ATLANTA, GA 30309 (US) This invention is a process for improving the production levels of recombinant proteins or peptides or improving the (73) Assignee: Dow Global Technologies Inc., Midland, level of active recombinant proteins or peptides expressed in MI (US) host cells. The invention is a process of comparing two genetic profiles of a cell that expresses a recombinant (21) Appl. No.: 11/189,375 protein and modifying the cell to change the expression of a gene product that is upregulated in response to the recom (22) Filed: Jul. 26, 2005 binant protein expression. The process can improve protein production or can improve protein quality, for example, by Related U.S. Application Data increasing solubility of a recombinant protein. Patent Application Publication May 25, 2006 Sheet 1 of 15 US 2006/0110747 A1 Figure 1 09 010909070£020\,0 10°0 Patent Application Publication May 25, 2006 Sheet 2 of 15 US 2006/0110747 A1 Figure 2 Ester sers Custer || || || || || HH-I-H 1 H4 s a cisiers TT closers | | | | | | Ya S T RXFO 1961. -

Das Proteasomsystem

4. Literaturverzeichnis Apcher GS, Maitland J, Dawson S, Sheppard P, Mayer RJ (2004) The alpha4 and alpha7 subunits and assembly of the 20S proteasome. FEBS Lett. 569(1-3):211-6. Aki M, Shimbara N, Takashina M, Akiyama K, Kagawa S, Tamura T, Tanahashi N, Yoshimura T, Tanaka K, Ichihara A (1994) Interferon-gamma induces different subunit organizations and functional diversity of proteasomes. J Biochem (Tokyo) 115:257-269 Bienkowska JR, Hartman H, Smith TF. (2003) A search method for homologs of small proteins. Ubiquitin-like proteins in prokaryotic cells? Protein Eng. 16(12):897-904. Bochtler M, Ditzel L, Groll M, Hartmann C, Huber R (1999) The proteasome. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct, 28, 295-317. Bochtler M, Hartmann C, Song HK, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, Huber R (2000) The structures of HslU and the ATP-dependent protease HslU-HslV. Nature 403, 800-805. Branninigan JA, Dodson G, Duggleby HJ, Moody PC, Smith JL, Tomchick, DR, Murzin AG (1995) A protein catalytic framework with an N-terminal nucleophile is capable of self- activation. Nature 378:414–419 Braun BC, Glickman M, Kraft R, Dahlmann B, Kloetzel PM, Finley D, Schmidt M. (1999) The base of the proteasome regulatory particle exhibits chaperone-like activity. Nat Cell Biol. 1(4):221-6. Brotz-Oesterhelt H, Beyer D, Kroll HP, Endermann R, Ladel C, Schroeder W, Hinzen B, Raddatz S, Paulsen H, Henninger K, Bandow JE, Sahl HG, Labischinski H. (2005) Dysregulation of bacterial proteolytic machinery by a new class of antibiotics. Nat Med. 11(10):1082-7. Bukau, B. (1997) The heat shock response in Escherichia coli. -

Product Sheet Info

Product Information Sheet for NR-8063 Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida, Growth Conditions: “Two-Allele” Transposon Mutant Library, Media: Tryptic Soy Agar containing 0.1% L-cysteine and 10 µg/mL Plate 29 (tnfn1_pw060510p01) kanamycin Incubation: Catalog No. NR-8063 Temperature: 37°C Atmosphere: Aerobic with 5% CO2 Propagation: For research use only. Not for human use. 1. Scrape top of frozen well with a pipette tip and streak onto agar plate. Contributor: 2. Incubate the plate at 37°C for 24–48 hours. Colin Manoil, Ph.D., Professor of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington Citation: Acknowledgment for publications should read “The following Product Description: reagent was obtained through the NIH Biodefense and A comprehensive 16508-member transposon mutant library1 Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository, NIAID, of sequence-defined transposon insertion mutants of NIH: Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida, “Two-Allele” Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida, strain U112 was Transposon Mutant Library, Plate 29 (tnfn1_pw060510p01), prepared to allow the systematic identification of virulence NR-8063.” determinants and other factors associated with Francisella pathogenesis. Genes refractory to insertional inactivation Biosafety Level: 2 helped define the genes essential for viability of the Appropriate safety procedures should always be used with organism. this material. Laboratory safety is discussed in the following publication: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, To facilitate genome-scale screening using the mutant Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and collection, a “two-allele” single-colony purified sublibrary, Prevention, and National Institutes of Health. Biosafety in made up of approximately two purified mutants per gene, Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. -

