Rottnest Island Water Reserve Drinking Water Source Protection Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View the Rottnest Island Master Plan Here

A 20 yearROTTNEST ISLAND vision MASTER PLAN ria.wa.gov.au CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2 Master Plan Scope and Structure 3 2. THE SITE AND CONTEXT 4 3. THE PLACE 7 1. Main Settlement 8 2. Bathurst and Thomson Bay North 13 3. The Basin and Surrounds 17 4. Geordie and Longreach Bays 21 5. Thomson Bay South and the Airport Precinct 25 6. Kingstown and Bickley Point 28 7. Oliver Hill 32 8. Signal Ridge and Wadjemup Lighthouse 35 9. The Reserve 38 1 INTRODUCTION Rottnest Island has been a holiday and The sense of common ownership of the island is one recreation destination for the Western held dearly by Western Australians and has established Australian community since the early Rottnest as a low-key, low-impact and much-loved 1900s. This tradition continues today holiday destination. with a range of short-stay holiday Rottnest’s biggest challenge is to provide the range of accommodation available on the island, services, accommodation choices and visitor facilities complemented by extensive off-shore to meet the needs of visitors from WA and further mooring areas, camping grounds and a afield, while also protecting the natural environment small hub of commercial activity. and cultural heritage. Rottnest Island, or Wadjemup, has a rich social and There is great potential to enhance and protect the cultural history that adds greatly to visitors’ experience island landscape, while offering a wider choice of of the Island. holiday experiences to attract more visitors and to spread visitation more evenly throughout the year. Rottnest Island is located 18 kilometres off the coast More people staying longer in an environment that of Fremantle. -

Trade Guide Contents

WESTERN AUSTRALIA Trade Guide Contents Welcome to Rottnest Island 3 How to get to Rottnest Island 4 Visit all year round 5 A peaceful Class A nature reserve 5 Getting around 6 Rottnest Island’s top ten experiences 7 Accommodation 9 Dining and Refreshments 10 Internationally Ready Product 11 Rottnest Island business contacts 16 Rottnest Island map 18-19 All details correct at time of printing June 2021 2 Welcome to Rottnest Rottnest Island’s photogenic ambassador, Island the quokka, skyrocketed Western Australia’s favourite WESTERN AUSTRALIA’S island paradise to international fame PREMIER ISLAND ESCAPE! after high-profile celebrities including Roger Federer, Margot Robbie and Located less than 20 kilometres from Chris Hemsworth posted selfies with Western Australia’s world-renowned these cute, native marsupials on their port city of Fremantle, Rottnest Island social media channels. is an easily accessible nature No wonder quokkas are considered the lover’s paradise. happiest animals on Earth; they inhabit Rottnest Island is so close to Perth Australia’s most beautiful island. It’s easy that it’s visible from coastal vantage to see why our visitors love it here as points on clear days, which is much as they do. most often the case for Australia’s sunniest capital city. WESTERN Rottnest Island, or ‘Rotto’, as it’s AUSTRALIA affectionately known by locals, has been the destination of choice for Western Australians for generations, is also a “must see” destination for Hillarys people visiting Western Australia from interstate and overseas. Perth Rottnest Island Fremantle 3 How to get to Rottnest Island Hillarys 45 mins Rottnest Island’s pristine turquoise bays, Perth aquatic activities, walking trails, historic attractions and abundance of wildlife Rottnest Island 90 mins are just a short ferry ride from Perth, Fremantle or Hillarys Ferry Terminals. -

