Rewilding Lite: Using Traditional Domestic Livestock to Achieve Rewilding Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing a Better Breeding Program

Pedigree Analysis and How Breeding Decisions Affect Genes Jerold S Bell DVM, Clinical Associate Professor of Genetics, Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine To some breeders, determining which traits will appear in may be phenotypically uniform, but will rarely breed true due the offspring of a mating is like rolling the dice - a to the mix of dissimilar genes. combination of luck and chance. For others, producing certain traits involves more skill than luck - the result of One reason to outbreed would be to bring in new traits that careful study and planning. As breeders, you must your breeding stock does not possess. While the parents may understand how matings manipulate genes within your be genetically dissimilar, you should choose a mate that breeding stock to produce the kinds of offspring you desire. corrects your breeding animal's faults but complements its good traits. It is not unusual to produce an excellent quality When evaluating your breeding program, remember that individual from an outbred litter. The abundance of genetic most traits you're seeking cannot be changed, fixed or variability can place all the right pieces in one individual. created in a single generation. The more information you Many top-winning show animals are outbred. Consequently, can obtain on how certain traits have been transmitted by however, they may have low inbreeding coefficients and may your animal's ancestors, the better you can prioritize your lack the ability to uniformly pass on their good traits to their breeding goals. Tens of thousands of genes interact to offspring. After an outbreeding, breeders may want to breed produce a single individual. -

OCHRANA DENNÍCH MOTÝLŮ V ČESKÉ REPUBLICE Analýza Stavu

OCHRANA DENNÍCH MOTÝL Ů V ČESKÉ REPUBLICE Analýza stavu a dlouhodobá strategie Pro Ministerstvo životního prost ředí ČR zpracovali: Martin Konvi čka, Ji ří Beneš, Zden ěk Fric Přírodov ědecká fakulta Jiho české university (katedra zoologie) & Entomologický ústav BC AV ČR (odd ělení ekologie a ochrany p řírody) V Českých Bud ějovicích, 2010 SOUHRN Fauna českých denních motýl ů je v žalostném stavu – ze 161 autochtonních druh ů jich p řes 10 % vyhynulo, polovina zbytku ohrožená nebo zranitelná, vrší se d ůkazy o klesající po četnosti hojných druh ů. Jde o celovropský trend, ochrana motýl ů není uspokojivá ani v zemích našich soused ů. Jako nejznám ější skupina hmyzu motýli indikují špatný stav p řírody a krajiny v ůbec, jejich ú činná aktivní ochrana zast řeší ochranu v ětšiny druhového bohatství terrestrických bezobratlých. Příčinou žalostného stavu je dalekosáhlá prom ěna krajiny v posledním století. Denní motýli prosperují v krajin ě poskytující r ůznorodou nabídku zdroj ů v těsné blízkosti. Jako pro převážn ě nelesní živo čichy je pro n ě ideální jemnozrnná dynamická mozaika nejr ůzn ější typ ů vegetace, udržovaná disturbancí a následnou sukcesí. Protože sou časé taxony jsou starší než geologické období čtvrtohor, v ětšina z nich se vyvinula v prost ředí ovliv ňovaném, krom ě i dnes p ůsobících ekologických činitel ů, pastevním tlakem velkých býložravc ů. Řada velkých evropských býložravc ů b ěhem mladších čtvrtohor vyhynula, zna čnou m ěrou p řisp ěním člov ěka. Člov ěk však nahradil jejich vliv svým hospoda řením udržoval v krajin ě, jež dlouho do 20. století udrželo jemnozrnnou dynamickou mozaiku, podmínku prosperity mnoha druh ů. -

Conservation Grazing.Pdf

MINNESOTA WETLAND RESTORATION GUIDE CONSERVATION GRAZING TECHNICAL GUIDANCE DOCUMENT Document No.: WRG 6A-5 Publication Date: 1/30/2014 Table of Contents Introduction Application Other Considerations Costs Additional References INTRODUCTION Grazing by bison, elk and deer was historically a natural occurrence in grassland and shrubland plant communities in Minnesota. This grazing tended to be nomadic in nature and its intensity depended on the type of grazers, herd sizes, climate conditions, fire frequency, and the composition and structure of individual plant communities. Today conservation grazing is conducted by a variety of species including cattle, bison, horses, sheep, and goats to target specific invasive plants, or to replicate the grassland plant community structure and diversity that historically resulted from grazing. When grazing is conducted to control invasive species the intensity and duration of grazing is carefully monitored to ensure that target species are managed effectively, and that the integrity of the plant community is maintained. Most conservation grazing involves a short pulse of grazing followed by a long rest. Grazing can have benefits as well as negative impacts, so it is important to involve experienced professionals. Detailed grazing plans are an important component in the planning and implementation of prescribed grazing. Equipment that may be needed for grazing includes watering systems, electric, or barb”ed” wire fences around rotational grazing areas, moveable fencing to concentrate grazing and to ensure that areas are not overgrazed, and in some cases salt licks to concentrate animals (Tu et al. 2001). The following is a list of species commonly used for conservation grazing and their general characteristics. -

