Old Mill, Aldermaston – History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

NEWSLETTER September 2017, Issue 7

NEWSLETTER September 2017, issue 7 Parish Council matters The Parish Council welcomes a new councillor, Sarah Sinclair, who has been co-opted following the resignation of Bernard Nix a few months ago. Sarah brings a new perspective to the Parish Council being the parent of school-aged children. There is an increasing number of young families in Purley on Thames, so it is important that they ‘have a voice’ on the council. We are really pleased Sarah is joining us. If you would like to find out more about what the Parish Council does and how it works you can speak to the Parish Clerk, to me or any of the other councillors or come as an observer to a parish meeting. The Parish Office sometimes receives information from local residents about speeding issues in Purley on Thames. When there are concerns about speeding the local community needs to collect speeding data then, when we have a picture of a problem in a particular area we can refer it to the Traffic and Road Safety Team at West Berkshire Council. To be effective at tackling excessive speed in this way, we need a team of Speed Indicating Device (SID) volunteers to gather the data. West Berkshire Council provides training for using the equipment and all volunteers must attend. We currently have three Parish Councillors trained with SID but you don’t need to be a councillor to do this and Purley needs at least six qualified people. The next SID training session is on 25th October 6.30-8.30pm in Newbury. -

260 FAR BERKSHIRE. [KELLY's Farmers-Continued

260 FAR BERKSHIRE. [KELLY'S FARMERs-continued. Bennett William, Head's farm, Cheddle- Brown C. Curridge, Chieveley,Newbury Adams Charles William, Red house, worth, Wantage Brown Francis P. Compton, Newbury Cumnor (Oxford) Benning Hy.Ashridge farm,Wokingh'm Brown John, Clapton farm, Kintbury, Adams George, PidnelI farm, Faringdon Benning- Mark, King's frm. Wokingham Hungerford Adams Richard, Grange farm, Shaw, Besley Lawrence,EastHendred,Wantage Brown John, Radley, Abingdon Newbury Betteridge Henry,EastHanney,Wantage Brown John, ""'est Lockinge, Wantage Adey George, Broad common, Broad Betteridge J.H.Hill fm.Steventon RS.O Brown Stephen, Great Fawley,Wantage Hinton, Twyford R.S.O Betteridge Richard Hopkins, Milton hill, Brown Wm.BroadHinton,TwyfordR.S.0 Adnams James, Cold Ash farm, Cold Milton, Steventon RS.O Brown W. Green fm.Compton, Newbury Ash, Newbury Betteridge Richard H. Steventon RS.O Buckeridge David, Inkpen, Hungerford Alden Robert Rhodes, Eastwick farm, Bettridge William, Place farm, Streat- Buckle Anthony, Lollingdon,CholseyS.O New Hinksey, Oxford ley, Reading Bucknell A.B. Middle fm. Ufton,Readng Alder Frederick, Childrey, Wantage Bew E. Middle farm, Eastbury,Swindon Budd Geo.Mousefield fm.Shaw,Newbury Aldridge Henry, De la Beche farm, Ald- Bew Henry, Eastbury, Swindon Bulkley Arthur, Canhurst farm, Knowl worth, Reading Billington F.W. Sweatman's fm.Cumnor hill, Twyford R.S.a Aldridge John, Shalbourn, Hungerford Binfield Thomas, Hinton farm, Broad Bullock George, Eaton, Abingdon Alexander Edward, Aldworth, Reading Hinton, -