Full Day Pinnacles Desert Explorer With

PERTH WESTERN AUSTRALIA DAY TOURS & SHORT BREAKS Pinnacles Desert | Margaret River | Wave Rock | New Norcia Fremantle | Rottnest Island | Tree Top Walk | Wildflowers 2019/20 Edition 2 2 TOURING WITH ADAMS PINNACLE TOURS A wholly Western Australian owned company operating with over 37 years experience, ADAMS Pinnacle Tours is proudly regarded as Western Australia’s leading tour operator. Renowned for our custom-designed fleet of 5-star touring vehicles - visiting many of Western Australia’s premier and iconic attractions in superb comfort is made a reality. Five Star Luxury with ADAMS Pinnacle Tours Accommodation With Western Australia’s large distances, comfort For our longer tours into country areas, we’ve selected a should be part of your selection criteria. Our 5-star great range of comfortable properties for our overnight fleet of 10-50 seater coaches and 27 seater 4WDs are stays. Chosen for their friendly hospitality, quality regarded as one of Australia’s finest: accommodation standards, convenient locations and • 50% more legroom great food; these comfortable properties, combined • Extra-large reclining seats with seatbelts for safety with our spacious luxury coaches, will ensure you stay • Cosy sheepskin covers/leather seats and head rests refreshed and ready for the next day’s travel. • Headspace allowing fully upright standing • On-board restroom for long distances (27 seats or Delicious Food more) An important part of any holiday is great food and • Overhead air-conditioning, lighting and speakers we are proud to provide the very best meals including • Filtered hot and cold water dispenser gourmet platters on both our coach and 4WD tours. -

Rottnest-Island-Map-4.Pdf

HELLO & Welcome! STAYING ON THE ISLAND GETTING THERE THE SALT STORE 9 VISITOR CENTRE 2 Karma Rottnest Australia 8 Welcome to Perth! During your holiday, a visit to Rottnest Island is a must Select from a unique range of accommodation from budget to premium, There are three ferry operators that run ferry services to the island Heading to Rottnest Island this summer? Visit our new one-stop shop, Only a short walk from where you disembark the ferries near the Experience a unique heritage hotel in stunning Rottnest Island, Western do! The island holds a very special space in our hearts and there is no other ocean views, heritage listed cottages, quaint bungalows, cabins or from four locations: Perth, Fremantle (B Shed), Northport (10 minutes located within one of the Island’s most iconic historical buildings - the main jetty, the Visitor Centre’s helpful and friendly staff can assist in Australia. Secluded beaches, turquoise seas, storied history and the place like it in the world. Secluded and stunning bays to relax, sparkling campsites by visiting www.rottnestisland.com. You can also phone and1 from Fremantle) and Hillarys Boat Harbour; please see the Ferry Route Salt Store. Explore quality, locally made products showcasing the talent answering any questions you may have; information about attractions, friendliest marsupials you’ll ever meet: Rottnest Island is a unique offshore clear, blue water to swim, snorkle and dive, a safe, car free environment to discuss your needs by calling the reservation line on 9432 9111. The Map overleaf. Rottnest Express run services from Perth, Fremantle and of WA artists and artisans - perfect for souvenirs or gifts. -

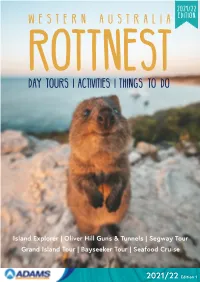

2021-2022 Rottnest Brochure

2021/22 western australia edition Rottnest day tours I ACTIVITIES I things to do Island Explorer | Oliver Hill Guns & Tunnels | Segway Tour Grand Island Tour | Bayseeker Tour | Seafood Cruise 2021/22 Edition 1 Rottnest island ferries Ferry Departure Points Departs: Daily from 7:00am Returns: Various Duration: Various Prices 01/04/2021-31/03/2022 Adult Concession Child Ferry transfers can be included and packaged into all tours. Prices vary depending on departure point and date of travel. Hillarys Boat Harbour From$88 From$78 From$49 Enquire when booking. Fremantle From$71 From$66 From$32.50 Perth From$109.50 From$104.50 From$52 Hillarys Boat Harbour PANTONE 389C PANTONE 306C North of Perth, Hillarys Boat Harbour is also home to the HILLARYS BOAT HARBOUR Aquarium of Western Australia, quaint shops and many restaurants. A free connecting courtesy shuttle, from Perth to PANTONE 389C the departure dock, is available upon request.* PANTONE 306C Ferry Operator: Rottnest Fast Ferries Courtesy Fremantle South of Perth, Fremantle is a bustling tourist destination, (25min)Bus packed with culture, history and eateries. The quickest ferry transfer to Rottnest Island, with two choices of ferry operators. Transfer Ferry Operators: Rottnest Express and SeaLink Perth In the heart of Perth City situated at Barrack Street Jetty. Enjoy a cruise along the Swan River before heading to Rottnest Island. Your choice of two ferry operators. 40 minutes PERTH Ferry Operators: Rottnest Express and SeaLink Hillarys Ex ROTTNEST ISLAND Ex Perth 1.5 hours Ex Fremantle 30 minutes FREMANTLE Note: Ferry fares include the Government Landing Fee. -

