MIKE NOCK CONFOUNDS OZ JAZZ's KNOCKERS by John Clare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

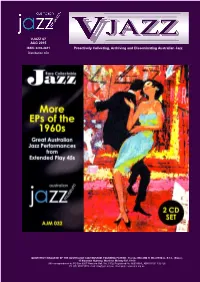

VJAZZ 67 AUG 2015 Proactively Collecting, Archiving and Disseminating Australian Jazz

VJAZZ 67 AUG 2015 ISSN: 2203-4811 Proactively Collecting, Archiving and Disseminating Australian Jazz Distribution 650 QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF THE AUSTRALIAN JAZZ MUSEUM. FOUNDING PATRON: The late WILLIAM H. MILLER M.A., B.C.L. (Oxon.) 15 Mountain Highway, Wantirna Melway Ref. 63 C8 (All correspondence to: PO Box 6007 Wantirna Mall, Vic. 3152) Registered No: A0033964L ABN 53 531 132 426 Ph (03) 9800 5535 email: [email protected]. Web page: www.ajm.org.au VJAZZ 67 Page 2 Letters to the Editor Contents 02 Letters to the Editor Dear Editor, 03 He’s the Drummer Man in the Band I am really overwhelmed about both articles, (Vjazz 66) the layout of it and how By Bill Brown you appreciate Coco Schumann. He will be very happy to read that he is not for- 04 The Museum’s 100-year-old Recordings gotten Down Under. As soon as I have the printed version I will forward it to him. I By Ken Simpson-Bull didn't know that you will use the photo with us, so I was flabbergasted to see this 06 Research Review - A Searing Sound young couple with Coco on p.7 :-) By John Kennedy OAM Well done, you did a great job, Ralph. 07 News from the Collection Jazzily By Ralph Powell Detlef 08 Visitors to the Archive 10 Instrument of Choice Dear Editor Oh So Beautiful Your members might be interested to know that Jack O’Hagan’s story and music 11 Two Studies in Brown is being brought back into focus. By Bill Brown I am near to completion of my grandfather Jack O’Hagan’s biography. -

MOONTRANE PROVIDES SOME JAZZ ACTION by Eric Myers Jazz Action S

MOONTRANE PROVIDES SOME JAZZ ACTION by Eric Myers ______________________________________________________________ Jazz Action Society concert February 6, 1980, Musicians’ Club Encore Magazine, March, 1980 ______________________________________________________________ his concert was opened by two sets provided by the John Leslie Trio, including the leader on vibraharp, Gary Norman (electric guitar) and T Richard Ochalski (acoustic bass). Their music consisted of jazz and popular music standards in swinging 4/4 tempo: Jerome Kern's All The Things You Are, Horace Silver's Opus de Funk and Doodlin', Oliver Nelson's Stolen Moments, Clifford Brown's Joy Spring etc. Richard Ochalski, bassist with the John Leslie Trio… These sets were mainly distinguished by the fluent playing of Gary Norman, who appears to be an impressive new addition to the ranks of Sydney jazz guitarists. He swings easily, and employs a nice vibrato at the end of his long notes, enabling the guitar to sing, in a style not unlike that of the American guitarist Larry Carlton. There was a hint of unease in John Leslie's playing, which appeared a little hurried and up on the beat, although this tendency was less apparent by the closing stages of the trio's second set. Inevitable sameness: The music played by this group suffered from an inevitable sameness, as the format adopted for each tune was, if I remember correctly, exactly the same: statement of theme, a solo from each player, then return to the theme. Bass solos are a welcome contrast, but in every tune? Without a drummer to provide some rhythmic drive and a few extra colours, this group played a little too long, which meant that Bob Bertles' Moontrane 1 was not able to start until 10.30pm. -

