The Vulnerability of Urban Elementary School Arts Programs : a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KARLIN J. TICHENOR, Phd, LLMFT Home Address Office Address

Tichenor CV 1 of 17 KARLIN J. TICHENOR, PhD, LLMFT (317) 372-4688 [email protected] [email protected] Home Address Office Address 5911 Draycott Drive 603 E. Washington Street, Suite #800 Indianapolis, Indiana 46236 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy, Human Development and Family Studies (January 2012 – May 2016) Specialization in Couple and Family Therapy East Lansing, Michigan Michigan State University Master of Arts, Marriage and Family Therapy (MFT) (January 2010 - December 2011) Human Development and Family Studies, Marriage and Family Therapy East Lansing, Michigan Michigan State University Bachelor of Arts (August 2005 – May 2009) Major: Communication; Minor: Psychology Granville, Ohio Department of Communication Denison University PROFESSIONAL LICENSES Approved Supervisor License Pending American Association of Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT) Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist Pending State of Indiana, Board of Marriage and Family March 2011 License # Limited Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist State of Michigan, Board of Marriage and Family License #4101006530 GRANTS & FELLOWSHIPS Leadership Lansing Program September 2018-May 2019 $2,000 Lansing Regional Chamber Michigan Education Policy Fellowship Program (EPFP) June 2015-May 2016 $2,700 Education Policy Center at Michigan State University Institute for Educational Leadership Sponsored by the Lansing School District King-Chavez-Parks (KCP) Future Faculty Fellowship Program April 2015-April 2016 $35,000 KCP Future Faculty Fellow Tichenor -

Journal of the Senate 95Th Legislature REGULAR SESSION of 2009

No. 60 STATE OF MICHIGAN Journal of the Senate 95th Legislature REGULAR SESSION OF 2009 Senate Chamber, Lansing, Wednesday, July 15, 2009. 10:00 a.m. The Senate was called to order by the President pro tempore, Senator Randy Richardville The roll was called by the Secretary of the Senate, who announced that a quorum was present. Allen—present Garcia—present Olshove—present Anderson—present George—present Pappageorge—present Barcia—present Gilbert—present Patterson—present Basham—present Gleason—present Prusi—present Birkholz—present Hardiman—present Richardville—present Bishop—present Hunter—present Sanborn—present Brater—excused Jacobs—present Scott—present Brown—present Jansen—present Stamas—present Cassis—present Jelinek—present Switalski—present Cherry—present Kahn—present Thomas—present Clark-Coleman—present Kuipers—present Van Woerkom—present Clarke—present McManus—present Whitmer—present Cropsey—present 1202 JOURNAL OF THE SENATE [July 15, 2009] [No. 60 Senator Gerald Van Woerkom of the 34th District offered the following invocation: Heavenly Father, we come to You to offer praise and honor to Your name. We are grateful that You are our God, we are grateful that You watch over us, and we are grateful that You bless us. We pray that You will continue to look upon us with Your favor. We pray that You will grant us wisdom as we make decision here in this body today. We pray that You will give us a sense of vision for what we ought to do for the people of our state. We are making some very difficult choices over the next couple of weeks and, Lord, we pray that You will help us to put forth good priorities so that people who need special care within our state might be provided for. -

