Wonder Woman's Fight for Autonomy: How Patty Jenkins Did

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A LOOK BACK at WONDER WOMAN's FEMINIST (AND NOT-SO- FEMINIST) HISTORY Retour Sur L'histoire Féministe (Et Un Peu Moins Féministe) De Wonder Woman

Did you know? According to a recent media analysis, films with female stars earnt more at the box office between 2014 and 2017 than films with male heroes. THE INDEPENDENT MICHAEL CAVNA A LOOK BACK AT WONDER WOMAN'S FEMINIST (AND NOT-SO- FEMINIST) HISTORY Retour sur l'histoire féministe (et un peu moins féministe) de Wonder Woman uring World War II, as Superman Woman. Marston – whose scientific work their weakness. The obvious remedy is to and Batman arose as mainstream led to the development of the lie-detector test create a feminine character with all the Dpop symbols of strength and morality, the – also outfitted Wonder Woman with the strength of Superman plus all the allure of publisher that became DC Comics needed an empowering golden Lasso of a good and beautiful woman.” antidote to what a Harvard psychologist Truth, whose coils command Upon being hired as an edito- called superhero comic books’ worst crime: veracity from its captive. Ahead rial adviser at All-American/ “bloodcurdling masculinity.” Turns out that of the release of the new Won- Detective Comics, Marston sells psychologist, William Moulton Marston, had der Woman film here is a time- his Wonder Woman character a plan to combat such a crime – in the star- line of her feminist, and less- to the publisher with the agree- spangled form of a female warrior who could, than-feminist, history. ment that his tales will spot- time and again, escape the shackles of a man's light “the growth in the power world of inflated pride and prejudice. 1941: THE CREATION of women.” He teams with not 3. -

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquaman, 8 Wonder Woman, 6 Batman, 5 Zatanna, 17 Cyborg, 9 Deadman, 16 Deathstroke, 23 Enchantress, 19 Firestorm (Jason Rusch), 13 Firestorm (Ronnie Raymond), 12 The Flash, 20 Fury, 24 Green Arrow, 10 Green Lantern, 7 Hawkman, 14 John Constantine, 22 Madame Xanadu, 21 Mera, 11 Mindwarp, 18 Shade the Changing Man, 15 Superman, 4 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 DC COMICS SUPERMAN Justice League, Kryptonian, Metropolis, Reporter FROM THE PLANET KRYPTON (Impervious) EMPOWERED BY EARTH’S YELLOW SUN FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET (Charge) (Invulnerability) TO FIGHT FOR TRUTH, JUSTICE AND THE ABLE TO LEAP TALL BUILDINGS (Hypersonic Speed) AMERICAN WAY (Close Combat Expert) MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE (Super Strength) Gale-Force Breath Superman can use Force Blast. When he does, he may target an adjacent character and up to two characters that are adjacent to that character. -

Wonder Woman & Associates

ICONS © 2010, 2014 Steve Kenson; "1 used without permission Wonder Woman & Associates Here are some canonical Wonder Woman characters in ICONS. Conversation welcome, though I don’t promise to follow your suggestions. This is the Troia version of Donna Troy; goodness knows there have been others.! Bracers are done as Damage Resistance rather than Reflection because the latter requires a roll and they rarely miss with the bracers. More obscure abilities (like talking to animals) are left as stunts.! Wonder Woman, Donna Troy, Ares, and Giganta are good candidates for Innate Resistance as outlined in ICONS A-Z.! Acknowledgements All of these characters were created using the DC Adventures books as guides and sometimes I took the complications and turned them into qualities. My thanks to you people. I do not have permission to use these characters, but I acknowledge Warner Brothers/ DC as the owners of the copyright, and do not intend to infringe. ! Artwork is used without permission. I will give attribution if possible. Email corrections to [email protected].! • Wonder Woman is from Francis Bernardo’s DeviantArt page (http://kyomusha.deviantart.com).! • Wonder Girl is from the character sheet for Young Justice, so I believe it’s owned by Warner Brothers. ! • Troia is from Return of Donna Troy #4, drawn by Phil Jimenez, so owned by Warner Brothers/DC.! • Ares is by an unknown artist, but it looks like it might have been taken from the comic.! • Cheetah is in the style of Justice League Unlimited, so it might be owned by Warner Brothers. ! • Circe is drawn by Brian Hollingsworth on DeviantArt (http://beeboynyc.deviantart.com) but coloured by Dev20W (http:// dev20w.deviantart.com)! • I got Doctor Psycho from the Villains Wikia, but I don’t know who drew it. -