35Th LLC 4 December 2003

AWE/MD/HCC/17-04/AB/LLC45mins Minutes of the 45th AWE Local Liaison Committee Meeting Thursday 8th June 2006 Present: Bill Haight Executive Chairman, AWE Chairman LLC Jonathan Brown Director Infrastructure, AWE Dr Andrew Jupp Director Assurance, AWE Alan Price Head Corporate Communications, AWE Avril Burdett Public Affairs Manager, AWE Secretary LLC Gareth Beard Head of Environment, AWE Cllr Mike Broad Tadley Town Council Cllr Malcolm Bryant Woking Unitary Authority Cllr Bill Cane Mortimer West End Parish Council Alan Craft Basingstoke & Deane Borough Council Cllr Margaret Dadswell Aldermaston Parish Council Cllr Maureen Eden Holybrook Parish Council Cllr Terry Faulkner Tadley Town Council Cllr John Heggadon Shinfield Parish Council Peter Hobbs Sulhamstead Parish Council Cllr Claire Hutchings Silchester Parish Council Cllr David Leeks Tadley Town Council Ian Lindsay Wasing Parish Meeting Cllr Royce Longton West Berkshire Council Cllr Jeff Moss Swallowfield Parish Council Cllr Irene Neill West Berkshire Council Cllr David Shirt Aldermaston Parish Council Cllr John Southall Purley-on-Thames Parish Council Cllr Alan Sumner Wokefield Parish Council Mr Bill Taylor Stratfield Mortimer Parish Council Cllr Tim Whitaker Mapledurham Parish Council Cllr David Wood Theale Parish Council Observers: Martin Sayers Nuclear Installations Inspectorate Darren Baker Environment Agency 1. Welcome and Apologies Apologies from: Cllr Peter Beard; Cllr Dennis Cowdery, Cllr Pat Garrett, Julie James, Cllr Michael Lochrie, Martin Maynard, Carolyn Murison, Tom Payne, Barry Richards, Cllr Murray Roberts and Cllr Graham Ward. The Chairman thanked Doug Mundy, one of the longest–standing LLC members who has now left Burghfield Parish Council and former Councillor David Dymond, representative of Reading Borough Council who has also left the LLC for their support on the LLC. -

Minutes of the 93Rd Atomic Weapons

OFFICIAL Minutes of the 93rd AWE Local Liaison Committee Meeting Wednesday 4th July 2018 AWE, Aldermaston Present: Haydn Clulow Director Site and Transformation AWE (Chair) Cllr Graham Bridgman West Berkshire Council Cllr Avril Burdett Tadley Town Council Cllr John Chapman Purley on Thames Parish Council Cllr Jonathan Chishick Tidmarsh with Sulham Parish Council Cllr Sophie Crawford Aldermaston Parish Cllr Debbie Fisher Wokefield Parish Council Cllr Roger Gardiner Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council Cllr David Leeks Tadley Town Council Cllr Clive Littlewood Holybrook Parish Council Cllr David Livingstone Silchester Parish Council Cllr Mollie Lock Stratfield Mortimer Parish Cllr Royce Longston Burghfield Parish Council Cllr George McGarvie Pamber Parish Council Cllr Ian Montgomery Shinfield Parish Council Jeff Moss Swallowfield Parish Council Cllr Ian Morrin West Berkshire Cllr Susan Mullan Tadley Town Council Amy Palmer West Berkshire Council Cllr Barrie Patman Wokingham Borough Council Cllr Jonathan Richards Basingstoke Council Carolyn Richardson West Berkshire Council Susie Tucker AWE Nick Bolton AWE Philippa Kent AWE John Steele AWE Gemma Wilson AWE Anna Markowska AWE Scott Davis-Hearn AWE Liz Pearce AWE Michele Maidment AWE Luke Joyner AWE Graduate Adam Karasinski AWE Graduate Regulators: Gary Cook Office for Nuclear Regulation Rob Greene Environment Agency Apologies Apologies had been received from Councillors Philip Bassil, Penee Chopping, Stuart Coker, Jan Gavin, Gerald Hale, John Miller, John Robertson, David Shirt, Richard Smith and Tim Whitaker 1 OFFICIAL Actions from previous meetings Action 2/90 John Steele to present on an updated AWE Travel Plan. We will be in a position to cover this at the next meeting, Action ongoing Approval of the 92nd Meeting minutes In respect to the minutes alluding to the planning status of Aldermaston Manor the amended wording adds accuracy. -