2018 Things to Do at MSU (PDF)

Blank Page WorkLife Office THINGS TO DO AT MSU An Activity Guide for Families Brought to you by: MSU WorkLife Office 2018 Edition 479 West Circle Drive Linton Hall http://worklife.msu.edu Suites 116/118 [email protected] East Lansing, MI 48824 (517) 353-1635 About the MSU WorkLife Office The MSU WorkLife Office provides a one-stop destination for faculty and staff lifespan and career/professional life questions and information. This activity guide assists all families in exploring their community and helps them become acquainted with this rich environment. Whether you are an MSU faculty or staff member, student, or a community member, you will find activity information for people of all ages on campus and in the Greater Lansing area. For more information about MSU WorkLife Office services: Phone: (517) 353-1635 Email: [email protected] Web: http://worklife.msu.edu WorkLife Office Last updated: April 2018 Booklet designed by Burning Daylight Design, LLC INSIDE THIS GUIDE 3-4 ...........Activity Resources / Maps / Parking 5-6 ...........Art & Music 7 ................School of Music Camps 8-10 ........Academics for Children 11 ...............Museums 12-14 ......Animals & Gardens 15-16 ......Campus Attractions 17-20 .....Sports & Activities 21-26 .....Off-Campus Activities & Attractions 27-32 .....Calendar (On/Off-Campus Events) 33 .............Miscellaneous 34 .............MSU Federal Credit Union ACTIVITY RESOURCES Things to do at MSU Spartan Youth An Activity Guide Programs for Families www.spartanyouth.msu.edu The website provides parents, http://worklife.msu.edu This activity guide is also youth, and educators with an easy available online on the WorkLife way to access information about Office website. -

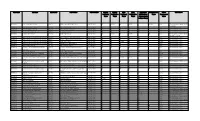

Middle School Target Improvement Target Target Target Target Other Academic Status Indicator Target

State Name LEA Name LEA NCES ID School Name School NCES ID Reading Reading Math Math Elementary/ Graduation Rate School Title I School Proficiency Participation Proficiency Participation Middle School Target Improvement Target Target Target Target Other Academic Status Indicator Target MICHIGAN Battle Creek Public Schools 2600005 Battle Creek Central High School 260000503830 All Not All All Not All Not All Focus Title I schoolwide eligible school- No program MICHIGAN Battle Creek Public Schools 2600005 Valley View Elementary School 260000503847 All All All All All Focus Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Battle Creek Public Schools 2600005 Verona Elementary School 260000503848 Not All All All All All Priority Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Bessemer Area School District 2600006 Washington School 260000603855 All All All All All Focus Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN St. Ignace Area Schools 2600012 LaSalle High School 260001203862 All Not All All Not All All Focus Title I targeted assistance eligible school-No program MICHIGAN Wayne-Westland Community School District 2600015 Albert Schweitzer Elementary School 260001503880 All All All All All Focus Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Wayne-Westland Community School District 2600015 Alexander Hamilton Elementary School 260001503881 All All All All All Priority Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Wayne-Westland Community School District 2600015 David Hicks School 260001503885 Not All All Not All All All Priority Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Wayne-Westland Community School District 2600015 Adlai Stevenson Middle School 260001503905 All All All All All Focus Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Bad Axe Public Schools 2600017 Bad Axe Middle School 260001703919 All All All All All Focus Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Joseph K. -

5-Year Parks & Recreation Master Plan 2017-2021

Charter Township of Meridian Department of Parks and Recreation Creating Community through People, Parks, and Programs 5-Year Parks & Recreation Master Plan 2017-2021 Adopted February 2017 Meridian Township Parks and Recreation Master Plan 1 Park Commission 2017-2021 Michael McDonald, Acting Chair Mark Stephens, Commissioner Richard Baker, Commissioner Amanda Lick, Commissioner Annika Brixie Schaetzl, Commissioner Parks and Recreation Staff LuAnn Maisner, Parks & Recreation Director Robin Faust, Administrative Assistant II Jane Greenway, Senior Parks and Land Management Coordinator Mike Devlin, Parks & Recreation Specialist Darcie Weigand, Parks & Recreation Specialist Kit Rich, Senior Park Naturalist, Harris Nature Center Kati Adams, Senior Park Naturalist, Harris Nature Center Kelsey Dillon, Stewardship Coordinator Dennis Antone, Facilities Superintendent Cheri Wisdom, Senior Center Coordinator Department of Parks and Recreation Meridian Township Parks and Recreation Master Plan 2 Table of Contents Page Introduction 8 I . Community Description 16 A. Location Description and Population Information 16 Map A: Location Map 18 B. Meridian Township Residents 19 C. Summary of The National Citizen Survey 2015 19 D. Township Millages & Ordinances 19 II. Administrative Structure 21 A. Role of the Township Board 21 B. Role of Park Commission 21 C. Role of Land Preservation Advisory Board 21 D. Role of Parks and Recreation Department 22 E. Parks and Recreation Administrative Staff 23 F. Organizational Chart 28 G. Funding Sources and Budget 29 H. Role of Volunteers 31 I. Relationships with School Districts, Other Public Agencies and Private Organizations 34 J. Role of the Environmental Commission 35 K. Other Environmental Planning Organizations 35 L. Communications 35 III. Parks and Recreation Inventory and Evaluation 37 A. -

