G:\AT&T\272 Sunset\Verizon OI&M Forbearance\Exparte Final.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Affiliates

LIST OF AFFILIATES 33C Global Services, Inc, Furnishes telecommunications and systems integration products to customers and operates divisions which sell and service voice systems for business use. SBC International. Inc. Holding company for SBC subsidiaries and affiliates operating internationallywhose interests are in foreign telecommunications and other related businesses. SBC Internet Services, Inc. Internet service provider. SBC Laboratories, Inc. (FDC exception applies) Involved in applications research; the preparation of general generic specifications for products; the testing and evaluation of manutacturers' designs and products to determine if the general specification? set by the various SBC subsidiaries are being met; and writing applications software for computers with processing systems that have been designed to be user-programmed. SBC Long Distance, LLC (Section 272 Affiliate) Provides interexchange services. SBC Management Services, L.P. (FDC exception applies) Provides various administrative and support services for the parent holding company and other subsidiaries. SBC Management Services. USA, (FDC exception applies) Provides various administrative and support Inc. services for the parent holding company and other subsidiaries. SBC Operations, Inc. (FDC exception applies) Includes the development and design of business processes to provide for the planning, development and other support for the sale and merchandising of telecommunications services and products as well as a single point of contact for customers. SBC Services, Inc. (FDC exception applies) Performs centralized administrative support services including Information Technology and Billing Support Services, Real Estate Support Services, Procurement Support Services, Human Resources Support Services, Training Services and Finance Support Services. SBC Telecom, Inc. Competitive local exchange carrier. SNET America, Inc. lnterexchange service provider through carrier alliances. -

SBC Long Distance, LLC D/B/A SBC Long Distance D/B/A AT&T Long

SBC Long Distance, LLC South Carolina P.S.C. Tariff No. 9 d/b/a SBC Long Distance Original Title Page d/b/a AT&T Long Distance Local Exchange Services Tariff SBC LONG DISTANCE, LLC d/b/a SBC Long Distance d/b/a AT&T Long Distance RATES, RULES AND ADMINISTRATIVE REGULATIONS FOR FURNISHING LOCAL EXCHANGE SERVICES WITHIN THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA This Tariff (“Tariff”) is on file with the South Carolina Public Service Commission and may be inspected during normal working hours at the SBC Long Distance LLC, d/b/a SBC Long Distance, d/b/a AT&T Long Distance principal place of business, 1010 N. St. Mary’s, San Antonio, Texas 78215. "All references to SBC Long Distance, LLC, SBC Long Distance, Inc., Southwestern Bell Communications Services, Inc., SBC Long Distance, SBC Telecom, Inc. and AT&T Long Distance are to be considered interexchangeable for purposes of these tariff schedules Issued: December 19, 2005 Effective January 18, 2006 Issued by: Carol Paulsen, Director-Regulatory Relations 1010 N. St. Mary’s, Room 13-L San Antonio, Texas 78215 SBC Long Distance, LLC South Carolina P.S.C. Tariff No. 9 d/b/a SBC Long Distance 1st Revised Page 1 d/b/a AT&T Long Distance Local Exchange Services Tariff CHECK PAGE The pages of this Tariff are effective as of the date shown at the bottom of the respective page. Original and revised pages as named below comprise all changes from the original Tariff. PAGE REVISION PAGE REVISION PAGE REVISION Title Original 30 Original 60 Original 1 * Original 31 Original 61 Original 2 Original 32 Original 62 * 1st Revised -

