An Early Energy Crisis and Its Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climatic Variability in Sixteenth-Century Europe and Its Social Dimension: a Synthesis

CLIMATIC VARIABILITY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE AND ITS SOCIAL DIMENSION: A SYNTHESIS CHRISTIAN PFISTER', RUDOLF BRAzDIL2 IInstitute afHistory, University a/Bern, Unitobler, CH-3000 Bern 9, Switzerland 2Department a/Geography, Masaryk University, Kotlar8M 2, CZ-61137 Bmo, Czech Republic Abstract. The introductory paper to this special issue of Climatic Change sununarizes the results of an array of studies dealing with the reconstruction of climatic trends and anomalies in sixteenth century Europe and their impact on the natural and the social world. Areas discussed include glacier expansion in the Alps, the frequency of natural hazards (floods in central and southem Europe and stonns on the Dutch North Sea coast), the impact of climate deterioration on grain prices and wine production, and finally, witch-hlllltS. The documentary data used for the reconstruction of seasonal and annual precipitation and temperatures in central Europe (Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic) include narrative sources, several types of proxy data and 32 weather diaries. Results were compared with long-tenn composite tree ring series and tested statistically by cross-correlating series of indices based OIl documentary data from the sixteenth century with those of simulated indices based on instrumental series (1901-1960). It was shown that series of indices can be taken as good substitutes for instrumental measurements. A corresponding set of weighted seasonal and annual series of temperature and precipitation indices for central Europe was computed from series of temperature and precipitation indices for Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic, the weights being in proportion to the area of each country. The series of central European indices were then used to assess temperature and precipitation anomalies for the 1901-1960 period using trmlsfer functions obtained from instrumental records. -

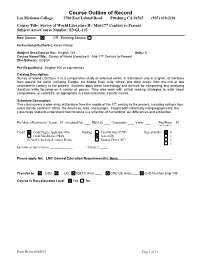

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181 Course Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Subject Area/Course Number: ENGL-145 New Course OR Existing Course Instructor(s)/Author(s): Karen Nakaji Subject Area/Course No.: English 145 Units: 3 Course Name/Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Discipline(s): English Pre-Requisite(s): English 100 or equivalency Catalog Description: Survey of World Literature II is a comparative study of selected works, in translation and in English, of literature from around the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other areas, from the mid or late seventeenth century to the present. Students apply basic terminology and devices for interpreting and analyzing literature while focusing on a variety of genres. They also work with critical reading strategies to write about comparisons, or contrasts, as appropriate in a baccalaureate, transfer course. Schedule Description: This class covers a wide array of literature from the middle of the 17th century to the present, including authors from every literate continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Taught both historically and geographically, the class helps students understand how literature is a reflection of humankind, our differences and similarities. Hrs/Mode of Instruction: Lecture: 54 Scheduled Lab: ____ HBA Lab: ____ Composition: ____ Activity: ____ Total Hours 54 (Total for course) Credit Credit Degree Applicable -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

A Concise Dictionary of Middle English

A Concise Dictionary of Middle English A. L. Mayhew and Walter W. Skeat A Concise Dictionary of Middle English Table of Contents A Concise Dictionary of Middle English...........................................................................................................1 A. L. Mayhew and Walter W. Skeat........................................................................................................1 PREFACE................................................................................................................................................3 NOTE ON THE PHONOLOGY OF MIDDLE−ENGLISH...................................................................5 ABBREVIATIONS (LANGUAGES),..................................................................................................11 A CONCISE DICTIONARY OF MIDDLE−ENGLISH....................................................................................12 A.............................................................................................................................................................12 B.............................................................................................................................................................48 C.............................................................................................................................................................82 D...........................................................................................................................................................122 -

The Financial Crisis and Its Impact on the Electric Utility Industry

The Financial Crisis and Its Impact On the Electric Utility Industry Prepared by: Julie Cannell J.M. Cannell, Inc. Prepared for: Edison Electric Institute February 2009 © 2009 by the Edison Electric Institute (EEI). All rights reserved. Published 2009. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system or method, now known or hereinafter invented or adopted, without the express prior written permission of the Edison Electric Institute. Attribution Notice and Disclaimer This work was prepared by J.M. Cannell, Inc. for the Edison Electric Institute (EEI). When used as a reference, attribution to EEI is requested. EEI, any member of EEI, and any person acting on its behalf (a) does not make any warranty, express or implied, with respect to the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of the information, advice or recommendations contained in this work, and (b) does not assume and expressly disclaims any liability with respect to the use of, or for damages resulting from the use of any information, advice or recommendations contained in this work. The views and opinions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of EEI or any member of EEI. This material and its production, reproduction and distribution by EEI does not imply endorsement of the material. Published by: Edison Electric Institute 701 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20004-2696 Phone: 202-508-5000 Web site: www.eei.org The Financial Crisis and Its Impact on the Electric Utility Industry Julie Cannell Julie Cannell is president of J.M. -