The Naturalized Playground at Wexford Academy, Lansing

PLACE-BASED STEWARDSHIP EDUCATION CASE STUDIES The Naturalized Playground at Wexford Montessori Academy Lansing, Michigan An urban K-8 school About the case study This case study of place-based and partner with community-based The Naturalized Playground at stewardship education (PBSE) at organizations, and provide funding Wexford Academy Wexford Academy is one of 11 and other PBSE supports with an case studies developed by staff of environmental stewardship December 2017 the Great Lakes Stewardship emphasis. Wexford Montessori Initiative (GLSI), staff of the GLSI’s Magnet School has a longstanding Authors: nine regional hubs, and the relationship with its hub, the Kristan Small educators whose work is featured GRAND Learning Network. Shari Dann in the study. Margaret Holtschlag . Mark Stephens This case study focuses on a PBSE Lisa Marckini-Polk effort that began in 2013 and Rebecca Nielsen continued through the 2015–16 school year. At most of the sites Photographs: featured in these studies, Kristan Small including Wexford, the PBSE Dustin J Grimes approach has been developed Shari Dann over the course of several years. Margaret Holtschlag Mark Stephens Each school featured in a case study works with the GLSI through a regional hub. Hubs provide Supported by: professional development for U.S. Environmental Protection Agency educators, help schools connect (U.S. EPA) grant #00E01327 The Great Lakes Fishery Trust Cover: A rainbow shines over the playground at Wexford Montessori Academy. | 2 Contents Quick Summary Pages 5–6 A one-page overview -

Survey of MSU Graduates of Five Student Teaching Programs

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 166 163 SP 013 787 AUTHOR Freeman, Donald J.; And Others TITLE Survey of M.S.U. Graduates of Five Student Teaching Programs: Trends and Long-Range Outcomes of Student Teaching Programs Suggested by a Survey of Michigan State University Graduates and Their Supervisors. INSTITUTION Michigan State Univ., East Lansing. Coll. cf Education. PUB DATE Jan 79 NOTE 142p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$7.35 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Beginning Teachers; College Graduates; *College Supervisors; *Comparative Analysis; Followup Studies; *Graduate Surveys; Preservice Education; *Program Effectiveness; Questionnaires; Statistical Analysis; Student Teaching; *Teacher Employment; *Teacher Programs ABSTF ACT This report summarizes responses to an 84-item survey completed by 536 of 994 randomly selected graduates of Michigan State University. The sample includes graduates of five teacher preparation programs (regular, cluster, and overseas student teaching, elementary intern, and competency-based four enrollment periods. The report also reviews respOnses to a 43-item questionnaire completed by 236 of the 269 supervisors identified by active teachers in the sample. The most significant findings include:(1) There has been a slight decline in the percent of graduates who secure teaching positions;' (2) There has ileen a dramatic increase in t:Ie number who enter the profession as substitutes, paraprofessionals, or part-time teachers;(3) There are no significant differences among programs on any of the five subscales embedded within the surveys -- -

