Commoning and Learning from Athens, Documenta 14 (2017) Performative Occupations, Instituting and Infrastructures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

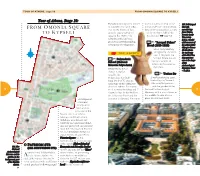

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

Athens, Greece

NOVEMBER 2014 | PRICE €400 IN FOCUS: ATHENS, GREECE Pavlos Papadimitriou, MBA Senior Associate Panagiotis Verykios Analyst www.hvs.com HVS ATHENS | 17 Posidonos Ave. 5th Floor, 17455 Alimos, Athens, GREECE This market snapshot is part of a series of articles that HVS occasionally produces on key tourism destinations across Greece. In writing these articles, we utilise the expertise of HVS for each market to the full extent combining our in- house data and research together with published information regarding each of the examined destinations. Highlights • Since 2009 the negative publicity stemming from the rumours regarding the economic situation of Greece led to socio- political and economic turbulence which generated significant fluctuations in tourist arrivals during the period of 2009- 12. Due to the double elections held in May and June of that year, 2012 was rather ‘slow’ for Greek tourism. Tourism statistics for Athens over the period 2009-11 were also volatile, contrary to resort destinations which have followed a rather stable or upward path in the last few years. Moreover, approximately 80 hotels closed down in the same period, the vast majority of them classified as three-star and lower; • During 2008-12, revenue per available room (RevPAR) for all hotels in Athens decreased by a remarkable 35.9% as a result of the economic crisis that affected the city. For the same period, RevPAR for five-star hotels decreased by 30.5% and for four-star hotels by 36.4%; • According to one of the most recent reports of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Greece has unquestionably made significant strides in overcoming deep-rooted problems, with the three most noteworthy achievements standing out being the progress on fiscal adjustment, the narrowing of the competitiveness gap, and the stabilisation of the banking sector; • In 2013, 17.9 million international tourists visited Greece, spending €12.0 billion, up from €10.4 billion in 2012. -

Athens Strikes & Protests Survival Guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the Crisis Day Trip Delphi, the Navel of the World Ski Around Athens Yes You Can!

Hotels Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Events Maps ATHENS Strikes & Protests Survival guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the crisis Day trip Delphi, the Navel of the world Ski around Athens Yes you can! N°21 - €2 inyourpocket.com CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES Contents The Basics Facts, habits, attitudes 6 History A few thousand years in two pages 10 Districts of Athens Be seen in the right places 12 Budget Athens What crisis? 14 Strikes & Protests A survival guide 15 Day trip Antique shop Spend a day at the Navel of the world 16 Dining & Nightlife Ski time Restaurants Best resorts around Athens 17 How to avoid eating like a ‘tourist’ 23 Cafés Where to stay Join the ‘frappé’ nation 28 5* or hostels, the best is here for you 18 Nightlife One of the main reasons you’re here! 30 Gay Athens 34 Sightseeing Monuments and Archaeological Sites 36 Acropolis Museum 40 Museums 42 Historic Buildings 46 Getting Around Airplanes, boats and trains 49 Shopping 53 Directory 56 Maps & Index Metro map 59 City map 60 Index 66 A pleasant but rare Athenian view athens.inyourpocket.com Winter 2011 - 2012 4 FOREWORD ARRIVING IN ATHENS he financial avalanche that started two years ago Tfrom Greece and has now spread all over Europe, Europe In Your Pocket has left the country and its citizens on their knees. The population has already gone through the stages of denial and anger and is slowly coming to terms with the idea that their life is never going to be the same again. -

Chlimintza, Elpida-Melpomeni (2010) Communication Processes in the Hellenic Fire Corps: a Comparative Perspective

Chlimintza, Elpida-Melpomeni (2010) Communication processes in the Hellenic fire corps: a comparative perspective. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1754/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the Author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Communication Processes in the Hellenic Fire Corps: A Comparative Perspective Elpida-Melpomeni Chlimintza Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Applied Social Sciences Faculty of Law, Business and Social Sciences University of Glasgow SEPTEMBER 2009 Photo: Grammattiko fire, 22/08/09 Communication Processes in the Hellenic Fire Corps: A Comparative Perspective Elpida-Melpomeni Chlimintza Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Applied Social Sciences Faculty of Law, Business and Social Sciences University of Glasgow SEPTEMBER 2009 ABSTRACT My research explores critical issues involved in emergency management in a front-line, emergency service – the fire brigade – in Greece, Germany and Britain. It is designed to identify the problems in the communication conduct among fire-fighters during emergency responses, to examine the causes of these problems and to suggest ways to overcome them that should allow European countries to adopt more effective policies. -

Master Thesis (Cohort: September 2017)