Purley Parish News

PURLEY PARISH NEWS JANUARY 2008 35 P For the Church & Community of PURLEY ON THAMES ST. MARY THE VIRGIN PURLEY ON THAMES www.stmaryspurley.org.uk RECTOR EDITOR Rev. Roger B. Howell Matt Slingsby The Rectory, 1 Westridge Avenue 24 Skerritt Way, Purley on Thames, 0118 941 7727 RG8 8DD [email protected] 0118 961 5585 [email protected] ORDAINED LOCAL MINISTER Rev. Andrew Mackie DISTRIBUTION 12 Church Mews Steve Corrigan 0118 941 7170 11 Mapledurham Drive Purley on Thames CURATE 0118 945 1895 Rev. Jean Rothery Oaklea, Tidmarsh Road, Tidmarsh SUBSCRIPTIONS 0118 984 3625 Les Jamieson 58a Wintringham Way CHURCHWARDENS Purley on Thames Mary Barrett 0118 941 2342 0118 984 2166 ADVERTISING Debbie Corrigan Liane Southam 0118 945 1895 1 Bakery Cottages, Reading Road, Burghfield Common, Reading CHURCH HALL BOOKINGS 0118 983 1165 (before 6pm please) Lorna Herring [email protected] 0118 942 1547 PRINTING BAPTISMS , WEDDINGS AND FUNERALS Richfield Graphics Ltd, Caversham All enquiries to the Rector If you are new to the area and would like to This magazine is published on the first Saturday of each subscribe to Purley Parish News, please contact month (except August). The price of each issue is 35p either Steve Corrigan or Les Jamieson. with a discounted annual subscription price of £3.50 for Comments and opinions expressed in this eleven issues. magazine do not necessarily reflect the views We welcome all contributions to this magazine, of the Editor or the PCC of St Mary's Church, particularly on local issues and events. Copy can be Purley on Thames – publishers of Purley Parish delivered either in writing or by email. -

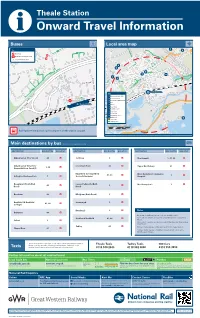

Theale Station I Onward Travel Information Buses Local Area Map

Theale Station i Onward Travel Information Buses Local area map IK Key C A Bus Stop B Rail replacement Bus Stop A Station Entrance/Exit 1 0 m in ut H es w a CF lk in g d LS is ta PO n BP c e TG L Theale Station Key BP Arlington Business Park C Calcot Sainsbury CF Cricket & Football Grounds IK Ikea Theale Station L Library LS Local Shops FG Football Ground PO Post Office SC Sailing Club TG Theale Green School H Village Hall SC Cycle routes Walking routes km 0 0.5 Rail replacement buses/coaches depart from the station car park. 0 Miles 0.25 Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at September 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP Aldermaston (The Street) 44 A Colthrop 1 A Thatcham ^ 1, 41, 44 A Aldermaston Wharf (for Crookham Park 44 A Upper Bucklebury 41 A 1, 44 A Kennet & Avon Canal) ^ Englefield (for Englefield West Berkshire Community 41, 44 A 1 A Arlington Business Park 1 B House & Gardens) Hospital Baughurst (Heath End Lower Padworth (Bath A 44 A 1 A Woolhampton [ 1 Road) Road) Beenham 44 A Midgham (Bath Road) 1 A Bradfield (& Bradfield Newbury ^ 1 A 41, 44 A College) Reading ^ 1 B Notes Brimpton 44 A Bus route 1 (Jet Black) operates a frequent daily service. Southend Bradfield 41, 44 A Bus route 41 operates one journey a day Mondays to Fridays from Calcot 1 B Theale. -

