Clock Article Pp17-29

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ole Rømer's Pocket Watch

Poul Darnell Ole Rømer’s pocket watch Antiquarian Horology, Volume 36, No. 4 (December 2015), pp. 541–543 The AHS (Antiquarian Horological Society) is a charity and learned society formed in 1953. It exists to encourage the study of all matters relating to the art and history of time measurement, to foster and disseminate original research, and to encourage the preservation of examples of the horological and allied arts. To achieve its aims the AHS holds meetings and publishes books as well as its quarterly peer-reviewed journal Antiquarian Horology. The journal, printed to the highest standards with many colour pages, contains a variety of articles, the society’s programme, news, letters and high-quality advertising (both trade and private). A complete collection of the journals is an invaluable store of horological information, the articles covering diverse subjects including many makers from the famous to the obscure. The entire back catalogue of Antiquarian Horology, every single page published since 1953, is available on-line, fully searchable. It is accessible for AHS members only. For more information visit www.ahsoc.org Volume 36, No. 4 (December 2015) contains, apart from the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, AHS News, Letters to the Editor and Further Reading, the following articles and notes: NUMBER FOUR VOLUME THIRTY-SIX DECEMBER 2015 English provincial clockmaking 1695–1840. The role of the thirty-hour longcase clock – Part 2 by Michael Grange John & Miles Brockbank, their life and work by A.D. Stewart Short-time measurement – the contribution of German electrical horology by Thomas Schraven Ole Rømer’s pocket watch, by Poul Darnell The clocks of an Anglo-Welsh knight: Sir Edward Don (1482-1551), by William Linnard 1 DECEMBER 2015 Ole Rømer’s pocket watch Poul Darnell Ole Rømer’s letter to John Locke Fig. -

History of Escapement Mechanisms

Journal of Mechatronics, Automation and Identification Technology Vol. 3, No.2. pp. 8-12 History of Escapement Mechanisms Miša Stojićević, Branislav Popkonstantinović, Ljubomir Miladinović, Ivana Cvetković Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Belgrade, Serbia Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Belgrade, Serbia Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Belgrade, Serbia Innovation Centre of the Mechanical Faculty Belgrade, Serbia [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—This paper describes a history of development one of the most important part of mechanical clock – escapement mechanism. Escapement mechanism is a device designed to maintain a constant average speed of the escape wheel, by allowing it to rotate to the desired angle at certain impulse of time. While doing that it simultaneously support the oscillations of the pendulum or balance spring, by compensating for friction losses and air resistance. 7 century long history of escapement mechanisms, from 13th century verge mechanism up to modern-day escapements that can be found in luxury watches, will be shortly presented. Through lives of famous clockmakers and their achievements in field of making escapement mechanism will be given a new insight in science of time keeping - horology. Keywords— escapement, mechanism, history, watches, clock I. INTRODUCTION Fig. 1 Verge escapement The escapement mechanism is a key part of every However, the late middle Ages also recorded the mechanical clock, because it maintains and counts appearance of hand and pocket watchmakers. The first oscillations of the oscillator and thus measures the flow portable timer, the so-called. The Nuremberg egg (Fig. 2), of time. It can be also said that escapement is a device which could be worn in a pocket or purse (Ger.: that transfers energy to the timekeeping element (the taschenuhr), was constructed in Nuremberg by "impulse action") and allows the number of its watchmaker Peter Henlein, (1485-1542) oscillations to be counted (the "locking action"). -

London Women in Horology by Bob Frishman, FNAWCC (MA)

© 2020 National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Inc. Reproduction prohibited without written permission. London Women in Horology By Bob Frishman, FNAWCC (MA) he 2020 NAWCC Ward Francillon Time by Samuel Elliott Atkins, a former Clerk of the Company, Symposium, “Horology 1776,” will take place in and privately printed in 1881. Top of the roster is Mariane T Philadelphia on October 1–3 at the Museum of Viet who was “bound” for seven years on January 27, the American Revolution. One important speaker on 1715, to her father Claude. the conference theme of timekeeping during our War English women’s names also are among the tiny-print of Independence will be Emily Akkermans, curator at 873 pages of Watchmakers and Clockmakers of the London’s Greenwich Observatory. She is one of the World by Brian Loomes, published in 2006, although women featured in this article, and she will be happy to most were widows and daughters of men in the trade. On meet and chat with all who attend. Symposium details and page 352 for example, Mrs. Agnes Harrison of Morpeth is registration can be found at www.horology1776.com . listed in 1884 as “Widow of Francis Harrison.” Miss Viet Horology in England has always been dominated by men. appears here, too, on page 798, with the additional detail Names like Fromanteel, Harrison, Tompion, Graham, that her father had a partner, Thomas Mitchell. Mudge, Ferguson, Vulliamy, and now George Daniels In Colonial America and then in the United States the are on every list of the most famous practitioners, situation was similar, although we know that from the theoreticians, and scholars of our applied science. -