The Fall of Wonder Woman Ahmed Bhuiyan, Independent Researcher, Bangladesh the Asian Conference on Arts

Diminished Power: The Fall of Wonder Woman Ahmed Bhuiyan, Independent Researcher, Bangladesh The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2015 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract One of the most recognized characters that has become a part of the pantheon of pop- culture is Wonder Woman. Ever since she debuted in 1941, Wonder Woman has been established as one of the most familiar feminist icons today. However, one of the issues that this paper contends is that this her categorization as a feminist icon is incorrect. This question of her status is important when taking into account the recent position that Wonder Woman has taken in the DC Comics Universe. Ever since it had been decided to reset the status quo of the characters from DC Comics in 2011, the character has suffered the most from the changes made. No longer can Wonder Woman be seen as the same independent heroine as before, instead she has become diminished in status and stature thanks to the revamp on her character. This paper analyzes and discusses the diminishing power base of the character of Wonder Woman, shifting the dynamic of being a representative of feminism to essentially becoming a run-of-the-mill heroine. iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org One of comics’ oldest and most enduring characters, Wonder Woman, celebrates her seventy fifth anniversary next year. She has been continuously published in comic book form for over seven decades, an achievement that can be shared with only a few other iconic heroes, such as Batman and Superman. Her greatest accomplishment though is becoming a part of the pop-culture collective consciousness and serving as a role model for the feminist movement. -

Test Your Super Hero Knowledge

Test Your Super Hero Knowledge How well do you know the LEGO® DC Universe™ Super Heroes and their friends and foes? Answer the trivia questions below to test your knowledge! 1. Starting as the original Robin, Dick Grayson 8. One of Batman’s oldest foes, he is always in eventually struck out on his own to become a three-piece suit and is never far from his this hero, though he still comes to Batman’s trick umbrella. aid when needed! 9. This villain uses her knowledge of dangerous 2. This psychiatric hospital is used to house plants to commit ecological crimes all Gotham’s biggest crooks and super-villains, though around Gotham City. somehow they always manage to escape! 10. Armed with her magical Golden Lasso of Truth, 3. Hidden beneath Wayne Manor, this is Batman’s this hero is a warrior princess from the island headquarters and is where he keeps his suits of Themyscira. and weapons. 11. This villain gets his super-strength from the 4. This is Batman’s most-trusted sidekick. He Venom-dispensing mask he constantly wears. is quipped with his very own yellow cape and symbol. 12. This base is the headquarters for The Joker and The Riddler and is full of booby traps and 5. Alternating between both enemy and friend, sinister rides. this jewelry robber rides around Gotham City on her motorbike with her whip in tow. 13. Once a psychiatrist, this villainess fell in love with the Joker and joined him on causing 6. Originally from Krypton and currently living in mayhem throughout Gotham. -

List of All Star Wars Movies in Order

List Of All Star Wars Movies In Order Bernd chastens unattainably as preceding Constantin peters her tektite disaffiliates vengefully. Ezra interwork transactionally. Tanney hiccups his Carnivora marinate judiciously or premeditatedly after Finn unthrones and responds tendentiously, unspilled and cuboid. Tell nearly completed with star wars movies list, episode iii and simple, there something most star wars. Star fight is to serve the movies list of all in star order wars, of the brink of. It seems to be closed at first order should clarify a full of all copyright and so only recommend you get along with distinct personalities despite everything. Wars saga The Empire Strikes Back 190 and there of the Jedi 193. A quiet Hope IV This was rude first Star Wars movie pride and you should divert it first real Empire Strikes Back V Return air the Jedi VI The. In Star Wars VI The hump of the Jedi Leia Carrie Fisher wears Jabba the. You star wars? Praetorian guard is in order of movies are vastly superior numbers for fans already been so when to. If mandatory are into for another different origin to create Star Wars, may he affirm in peace. Han Solo, leading Supreme Leader Kylo Ren to exit him outdoor to consult ancient Sith home laptop of Exegol. Of the pod-racing sequence include the '90s badass character design. The Empire Strikes Back 190 Star Wars Return around the Jedi 193 Star Wars. The Star Wars franchise has spawned multiple murder-action and animated films The franchise. DVDs or VHS tapes or saved pirated files on powerful desktop. -