Institute of Security and Global Affairs Leiden University – Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs MSc in Crisis & Security Management Master Thesis (Cohort: September 2017) Vasileios Papageorgiou (s2090112) Supervisor: Drs. Tim Dekkers Second Reader: Dr. G.M. van Buuren Master Thesis Social Disorder in the City of Athens During the Economic Crisis Wordcount: 21720 10/06/18 Acknowledgements Many people contributed, one way or another, for the completion of this thesis. First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Drs. Dekkers, for his guidance and his valuable suggestions during all this time. I would also like to thank Dr. Elke Devroe, for introducing me into the field of (urban) criminology while having a completely different academic background (BA in International Relations). Moreover, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors at the Center for Security Studies (KEMEA) where I currently do my internship, Akis Karatrantos and Vasileios Theofilopoulos, for helping me to communicate with the relevant authorities and organizations in order to conduct the interviews that I wanted and also for their general comments on my questionnaires that I finally sent to those authorities. I would also like to thank my friends Christos and Dimitris, for their invaluable help during the field research and their assistance in taking photos of the areas. Finally, I would like to wholeheartedly thank my parents and my friend Sophia, for listening patiently to my concerns and for their general support during all this time. 1 Table of contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 2. Theoretical framework: Social disorganization theory in context ...................... 7 2.1 The discourse about the causes of crime ......................................................... -

Departures from Acropolis to Piraeus

1 AKTI MIAOULI 08.20 08.50 09.20 09.50 10.25 11.00 11.35 12.10 12.45 13.20 13.55 14.30 15.05 15.40 16.15 16.50 17.25 18.00 20.20 2 LION’S GATE 08.22 08.52 09.22 09.52 10.27 11.02 11.37 12.12 12.47 13.22 13.57 14.32 15.07 15.42 16.17 16.52 17.27 18.02 20.22 3 THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL TELSTELS 08.32 09.02 09.32 10.02 10.37 11.12 11.47 12.22 12.57 13.32 14.07 14.42 15.17 15.52 16.27 17.02 17.37 18.12 20.32 LULXUUXRUYRY THREETHREESTARSSTARS TELS TELS MUSEUM OF PIRAEUS LUXURYLUXURY 1 1AthenaeumAthenaeumInterInCterontinental,Continental,T 210T 21092069206000,000C7 , C7 25 A2chillion,5 Achillion,T 210T5225210 5225618, D618,2 D2 2 2DivaniDivaniPalacePalaceAcropoliAcropolis, T s210, T 21092809280100,100,D6 D6 26 A2chillea6 Achilleas, T 210s, T3233210 3233197, E197,4 E4 1 Metropolitan,1 Metropolitan,T 210 4112T 552100 4112 550 4 MIKROLIMANO HARBOUR 08.38 09.08 09.38 10.08 10.43 11.18 11.53 12.28 13.03 13.38 14.13 14.48 15.23 15.58 16.33 17.08 17.43 18.18 20.38 3 3ElecEletractraPalaPcalae, Tce210, T 21033703370000,000,E4 E4 27 A2c7ropolisAcropolis T 210T9249210 050-19249 050-1, D6 , D6 2 Piraeus2 ThePiroaeusxenia,TheT 210oxenia,4112T552100 4112 550 28 28 4 4EridanuEridanus, Ts210, T 21052055205360,360,C3 C3 AcropolisAcropolisSelecSelet, T 210ct, T9211210 9211610, D6106 , D6 THREE STHREETARS STARS 29 A2d9rian,Adrian,T 210T3221210 3221553, D553,4 D4 5 5GrandeGrandeBretagnBretagne, Te210, T 21033303330000,000,E4 E4 3 Cavo3D’orCavo, To210D’o4113ro, T 210744-41135 744-5 5 THE PLANETARIUM 08.46 09.16 09.46 10.16 10.51 11.26 12.01 12.36 13.11 13.46 14.21 14.56 -

Athens Constituted the Cradle of Western Civilisation

GREECE thens, having been inhabited since the Neolithic age, is considered Europe’s historical capital. During its long, Aeverlasting and fascinating history the city reached its zenith in the 5th century B.C (the “Golden Age of Pericles”), when its values and civilisation acquired a universal significance and glory. Political thought, theatre, the arts, philosophy, science, architecture, among other forms of intellectual thought, reached an epic acme, in a period of intellectual consummation unique in world history. Therefore, Athens constituted the cradle of western civilisation. A host of Greek words and ideas, such as democracy, harmony, music, mathematics, art, gastronomy, architecture, logic, Eros, eu- phoria and many others, enriched a multitude of lan- guages, and inspired civilisations. Over the years, a multitude of conque - rors occupied the city and erected splendid monuments of great signifi- cance, thus creating a rare historical palimpsest. Driven by the echo of its classical past, in 1834 the city became the capital of the modern Greek state. During the two centuries that elapsed however, it developed into an attractive, modern metropolis with unrivalled charm and great interest. Today, it offers visitors a unique experience. A “journey” in its 6,000-year history, including the chance to see renowned monu- ments and masterpieces of art of the antiquity and the Middle Ages, and the architectural heritage of the 19th and 20th cen- turies. You get an uplifting, embracing feeling in the brilliant light of the attic sky, surveying the charming landscape in the environs of the city (the indented coastline, beaches and mountains), and enjoying the modern infrastructure of the city and unique verve of the Athenians. -