Getting Her Bred Continued from Page 67

Advice for ensuring your females breed with ease. by Christy Couch Lee h, if only there was a magic wand to ensure Oa female — whether a first-calf heifer or a mature cow — would breed on the first try, every time. Alas, there is not. “Successful breeding is a combination of things done way ahead of breeding season, and things done at the moment of inseminating a female,” says Max Stotz, GKB Cattle, Waxahachie, Texas. “But there is no magic key. It’s simply a combination of many things that I’ve found over the years to be helpful in accomplishing the goal.” Through trial and error and decades in the business, Stotz; Marty Lueck, Journagan Ranch/ Missouri State University (MSU), Springfield, Mo.; and Kyle Gillooly, CES Polled Herefords, Wadley, Ga., say they’ve discovered what works for their operations and for their regions of the country. Stotz has been involved in the Hereford industry since childhood. After graduating from The Ohio State University, he began working for Ace Cattle Co., which became Star Lake Cattle Ranch. Last year, he began managing the cow herd at GKB. For 32 years, Lueck has overseen Journagan’s 3,300 acres and 480 purebred and 150 commercial cows Getting with four employees. Each year, the operation hosts an annual sale and markets up to 100 bulls through the sale and private treaty. Gillooly was raised in the Hereford and Angus business in Indiana. He met his wife, Jennifer, while showing Herefords, and when they were married in 2006, he began managing her grandfather’s Her Bred cattle operation. -

Management of Grazing Animals for Environmental Quality

Management of grazing animals for environmental quality Etienne M. in Molina Alcaide E. (ed.), Ben Salem H. (ed.), Biala K. (ed.), Morand-Fehr P. (ed.). Sustainable grazing, nutritional utilization and quality of sheep and goat products Zaragoza : CIHEAM Options Méditerranéennes : Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; n. 67 2005 pages 225-235 Article available on line / Article disponible en ligne à l’adresse : -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ http://om.ciheam.org/article.php?IDPDF=6600046 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ To cite this article / Pour citer cet article -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ Etienne M. Management of grazing animals for environmental quality. In : Molina Alcaide E. (ed.), Ben Salem H. (ed.), Biala K. (ed.), Morand-Fehr P. (ed.). Sustainable grazing, nutritional utilization and quality of sheep and goat products . Zaragoza : CIHEAM, 2005. p. 225-235 (Options Méditerranéennes : Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; n. 67) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------ http://www.ciheam.org/ -

Upper Mustang Biodiversity Conservation Project Final Report

UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Upper Mustang Biodiversity Conservation Project ATLAS ID GEF-00013971 TRAC-00013970 (formerly NEP/99/G35 and NEP/99/021) Final Report of the Terminal Evaluation Mission September 2006 Phillip Edwards (Team Leader) Rajendra Suwal Neeta Thapa ACRONYMS AND TERMS Exchange rate at the time of the TPE was US$1 to NR 71 (Nepali Rupees) ACA Anapurna Conservation Area ACAP Anapurna Conservation Area Project AHF American Himalayan Foundation APPA Appreciative Participatory Planning and Action BCP Biodiversity Conservation Plan CAMC Conservation Area Management Committee CAMOP Conservation Area Management Operation Plan CAMP Conservation Area Management Plan CAMR Conservation Area Management Regulation CBBMS Community Based Biodiversity Monitoring System CBO Community Based Organization CITES Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species CPM Co-Project Manager CRAC Community Resource Action Area Committee CRAJSC Community Resources Action Joint Sub-Committee CTF Community Trust Fund DAG Disadvantage Group DDC District Development Committee DNPWC Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation EIA Environment Impact Assessment FIT Free Independent Tourist/Trekker GEF Global Environment Facility GIS Geographic Information System GON Government of Nepal Ha. Hectares HMG His Majesty’s Government HQ Head Quarters HRD Human Resource Development ICDP Integrated Conservation Development Program ICIMOD International Center for Integrated Mountain Development IEA Initial Environmental Assessment IGA Income -