City and Schools Vision Advisory Committee: Rev

CHANGE FOR LANSING’S FUTURE State Rep and Mayoral Candidate Andy Schor City and Schools Vision Advisory Committee: Rev. Dr. Melvin T Jones Hon. Dr. Nino Rodriguez Hon. Gabrielle Johnson Hon. Melissa Lilje Professor Nancy Wonch Dr. Yvonne Camaal Canul This Advisory Committee includes individuals involved with our schools in Lansing. It also includes those doing work with our children and residents to help increase resources and tools for education. Many others not listed also provided feedback and input. This vision will continue to evolve throughout the campaign. P r o a c t i v e P l a t f o r m: A n d y S c h o r City and Schools I am the proud parent of two children in the Lansing School District. As mayor, I look forward to promoting the innovation and progress being made in our public schools. We need to prioritize familiarizing those with young children-- and those about to have children-- with the unique offerings our district has to offer, emphasizing Lansing as a district to choose. I will formalize a relationship between the Mayor’s office and the Lansing School District aimed at better showcasing and promoting the important improvements that we have made (and will continue to make). Moving forward, I would also like to see the City of Lansing partner with Ingham County, private partners, and the LSD to offer important wraparound services in our schools to help more directly address our community’s human service and socioeconomic needs. Additionally, I am committed to developing relationships with all of our schools (traditional public, private, and charter) as well as our higher education institutions in service of our community’s children. -

Ring, Ring Goes the Bell

FREE Locally owned Aug. 26 - Sept. 1, 2020 www.lansingcitypulse.com A newspaper for the rest of us Ring, ring goes the bell Mid-Michigan schools ‘reopen’ SEE PAGE 12 -NEVIN ‘20 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • August 26, 2020 CLEANING YOUR HOUSE? Don't forget your drains! $ Schedule drain cleaning on YOUR schedule to keep 30 OFF them flowing BEFORE they stop entirely ANY SERVICE We offer full range of cabling and water jetting of lines CALL OVER Camera inspection/location services $100 COUPON EXPIRES 9/30/2020 CODE: CP2020 10% OFF ANY DRAIN CLEANING OR CAMERA INSPECTION MAXIMUM DISCOUNT $50 CODE: CP2020 COUPON EXPIRES 9/30/2020 We are a 3rd generation family owned business serving Greater Lansing since 1939 CALL 1-800-HEDLUND OR 517-321-5955 SPECIALIZING IN SAME DAY SERVICE City Pulse • August 26, 2020 www.lansingcitypulse.com 3 TWO GREAT LOCAL LEGENDS HAVE FINALLY COME TOGETHER! NOW YOU CAN PICK UP CITY PULSE IN ALL GREATER LANSING QDs!* FREE 12 oz. QD Gourmet Coffee Redeemable at All 28 QD Locations. Coupon Expires 9/1/2020. PLU# 41 * City Pulse available at all QD Stores Except Charlotte, Eaton Rapids and Fowler. 4 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • August 26, 2020 VOL. 20 ISSUE 3 (517) 371-5600 • Fax: (517) 999-6061 • 1905 E. Michigan Ave. • Lansing, MI 48912 • www.lansingcitypulse.com ADVERTISING INQUIRIES: (517) 999-5061 or email [email protected] PAGE CLASSIFIEDS: (517) 999-6704 EDITOR AND PUBLISHER • Berl Schwartz 7 [email protected] • (517) 999-5061 ARTS & CULTURE EDITOR • Skyler Ashley Catch -

Educator Workforce Data Report 2021

OFFICE OF Educator Excellence Educator WORKFORCE Data Report 2021 We encourage the distribution and use of metrics presented within this report. If you choose to utilize any metric from this document we ask that you include the following note: “Source: 2021 Office of Educator Excellence (OEE) Educator Workforce Data Report http://bit.ly/2020-21Report” Educator Workforce Data Report | July 1, 2019 - June 30, 2020* *Data reporting window, unless otherwise indicated. Dr. Casandra E. Ulbrich Dr. Judith Pritchett The Honorable Gretchen Whitmer President NASBE Delegate Governor Dr. Pamela Pugh Ms. Ellen Cogen Lipton ex officio Vice President Ms. Nikki Snyder Dr. Michael F. Rice Chairman, ex officio Ms. Tiffany Tilley Mr. Jason Strayhorn Secretary State Superintendent Mr. Tom McMillin Mrs. Marilyn Schneider Treasurer State Board Executive Key to this work is leveraging the rich data sources available through the Michigan Department of Education (MDE) and the Center for Educational Performance and Information (CEPI) – including the Michigan Online Educator Certification System (MOECS) and Registry of Educational Personnel (REP). Additional educator workforce resources are available: Title II Teacher Preparation Data | MDE Educator Workforce Research and White Papers | MI School Data/CEPI (https://bit.ly/3ekjGtK) (http://bit.ly/33deIJ3) (http://mischooldata.org) NOTE: In some cases, data may be rounded, resulting in a sum slightly greater or less than 100%. Throughout the report, for certificates without an expiration date, those issued prior to January 1, 1980 were excluded. FROM THE DIRECTOR’S DESK Dear Michigan Education Stakeholder, On behalf of the Michigan Department of Education (MDE) Office of Educator Excellence (OEE), it is my pleasure to present to you this year’s Educator Workforce Data Report. -

