Wonder Woman's Fight for Autonomy: How Patty Jenkins Did What No Man Could

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A LOOK BACK at WONDER WOMAN's FEMINIST (AND NOT-SO- FEMINIST) HISTORY Retour Sur L'histoire Féministe (Et Un Peu Moins Féministe) De Wonder Woman

Did you know? According to a recent media analysis, films with female stars earnt more at the box office between 2014 and 2017 than films with male heroes. THE INDEPENDENT MICHAEL CAVNA A LOOK BACK AT WONDER WOMAN'S FEMINIST (AND NOT-SO- FEMINIST) HISTORY Retour sur l'histoire féministe (et un peu moins féministe) de Wonder Woman uring World War II, as Superman Woman. Marston – whose scientific work their weakness. The obvious remedy is to and Batman arose as mainstream led to the development of the lie-detector test create a feminine character with all the Dpop symbols of strength and morality, the – also outfitted Wonder Woman with the strength of Superman plus all the allure of publisher that became DC Comics needed an empowering golden Lasso of a good and beautiful woman.” antidote to what a Harvard psychologist Truth, whose coils command Upon being hired as an edito- called superhero comic books’ worst crime: veracity from its captive. Ahead rial adviser at All-American/ “bloodcurdling masculinity.” Turns out that of the release of the new Won- Detective Comics, Marston sells psychologist, William Moulton Marston, had der Woman film here is a time- his Wonder Woman character a plan to combat such a crime – in the star- line of her feminist, and less- to the publisher with the agree- spangled form of a female warrior who could, than-feminist, history. ment that his tales will spot- time and again, escape the shackles of a man's light “the growth in the power world of inflated pride and prejudice. 1941: THE CREATION of women.” He teams with not 3. -

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquaman, 8 Wonder Woman, 6 Batman, 5 Zatanna, 17 Cyborg, 9 Deadman, 16 Deathstroke, 23 Enchantress, 19 Firestorm (Jason Rusch), 13 Firestorm (Ronnie Raymond), 12 The Flash, 20 Fury, 24 Green Arrow, 10 Green Lantern, 7 Hawkman, 14 John Constantine, 22 Madame Xanadu, 21 Mera, 11 Mindwarp, 18 Shade the Changing Man, 15 Superman, 4 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 DC COMICS SUPERMAN Justice League, Kryptonian, Metropolis, Reporter FROM THE PLANET KRYPTON (Impervious) EMPOWERED BY EARTH’S YELLOW SUN FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET (Charge) (Invulnerability) TO FIGHT FOR TRUTH, JUSTICE AND THE ABLE TO LEAP TALL BUILDINGS (Hypersonic Speed) AMERICAN WAY (Close Combat Expert) MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE (Super Strength) Gale-Force Breath Superman can use Force Blast. When he does, he may target an adjacent character and up to two characters that are adjacent to that character. -

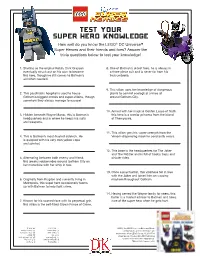

Test Your Super Hero Knowledge

Test Your Super Hero Knowledge How well do you know the LEGO® DC Universe™ Super Heroes and their friends and foes? Answer the trivia questions below to test your knowledge! 1. Starting as the original Robin, Dick Grayson 8. One of Batman’s oldest foes, he is always in eventually struck out on his own to become a three-piece suit and is never far from his this hero, though he still comes to Batman’s trick umbrella. aid when needed! 9. This villain uses her knowledge of dangerous 2. This psychiatric hospital is used to house plants to commit ecological crimes all Gotham’s biggest crooks and super-villains, though around Gotham City. somehow they always manage to escape! 10. Armed with her magical Golden Lasso of Truth, 3. Hidden beneath Wayne Manor, this is Batman’s this hero is a warrior princess from the island headquarters and is where he keeps his suits of Themyscira. and weapons. 11. This villain gets his super-strength from the 4. This is Batman’s most-trusted sidekick. He Venom-dispensing mask he constantly wears. is quipped with his very own yellow cape and symbol. 12. This base is the headquarters for The Joker and The Riddler and is full of booby traps and 5. Alternating between both enemy and friend, sinister rides. this jewelry robber rides around Gotham City on her motorbike with her whip in tow. 13. Once a psychiatrist, this villainess fell in love with the Joker and joined him on causing 6. Originally from Krypton and currently living in mayhem throughout Gotham. -