The Greenwich Clock at Towneley by Tony Kitto

The Greenwich Clock at Towneley by Tony Kitto Towneley Hall Art Gallery and Museums 2007 Copyright Burnley Borough Council Reading the time from the Greenwich Clock The hour hand goes round the dial once every twelve hours in the usual way but the minute and second hands take twice as long as is normal. It takes 2 hours for the minute hand to go round. At the top of the dial, starting at 12 o'clock, there are 60 divisions of one minute down to 6 o'clock and another 60 divisions back to 12 o'clock. The minutes are difficult to read because the minute hand shares the same dial as the hour hand. In comparison, it is relatively easy to read the second hand. The second hand goes round its own dial with 120 divisions, marked out in 10 second periods, once every 2 minutes. We expect a minute hand to go round the dial once an hour. Most people estimate the time from the angle of the minute hand but that is misleading when looking at this clock. 2:00 ? 2:15 ? 3:30 ? 3:45? 4:00? yes no, its 2:30 no, its 3:00 no, its 3:30 yes The Greenwich Clock at Towneley The Greenwich Clock in the entrance hall at Towneley is a reconstruction of one of a pair of clocks presented to the Royal Observatory at Greenwich by Sir Jonas Moore in 1676. It was made in 1999 by Alan Smith of Worsley, Greater Manchester, to show how the original clocks worked. -

FINE CLOCKS Wednesday 14 December 2016

FINE CLOCKS Wednesday 14 December 2016 FINE CLOCKS Wednesday 14 December at 2pm 101 New Bond Street, London VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES Sunday 11 December +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 James Stratton M.R.I.C.S Monday to Friday 11am to 3pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax + 44 (0) 20 7468 8364 8.30am to 6pm Monday 12 December To bid via the internet please [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 9am to 4.30pm visit bonhams.com Tuesday 13 December Charles Crisford As a courtesy to intending 9am to 4.30pm Please note that bids should be +44 (0) 20 7468 8371 bidders, Bonhams will provide a Wednesday 14 December submitted no later than 4pm on [email protected] written Indication of the physical 9am to 12pm the day prior to the sale. condition of lots in this sale if a New bidders must also provide Administrator request is received up to 24 SALE NUMBER proof of identity when submitting Magdalena Drafiova hours before the auction starts. 23554 bids. Failure to do this may result +44 (0) 20 7468 8204 This written Indication is issued in your bids not being processed. [email protected] subject to Clause 3 of the Notice CATALOGUE to Bidders. Bidding by telephone will only be £20.00 accepted on lots with a low Please see back of catalogue estimate in excess of £1,000 for important notice to bidders Live online bidding is ILLUSTRATIONS available for this sale Front cover: Lot 69 Please email [email protected] Back cover: Lot 23 with “Live bidding” in the subject Inside front cover: Lot 39 line 48 hours before the auction Inside back cover: Lot 63 to register for this service. -

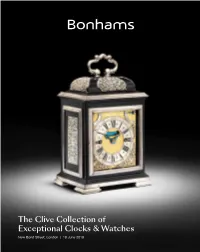

The Clive Collection of Exceptional Clocks & Watches

The Clive Collection of Exceptional Clocks & Watches New Bond Street, London | 19 June 2019 STUDIO OF WILLEM WISSING (Amsterdam 1656-1687 Burghley) Full-length portrait of Queen Mary II, a palace beyond. The Clive Collection of Exceptional Clocks & Watches New Bond Street, London | Wednesday 19 June 2019 at 3:30pm VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES Sunday 16 June, 11am to 3pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Clocks Monday to Friday Monday 17 June, 9am to 4.30pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax James Stratton M.R.I.C.S 8.30am to 6pm Tuesday 18 June, 9am to 4.30pm To bid via the internet please + 44 (0) 20 7468 8364 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Wednesday 19 June, 9am to 12pm visit bonhams.com [email protected] Richard Davis As a courtesy to intending The Clive Collection will Please note that bids should be + 44 (0) 20 7468 2371 bidders, Bonhams will provide follow the Fine Clocks submitted no later than 4pm on [email protected] a written indication of the sale, starting no earlier the day prior to the sale. physical condition of lots in this than 3.30pm New bidders must also provide Watches sale if a request is received up to proof of identity when submitting Jonathan Darracott 24 hours before the auction starts. bids. Failure to do this may result +44 (0) 20 7447 7412 This written indication is issued in your bids not being processed. [email protected] subject to Clause 3 of the Notice SALE NUMBER to Bidders. 25730 Administrator Lots 101-107 Vanessa Howson Live online bidding is + 44 (0) 20 7468 8204 Please see back of catalogue available for this sale [email protected] for important notice to bidders CATALOGUE Please email [email protected] Softback with “Live bidding” in the subject ILLUSTRATIONS £20.00 REGISTRATION line 48 hours before the auction IMPORTANT NOTICE Front cover: Lot 103 to register for this service. -