Business Name D/B/A Name #1A LIFESAFER of COLORADO LLC

Business Name D/B/A Name #1A LIFESAFER OF COLORADO LLC 101 PARK AVENUE PARTNERS INC 1-800 CONTACTS INC 3 DAY BLINDS LLC 303 FURNITURE INC 303 TACTICAL LLC 303 TACTICAL 360 RAIL SERVICES LLC 3BB INC GREAT CLIPS 3D AUTOGLASS 3D STAINLESS LLC 3FORM LLC 3R Technology Solutions Inc 3SI SECURITY SYSTEMS INC 3T CULINARY INC THREE TOMATOES CATERING 4 FRONT ENGINEERED SOL INC 4283929 DELAWARE LLC ROCKY MTN PET CREMATION SERVICES 48FORTY SOLUTIONS LLC PALLET COMPANIES LLC 4imprint, Inc. 4LIFE RESEARCH CSA LLC 4LIFE RESEARCH USA LLC 50 IN 52 JOURNEY INC THE JOURNEY INSTITUTE 5071 INC 50-80 MASSAGE 5280 Contract Flooring 5280 HEATING COOLING & REFRIGERATION 5280 MAINTENANCE INC 5280 Stone Company, LLC 5280 Stone Company, LLC 5280 Telecom, LLC 5280 TOWING LLC 52Eighty Customs 5850 EAST 58TH AVENUE LLC 5850 EAST 58TH AVENUE LLC 6 ITALIAN WOLF SECURITY LLC 6171 LLC THE HIDEAWAY TAVERN 7-ELEVEN INC 7-ELEVEN STORE #38170 7-ELEVEN INC 7-ELEVEN STORE 37570 7-ELEVEN INC / JC INC 35828A 7-ELEVEN STORE 35828A 7-ELEVEN INC 23829 7-ELEVEN STORE 23829 7-ELEVEN INC 23829B 7-ELEVEN STORE 23829B 7-ELEVEN INC 34087 7-ELEVEN STORE 34087 7-ELEVEN INC 35828 7-ELEVEN STORE 35828 7-ELEVEN INC 35864 7-ELEVEN STORE 35864 7-ELEVEN INC 36013 7-ELEVEN STORE 36013 7-ELEVEN INC 36013 7-ELEVEN STORE 36013 7-ELEVEN INC 36464 7-ELEVEN STORE 36464 7-ELEVEN INC 36775 7-ELEVEN STORE 36775 7-ELEVEN INC 37291 7-ELEVEN STORE 37291 7-ELEVEN STORE 34087A 7-ELEVEN INC / S&As STORE INC 34087A 7-ELEVEN STORE 36013A EMHT INC & 7-ELEVEN INC 800-FLOWERS INC 8X8 INC A & A QUALITY APPLIANCE A & B Engineering Services LLC A CUSTOM COACH A CUT ABOVE LANDSCAPE LLC A GOOD LIL TRANNY SHOP LLC A GOOD SHOP INC A HOLE IN THE WALL CONSTRUCTIO AHW CONSTRUCTION A MAN WITH A VAN INC A SIMPLEE GORGEOUS BOUTIQUE A TO Z RENTAL CENTER, INC. -

LONG DISTANCE PROVIDERS Date Certified Complaints/Regulatory Matters To: Questions/Correspondence To: Reporting/Assessment Fees To: As of 1/22/09

LONG DISTANCE PROVIDERS Date Certified Complaints/Regulatory Matters To: Questions/Correspondence To: Reporting/Assessment Fees To: as of 1/22/09 1-800-RECONEX, Inc. d/b/a USTel 10/30/2003 800-973-9788 Anne Lynch, Regulatory Manager complaints to: Jeff Granger 2500 Industrial Avenue regulatory to: Anne Lynch Hubbard OR 97032 legal to: William Braun (503) 982-8000, 503-982-4539 fax 360networks (USA) inc. 8/25/2000 Terry Bate Julie R. Hawkins Jim Cox, Vice President of Operations 867 Coal Creek Circle, Suite 160 Louisville CO 80027 (303) 854-5000, (303) 854-5100 fax 3U Telecom, Inc. 9/30/2002 800-972-7538 Herve R. Andrieu 800-953-2938 fax 1802 N Carson Street, Suite 212-2683 Carson City NV 89701 (702) 260-4399, (702) 260-9143 fax 800 Response Information Services LLC 8/18/2005 800-639-1650 Stephanie Perrotte, Tariff Director 200 Church Street P O Box 2049 Burlington VT 05402 (802) 860-0378, (802) 860-0395 fax @link Networks, Inc. 2/23/2000 888-375-9750 Chapter 11 Bankruptcy -- Constance L. Kirkendall, Regulatory 5/10/2001 letter Manager 2220 Campbell Creek Blvd., Suite 110 Richardson TX 75082 (972) 367-1724, (214) 575-3026 ACN Communication Services, Inc. 3/25/2000 complaints to: Caroline Roberts, Vice President 887-226-1010 Business & Product Development Lance Beck 906-227-7402 32991 Halilton Court 906-346-5756 fax Farmington Hills MI 48333 411 Third Street (248) 699-4000, (248) 489-8837 fax Gwinn MI 79841 regulatory to: Lisa Lezotte 248-699-3314; 248-489-8615 fax IXC.Doc 1 LONG DISTANCE PROVIDERS Date Certified Complaints/Regulatory Matters To: Questions/Correspondence To: Reporting/Assessment Fees To: as of 1/22/09 AccessLine Communications Corporation 1/26/2005 877-716-2540 Ann Furuya, Compliance Officer Justin Bowers, Director of Small 11201 SE 8th Street, Suite 200 Business Sales Bellevue, WA 98004 (206) 621-3500, (206) 381-2299 fax Access One, Inc. -