Reading the Remains of the 17Th Century

AnthroNotes Volume 28 No. 1 Spring 2007 WRITTEN IN BONE READING THE REMAINS OF THE 17TH CENTURY by Kari Bruwelheide and Douglas Owsley ˜ ˜ ˜ [Editor’s Note: The Smithsonian’s Department of Anthro- who came to America, many willingly and others under pology has had a long history of involvement in forensic duress, whose anonymous lives helped shaped the course anthropology by assisting law enforcement agencies in the of our country. retrieval, evaluation, and analysis of human remains for As we commemorate the 400th anniversary of the identification purposes. This article describes how settlement of Jamestown, it is clear that historians and ar- Smithsonian physical anthropologists are applying this same chaeologists have made much progress in piecing together forensic analysis to historic cases, in particular seventeenth the literary records and artifactual evidence that remain from century remains found in Maryland and Virginia, which the early colonial period. Over the past two decades, his- will be the focus of an upcoming exhibition, Written in Bone: torical archaeology especially has had tremendous success Forensic Files of the 17th Century, scheduled to open at the in charting the development of early colonial settlements Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in No- through careful excavations that have recovered a wealth vember 2008. This exhibition will cover the basics of hu- of 17th century artifacts, materials once discarded or lost, man anatomy and forensic investigation, extending these and until recently buried beneath the soil (Kelso 2006). Such techniques to the remains of colonists teetering on the edge discoveries are informing us about daily life, activities, trade of survival at Jamestown, Virginia, and to the wealthy and relations here and abroad, architectural and defensive strat- well-established individuals of St. -

New Monarchs, Exploration & 16Th Century Society

AP European History: Unit 1.3 HistorySage.com New Monarchs, Exploration & 16th Century Society I. “New” Monarchs: c.1460-1550 Use space below for A. Consolidated power and created the foundation for notes Europe’s first modern nation-states in France, England and Spain. 1. This evolution had begun in the Middle Ages. a. New Monarchs on the continent began to make use of Roman Law and declared themselves “sovereign” while incorporating the will and welfare of their people into the person of the monarch This meant they had authority to make their own laws b. Meanwhile, monarchies had grown weaker in eastern Europe during the Middle Ages. 2. New Monarchies never achieved absolute power; absolutism did not emerge effectively until the 17th century (e.g. Louis XIV in France). 3. New Monarchies also were not nation-states (in the modern sense) since populations did not necessarily feel that they belonged to a “nation” a. Identity tended to be much more local or regional. b. The modern notion of nationalism did not emerge until the late 18th and early 19th centuries. B. Characteristics of New Monarchies 1. Reduced the power of the nobility through taxation, confiscation of lands (from uncooperative nobles), and the hiring of mercenary armies or the creation of standing armies a. The advent of gunpowder (that resulted in the production of muskets and cannon) increased the vulnerability of noble armies and their knights b. However, many nobles in return for their support of the king gained titles and offices and served in the royal court or as royal officials 2. -

Medieval Or Early Modern

Medieval or Early Modern Medieval or Early Modern The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton Medieval or Early Modern: The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Ronald Hutton and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7451-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7451-9 CONTENTS Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Ronald Hutton Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 10 From Medieval to Early Modern: The British Isles in Transition? Steven G. Ellis Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 29 The British Isles in Transition: A View from the Other Side Ronald Hutton Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 42 1492 Revisited Evan T. Jones Chapter Five ............................................................................................. -

The Rise of Commercial Empires England and the Netherlands in the Age of Mercantilism, 1650–1770

The Rise of Commercial Empires England and the Netherlands in the Age of Mercantilism, 1650–1770 David Ormrod Universityof Kent at Canterbury The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C David Ormrod 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Plantin 10/12 pt System LATEX2ε [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 521 81926 1 hardback Contents List of maps and illustrations page ix List of figures x List of tables xi Preface and acknowledgements xiii List of abbreviations xvi 1 National economies and the history of the market 1 Leading cities and their hinterlands 9 Cities, states and mercantilist policy 15 Part I England, Holland and the commercial revolution 2 Dutch trade hegemony and English competition, 1650–1700 31 Anglo-Dutch rivalry, national monopoly and deregulation 33 The 1690s: internal ‘free trade’ and external protection 43 3 English commercial expansion and the Dutch staplemarket, 1700–1770 -