1 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

1 bus time schedule & line map 1 Newbury - Reading via Thatcham, Woolhampton, View In Website Mode Theale The 1 bus line (Newbury - Reading via Thatcham, Woolhampton, Theale) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Newbury: 5:05 AM - 8:30 PM (2) Reading Town Centre: 5:00 AM - 11:02 PM (3) Theale: 9:30 PM - 10:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 1 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 1 bus arriving. Direction: Newbury 1 bus Time Schedule 74 stops Newbury Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:20 AM - 6:45 PM Monday 5:05 AM - 8:30 PM Blagrave Street, Reading Town Centre Blagrave Street, Reading Tuesday 5:05 AM - 8:30 PM Friar Street, Reading Town Centre Wednesday 5:05 AM - 8:30 PM St Marys Butts, Reading Town Centre Thursday 5:05 AM - 8:30 PM St Mary's Butts, Reading Friday 5:05 AM - 8:30 PM Castle Street, Reading Town Centre Saturday 6:20 AM - 8:25 PM Castle Street, Reading Russell Street, Castle Hill - Bath Road Janson Court, Reading 1 bus Info Downshire Square, Castle Hill - Bath Road Direction: Newbury Bath Road, Reading Stops: 74 Trip Duration: 78 min Berkeley Avenue, Southcote Line Summary: Blagrave Street, Reading Town Centre, Friar Street, Reading Town Centre, St Marys Southcote Road, Southcote Butts, Reading Town Centre, Castle Street, Reading Bath Road, Reading Town Centre, Russell Street, Castle Hill - Bath Road, Downshire Square, Castle Hill - Bath Road, Berkeley Parkside Road, Prospect Park Avenue, Southcote, Southcote Road, Southcote, Parkside Road, Prospect Park, Liebenrood -

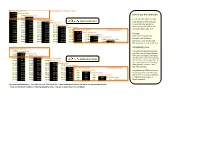

How to Use This Fare Chart Adult Single Fares Adult Return Fares

Newbury Bus Station simplyNewbury & Thatcham zone £1.90 Cromwell Road £2.20 £1.90 Henwick Lane How to use this fare chart £3.00 £2.20 £1.90 Colthrop Lane To use this fare chart find the £3.70 £3.50 £3.20 £1.90 Woolhampton adult single fares stop nearest to where you get £4.40 £4.00 £3.90 £3.20 £1.90 Beenham Turn on and the stop nearest to £4.40 £4.40 £4.20 £3.60 £3.20 £1.90 Wigmore Lane where you get off. Where the £4.40 £4.40 £4.20 £3.60 £3.20 £1.90 £1.90 Theale Schools two meet, that's your fare! £4.40 £4.40 £4.20 £3.60 £3.20 £1.90 £1.90 £1.90 The Crown at Theale simplyReading zone £5.00 £5.00 £5.00 £4.30 £4.00 £3.50 £3.00 £3.00 £1.30 Calcot Sainsbury's Example £5.00 £5.00 £5.00 £5.00 £4.20 £4.00 £3.00 £3.00 £2.00 £1.30 Calcot Mill Lane If you are travelling from £5.00 £5.00 £5.00 £5.00 £4.20 £4.00 £3.00 £3.00 £2.00 £1.30 £1.30 Greenwood Road Henwick Lane to Calcot £5.00 £5.00 £5.00 £5.00 £4.40 £4.00 £3.00 £3.00 £2.00 £2.00 £2.00 £2.00 Southcote Road Sainsbury's your adult single £5.00 £5.00 £5.00 £5.00 £4.40 £4.00 £3.00 £3.00 £2.00 £2.00 £2.00 £2.00 £1.30 Reading Station fare would be £5 (£6.50 return) simplyReading zone Newbury Bus Station £3.00 Cromwell Road The simplyReading zone boundary £3.50 £3.00 Henwick Lane is at The Crown at Theale. -