ATTACHMENT 1 Foreign Carrier Affiliation Notification

AT&T Corp. Foreign Affiliation Notification Attachment 1 ATTACHMENT 1 Foreign Carrier Affiliation Notification Pursuant to Section 63.11 of the Commission’s rules, AT&T Corp. and the other U.S. international carrier affiliates of AT&T Inc. listed below (collectively, “AT&T”) hereby submit this foreign carrier affiliation notification for an affiliation with a newly licensed carrier in Mexico, AT&T Global Network Services Mexico, S. de R.L. de C.V. (“AT&T Mexico”). AT&T further informs the Commission that it no longer has an affiliation with Alestra, S. de R.L. de C.V., which is a foreign carrier in Mexico. The other U.S. international carrier affiliates of AT&T submitting this notification are: ACC National Long Distance Corp. Alascom, Inc. AT&T of Puerto Rico, Inc. AT&T of the Virgin Islands, Inc. BellSouth International, LLC BellSouth Long Distance, Inc. Centennial Communications Corp. SBC Long Distance, LLC SNET America, Inc. SNET Diversified Group, Inc. TCG America, Inc. TCG New Jersey, Inc. TC Systems, Inc. Answer to Question 10 These foreign carrier affiliation notifications do not result from an acquisition. AT&T Mexico received a license to provide basic telecommunications services to the public effective on July 18, 2011, and expects to begin providing such services in the near future. Answer to Questions 12 and 16 AT&T certifies that Mexico is a WTO member country.1 AT&T Mexico does not own facilities in Mexico. Pursuant to Section 63.10 of the Commission’s rules, 47 C.F.R. Sect. 63.10, the above-listed U.S. -

36005 Item Number

Control Number: 36005 Item Number: 1 Adde ndum StartPage: 0 AT&T Advanced Solutions August 15, 2008 Table of Contents ~ -° Docket No. AT&T Advanced Solutions Application to Amend Certificate of Operating Authority,-, COA No. 50026 Page 1. Letter of Notification 2 II. Application to Amend COA 3 III. Addendum I Attachment A - Organization Charts 62 IV. Addendum II Attachment B - Complaint Histories 213 IV. Addendum III Attachment C - Customer Data 489 V. Addendum IV Attachment D - 2007 10K Annual Report 490 VIII. Addendum V Attachment E - 2007 Annual Reports 1080 Texas Regulato ry AT&T Texas ~j 400 W. 15'h Street ~' ~}Q,} Room 950 `V~` Austin, TX 78701-1213 August 15, 2008 Commission Filing Clerk Public Utility Commission of Texas 1701 N. Congress Avenue Austin, TX 78701 Dear Filing Clerk: Re: AT&T Advanced Solutions Application to Amend Certificate of Operating Authority COA No. 50026 AT&T Advanced Solutions files with the Commission this application for approval of an amendment to its Certificate of Operating Authority due to a change in ownership/control and corporate restructuring. Questions or comments related to this matter may be directed to me at 512-870-6457. Sincerely, 0zi;za,XZUx,- Gina LaGrone Area Manager - Regulatory Relations Attachments cc: Commission on State Emergency Communications 2 AT&T Advanced Solutions AT&T Advanced Solutions APPLICATION FOR AMENDMENT TO A A CERTIFICATE OF OPERATING AUTHORITY DOCKET NO. CERTIFICATED APPLICANT: AT&T Advanced Solutions Authorized Representative or Attorney to contact about this Application: Gina LaGrone Area Manager - Regulatory Relations 400 W. 151 Street, Room 950 Austin, TX 78701 (512) 870-6457 (512) 870-1397 (fax) [email protected] Jose F. -