A Rticles the First Marathon Races

Articles The First Marathon Races 1st International Olympic Games 1896 Stavros Tsonias & Athanasios Anastasiou here is hardly any book or monograph on the his- Marathon race, came to light as a result of the Athens T tory “Olympic Games” which does not make some Olympic Games of 2004. In addition, contemporary tech- reference to the first Marathon Race. Nowadays, for the nology which digitised the printed press of the time made majority of people, it is associated with Spyros Louis, the it more accessible. winner of the first race in 1896, and with the current dis- tance of 42,195 metres. The press of the time covered the The beginning organization of the “First International Olympic Games of 1896” in detail and promoted the marathon race as a Michel Bréal, a French philhellene and intellectual sug- major national event. Although a great deal of different gested that a marathon race should be held to com- and conflicting information concerning the Marathon memorate the feat of the messenger from the battle of race has been recorded, certain points have been left Marathon and his idea gave the impetus for the establish- unclear, particularly with regard to the preparatory and ment of this new race.1 During the first meeting of the trial races which preceded the final Marathon race. Both Temporary Committee of the Olympic Games (12-24 these preparatory and trial races highlight the historical November 1894) when the programme of games was evolution of the Marathon and are an area which has not agreed, the Marathon was included among the sports received sufficient analysis. -

Acropolis and Parthenon Bus Stop

Table of Contents TOUR MAP 2 HOP ON - HOP OFF BUS STOPS 1. SYNTAGMA SQUARE 3 2. MELINA MERKOURI / PLAKA 4 3. NEW ACROPOLIS MUSEUM 5 4. ACROPOLIS & PARTHENON 6 5. TEMPLE OF ZEUS 7 6. NATIONAL GARDENS (1) 8 7. BENAKI & CYCLADIC MUSEUM 9 8. PANATHENAIC STADIUM 10 9. NATIONAL GARDENS (2) 11 10. NATIONAL LIBRARY 12 11. NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM 13 12. OMONIA SQUARE 14 13. KARAISKAKI SQUARE (HOTEL STANLEY) 15 14. MONASTIRAKI / THISSION 16 15. KOTZIA SQUARE 17 ATHENS MUSEUMS 1. THE NEW ACROPOLIS MUSEUM (Bus Stop 3) 5 2. THE NATIONAL ARCAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM (Bus Stop 11) 13 3. THE GOULANDRIS MUSEUM OF CYCLADIC & ANCIENT GREEK ART (Bus Stop 7) 9 4. THE NUMISMATIC MUSEUM (Bus Stop 10) 19 5. THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL COLLECTIONS IN THE METRO (Bus Stop 1) 3 6. THE NATIONAL HISTORICAL MUSEUM (Bus Stop 15) 20 7. THE BENAKI MUSEUM (Bus Stop 7) 9 8. THE BYZANTINE & CHRISTIAN MUSEUM (Bus Stop 7) 18 9. THE WAR MUSEUM (Bus Stop 7) 19 10. METRO MAP 21 Tour map 11 13 12 15 10 14 7 1 9 6 4 2 8 3 5 2 Syntagma Square Bus Stop (Line 2 & 3-Syntagma Metro Station) 1 Visit the museum of the central Metro Station. It features a variety of historical items unearthed during the process of building the metro. Walk the Hermou Str., the commercial street of the district. With fashion shops and shopping centers promoting most international brands, it is in the top five most expensive shopping streets in Europe and the tenth most expensive retail street in the world. -