Introduction

Introduction In January 1997, two Sydney Morning Herald journalists produced a brief account of what they perceived to be the most important rock and roll sites in Sydney.1 Their sense of the city's rock histories extended to places of local mythology well beyond popular music's production and consumption: five star hotels as frantic sites of adoration of the Beatles ensconced within; psychiatric hospitals where career paths merged with psychosis; and migrant hostels as sites of cross-cultural ambitions. The article was a rare acknowledgement of the spaces and places of performersand fans' interaction. This thesis constitutes an extended response to the article's implicit desire to recognise alternative accounts of Australian popular music connected to broader city narratives. In analysing the rock music venues of Sydney as sites of interaction between musicians, fans and government, I am principally concerned with three interrelated themes: • The social construction of live performance venues from 1955 amidst the parallel construction of the performer and fan as an 'unruly' subject; • The industrial development of live performance: the live rock venue within commercial/economic structures; and • The dialectical tension of the above in reconciling the state's desire for manageable 'cultural citizens' with broader cultural policy (support for live rock and roll within arts policies). A more detailed explication of these strands is undertaken in Chapter One, in providing a theoretical overview of relations between popular culture and the state, and specific media/cultural/popular music studies approaches to cultural practice and policy. My personal interest in the histories of live rock venues parallels an increased 1 Jon Casimir and Bruce Elder, 'Beat streets - a guide to Sydney's rock and roll history', Sydney Morning Herald, 9th January, 1997, pp.29-30. -

Keith Stirling: an Introduction to His Life and Examination of His Music

KEITH STIRLING: AN INTRODUCTION TO HIS LIFE AND EXAMINATION OF HIS MUSIC Brook Ayrton A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of M.Mus. (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2011 1 I Brook Ayrton declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. Signed:…………………………………………………………………………… Date:………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Abstract This study introduces the life and examines the music of Australian jazz trumpeter Keith Stirling (1938-2003). The paper discusses the importance and position of Stirling in the jazz culture of Australian music, introducing key concepts that were influential not only to the development of Australian jazz but also in his life. Subsequently, a discussion of Stirling’s metaphoric tendencies provides an understanding of his philosophical perspectives toward improvisation as an art form. Thereafter, a discourse of the research methodology that was used and the resources that were collected throughout the study introduce a control group of transcriptions. These transcriptions provide an origin of phrases with which to discuss aspects of Stirling’s improvisational style. Instrumental approaches and harmonic concepts are then discussed and exemplified through the analysis of the transcribed phrases. Stirling’s instrumental techniques and harmonic concepts are examined by means of his own and student’s hand written notes and quotes from lesson recordings that took place in the early 1980s. 3 Acknowledgements Many thanks go to the following individuals for their thoughts and reflections on matters in the study and their remembrance of a time when Australian jazz music was prolific in the popular culture of this country. -

February Jazz Night

DOWN SOUTH JAZZ CLUB PRESENTS öCHASING CHET A JOURNEY\ THROUGH THE STYLE & SONGS OF THE LATE GREAT CHET BAKER FEATURING BEN MARSTON (TRUMPET) LACHLAN COVENTRY (GUITAR) JAMES LUKE (BASS) WHERE & WHEN AT CLUB SAPPHIRE THURSDAY 18th FEBRUARY 0 1 $15 JA$$ CLUB MEMBERS, $ 0 VISITORS MUSIC STARTS AT 7.30 PM Bookings ma1 be made with Kevin7Aileen on 64959853, at [email protected], or at door on the night (Clu2 2istro opens at 5.30 pm) On Thursday 18th February, at Club Sapphire, the Down South Jazz Club has great pleasure in presenting "Chasing Chet", with a journey through the style and songs of the late Chet Baker. The music of Chet Baker has always fascinated audiences. At the heart of his playing there was a fragile lyricism that was somehow sophisticated, yet raw and untrained. His performances often teetered on a knife edge and coupled with his unpredictable personal life it is easy to understand this fascination. Now we have the chance to experience a taste of this music as three of Canberra's finest musicians combine to examine the music of his later career. In the format of a drum-less trio, a combination often used by Baker, trumpeter Ben Marston, guitarist Lachlan Coventry, and bassist James Luke re-imagine some of the great standards of the twentieth century. With references to Chet Baker, Doug Raney, Niels-Henning and Ørsted Pedersen, the trio provide a clear vision of lyrical melodies, rich harmonic colourings and occasional virtuosic punctuation. Timeless music treated in a respectful yet contemporary way Born in Canberra, Ben began playing the trumpet at age 9, playing in the primary school band. -