View Complaint

Case 1:11-cv-00338-LPS Document 12 Filed 03/29/12 Page 1 of 37 PageID #: 313 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE UNITED ACCESS § TECHNOLOGIES, LLC, § § Plaintiff, § § CIVIL ACTION NO. 1:11-cv-00338-LPS v. § § JURY TRIAL DEMANDED AT&T INC., § AMERITECH SERVICES, INC., § AT&T CORP., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § DELAWARE, LLC, § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § ILLINOIS, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § INDIANA, G.P., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § INDIANA, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § MICHIGAN, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF THE § MIDWEST, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF THE § MOUNTAIN STATES, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF NEW § YORK, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF NJ, § L.P., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § OHIO, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF THE § PACIFIC NORTHWEST, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § PENNSYLVANIA, LLC, § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF THE § SOUTH CENTRAL STATES, LLC, § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF THE § SOUTHERN STATES, LLC, § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF THE § SOUTHWEST, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § TEXAS, INC., § PAGE 1 Case 1:11-cv-00338-LPS Document 12 Filed 03/29/12 Page 2 of 37 PageID #: 314 AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § VIRGINIA, LLC, § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § WASHINGTON, D.C., LLC, § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § WISCONSIN, L.P., § AT&T OPERATIONS, INC., § AT&T SERVICES, INC., § AT&T TELEHOLDINGS, INC., § BELLSOUTH COMMUNICATION § SYSTEMS, LLC, § BELLSOUTH CORP., § BELLSOUTH § TELECOMMUNICATIONS, LLC, § ILLINOIS BELL TELEPHONE CO., § INDIANA BELL TELEPHONE CO., § INC., § MICHIGAN BELL TELEPHONE CO., § NEVADA BELL TELEPHONE -

Long Distance Calling, Focusing on Usage Patterns, Market Shares, Prices, and Expenditures

News media Information 202 / 418-0500 TTY: 202 / 418-2555 Fax-On-Demand 202 / 418-2830 Internet: http://www.fcc.gov NEWS ftp.fcc.gov Federal Communications Commission th 445 12 Street, S.W. Washington, D. C. 20554 This is an unofficial announcement of Commission action. Release of the full text of a Commission order constitutes official action. See MCI v. FCC. 515 F 2d 385 (D.C. Circ 1974). FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: NEWS MEDIA CONTACT: May 14, 2003 Michael Balmoris 202-418-0253 Email: [email protected] FCC RELEASES STATISTICS OF THE LONG DISTANCE TELECOMMUNICATIONS INDUSTRY REPORT Long Distance Market Revenue Declines; Average per Minute Rate Falls to 8 Cents per Minute Washington, D.C. – The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) today released its latest report on the long distance industry, Statistics of the Long Distance Telecommunications Industry. The report provides a general overview of the U.S. long distance telecommunications industry. The report is divided into two sections. The first section contains information that describes the total long distance market, such as revenues, market shares, and number of companies. The second section shows data on residential long distance calling, focusing on usage patterns, market shares, prices, and expenditures. Highlights from the report are shown below: I. Revenue Data In 2001, the long distance market had slightly more than $99 billion in revenues, compared to $110 billion in 2000. Carriers providing long distance service (including wireless carriers) accounted for over $90 billion and local telephone companies accounted for the remaining $9 billion; compared to $101 billion for long distance carriers and $9 billion for local telephone companies in 2000. -