Download Groups Brochure

ROTTNEST EXPRESS GROUPS, CONFERENCES & INCENTIVES COMPANY PROFILE THE REGION GROUP BOOKINGS OUR LOCATIONS Rottnest Island sits just offshore Our group specialists are here to Rottnest Express has three ROTTNEST ISLAND IS ONE OF WA’S BEST KEPT from the city of Perth, in Western assist - no matter how large or small convenient locations, a daily morning SECRETS. BOASTING SPECTACULAR WHITE SANDY Australia. A protected nature reserve, your group may be. We can assist at departure from Elizabeth Quay BEACHES AND SECLUDED BAYS, THE ISLAND IS ALSO it’s famous for being the home to the any stage of the journey and design in Perth which runs non-stop to HOME TO UNIQUE WILDLIFE, INCLUDING THE FAMOUS quokka, a small wallaby-like marsupial. travel plans to match your specific Rottnest Island, B Shed Ferry QUOKKA. WITH AN EXTENSIVE RANGE OF FULLY White-sand beaches and secluded needs. We offer discounted ferry and Terminal which offers a number of ESCORTED OR SELF-GUIDED DAY TOURS TO CHOOSE coves include The Basin, with its tour options to all kinds of groups; departures every morning and is FROM, A VARIETY OF ON-ISLAND ACTIVITIES AND AN shallow waters, and Thomson Bay, the there are endless opportunities for just a 10-minute walk from the train ARRAY OF LUNCH OPTIONS, IT PROVIDES THE PERFECT main hub and ferry port. Strickland corporate, social and special interest station and the centre of Fremantle. DESTINATION FOR YOUR NEXT GROUP GETAWAY. Bay is known for its surf breaks, while groups to take their events to Also our Northport Ferry Terminal reef breaks occur at Radar Reef, off Rottnest. -

West Coast Australia 10

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd West Coast Australia Broome & the Kimberley p209 Ningaloo Coast & the Pilbara p187 Monkey Mia & the Central West p169 Perth Region p100 Perth p54 ^# Margaret River & the South Coast WA Southwest p125 p151 Charles Rawlings-Way, Fleur Bainger, Anna Kaminski, Tasmin Waby, Steve Waters PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to PERTH . 54 Swan Valley West Coast Australia . 4 Wine Region . 113 Sights . 56 Avon Valley . 115 West Coast Australia Activities . 66 Map . 6 Northam . 115 Tours . 72 West Coast Australia’s York . 116 Festivals & Events . 73 Top 13 . 8 Toodyay . 117 Sleeping . 75 Need to Know . 16 New Norcia . 118 Eating . 80 Wildflower Way . 118 First Time Drinking & Nightlife . 89 West Coast Australia . 18 Moora . 119 Entertainment . 93 What’s New . 20 Wongan Hills . 119 Shopping . 95 Accommodation . 22 Sunset Coast . 120 Guilderton . 120 Getting Around . 24 PERTH REGION . 100 Lancelin . 121 If You Like . 26 Rottnest Island . 102 Turquoise Coast . 121 Month by Month . 29 Rockingham . 106 Cervantes & Pinnacles Desert . 122 Itineraries . 32 Peel Region . 107 Mandurah . 107 Jurien Bay . 123 Discover Margaret River & the Southwest . 38 Dwellingup . 108 Green Head & Leeman . 124 West Coast Australia Perth Hills . 110 Outdoors . 42 Hyden & Wave Rock . 111 MARGARET Family Travel . 48 Swan Valley . 112 RIVER & THE Guildford . 112 SOUTHWEST . 125 Regions at a Glance . .. 51 Bunbury Geographe . 127 Bunbury . 127 DAVID STEELE/SHUTTERSTOCK © STEELE/SHUTTERSTOCK DAVID Busselton . 130 Margaret River Region . 131 Dunsborough . 131 CATHERINE SUTHERLAND/LONELY PLANET MAGAZINE © MAGAZINE PLANET SUTHERLAND/LONELY CATHERINE WAVE ROCK P111 ABORIGINAL SPEARHEAD, FITZROY CROSSING P231 Contents UNDERSTAND Cape Naturaliste . -