1 PROJECT MANUAL Lansing School District Projects: Everett H. S

Lansing School District Lansing Bid : SO#1320 Everett, Eastern and Sexton H. S. PC Project No. 0106 Science, Computer and Media GMB Architects/Engineering Pleasantview Magnet -Café/Classroom Purchasing Concepts, Inc Lansing, Michigan 48933 Holland, Michigan 49423 PROJECT MANUAL Lansing School District Projects: Everett H. S. – GMB-5307 Eastern H. S. – GMB-5306 Sexton H. S. - GMB-5309 Pleasantview- GMB-5301 Furniture and Furnishings Science, Computer, and Media Remodeling Cafetorium and Classroom LSD Project- SO# 1320 GMB Architects & Engineering 85 E. Eighth St. Holland, MI 49423 (616) 796 0200 Purchasing Concepts, Inc. 5641 Sugarberry Dr Kentwood, MI 49512 (616) 871- 9645 1 Lansing School District Lansing Bid : SO#1320 Everett, Eastern and Sexton H. S. PC Project No. 0106 Science, Computer and Media GMB Architects/Engineering Pleasantview Magnet -Café/Classroom Purchasing Concepts, Inc Lansing, Michigan 48933 Holland, Michigan 49423 SECTION 00003 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION TITLE PAGES BIDDING REQUIREMENTS, CONTRACT FORMS AND CONDITIONS OF THE CONTRACT 00001 Title Page …………………………………………………… Page 1 00003 Table of Contents …………………………………………… Page 2 00030 Advertisement for Bids ……………………………………... Page 3-4 00100 Instructions to Bidders ………………………………………. Page 5-10 00300 Bid Form …………………………………………………….. Page 11- 30 00400 Supplement to Bid Form -------- Vendor Application Page 31-33 ------- Familial Relationship Affidavit Page 34 00800 Supplementary Conditions -------- Purchasing Policy Page 35 ------- Insurance Requirements Page 36-37 SPECIFICATIONS -

In This Issue

THE MONTHLY BUSINESS NEWS MAGAZINE OF THE LANSING REGIONAL CHAMBER OF COMMERCE • JULY 2021 IN THIS ISSUE LRCC ANNOUNCES DEI COMMITMENT VOICE OF SMALL BUSINESS RECOGNIZES THE POWER OF TEAMWORK A SWEET ENCOUNTER THAT IS BUILT TO LAST MESSAGE FROM THE CHAMBER 2020: A Year Unlike Any Other s the Lansing Regional Chamber of Commerce (LRCC) team worked to produce our 2020 Annual Report, I was struck by the Arealization of how many dedicated people and organizations in this region stayed true to their mission. They even thrived during the most challenging year many of us has ever experienced, which has also been true for our LRCC team. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the LRCC was steadfast in providing our region’s employers with meaningful, timely content and proactively turning challenges into innovation and resiliency while delivering leadership and value to the Lansing region. In 2020, the LRCC understood that local businesses were faced with so much uncertainty and forced to navigate an unknown landscape that presented many economic challenges. For that reason, LRCC was committed to finding ways to stay connected and support each other while physically apart. The results of our intensified efforts to communicate and connect with members were well received. In 2020, LRCC experienced TIM DAMAN 65% member engagement levels and 91% member retention, despite the challenges that demanded so much of our member’s President and CEO attention during the year. Lansing Regional Chamber of Commerce As the voice of business in Greater Lansing, the LRCC recognized that our role in providing regional leadership was never more important than during the challenging times we have dealt with the past several months.