NATIONAL JAZZ CO-ORDINATION NEWSLETTER No 7, September 26, 1988 Writer, Editor: Eric Myers ______1

NATIONAL JAZZ CO-ORDINATION NEWSLETTER No 7, September 26, 1988 Writer, Editor: Eric Myers ________________________________________________________ 1. International Students Big Band Festival, Bombay, 1991 This was referred to in my last newsletter, No 6, September 5, 1988. The Director of this festival, Niranjan Jhaveri, has written to suggest criteria for selection of the Australian group. Those suggestions are as follows: (a) Ability of the band to swing; (b) Arrangements that inspire the soloists; (c) Good soloists; (d) Unison and precision in the sections; (e) Original compositions. While mentioning Niranjan Jhaveri, he has written an article in the Irish jazz magazine Jazz News, July/August, 1988, in which he makes certain comments on Australian jazz. He refers to two concerts which Jazz India organised in Bombay for two overseas artists: the American trumpeter Eddie Henderson, and Marie Wilson, whom he refers to as "a truly marvellous Australian jazz vocalist". Marie, who was born in India, was passing through Bombay on her way to London and New York, and made a strong impact in her birth-place. Singer Marie Wilson, who was born in India: described by Niranjan Jhaveri as "a truly marvellous Australian jazz vocalist"… PHOTO CREDIT PETER SINCLAIR 1 Mr Jhaveri goes on to write: "Bombay is strategically placed and Jazz-India has the organisational capability to attract stop-overs for jazz groups travelling in either direction. We have had a string of Australian top echelon groups here already (Bob Barnard, Crossfire, The Benders, Galapagos Duck, Judy Bailey) thanks also to the financial support from the Australian establishment and this year we expect the Wizards of Oz (who are touring Europe this summer - North Sea, Montreux, Ronnie Scott's, etc) with saxophonist Dale Barlow and the remarkable bassist Lloyd Swanton, and later on the Bernie McGann Quartet. -

Jazz As Sinful Music

VJAZZ 40 Oct/Nov 2008 2008 BOARD of MANAGEMENT “Saving and Preserving our Australian Jazz for the Future” President: Bill Ford Vice President: From the General Manager Barry Mitchell see we are almost at the end of another year - with our AGM for 2008 just around the corner. General Manager: How time flies! I invite as many as possible to be at the AGM and the BYO BBQ lunch on Sun- Ray Sutton I th day, 9 November 2008. Collections Manager: Since our last communiqué, we have successfully acquitted the three Knox City Council grant pro- Mel Blachford jects for 2008. We also applied to KCC for funding covering another three projects for 2009, includ- Secretary: ing a computer software library management system (to cater for our large book library and our print- Gretel James ed material collection), and an upgrade to some of the equipment in the Sound Room. We’ve now Treasurer: been officially advised that unfortunately in this instance we were not successful. Lee Treanor The Fitzgibbon Dynasty exhibition (ending on 31st October) will be followed by an exhibition honour- Committee Members: ing the New Melbourne Jazz Band. Its leader, Ross Anderson, lives in Wantirna, and is a great sup- Jeff Blades porter of the VJA. Alan Clark Euan McGillivray of Museums Australia (Vic) has conducted a training session (for 15 volunteers) on Margaret Harvey conservation of photographs and prints, and two general sessions (for 25 volunteers) on the princi- Dr Ray Marginson AM ples of conservation and preservation. These sessions were extremely valuable in providing at- Marina Pollard tendees with basic concepts of conservation and preservation practices in relation to Museum Ac- Newsletter: creditation requirements. -