Rottnest Island IVV Permanent Trails: 6-10Km (Rated 1B-2B) (Wadjemup Bidi)

Rottnest Island IVV Permanent Trails: 6-10km (rated 1B-2B) (Wadjemup Bidi) Information extracted from http://trailswa.com.au/trails/networks/wadjemup-bidi-rottnest- island# and https://www.rottnestisland.com/see-and-do/natural-attractions/wadjemup-walk-trail - where you can download Fact Sheets for each section of the trail and get lots more information about your visit to Rottnest Island (or go to the Visitor’s Centre when you arrive). Rottnest Island is an A Class Nature Reserve, and is located just 19 kilometres off the coast of Fremantle. Transfers across to Rottnest Island can be booked through one of the two ferry operators. Rottnest Island ferry companies provide transfers to the island from Perth City, North Fremantle (Rous Head), Fremantle (Victoria Quay) and Hillarys Boat Harbour in Perth’s north. Rottnest ferries take approximately 25 minutes from Fremantle, 45 minutes from Hillarys Boat Harbour, or 90 minutes from Perth's Barrack Street Jetty. Accommodation is available on the island if you wish to stay overnight. Rottnest Island's famous marsupial, the Quokka, can be seen around the Island particularly in the mid to late afternoon. During the autumn and winter months (March to August) young joeys may be seen peeking from their mother’s pouch and by spring (September to November) they are hopping around. Don’t feed or touch the quokkas – on the spot fines apply! Please note: By downloading this document you acknowledge that you participate entirely at your own risk. Where possible, road crossings are at designated pedestrian crossing or traffic lights. At times parts of routes will be closed for maintenance and other reasons. -

A Taste of Western Australia Indian Pacific Departure Thursday

A TASTE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA INDIAN PACIFIC DEPARTURE THURSDAY Australia’s staggering diversity plays out on a grand scale as the Indian Pacific journeys from Perth to Adelaide. Add fine wine and regionally inspired meals to the mix, and this voyage really is a sensory indulgence. Before you experience the vast expanse of the Nullarbor Plain, get your holiday underway with explorations in Perth, Margaret River and beautiful Rottnest Island not far offshore. INCLUSIONS • 3 nights’ accommodation in Perth including breakfast daily • 1 day Discover Rottnest tour including lunch • 1 day Margaret River, Busselton Jetty & Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse tour • Transfer from hotel to East Perth Rail Terminal • 2 nights aboard the Indian Pacific, Perth to Adelaide including all meals, beverages and Off Train Experiences in Kalgoorlie, Rawlinna and Cook • 4 breakfasts, 4 lunches, 2 dinners HIGHLIGHTS • Explore the energetic, confident city of Perth, Australia’s sunniest capital • Cruise to Rottnest Island and meet a quokka • Experience the wineries, coastline and townships of Western Australia’s gorgeous Margaret River region • Ponder the vastness of the Australian continent as you cross the Nullarbor Plain • Sense the isolation in the remote desert outposts of Rawlinna and Cook DAY 1 PERTH Make your way to your Perth accommodation and prime yourself for a trip to Rottnest Island, a close encounter with the beautiful Margaret River region and an epic rail journey ahead. The evening is yours to embrace: discover some of the city’s atmospheric laneway bars and restaurants, buzzing with live music and street art. OVERNIGHT: 3 nights Double Tree By Hilton Perth Waterfront DAY 2 ROTTNEST ISLAND Make your way to Barrack Street Jetty and board the Rottnest Express to unique, diverse Rottnest Island, 22km offshore. -