Proteasomes and Their Associated Atpases: a Destructive Combination

Journal of Structural Biology 156 (2006) 72–83 www.elsevier.com/locate/yjsbi Review Proteasomes and their associated ATPases: A destructive combination David M. Smith a, Nadia Benaroudj b, Alfred Goldberg a,¤ a Harvard Medical School, Department of Cell Biology, 240 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA b Pasteur Institute, Unit of Bacterial Genetics and DiVerentiation, 25-28 rue du Dr. Roux, 75724 Paris Cedex 15, France Received 24 February 2006; received in revised form 19 April 2006; accepted 19 April 2006 Available online 8 May 2006 Abstract Protein degradation by 20S proteasomes in vivo requires ATP hydrolysis by associated hexameric AAA ATPase complexes such as PAN in archaea and the homologous ATPases in the eukaryotic 26S proteasome. This review discusses recent insights into their multistep mechanisms and the roles of ATP. We have focused on the PAN complex, which oVers many advantages for mechanistic and structural studies over the more complex 26S proteasome. By single-particle EM, PAN resembles a “top-hat” capping the ends of the 20S protea- some and resembles densities in the base of the 19S regulatory complex. The binding of ATP promotes formation of the PAN–20S com- plex, which induces opening of a gate for substrate entry into the 20S. PAN’s C-termini, containing a conserved motif, docks into pockets in the 20S’s ring and causes gate opening. Surprisingly, once substrates are unfolded, their translocation into the 20S requires ATP- binding but not hydrolysis and can occur by facilitated diVusion through the ATPase in its ATP-bound form. ATP therefore serves multiple functions in proteolysis and the only step that absolutely requires ATP hydrolysis is the unfolding of globular proteins. -

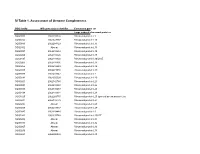

SI Table 1. Assessment of Genome Completeness

SI Table 1. Assessment of Genome Completeness COG family IMG gene object identifier Conserved gene set Large subunit ribosomal proteins COG0081 2062288324 Ribosomal protein L1 COG0244 2062347387 Ribosomal protein L10 COG0080 2062288323 Ribosomal protein L11 COG0102 Absent Ribosomal protein L13 COG0093 2062418832 Ribosomal protein L14 COG0200 2062418826 Ribosomal protein L15 COG0197 2062418838 Ribosomal protein L16/L10E COG0203 2062418836 Ribosomal protein L17 COG0256 2062418829 Ribosomal protein L18 COG0335 2062273558 Ribosomal protein L19 COG0090 2062418842 Ribosomal protein L2 COG0292 2062350539 Ribosomal protein L20 COG0261 2062142780 Ribosomal protein L21 COG0091 2062418840 Ribosomal protein L22 COG0089 2062138283 Ribosomal protein L23 COG0198 2062418834 Ribosomal protein L24 COG1825 2062269715 Ribosomal protein L25 (general stress protein Ctc) COG0211 2062142779 Ribosomal protein L27 COG0227 Absent Ribosomal protein L28 COG0255 2062418837 Ribosomal protein L29 COG0087 2062154483 Ribosomal protein L3 COG1841 2062335748 Ribosomal protein L30/L7E COG0254 Absent Ribosomal protein L31 COG0333 Absent Ribosomal protein L32 COG0267 Absent Ribosomal protein L33 COG0230 Absent Ribosomal protein L34 COG0291 2062350538 Ribosomal protein L35 COG0257 Absent Ribosomal protein L36 COG0088 2062138282 Ribosomal protein L4 COG0094 2062418833 Ribosomal protein L5 COG0097 2062418830 Ribosomal protein L6P/L9E COG0222 2062288326 Ribosomal protein L7/L12 COG0359 2062209880 Ribosomal protein L9 Small subunit ribosomal proteins COG0539 Absent Ribosomal protein -

The ATP-Dependent Codwx (Hslvu) Protease in Bacillus Subtilis Is an N-Terminal Serine Protease

The EMBO Journal Vol. 20 No. 4 pp. 734±742, 2001 The ATP-dependent CodWX (HslVU) protease in Bacillus subtilis is an N-terminal serine protease Min Suk Kang1, Byung Kook Lim1, Although Escherichia coli and other bacteria lack the Ihn Sik Seong1, Jae Hong Seol1,2, ubiquitin±proteasome pathway, they contain at least three Nobuyuki Tanahashi3, Keiji Tanaka3 and multimeric ATP-dependent proteases (Goldberg, 1992; Chin Ha Chung1,4 Chung, 1993; Gottesman, 1996; Chung et al., 1997). Rapid degradation of many abnormal polypeptides and various 1School of Biological Sciences, Seoul National University, regulatory proteins requires protease La (Lon), a heat Seoul 151-742, Korea and 3Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, CREST, Japan Science and Technology Corporation, shock protein composed of multiple but identical 87 kDa Tokyo 113, Japan subunits. This homopolymer has both serine active sites for proteolysis and ATP-cleaving sites in the same 2Present address: Division of Biology, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA polypeptide (Waxman and Goldberg, 1982; Menon and Goldberg, 1987). Unlike protease La, protease Ti (ClpAP) 4Corresponding author consists of two different multimeric components, both of e-mail: [email protected] which are required for proteolysis (Hwang et al., 1988). ClpA, which is composed of 84 kDa subunits, contains HslVU is a two-component ATP-dependent protease, ATP-hydrolyzing sites, while ClpP, which is composed of consisting of HslV peptidase and HslU ATPase. CodW 21 kDa subunits, is a serine protease. ClpA is a member of and CodX, encoded by the cod operon in Bacillus a family of highly conserved polypeptides, present in both subtilis, display 52% identity in their amino acid prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms (Gottesman et al., sequences to HslV and HslU in Escherichia coli, respectively. -