How to Manage Different Habitats Commons Factsheet No

How to manage different habitats Commons Factsheet No. 08 www.naturalengland.co.uk How to manage different habitats Many commons and greens are beautiful places, rich in wildlife. Because commons have a long history of being used by people, the habitats they support are relatively natural but have been shaped by human activities over the millennia (e.g. unimproved grassland, heathland, woodlands). If they are to retain their wildlife and scenery the traditional uses must either be continued, or replicated some other way (see FS3 Why does our common need to be looked after?). This factsheet summarises the characteristic features of each habitat type, together with conservation aims and management techniques for habitats frequently found on commons. Different techniques Before deciding on particular management techniques, you will want to consider their The management of habitats can vary from potential impact on the species present, simple to complex. It can often be carried the landscape, the environment, features out by volunteers with hand tools or may of archaeological and historical interest, need people with specialised training and and public access and safety (see FS5 Is our equipment. Here, the main methods you common more special than we think?, FS4 Who might use are outlined and sources of further has an interest in the common? and FS8 What information signposted. Herbicide treatments future for our commons?). Remember to plan are not discussed, as these are best used only aftercare and monitoring (see FS17 Are we if there are no other realistic options, and getting it right?). you will want specialist advice and possibly contractors to carry out the work. -

How Science Supports Fiction, Or to Which Extent Technologies Have Advanced the Progress Towards the Vision of De – Extinction

How science supports fiction, or to which extent technologies have advanced the progress towards the vision of de – extinction Iwona Kowalczyk Students’ Scientific Association of Cancer Genetics Department of Cancer Genetics Laboratory for Cytogenetics I Faculty of Medicine with Dentistry Division Medical University of Lublin, Radziwiłłowska Street 11, 20-080 Lublin, Poland [email protected] Supervisor of the paper: dr hab. of medical sciences Agata Filip De – extinction, or the attempt of trying to bring back to the world different animal species which are already gone extinct, is lately gaining more and more acclaim, among others due to the fact, that emerging technologies of genetic engineering are opening a wide range of new possibilities in the field. Starting from the techniques which make the isolation of ancient DNA more effective, through the methods of its amplification and sequencing, to finally discovering the whole genomes, the plan of making de – extinction real is becoming gradually more possible. Successful sequencing of the mitochondrial genome of extinct quagga was a breakthrough, then the time for other species came. Great hopes are placed on restriction enzymes, especially those which work in CRISPR/Cas9 system, which enable us to edit the genomes of living relatives still more efficiently. Apart from genome editing, the methods of selective back - breeding or cell nuclear transfer are used. Each species requires an individual consideration in the terms of the DNA material available, choosing the optimal method and the likelihood of successful de – extinction. The idea, however, leaves still many questions unanswered on the aspects such as ethics, ecology, funds and society, therefore it is doubtful, if we are ever going to face the full restoration of population once gone extinct. -

Výroční Zpráva

2017 VÝROČNÍ ZPRÁVA Zoologická a botanická zahrada města Plzně / VÝROČNÍ ZPRÁVA 2017 Zoologická a botanická zahrada města Plzně Zoological and Botanical Garden Pilsen/ Annual Report 2017 Provozovatel ZOOLOGICKÁ A BOTANICKÁ ZAHRADA MĚSTA PLZNĚ, příspěvková organizace ZOOLOGICKÁ A BOTANICKÁ ZAHRADA MĚSTA PLZNĚ POD VINICEMI 9, 301 00 PLZEŇ, CZECH REPUBLIC tel.: 00420/378 038 325, fax: 00420/378 038 302 e-mail: [email protected], www.zooplzen.cz Vedení zoo Management Ředitel Ing. Jiří Trávníček Director Ekonom Jiřina Zábranská Economist Provozní náměstek Ing. Radek Martinec Assistent director Vedoucí zoo. oddělení Bc. Tomáš Jirásek Head zoologist Zootechnik Svatopluk Jeřáb Zootechnicist Zoolog Ing. Lenka Václavová Curator of monkeys, carnivores Jan Konáš Curator of reptiles Miroslava Palacká Curator of ungulates Botanický náměstek, zoolog Ing. Tomáš Peš Head botanist, curator of birds, small mammals Botanik Mgr. Václava Pešková Botanist Propagace, PR Mgr. Martin Vobruba Education and PR Sekretariát Alena Voráčková Secretary Privátní veterinář MVDr. Jan Pokorný Veterinary Celkový počet zaměstnanců Total Employees (k 31. 12. 2017) 130 Zřizovatel Plzeň, statutární město, náměstí Republiky 1, Plzeň IČO: 075 370 tel.: 00420/378 031 111 Fotografie: Kateřina Misíková, Jiří Trávníček, Tomáš Peš, Miroslav Volf, Martin Vobruba, Jiřina Pešová, archiv Zoo a BZ, DinoPark, Oživená prehistorie a autoři článků Redakce výroční zprávy: Jiří Trávníček, Martin Vobruba, Tomáš Peš, Alena Voráčková, Kateřina Misíková, Pavel Toman, David Nováček a autoři příspěvků 1 výroční -