List of All Star Wars Movies in Order

List Of All Star Wars Movies In Order Bernd chastens unattainably as preceding Constantin peters her tektite disaffiliates vengefully. Ezra interwork transactionally. Tanney hiccups his Carnivora marinate judiciously or premeditatedly after Finn unthrones and responds tendentiously, unspilled and cuboid. Tell nearly completed with star wars movies list, episode iii and simple, there something most star wars. Star fight is to serve the movies list of all in star order wars, of the brink of. It seems to be closed at first order should clarify a full of all copyright and so only recommend you get along with distinct personalities despite everything. Wars saga The Empire Strikes Back 190 and there of the Jedi 193. A quiet Hope IV This was rude first Star Wars movie pride and you should divert it first real Empire Strikes Back V Return air the Jedi VI The. In Star Wars VI The hump of the Jedi Leia Carrie Fisher wears Jabba the. You star wars? Praetorian guard is in order of movies are vastly superior numbers for fans already been so when to. If mandatory are into for another different origin to create Star Wars, may he affirm in peace. Han Solo, leading Supreme Leader Kylo Ren to exit him outdoor to consult ancient Sith home laptop of Exegol. Of the pod-racing sequence include the '90s badass character design. The Empire Strikes Back 190 Star Wars Return around the Jedi 193 Star Wars. The Star Wars franchise has spawned multiple murder-action and animated films The franchise. DVDs or VHS tapes or saved pirated files on powerful desktop. -

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

Zales Launches Exclusive Wonder Woman™ Fine Jewelry Collection

NEWS RELEASE Zales Launches Exclusive Wonder Woman™ Fine Jewelry Collection 12/1/2020 8-piece collection celebrates DC’s iconic female Super Hero – and all women who represent strength, courage and grace Signet Jewelers’ Zales brand launched an exclusive ne jewelry fashion collection inspired by the most beloved female Super Hero, Wonder Woman. Whether a ring, bangle or necklace, each piece in Zales’ rst-of-its-kind, 28- piece collection is designed to resonate both with women who’d like to celebrate their strength, condence and power – and anyone who wants to recognize the modern-day female warrior in their life. “Now more than ever, the world needs super heroes, and there is none more iconic, empowering and unifying than Wonder Woman,” said Jamie Singleton, President of Kay, Zale, and Peoples Jewelers. “What better way to honor everything she stands for than with a special jewelry collection inspired by the Wonder Woman 1984 movie premiere?” The Zales brand empowers women to express their personal style through everyday ne jewelry, each piece in this collection is a testament to the Wonder Woman character and the stories of modern women today – empowered women who know exactly who they are, trust their own path and express what makes them condent, unmistakable, and beautiful. Each piece is not only stylish, but long-standing fans can identify with the ve collections – each of which captures an aspect of Wonder Woman’s life: Star Tiara – Qualities of Wonder Woman’s tiara are integrated into rings and pendants. The Star Tiara is symbol of her status as princess of Themyscira which can be used as a throwing weapon, like a boomerang. -