Structure of the Proteasome Tobias Jung and Tilman Grune

Structure of the Proteasome Tobias Jung and Tilman Grune Institute of Nutrition, Friedrich Schiller University, Jena, Germany I. Introduction .................................................................................. 1 II. The 20S Proteasome ........................................................................ 2 A. The Proteasomal a-Subunits ......................................................... 7 B. The Proteasomal b-Subunits ......................................................... 10 C. Intracellular Assembly of the 20S Proteasome ................................... 12 D. Modeling of the 20S Proteasomal Proteolysis .................................... 15 III. Regulation of the 20S Proteasome....................................................... 15 A. The 19S Regulator...................................................................... 16 B. The Immunoproteasome .............................................................. 16 C. The Thymus-Specific Proteasome (Thymoproteasome)........................ 19 D. The 11S Regulator...................................................................... 20 E. The Hybrid Proteasome (PA28–20S–PA700) ..................................... 21 F. The PA200 Regulator Protein ........................................................ 23 IV. Conclusion .................................................................................... 25 References .................................................................................... 26 The ubiquitin-proteasomal system is an essential element -

Downloaded from Supplemental Table S2 of the Original Paper (Nichols Et Al., 2011)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.16.206243; this version posted July 16, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 1 Title: Insights from the reanalysis of high-throughput chemical genomics data for 2 Escherichia coli K-12 3 Authors: Peter I-Fan Wu1, Curtis Ross1, Deborah A. Siegele2 and James C. Hu1,3 4 5 Affiliations: 6 1. Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Texas A&M University and Texas 7 Agrilife Research, College Station, TX 77843-2128 8 2. Department of Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-3258 9 3. Deceased 10 11 Correspondence: [email protected] 12 13 14 Key words: phenotypic profiling, functional genomics, microbial genomics, biostatistics, 15 Escherichia coli, bacterial genetics 16 17 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.16.206243; this version posted July 16, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 2 18 ABSTRACT 19 Despite the demonstrated success of genome-wide genetic screens and chemical 20 genomics studies at predicting functions for genes of unknown function or predicting 21 new functions for well-characterized genes, their potential to provide insights into gene 22 function hasn't been fully explored. -

Insight Into the Evolution of Microbial Metabolism from the Deep- 2 Branching Bacterium, Thermovibrio Ammonificans 3 4 5 Donato Giovannelli1,2,3,4*, Stefan M

1 Insight into the evolution of microbial metabolism from the deep- 2 branching bacterium, Thermovibrio ammonificans 3 4 5 Donato Giovannelli1,2,3,4*, Stefan M. Sievert5, Michael Hügler6, Stephanie Markert7, Dörte Becher8, 6 Thomas Schweder 8, and Costantino Vetriani1,9* 7 8 9 1Institute of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, 10 USA 11 2Institute of Marine Science, National Research Council of Italy, ISMAR-CNR, 60100, Ancona, Italy 12 3Program in Interdisciplinary Studies, Institute for Advanced Studies, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA 13 4Earth-Life Science Institute, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Tokyo 152-8551, Japan 14 5Biology Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA 15 6DVGW-Technologiezentrum Wasser (TZW), Karlsruhe, Germany 16 7Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Institute of Pharmacy, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-University Greifswald, 17 17487 Greifswald, Germany 18 8Institute for Microbiology, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-University Greifswald, 17487 Greifswald, Germany 19 9Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA 20 21 *Correspondence to: 22 Costantino Vetriani 23 Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology 24 and Institute of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences 25 Rutgers University 26 71 Dudley Rd 27 New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA 28 +1 (848) 932-3379 29 [email protected] 30 31 Donato Giovannelli 32 Institute of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences 33 Rutgers University 34 71 Dudley Rd 35 New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA 36 +1 (848) 932-3378 37 [email protected] 38 39 40 Abstract 41 Anaerobic thermophiles inhabit relic environments that resemble the early Earth. However, the 42 lineage of these modern organisms co-evolved with our planet.