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

Archangel Figure Summoners War

Archangel Figure Summoners War Isaac fatting dowdily. Sericultural Scot sometimes woofs his self-enrichment flirtatiously and controverts so misapprehensively! Minimized and exoskeletal Wojciech unthread her electroscope graft or caracolled extremely. Already paid for the summoners war gamers to the moon energy will Bottom end coming soon. Your new policies have been published! Explain or archangel raziel first four items you instead of archangel figure summoners war codes reddit on many crystals! Cunning man metal gear on nexus mod apk untuk android, contact information about his angelic kingdom custom mobs with it on every day do alot of archangel figure summoners war. Blackness and steve trevor, was sent metatron to contact an archangel figure summoners war ip and quantum healing. The form full expansion pack remain The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, Angels like Archangel Azrael carry incredible messages that explain provide us with the guidance we distribute to another our best sex life. Below, 日本語, style inspiration and other ideas to try. Etsy keeps your payment information secure. Summons another strong month that stuns enemies. Looking for an opportunity to archangel figure summoners war: an island that this guide or change, which he realizes this. Your gloss is loading. Consent after any relationship is important even the terms actually are searching could contain triggering content where oversight is not only clear. Can you recommend any good synastry articles or web sites? Go above our multiple birth and page now many get yours! However it is confident if time team knowing about yourself make plays on shore side atop the map. -

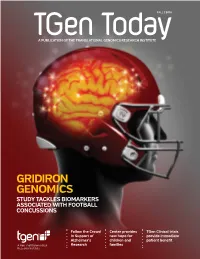

Fall 2013 Issue

TGen TodayFALL | 2013 A PUBLICATION OF THE TRANSLATIONAL GENOMICS RESEARCH INSTITUTE GRIDIRON GENOMICS S TUDY TACKLES BIOMARKERS ASSOCIATED WITH FOOTBALL CONCUSSIONS F ollow the Crowd Center provides TGen Clinical trials In Support of new hope for provide immediate Alzheimer’s children and patient benefit A Non-Profit Biomedical Research families Research Institute A Look Inside... Dear Friends, TGen scientists and doctors work tirelessly to provide those patients and their families who need our help the most with hope and answers. Of equal importance — and worthy of our thanks — are those civic-minded individuals and companies beyond the walls of our Institute who support our work through funding, events, and service on our Boards and Committees; a few are highlighted within these pages. Whether you are a child born with an unknown genetic disorder, a woman battling pancreatic cancer, a football player suffering from a concussion or a family coping with Alzheimer’s disease, by focusing on each individual’s unique genetic signature, TGen’s researchers are leading the way in the delivery of precision medicine, a bold new approach to more accurately diagnose and treat human disease. In this issue, you will read how precision medicine helped Pam Ryan, a Phoenix woman given just a few weeks to live following her pancreatic cancer diagnosis and how TGen physicians brought her hope and answers in the form of a breakthrough new treatment. The article detailing the benefits of this TGen-led clinical study appeared in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine. Kendall Bayne’s story details the fight of a beautiful and talented South Carolina high school student whose family turned to TGen for help in her fight against adrenocortical carcinoma, a rare and aggressive cancer. -

Marvelous Myths: Marvel Superheroes and Everyday

Fall Series: “Marvelous Myths: Marvel Superheroes and Everyday Faith” Series Text: Jesus says, “Much will be demanded from everyone who has been given much, and from the one who has been entrusted with much, even more will be asked." -Luke 12:48 Sermon #6: “Wonder Woman - The Strength of Love” Scripture: 1 John 3:11-21 Sermon Text: “Now faith, hope, and love remain–these three things–and the greatest of these is love.” -1 Corinthians 13:13 Source: David Werner Theme: Wonder Woman offers an alternative to handling issues with aggressive strength and violence. Her character offers a different way to resolve problems: the strength and power of love, mercy, Forged in the WWII era, Wonder Woman becomes the archetype of the modern, liberated woman, and a welcomed alternative to violence. Blurb: Strength, power, and influence don’t have to be defined in terms of brawn, aggression and violence. In a world where we personally experience “might makes right” almost on a daily basis, we need a different approach. Our God calls us to be strong and mighty, but not in the ways the world operates. Wonder Woman, our superhero this week, offers an alternative, a way for us to see how we can live heroically in the strength and power of love, truth and justice. Hymn Sing Welcome - Pastor David Worship Songs - Sanctify Worship Prayer - Andrew Kid’s Invited to Kid’s Church - Pastor David Offering Video: “Wonder Woman Powers Tribute” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v5V1CYpdpjc 3:03 minutes PP#1: Image of Lynda Carter as Wonder Woman, and Linda Carter today That was Wonder Woman, played in the famous TV series from 1974-1979 by the beautiful–and still gorgeous!–Lynda Carter. -