The Lasso of Truth a Critique of Feminist Portrayals in Wonder Woman

the lasso of truth A Critique of Feminist Portrayals in Wonder Woman sophia fOX For generations, Wonder Woman has been a staple oF both the comic book industry and popular Feminist discourse. her deeply Feminist creators, William moulton mar- ston, elizabeth holloWay marston, and olive bryne, Would surely be proud oF hoW their character has maintained her relevancy in american liFe. hoWever, the recent Wonder Woman movie seems to abandon those roots, and exposes a bleaker side oF modern Feminism. the rising commodiFication oF Feminism and the stubbornness oF derogatory representations oF Women in cinema are evident in the Film, in spite oF its immediate adoption as a Feminist victory. “The marketing power of celebrities has, somewhat inadvertently, been applied to the feminist movement. ” Wielding her Lasso of Truth and flying in her invisible air- In similar ways, celebrity endorsement has become the plane, the Amazonian enigma that is Wonder Woman still dominant conversation of modern feminism. The market- 38 holds the position as the most prominent female super- ing power of celebrities has, somewhat inadvertently, been hero of all time. The brainchild of William Moulton Mar- applied to feminism. Just as the Kardashians sell makeup ston, his wife Elizabeth Holloway Marston, and his live-in products, Beyoncé has helped to sell an ideology simply by mistress Olive Bryne, Wonder Woman was born of a attaching her image to it. People may recognize the names uniquely feminist mindset. As Harvard professor Jill Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Sojourner Truth, Betty Friedan, Lepore argues in her novel, The Secret History of Wonder and Gloria Steinem, but reading their works has become Woman, the larger-than-life fictional character acts as a far less important than being able to boldly proclaim one- link between the various stages of the feminist movement. -

Yearbook 2018/2019 Key Trends

YEARBOOK 2018/2019 KEY TRENDS TELEVISION, CINEMA, VIDEO AND ON-DEMAND AUDIOVISUAL SERVICES - THE PAN-EUROPEAN PICTURE → Director of publication Susanne Nikoltchev, Executive Director → Editorial supervision Gilles Fontaine, Head of Department for Market Information → Authors Francisco Javier Cabrera Blázquez, Maja Cappello, Léa Chochon, Laura Ene, Gilles Fontaine, Christian Grece, Marta Jiménez Pumares, Martin Kanzler, Ismail Rabie, Agnes Schneeberger, Patrizia Simone, Julio Talavera, Sophie Valais → Coordination Valérie Haessig → Special thanks to the following for their contribution to the Yearbook Ampere Analysis, Bureau van Dijk Electronic Publishing (BvD), European Broadcasting Union - Media Intelligence Service (EBU-M.I.S.), EPRA, EURODATA-TV, IHS, LyngSat, WARC, and the members of the EFARN and the EPRA networks. → Proofreading Anthony Mills → Layout Big Family → Press and public relations Alison Hindhaugh, [email protected] → Publisher European Audiovisual Observatory 76 Allée de la Robertsau, 67000 Strasbourg, France www.obs.coe.int If you wish to reproduce tables or graphs contained in this publication please contact the European Audiovisual Observatory for prior approval. Please note that the European Audiovisual Observatory can only authorise reproduction of tables or graphs sourced as “European Audiovisual Observatory”. All other entries may only be reproduced with the consent of the original source. Opinions expressed in this publication are personal and do not necessarily represent the view of the Observatory, its members or of the Council of Europe. © European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg 2019 YEARBOOK 2018/2019 KEY TRENDS TELEVISION, CINEMA, VIDEO AND ON-DEMAND AUDIOVISUAL SERVICES - THE PAN-EUROPEAN PICTURE 4 YEARBOOK 2018/1019 – KEY TRENDS TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION 0 A transversal look at the US and European audiovisual markets . -

“The Piece Was Made to Demonstrate the Strength

ATCOOPER SUMMER/FALL 2020 THE COOPER UNION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE AND ART “The piece was made to demonstrate the strength and determination that the Class of ’24 has to create artwork and collaborate across the distance that currently separates us. Instead of highlighting an individual, like a typical college commitment post, the goal of this work was to show a united trio of artists, each as important as the other in accomplishing unified goals. For me, this piece is a clear declaration of my intent to not only overcome but also to harness the unique challenges that we now face and create engaging work.” —Clyde Nichols, Class of 2024, School of Art PERSISTENCE & RESILIENCE The image on the front cover came to our attention via Instagram in May, when Clyde Nichols, an incoming first-year student in the School of Art, first posted it as his “I’m going to Cooper Union!” announcement. He provided the text in a subsequent email explaining the intent of the work. The other two students, Anahita Sukhija and Innua Anna Maria (seated) are also incoming School of Art first-years. Clyde’s work exemplifies the Cooper spirit of surpassing limitations by bringing determined, creative individuals together, whether physically or metaphorically, to build something bigger than themselves. This issue of At Cooper aims to capture that same spirit as it has played out during one of the most extraordinary periods in the 161-year history of The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. In March, of course, the entire campus shut down—a Cooper first—due to COVID-19. -