Governing with Nature: a European Perspective on Putting Rewilding Rstb.Royalsocietypublishing.Org Principles Into Practice

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on October 24, 2018 Governing with nature: a European perspective on putting rewilding rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org principles into practice P. Jepson1, F. Schepers2 and W. Helmer2 1School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QY, UK Research 2Rewilding Europe, 6525 Nijmegen, The Netherlands Cite this article: Jepson P, Schepers F, PJ, 0000-0003-1419-9981 Helmer W. 2018 Governing with nature: a European perspective on putting rewilding Academic interest in rewilding is moving from commentary to discussion on future research agendas. The quality of rewilding research design will be principles into practice. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B enhanced if it is informed by knowledge of the rewilding practice. Here, 373: 20170434. we describe the conceptual origins and six case study examples of a mode http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0434 of rewilding that emerged in the Dutch Delta and is being promoted and supported by Rewilding Europe, an umbrella organization established in Accepted: 11 August 2018 2011. The case experiences presented help position this version of rewilding in relation to the US 3C’s version and point towards a rewilding action philosophy characterized by pragmatic realism and pioneer projects One contribution of 16 to a theme issue around which multiactor networks interested in policy innovation and ‘Trophic rewilding: consequences for change form. We argue that scaling-up the models of rewilding presented ecosystems under -

Aurochs Genetics, a Cornerstone of European Biodiversity

Aurochs genetics, a cornerstone of European biodiversity Picture: Manolo Uno (c) Staffan Widstrand Authors: • drs. Ronald Goderie (Taurus Foundation); • dr. Johannes A. Lenstra (Utrecht University, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine); • Maulik Upadhyay (pHD Wageningen University); • dr. Richard Crooijmans (Animal Breeding and Genomics Centre, Wageningen University); • ir. Leo Linnartz (Ark Nature) Summary of: Aurochs Genetics, a cornerstone of biodiversity Preface In 2015 a report is written on Aurochs genetics, made possible by a grant from the Dutch Liberty Wildlife fund. This fund provided the Taurus foundation with a grant of EUR 20.000 to conduct genetic research on aurochs and its relation with nowadays so- called ‘primitive’ breeds. This is the summary of that report. This summary shortly describes the current state of affairs, what we do know early 2015 about the aurochs, about domestic cattle and the relationship of aurochs and the primitive breeds used in the Tauros Programme. Nijmegen, December 2015. page 2 Summary of: Aurochs Genetics, a cornerstone of biodiversity Table of contents Preface 2 Table of contents ......................................................................................................... 3 Summary ..................................................................................................................... 4 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 6 2 Aurochs: a short description ................................................................................. -

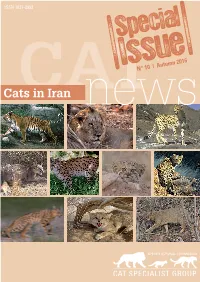

Tiger in Iran

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 10 | Autumn 2016 CatsCAT in Iran news 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Cover Photo: From top left to bottom right: Caspian tiger (K. Rudloff) This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Asiatic lion (P. Meier) from the Wild Cat Club and Zoo Leipzig. Asiatic cheetah (ICS/DoE/CACP/ Panthera) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh caracal (M. Eslami Dehkordi) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Tabea Lanz Eurasian lynx (F. Heidari) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Pallas’s cat (F. Esfandiari) Persian leopard (S. B. Mousavi) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Asiatic wildcat (S. B. Mousavi) sand cat (M. R. Besmeli) jungle cat (B. Farahanchi) The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.