7 Day a Taste of Western Australia

7 DAY A TASTE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA DESTINATIONS — ADELAIDE SYDNEY The information provided in this document is subject to change and may be affected by unforeseen events outside the control of Inspiring Vacations. Where changes to your itinerary or bookings occur, appropriate advice or instructions will be sent to your email address. Call 0800 475 025 Email [email protected] www.inspiringvacations.com TOUR ITINERARY DAY 1 Destination Perth Meals included Hotel 4 Pan Pacific Perth, or similar Make your way to your Perth accommodation and prime yourself for a trip to Rottnest Island, a close encounter with the beautiful Margaret River region and an epic rail journey ahead. The evening is yours to embrace: discover some of the city’s atmospheric laneway bars and restaurants, buzzing with live music and street art. DAY 2 Destination Perth Rottnest Island Meals included Breakfast, Lunch Hotel 4 Pan Pacific Perth, or similar Make your way to Barrack Street Jetty and board the Rottnest Express to unique, diverse Rottnest Island, 22km offshore. A 90-minute air-conditioned coach tour around ‘Rotto’ takes you to some spectacular locations, including Wadjemup Lighthouse and the boardwalk lookout at the rugged West End. Enjoy a delicious lunch at Karma Rottnest Lodge before exploring the island at your leisure (make sure you see a quokka). Return to Perth by ferry in the afternoon. DAY 3 Destination Perth Margaret River Perth Meals included Breakfast, Lunch Hotel 4 Pan Pacific Perth, or similar Travel south today and head towards the iconic Busselton Jetty, the world’s longest timber jetty (1841m). -

Signal Station

YOUR VIRTUAL DISCOVERY VISIT – 48 TO THE HERITAGE STORIES OF ROTTNEST ISLAND The Virtual Visit series was initiated during the COVID-19 pandemic when Rottnest Island was closed to the public due to social distancing restrictions and periods of use for quarantine from March to June 2020. Now that the Island is again open to visitors, these Virtual Visits are continuing in 2021 to enable a further enjoyment of stories introduced at the Wadjemup Museum, the Chapman Archives or sites around the Island. Enjoy, reflect and share. SITE EVOLUTION – WADJEMUP HILL SIGNAL STATION When the last pilot left Rottnest Island in 1903, a continuous record of more than 55 years of piloting ended. A new system was established with a signal station set up near Bathurst Lighthouse for the Fremantle Harbour Trust. The intent was for this station to observe requests for pilots from incoming vessels. Once a vessel was sighted, the news was telephoned to the lighthouse in Fremantle and the new, steam- powered pilot boat dispatched from there. Time Ball and Lighthouse at Arthur Head, Fremantle The Bathurst location proved adequate for vessels approaching from the North, but the topography of the Island prevented adequate observation for vessels approaching from the South. This was shown on the evening of 21 November 1903 when the barque River Indus stood of the Island by the South Passage. In the morning, when no pilot had appeared, the River Indus proceeded through the South Passage without a pilot. She struck a reef but without serious damage and docked at Fremantle. As a result of this incident, the Signal Station was dismantled in 1904 and re-erected near Wadjemup lighthouse in a location which offered 360 degree visibility. -

A Taste of Western Australia

A TASTE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA INDIAN PACIFIC DAY 2 – INDIAN PACIFIC, NULLARBOR PLAIN DEPARTURE THURSDAY Wake to breakfast as you begin your crossing of the Nullarbor Plain, taking its name from the Latin word Australia’s staggering diversity plays out on a grand scale as meaning ‘no trees’. Part way along the world’s longest the Indian Pacific journeys from Adelaide to Perth. Add fine stretch of straight railway track (478km), have a wander wine and regionally inspired meals to the mix, and this around Cook, an abandoned railway town once home to a voyage really is a sensory indulgence. Experience the vast bush hospital and more than 50 railway workers expanse of the Nullarbor Plain and further enrich your maintaining the tracks. Next stop is tiny Rawlinna, a remote holiday with explorations in Perth, Margaret River and outpost bordering the largest sheep station in the southern beautiful Rottnest Island not far offshore. hemisphere. Here you’ll enjoy an outback dinner under a glorious spread of stars (seasonal). (B,L,D) INCLUSIONS • 2 nights aboard the Indian Pacific, Adelaide to Perth DAY 3 – INDIAN PACIFIC, PERTH including all meals and beverages and Off Train Watch the delightful Avon Valley pass, whilst the final stage Experiences in remote Cook and Rawlinna of this transcontinental crossing unfolds. Enjoy a delightful • Transfer from East Perth Rail Terminal to hotel lunch as you head to your destination of Perth, arriving • 3 nights’ accommodation in Perth including breakfast mid-afternoon and transfer to your accommodation. The daily evening is yours to embrace: discover some of the city’s • 1 day Discover Rottnest tour including lunch atmospheric laneway bars and restaurants, buzzing with • 1 day Margaret River, Busselton Jetty & Cape Leeuwin live music and street art.