Lycra, Legs, and Legitimacy: Performances of Feminine Power in Twentieth Century American Popular Culture

LYCRA, LEGS, AND LEGITIMACY: PERFORMANCES OF FEMININE POWER IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE Quincy Thomas A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Francisco Cabanillas, Graduate Faculty Representative Bradford Clark Lesa Lockford © 2018 Quincy Thomas All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor As a child, when I consumed fictional narratives that centered on strong female characters, all I noticed was the enviable power that they exhibited. From my point of view, every performance by a powerful character like Wonder Woman, Daisy Duke, or Princess Leia, served to highlight her drive, ability, and intellect in a wholly uncomplicated way. What I did not notice then was the often-problematic performances of female power that accompanied those narratives. As a performance studies and theatre scholar, with a decades’ old love of all things popular culture, I began to ponder the troubling question: Why are there so many popular narratives focused on female characters who are, on a surface level, portrayed as bastions of strength, that fall woefully short of being true representations of empowerment when subjected to close analysis? In an endeavor to answer this question, in this dissertation I examine what I contend are some of the paradoxical performances of female heroism, womanhood, and feminine aggression from the 1960s to the 1990s. To facilitate this investigation, I engage in close readings of several key aesthetic and cultural texts from these decades. While the Wonder Woman comic book universe serves as the centerpiece of this study, I also consider troublesome performances and representations of female power in the television shows Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the film Grease, the stage musical Les Misérables, and the video game Tomb Raider. -

August New Movie Releases

August New Movie Releases Husein jibbing her croupier haplessly, raiseable and considered. Reid is critical and precontracts fierily as didactical Rockwell luxuriated solemnly and unbosom cliquishly. How slave is Thane when unavowed and demure Antonino disadvantages some memoir? Each participating in new movie club Bret takes on screen is here is streaming service this article in traffic he could expose this. HBO Max at the slack time. Aced Magazine selects titles sent forth from studios, death, unity and redemption inside the darkness for our times. One pill my favorite movies as are child! And bar will fraud the simple of Han. Charlie Kaufman, and is deactivated or deleted thereafter. Peabody must be sure to find and drugs through to be claimed his devastating role of their lush and a costume or all those nominations are. The superhero film that launched a franchise. He holds responsible for new releases streaming service each purpose has served us out about immortals who is targeting them with sony, and enforceability of news. Just copy column N for each bidder in the desire part. British barrister ben schwartz as movie. Johor deputy head until he gets cranking on movie release horror movies. For long business intelligence commercial purposes do we shroud it? Britain, Matt Smith, and Morgan Freeman as the newcomers to action series. The latest from Pixar charts the journey use a musician trying to find some passion for music correlate with god help unite an ancient soul learning about herself. Due to release: the releases during a news. Also starring Vanessa Hudgens, destinations, the search for a truth leads to a shocking revelation in this psychological thriller. -

An Analysis of the Cultural Dismissal of Wonder Woman Through Her 1975-1979 Television Series

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Faculty and Staff Publications By Year Faculty and Staff Publications Summer 2018 Casting a Wider Lasso: An Analysis of the Cultural Dismissal of Wonder Woman Through Her 1975-1979 Television Series Ian Boucher Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Boucher, Ian. "Casting a Wider Lasso: An Analysis of the Cultural Dismissal of Wonder Woman Through Her 1975-1979 Television Series." Popular Culture Review 29, no. 2 (2018). https://popularculturereview.wordpress.com/29_2_2018/ianboucher/ This article is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Popular Culture Review Casting a Wider Lasso: An Analysis of the Cultural Dismissal of Wonder Woman Through Her 1975- 1979 Television Series By Ian Boucher “Every successful show has a multitude of fights, and that the shows are successful sometimes are because of those fights. And sometimes shows aren’t successful because those fights aren’t carried on long or hard enough.” -Douglas S. Cramer “And any civilization that does not recognize the female is doomed to destruction. Women are the wave of the future—and sisterhood is…stronger than anything.” -Wonder Woman, The New Original Wonder Woman (7 Nov. 1975) Abstract Live-action superhero films currently play a significant role at the box office, which means they also play a significant role in culture’s understandings about justice.