BOB BERTLES QUINTET PREVIEW by John Shand* ______

BOB BERTLES QUINTET PREVIEW by John Shand* __________________________________________________________ [This article appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald on November 11, 2005, and can be read at this link https://www.smh.com.au/news/cd--gig-reviews/bob- bertles-quintet/2005/11/11/1131578208022.html.] After 50 years in the business, jazz legend Bob Bertles is a master of re-invention… o optimism and enthusiasm promote a successful career, or does a successful career beget these qualities? The question leaps to mind when listening to or D chatting with the ebullient Bob Bertles. He is part of the musical folklore of Australia, and probably New Zealand and Britain as well. His saxophones have been heard with Johnny O'Keefe, Max Merritt and the Meteors, Nucleus, the Col Nolan Quartet, Ten Part Invention and his own quintet. It is a career that turns 50 next year and Bertles loves playing as much as ever, even if performance opportunities are sparser these days. ______________________________________________________ *John Shand is a playwright, librettist, author, journalist, drummer and critic. He has written about music (and occasionally theatre) for The Sydney Morning Herald for over 24 years. His books include Don’t Shoot The Best Boy!: The Film Crew At Work (Currency), Jazz: The Australian Accent (UNSW Press) and The Phantom Of The Soap Opera (Wizard). His website is www.johnshand.com.au. 1 "I don't mind the slow pace of it," he says. "The beauty of the position now is that I only do gigs that I really want to do. A lot of the work in the '70s, '80s and '90s was three or four nights in a club, and I couldn't stand doing that again. -

Stax of Sax Flyer

present ……… Stax of Sax ii Monday evening 4th July One of the biggest nights of saxophone ever seen in this country (just like a repeat of the hugely successful Manchester Lane - Stax of Sax 1996) Monday 4th July at LIMERICK ARMS Corner of Park St and Clarendon St, South Melbourne (only a few minutes away from the Festival Venues) Show starts at 7.30pm Dinner available from 6pm (or come for drinks straight after the festival finishes on Monday) A great place to chat with your peers and friends or just soak up the music and unwind The Limerick has a fantastic contemporary menu plus traditional pub meals. All at very reasonable prices. Bringing together well loved performers from the jazz, rhythm & blues, rock and roots scenes. ( more artists to be confirmed soon ) • Rob Glaesemann • Paul Williamson • Phil Bywater • Bob Bertles (Sydney) • Dean Hilson • Jeremy Diffey • Andrew Jackson • Christophe Genoux ... plus a hand picked rhythm section for a night to remember! – do not miss this event! Press Release September 2006 Stax of Sax – Manchester Lane 6th September 2006 What a night of saxophone! A full house at Manchester Lane were treated to a feast of Sax playing incorporating some of Melbourneʼs hottest up and coming players and seasoned professionals. Matt Amyʼs Really Big Band opened the evening with a bang and featured Savannah Blount, Tori Pearce, Lachlan Davidson, Cara Taber, David George and Jeremy Diffey. I spoke to a number of people who commented on how tight the section was, and the energy of the young group. If this is the next wave of Melbourneʼs talent, the scene is certainly in good hands. -

Ten Part Booklet

983 4640 TEN PART INVENTION Live at Wangaratta 31 OCTOBER 1999 THE MUSIC OF ROGER FRAMPTON 02 03 1 Jazznost 8’15 solos Roger Frampton piano, Warwick Alder trumpet, Bernie McGann alto saxophone 2 Randomesque 8’38 solos Roger Frampton piano, Miroslav Bukovsky flugelhorn, Sandy Evans tenor saxophone 3 The Dramatic Balladeer 8’26 solo James Greening trombone 4 Sorry My English 7’18 solos Roger Frampton sopranino saxophone, Bob Bertles baritone saxophone 5 Separate Reality 17’04 solos Ken James tenor saxophone, Bernie McGann alto saxophone, Warwick Alder trumpet, Roger Frampton piano Total Playing Time 49’55 All compositions by Roger Frampton Recorded live at the Wangaratta Festival of Jazz on 31 October 1999 JOHN POCHÉE (left) with ROGER FRAMPTON 04 05 TEN PART INVENTION I AM MORE THRILLED about the release of this CD, Ten Part Invention Live at Wangaratta, than any I have ever been associated with. John Pochée drums / leader Roger Frampton piano / sopranino saxophone There must be hundreds of special performances over my many years of broadcasting and Steve Elphick double bass listening to music that have left an impression on me, but then there are a few which are so Miroslav Bukovsky trumpet / flugelhorn special that they never leave me. Of all the many concerts that I have been fortunate to Warwick Alder trumpet experience, none has left such lasting memory as the performance we have on this CD – James Greening trombone Ten Part Invention at the Wangaratta Festival of Jazz on 31st October, 1999. Bernie McGann alto saxophone Ten Part Invention has been the most exciting and innovative large ensemble in Australia, Sandy Evans tenor saxophone since drummer and leader John Pochée created the band as a special medium for Australian Ken James tenor and soprano saxophones composers and improvisers, initially for concerts at the 1986 Adelaide Festival of Arts. -