AT&T Adoption Reimbursement Program

Program Important Benefits Information AT&T Adoption Reimbursement Program This booklet is your Program document for the AT&T Adoption Reimbursement Program. This Program document replaces the December 2002 SBC Adoption Reimbursement Program SPD and the SBC Adoption Reimbursement Program plan text in their entirety. DISTRIBUTION Distributed to management and bargained employees of all pre-merger SBC companies. NIN: 78-2420 Adoption Benefit Program | July 2006 IMPORTANT INFORMATION This Program document was written for easy readability. Therefore, it may contain generalizations and informal terms rather than precise legal terms. Also, this document is the official document of the Program. It will govern and be the final authority on the terms of the Program. AT&T reserves the right to terminate or amend any and all of its employee benefit plans or programs, subject to any collective bargaining obligation. Participation in this Program is neither a contract nor a guarantee of future employment. Please keep this Program document for future reference. This Program document is provided for your information and review; no other action is necessary. Table of Contents Page INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 4 ELIGIBILITY .............................................................................................................................. 4 CONTRIBUTIONS ..................................................................................................................... -

Current AHCF ID Numbers 6/1/2018

ID Carrier Name 2616 800 Response Information Services, LLC 3350 365 Wireless, LLC 3320 5LINX Enterprises, Inc.WRITEOFF 3280 1 800 Collect, Inc. cancelled 5/17 11-167-u 4365 2TalK, LLC 3240 AboveNet Communications, Inc. WRITEOFF 3080 Absolute Home Phones, Inc. 446 Access One 631 Access Point, Inc. 805 Access2Go, Inc. 2389 Accessline Communications Corporation 308 ACN Communications Services Inc. 3370 A C N Digital Phone Service 551 Advantage Telecommunications Corp 2676 Aero Communications, LLC cancelled 3/17 05-089-u 4370 Affilaited Technology Solutions, LLC 35 Affinity NetworK, Inc. 2990 Affordable Long Distance LLC 4020 AireCast, LLC 2883 Airespring, Inc. 399 AirNex Communications, Inc. cancelled 7/17 17-017-u 3520 AIO Wireless LLC 2978 ALEC,LLC 4430 Alianza, Inc 2981 Allegiance Communications WRITEOFF 830 Alliance Global NetworKs, LLC 677 Alliance Group Services, Inc. aka AGSI WRITEOFF Alliant TechnologiesAlliant Technologies 37 Alltel Cellular Associates of ArKansas 38 ALLTEL Central ArKansas Cellular 83 ALLTEL Comm of North ArKansas Cellular Ltd Partner 835 Alltel Communication Wireless Inc 307 Alltel Communication, Inc. 310 Alltel Communications of ArKansas RSA #12 CLP 84 Alltel Communications of Pine Bluff, LLC 85 Alltel Communications of Southwest AR Cellular Ltd 3860 AltaWorx, LLC. 2796 American Fiber NetworK, Inc. 811 American Messaging Services, Inc. 312 American Telecommunications Systems, Inc. 332 Americatel Corporation WRITEOFF 52 AmeriVision Communications Inc. dba Affinity4 4385 ANPI, Business, LLC 2980 ANXe Business 2822 Applewood Communications Corporation 838 Apptix, Inc. 394 ARC NetworKs, Inc. dba Info Highway 394 ARC NetworKs, Inc. dba Info Highway M - 3076 Aristotle Telecomm LLC - Not doing business 553 ArKansas iNet dba World Lynx, LLC 57 ArKansas RSA #1, Northern ArKansas WRITEOFF 58 ArKansas RSA #2, Searcy County Cellular Partnership 3 ArKansas Telephone Company, Inc. -