Local Cycling & Walking Infrastructure Plan

Local Cycling & Walking Infrastructure Plan LCWIP 1 Contents Foreword 3 1 Introduction 4 2 Integration with Active Travel Policy 7 3 Active Travel context 9 4 Network planning for cycling 14 5 Network planning for walking 24 6 Infrastructure improvements 26 7 Prioritisation, integration and next steps 30 Appendicies Appendix A Summary of Relevant Policy and Guidance 32 Appendix B Cycle Route Network Plans 36 Appendix C Eastern Area Cycle Routes 39 – Audit Key Findings and Recommended Improvements Appendix D Newbury and Thatcham Prioritised 42 Strategic Cycle Routes – Audit Key Findings and Recommended Improvements Appendix E Newbury and Thatcham 69 Key Walking Route Network Plan Appendix F Newbury and Thatcham Prioritised 70 Key Walking Routes – Audit Key Findings and Recommended Improvements 2 LCWIP Foreword West Berkshire Council is pleased to present our district. This joined-up approach covered our Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure cross-boundary routes and commuter zones on Plan (LCWIP) to act as a blueprint for future the urban fringe of Reading. We have adopted active travel routes in our district. It sets our a similar approach identifying walking and ambition to create a network of high-quality cycling routes in the settlements of Newbury interconnected cycle routes and walking zones and Thatcham and this report will prioritise the to encourage greater uptake of sustainable improvements of both urban areas together in travel modes. a comprehensive strategy for investment. By adopting the long-term approach provided The LCWIP has focused on identifying key by the LCWIP we can ensure that planning corridors connecting residential areas (both policy, public health, highway improvements, existing and proposed) to destinations such regeneration and developments are better as town centres, local centres, schools, linked to a coherent strategy that will employment sites and transport hubs. -

Hillside the Crescent Padworth Berkshire RG7 5QS Hillside the Crescent Padworth Berkshire RG7 5QS Price Guide: £460,000 Freehold

Hillside The Crescent Padworth Berkshire RG7 5QS Hillside The Crescent Padworth Berkshire RG7 5QS Price Guide: £460,000 Freehold A delightful extended semi detached family home with a garage and beautiful south west facing garden • Entrance hallway • Living room • Large fitted kitchen/dining room • 4 Bedrooms • Family bathroom • Garage • Driveway parking • Large rear garden • Double glazing • Oil fired central heating Location Padworth is 4 miles to the west of Junction 12 of the M4 at Theale and Reading and some 8 miles to the east of Newbury. It is a small village adjoining picturesque Aldermaston Wharf just to the south of the A4. It is ideally located for excellent communications being 7 miles west of Reading and the property is only a 10 minute walk from Aldermaston station. The surrounding countryside is particularly attractive and comprises Bucklebury Common and Chapel Row to the north (an area of outstanding natural beauty). The major towns of Reading and Newbury offer excellent local facilities. A lovely family home and garden ! Michael Simpson Description This lovely extended family home offers spacious and flexible accommodation arranged over two floors comprising an entrance hallway, cosy living room with open fire, a good size open plan fitted kitchen/dining room and cloakroom on the ground floor. On the first floor are four double bedrooms and the family bathroom. Other features include oil fired central heating and double glazing. Outside The front of the property is approached via the driveway which leads to the front door and garage. The rear garden has established flower bed borders offering a variety of lovely shrubs, plants and flowers. -

Autumn House, Birds Lane, Midgham, Reading, Berkshire Autumn House Room, Both of Which Have Chic, Contemporary Birds Lane, Suites

Autumn House, Birds Lane, Midgham, Reading, Berkshire Autumn House room, both of which have chic, contemporary Birds Lane, suites. Midgham, Outside To the front of the property there is an area of lawn Reading, Berkshire and a block-paved driveway, providing parking space for several vehicles. The garage provides RG7 5UL ample storage and workshop space, while timber gates open onto a paved and gravel area to the A beautifully presented 6 bedroom family home side of the house, which could be used for further with modern accommodation in a peaceful parking. The house benefits from solar panels. The village location garden to the rear has an area of paved terracing Midgham mainline station 1.8 miles (57 minutes immediately at the back of the house, a well- to London Paddington via Reading), Thatcham maintained lawn, a rockery and a further small area town centre 3.2 miles, Newbury town centre 6.0 of patio to the side, as well as established border miles, M4 (Jct 12) 7.8 miles hedgerow. Location Reception hall | Sitting room | Study/office The village of Midgham is set in a rural location Dining area | Kitchen | Utility | Cloakroom | 6 close to the popular Berkshire towns of Thatcham Bedrooms | Dressing room | Bathroom | Shower and Newbury. There is a local pub in Midgham, room | Garden | EPC rating C while the neighbouring village of Woolhampton has a local shop, a pub and a primary school, as well as The property the independent Elstree School. The nearby village Autumn House is a superb, detached home, which of Aldermaston Wharf provides further everyday has been extended and modernised to provide amenities, including local shops.