Lasting Impressions: Conservation and the 2001 California Energy Crisis

Lasting Impressions: Conservation and the 2001 California Energy Crisis Loren Lutzenhiser, Portland State University Rick Kunkle, Washington State University James Woods and Susan Lutzenhiser, Portland State University Sylvia Bender, California Energy Commission ABSTRACT This paper presents the results of a study of household conservation response to the California energy supply crises during the summer of 2001 and in the post-crisis year of 2002. It draws upon two statewide telephone survey waves, with matched consumption information from customer electricity bills, and weather data from various parts of the state. The analysis explores conservation behavior, energy attitudes, social and housing demographics, and estimated energy savings. We found that the conservation response to the crisis exceeded expectations in the energy policy community, with consumers showing surprising flexibility in their energy demands, and for reasons other than energy prices. While conservation actions (both behavioral and hardware purchase) were reported by a large majority of households, they were also somewhat socially segmented, and the resulting energy savings were not evenly distributed across the population. There was persistence of conservation a year after the crisis, as well as continuing concern by consumers about energy-related issues. As a result of the crisis experience, the routine functioning of the energy system seems to have been "problematized" for many Californians. Some implications of these findings for future energy efficiency and renewable energy policies are considered. The Problem Beginning in the summer of 2000, California experienced serious energy supply problems, sharp increases in wholesale (and retail) electricity and natural gas prices, and isolated blackouts. In response to the rapidly worsening electricity situation in California in late 2000, a variety of efforts were undertaken to enhance supply, encourage rapid voluntary reductions in demand, and provide incentives for actions that would result in load reductions. -

Deformations in a 16Th-Century Ceiling of the Pinelo Palace in Seville (Spain)

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Digital Graphic Documentation and Architectural Heritage: Deformations in a 16th-Century Ceiling of the Pinelo Palace in Seville (Spain) Juan Francisco Reinoso-Gordo 1,* , Antonio Gámiz-Gordo 2 and Pedro Barrero-Ortega 3 1 Architectural and Engineering Graphic Expression, University of Granada, 18071 Granada, Spain 2 Architectural Graphic Expression, University of Seville, 41012 Seville, Spain; [email protected] 3 Graphic Expression in Building Engineering, University of Seville, 41012 Seville, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-958-249-485 Abstract: Suitable graphic documentation is essential to ascertain and conserve architectural heritage. For the first time, accurate digital images are provided of a 16th-century wooden ceiling, composed of geometric interlacing patterns, in the Pinelo Palace in Seville. Today, this ceiling suffers from significant deformation. Although there are many publications on the digital documentation of architectural heritage, no graphic studies on this type of deformed ceilings have been presented. This study starts by providing data on the palace history concerning the design of geometric interlacing patterns in carpentry according to the 1633 book by López de Arenas, and on the ceiling consolidation in the 20th century. Images were then obtained using two complementary procedures: from a 3D laser scanner, which offers metric data on deformations; and from photogrammetry, which facilitates Citation: Reinoso-Gordo, J.F.; the visualisation of details. In this way, this type of heritage is documented in an innovative graphic Gámiz-Gordo, A.; Barrero-Ortega, P. approach, which is essential for its conservation and/or restoration with scientific foundations and Digital Graphic Documentation and also to disseminate a reliable digital image of the most beautiful ceiling of this Renaissance palace in Architectural Heritage: Deformations southern Europe. -

Energy Crisis Briefing

Name Date Energy Crisis Briefing Read and annotate the passage below. Introduction In October of 1973, members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) banned the export of petroleum (oil) to the United States. At the same time, they also lowered overall oil production within their countries, causing a decrease of petroleum available on the world market. This embargo caused a major energy crisis in the United States, where the cost of gas rose drastically and gas shortages led to long lines and rationing across the country. The embargo was lifted in March of 1974. Though the embargo itself only lasted about 5 months, its effects are still felt today. The Energy Situation in the United States in 1973 The economic and energy situation in 1973 made the United States especially sensitive to the oil embargo. For a variety of reasons, including the decline or depletion of some oil fields and the unintended effects of government economic policies, domestic production of petroleum was decreasing. At the same time, demand for energy was increasing. The difference between that demand and the supply of domestic oil was being filled by importing oil from other countries. Between 1950 and 1973, the percentage of United States energy demand supplied by foreign oil increased from 8% to 19%. This situation meant that the United States oil industry could not increase supply to fill the void created when the embargo was instituted. The market response was an increase in price. Effects on the United States Population and Economy The oil embargo quadrupled the cost of a barrel of oil within a short period of time.