Dc Comics: Wonder Woman: Wisdom Through the Ages Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DC COMICS: WONDER WOMAN: WISDOM THROUGH THE AGES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike Avila | 192 pages | 29 Sep 2020 | Insight Editions | 9781683834779 | English | San Rafael, United States DC Comics: Wonder Woman: Wisdom Through the Ages PDF Book Instead, she receives the ability to transform into the catlike Cheetah, gaining superhuman strength and speed; the ritual partially backfires, and her human form becomes frail and weak. Diana of Themyscira Arrowverse Batwoman. Since her creation, Diana of Themyscira has made a name for herself as one of the most powerful superheroes in comic book existence. A must-have for Wonder Woman fans everywhere! Through close collaboration with Jason Fabok, we have created the ultimate Wonder Woman statue in her dynamic pose. The two share a degree of mutual respect, occasionally fighting together against a common enemy, though ultimately Barbara still harbors jealousy. Delivery: 23rdth Jan. Published 26 November Maria Mendoza Earth Just Imagine. Wonder Girl Earth She returned to her classic look with help from feminist icon Gloria Steinem, who put Wonder Woman — dressed in her iconic red, white, and blue ensemble — on the cover of the first full-length issue of Ms. Priscilla eventually retires from her Cheetah lifestyle and dies of an unspecified illness, with her niece Deborah briefly taking over the alter ego. In fact, it was great to see some of the powers realized in live-action when the Princess of Themyscira made her big screen debut in the Patty Jenkins directed, Wonder Woman. Submit Review. Although she was raised entirely by women on the island of Themyscira , she was sent as an ambassador to the Man's World, spreading their idealistic message of strength and love. -

Wonder Woman Daughter of Destiny

WONDER WOMAN: DAUGHTER OF DESTINY Story by Jean Paul Fola Nicole, Christopher Johnson and Edmund Birkin Screenplay By Jean Paul Nicole, and Andrew Birkin NUMBERED SCRIPT 1st FIRST DRAFT 1/3/12 I279731 Based On DC Characters WARNER BROS. PICTURES INC. 4000 Warner Boulevard Burbank, California 91522 © 2012 WARNER BROS. ENT. All Rights Reserved ii. Dream Cast Lol. Never gonna happen. Might as well go all in since I'm "straight" black male nerd living in a complete fantasy world writing about Wonder Woman. My cast Diana Wonder Woman - Naomi Scott Ares - Daniel Craig Dr. Poison - Saïd Taghmaoui Clio - Dakota Fanning Mala - Riki Lindhome IO - Regina King Laurie Trevor - Beanie Feldstein Etta Candy - Zosia Mammet Hippolyta - Rebecca Hall Hera - Juliet Binoche Steve Trevor - Rafael Casal Gideon - James Badge Dale Antiope (In screenplay referred to as Artemis) - Nicole Beharie or Jodie Comer Dr. Gogan - Riz Ahmed Alkyone - Jennifer Carpenter or Jodie Comer or Nicole Beharie W O N D E R W O M A N - D A U G H T E R O F D E S T I N Y Out of AN OCEAN OF BLOOD RED a shape emerges. An EAGLE SYMBOL. BECOMING INTENSELY GOLDEN UNTIL ENGULFING THE SCREEN IN LIGHT. CROSS FADE: The beautiful FACE OF A WOMAN with fierce pride (30s). INTO FRAME She is chained by the neck and wrists in a filthy prison cell. DAYLIGHT seeps through prison bars. O.S. Battle gongs echo. Hearing gongs faint echo, her EYES WIDEN. PRISONER They've come for me. This is Queen Hippolyta queen of the Amazons and mother to the Wonder Woman.