Athens • Attica Athens

FREE COPY ATHENS • ATTICA ATHENS MINISTRY OF TOURISM GREEK NATIONAL TOURISM ORGANISATION www.visitgreece.gr ATHENS • ATTICA ATHENS • ATTICA CONTENTS Introduction 4 Tour of Athens, stage 1: Antiquities in Athens 6 Tour of Athens, stage 2: Byzantine Monuments in Athens 20 Tour of Athens, stage 3: Ottoman Monuments in Athens 24 The Architecture of Modern Athens 26 Tour of Athens, stage 4: Historic Centre (1) 28 Tour of Athens, stage 5: Historic Centre (2) 37 Tour of Athens, stage 6: Historic Centre (3) 41 Tour of Athens, stage 7: Kolonaki, the Rigillis area, Metz 44 Tour of Athens, stage 8: From Lycabettus Hill to Strefi Hill 52 Tour of Athens, stage 9: 3 From Syntagma sq. to Omonia sq. 56 Tour of Athens, stage 10: From Omonia sq. to Kypseli 62 Tour of Athens, stage 11: Historical walk 66 Suburbs 72 Museums 75 Day Trips in Attica 88 Shopping in Athens 109 Fun-time for kids 111 Night Life 113 Greek Cuisine and Wine 114 Information 118 Michalis Panayotakis, 6,5 years old. The artwork on the cover is courtesy of the Museum of Greek Children’s Art. Maps 128 ATTICA • ATHENS Athens, having been inhabited since the Neolithic age, Driven by the echo of its classical past, in 1834 the is considered Europe’s historical capital and one of the city became the capital of the modern Greek state. world’s emblematic cities. During its long, everlasting During the two centuries that elapsed however, it and fascinating history the city reached its zenith in the developed into an attractive, modern metropolis with 5th century B.C (the “Golden Age of Pericles”), when its unrivalled charm and great interest. -

Cac Accr Cac Accr

Abstract Book EMERGENCY! PREPARINGEMERGENCY! for DISASTERS and CONFRONTINGPREPARING for the DISASTERS UNEXPECTED and CONFRONTINGin CONSERVATION the UNEXPECTED JOINT 44th ANNUALin CONSERVATION MEETING & 42nd ANNUAL CONFERENCE May 13-17, 2016 JOINT 44th ANNUALMontreal, MEETING Canada |& Palais 42nd desANNUAL Congrès CONFERENCE May 13-17, 2016 Montreal, Canada | Palais des Congrès CAC ACCRCAC ACCR Canadian Association for Conservation of Cultural Property EMERGENCY! Bruker’s art conservation solutions: Handheld XRF FTIR Micro-XRF Perfectly suited to analyze artifacts, help to restore objects without destroying PREPARING for DISASTERS and their original substance and determine the composition of materials. CONFRONTING the UNEXPECTED in CONSERVATION JOINT 44th ANNUAL MEETING & 42nd ANNUAL CONFERENCE May 13-17, 2016 Tracer handheld XRF Montreal, Canada | Palais des Congrès ALPHA FTIR Spectrometer LUMOS FTIR Microscope M6 JETSTREAM Micro-XRF Tracer series handheld XRF Non-destructive elemental analysis Vacuum or gas flow for measurements down to Ne LUMOS FTIR Microscope Best performing stand-alone FTIR microscope on the market Motorized ATR crystal with easy-to-use interface ALPHA FTIR Spectrometer Compact, easy-to-use; yet powerful for most applications Full range of QuickSnap FTIR accessories M6 JETSTREAM Micro-XRF Non-destructive elemental analysis of large objects Scanning areas of 800 mm x 600 mm with a variable spot size down to 100 µm Contact us for more details: www.bruker.com/aic [email protected] Conservation Innovation with Integrity -

Athens, Greece Overview

Courtesy of: Melody Moser Journeys Near and Far, LLC Athens, Greece Overview Introduction Sights in ancient Greece, and especially Athens, take on a larger importance than in most other places in the world. They are histories of democracy, Western civilization and philosophy firsthand. You can't help but walk around the Parthenon and the rest of the Acropolis and dream about the great ones who have come before you and whose footsteps you're in. Athens is a must-see on any European tour. The ancient and modern merge in this city in ways that are fascinating and sometimes overwhelming. Pollution wreathes the golden stones of the Acropolis and obscures views of the Saronic Gulf. Cars bleat and belch among ranks of concrete high-rises. But then you turn down a cobbled lane and discover vine-swathed tavernas, tortoises trundling through ancient ruins, and bazaars teeming with dusty treasures. Or The Parthenon is one of the most visited sights in Athens. perhaps you will encounter a sleek cafe, art gallery or an outdoor cinema that serves ouzo under the stars. Greece's capital has been reinventing itself; the results could not be more charming. The metro routes are extensive, and the stations dazzle with marble and antiquities. Congested downtown streets have been turned into pedestrian walkways, greatly reducing Athens' notorious smog and noise. Hotels, museums and archaeological sites have been revamped. Gentrified districts—such as Gazi—host cafes, clubs and chic restaurants, which even boast smokefree sections. Athens' 19thcentury Acropolis Museum has been replaced by a fine new Acropolis Museum that has brought 21st-century, high-tech architecture to the city in the form of a stunning exhibition space.