NATIONAL JAZZ CO-ORDINATION NEWSLETTER No 5, May 30, 1988 Writer & Editor: Eric Myers, National Jazz Co-Ordinator ___

NATIONAL JAZZ CO-ORDINATION NEWSLETTER No 5, May 30, 1988 Writer & editor: Eric Myers, National Jazz Co-ordinator ________________________________________________________ 1. Stop Press: Death of Ricky May Sadly, I record the death of Ricky May, who died suddenly of a massive heart attack at the Regent Hotel, Sydney, in the early hours of June 1, 1988, shortly after receiving a standing ovation from a capacity audience at the Don Burrows Supper Club. He was 44 years old. Ricky May: a much-loved figure in the entertainment industry…PHOTO CREDIT EDMOND THOMMEN Ricky was a much-loved figure in the entertainment industry, and everyone will have his or her own favourite Ricky May story. On this sad occasion, let me merely quote from a review I wrote in The Australian on November 7, 1986, on the occasion of another Ricky May opening night at the Supper Club: "His opening performance at the Don Burrows Supper Club was vintage Ricky May: as always, a mixture of inspired chaos and great music... [He] is intrinsically a great jazz singer, but this is a season of cabaret rather than jazz. However, May takes the 1 listener quickly and easily into the frame of mind where one feels the pulse of the music. It is a precious ability. "Add his razor-sharp wit, an enormous capacity to send himself up as well as the audience, and his unquestioned ability to produce great music, and you have a compulsive mixture. It's one of the best entertainments in town." Ricky May (in white jacket) & Friends, L-R, Steve Murphy (guitar), David Glyde (sax), Col Loughnan (sax), Keith Stirling (trumpet), Herbie Cannon (trombone)…PHOTO CREDIT EDMOND THOMMEN I know that many people will wish to send their condolences to Ricky's wife Colleen, and their daughter Shani. -

MIKE NOCK CONFOUNDS OZ JAZZ's KNOCKERS by John Clare

MIKE NOCK CONFOUNDS OZ JAZZ’S KNOCKERS by John Clare* _______________________________________________________ [This piece first appeared in Nation Review, 20-26 April, 1978.] xcessively old readers who hung around the El Rocco at Kings Cross will remember Mike Nock, the small and rather goblin-shaped New Zealand E pianist who played as though his bum was on fire. He had a big influence on Australian jazz (so many of our best jazz and rock players actually came from New Zealand). He helped re-establish a hot attack more in keeping with the place than the cooler sounds that had been briefly fashionable. The Three Out Trio circa 1960: Mike Nock (piano) with Freddie Logan (bass) and Chris Karan (drums)…. _______________________________________________________________________________ *John Clare has written on diverse topics for most major Australian publications. He has published four books: Bodgie Dada: Australian Jazz Since 1945; Low Rent; Why Wangaratta?: Ten Years Of The Wangaratta Festival of Jazz; and Take Me Higher. His website is at http://johnclare.extempore.com.au/ 1 Yet he was best known for his work with a band whose name is so redolent of Downbeat magazine, Peter Gunn and post Kerouac ivy league hipness that I am embarrassed to type it. Okay, it was called the Three Out Trio. These silly names, this association of jazz with private eye shows and with businessmen and college boys going a bit far out during a night on the town present as easy a target for jazz haters as the more commercially packaged rock bands do for those who would see rock music as nothing more than the most forthright celebration of capitalism since the roaring 20s.