Current ARHCF Carriers and Addresses Only.Xlsx

3280 1 800 Collect, Inc. 3 3320 5LINX Enterprises, Inc. 2616 800 Response Information Services, LLC 12 3240 AboveNet Communications, Inc. 12 3080 Absolute Home Phones, Inc. 3 446 Access One 3 631 Access Point, Inc. 3 805 Access2Go, Inc. 3 2389 Accessline Communications Corporation 12 308 ACN Communications Services Inc. 3 551 Advantage Telecommunications Corp 12 2676 Aero Communications, LLC 12 35 Affinity Network, Inc. 12 2990 Affordable Long Distance LLC 3 2883 Airespring, Inc. 12 399 AirNex Communications, Inc. 12 2978 ALEC, Inc. 3 2981 Allegiance Communications 3 830 Alliance Global Networks, LLC 12 677 Alliance Group Services, Inc. aka AGSI 12 37 Alltel Cellular Associates of Arkansas 38 ALLTEL Central Arkansas Cellular 1 83 ALLTEL Comm of North Arkansas Cellular Ltd Partner 1 835 Alltel Communication Wireless Inc 3 307 Alltel Communication, Inc. 1 310 Alltel Communications of Arkansas RSA #12 CLP 1 84 Alltel Communications of Pine Bluff, LLC 85 Alltel Communications of Southwest AR Cellular Ltd 2796 American Fiber Network, Inc. 811 American Messaging Services, Inc. 312 American Telecommunications Systems, Inc. 12 332 Americatel Corporation 12 52 AmeriVision Communications Inc. dba Affinity4 12 2980 ANXe Business 12 2822 Applewood Communications Corporation 3 838 Apptix, Inc. 3 394 ARC Networks, Inc. dba Info Highway 394 ARC Networks, Inc. dba Info Highway 12 3076 Aristotle Telecomm LLC 3 553 Arkansas iNet dba World Lynx, LLC 12 57 Arkansas RSA #1, Northern Arkansas 1 58 Arkansas RSA #2, Searcy County Cellular Partnership 1 3 Arkansas Telephone Company, Inc. 1 29 Arkwest Communications, Inc. 1 3082 Assist Wireless, LLC 3 326 Association Administrators, Inc. -

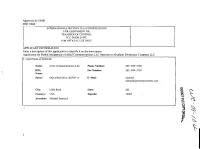

214 Authorizations Forassignment Or Transfer of Control Fcc Form214tc for Official Use Only

Approved by OMB 3060-0686 INTERNATIONAL SECTION 214 AUTHORIZATIONS FORASSIGNMENT OR TRANSFER OF CONTROL FCC FORM214TC FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY APPLICANT INFORMATION Enter a description of this application to identify it on the main menu: Application for Partial Assignment ofAlltel Communications, LLC Interests to Abraham Divestiture Company LLC 1. Legal Name ofApplicant Name: Alltel Communications, LLC Phone Number: 202-589-3768 DBA Fax Number: 202-589-3750 ~" Name: Street: One Allied Drive, B2F02-A E-Mail: michael. [email protected] City: Little Rock State: AR Country: USA Zipcode: 72202 § Attention: Michael Samsock on t ~ r::rn g ~ \J.. '-(\. ~ \ " m ; "'-~ ~ I 2. Name ofContact Representative Name: Nancy J. Victory Phone Number: 202-719-7344 Company: Wiley Rein LLP Fax Number: 202-719-7049 Street: 1776 K Street, NW E-Mail: [email protected] City: Washington State: DC Country: USA Zipcode: 20006- AUention: Nancy J. Victory Relationship: Legal Counsel CLASSIFICATION OF FILING 3.Choose the bUllon next to the classification that best describes this filing. Choose only one. @ a. Assignment ofSectio',' 214 Authority An Assignment ofan authorization is a transaction in which the authorization, or a portion ofit, is assigned from one entity to another. Following an assignment, the authorization will usually be held by an entity other than the one to which it was originally granted. (See Section 63.24(b).) o b. Transfer ofControl of Section 214 Authority A Transfer ofControl is a transaction"in which the authorization remains held by the same entity, but there is a change in the entity or entities that control the authorization holder. (See Section 63.24(c).) o c.