List of Memorials Monitored by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers

LIST OF MEMORIALS MONITORED BY THE WORSHIPFUL COMPANY OF CLOCKMAKERS Frederick J Barraud (1785–1859), Woodbury Park Cemetery, Tunbridge Wells TN4 9NH Follow path down into the cemetery taking the first left hand path. Continue left at the junction with three other paths and you will see Barraud shortly on the right hand side. Edward John Dent (1790–1853), Kensal Green Cemetery W10 4RA Frederick William Dent (1808–1860), Kensal Green Cemetery W10 4RA Thomas Earnshaw (1749–1829): Blue plaque, 120 High Holborn, London EC4Y 1HT. On the wall of the Cheltenham & Gloucester Building Society on the north side of High Holborn opposite Holborn tube station, and close to the pedestrian lights. Plaque at St Giles-in-the-Fields Church, 60 St Giles High Street, London WC2H. It is at the right-hand end of the vestibule when facing the altar, and it measures 19″ by 14″. It was placed there by the Clockmakers Company in 1929. John Ebsworth (1642–1699), St Margaret’s, Lothbury, London EC2R 2HH The stone covering Ebsworth’s tomb lies in the far north-east corner of the chancel of St Margaret's Lothbury. It is often covered up. Charles Frodsham (1810–1871), Highgate Cemetery N6 6PJ William James Frodsham (1778–1850), Highgate Cemetery N6 6PJ Rupert T Gould (1890–1948): Grave is at St Giles’ Church, Ashstead KT21 1EN in Surrey – best found by entering the churchyard through the small gated entrance off the approach to the main entrance to the church. Follow the path from this entrance to where it turns right and the grave is two to three graves along this right turn on the right. -

Last Updated January 15, 2013. Copyright 1995-2013 by Parnav

Last updated January 15, 2013. Copyright 1995-2013 by Parnav Singh & Michael P. Murray The following is a summarization of discussions which occurred on the E-mailing list (listserver) Clocks. To join in this and other horological discussions please join the mailing list Clocks or Clocksmiths. This list was compiled by Parnav Singh ([email protected]) and downloaded from the E-mailing list Clocks. Please see the file csignup.mcc for details on how to join this mailing list. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chronology of the Development of Watches -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1470 First spring driven watch 1470 Fusee introduced in Italy 1500 Spring-driven, drum-shaped table clock 1505 Peter Henlein makes the first watch 1510 Stackfreed introduced to control tension in the mainspring 1520 Brass used in France to make watches 1525 Jacob Zech introduces his fusee 1550 Screws used in metal 1575 Balance wheel is introduced 1600 First watches are produced in London 1610 Enamel cases come into vogue 1630 Watch glasses are first used 1635 Paul Viet uses enamel dials 1650 Round watch cocks are used 1658 Robert Hooke invents the "straight" balance spring 1665 Watch fusees made of chain instead of gut 1674 Christian Huygens invents the spiral balance spring 1676 Motion works and minute hand introduced by Daniel Quare 1680 Second hand introduced 1694 Nicholas Facio first uses jewels in watches -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Geometry-Based Simulation of Mechanical Movements and Virtual Library

Geometry-Based Simulation of Mechanical Movements and Virtual Library TAM, Lam Chi A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Automation and Computer-Aided Engineering © The Chinese University of Hong Kong August 2008 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or a whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. Ayvyai^A Thesis/ Assessment Committee Professor Hui,Kin Chuen (Chair) Professor Du, Ruxu (Thesis Supervisor) Professor Kong, Ching Tom (Thesis Co-supervisor) Professor Wang, Chang Ling Charlie (Committee Member) Professor Y. H. Chen (External Examiner) Abstract Abstract Mechanical timepiece is an intricate precision engineering device. Invented some four hundred years ago, mechanical timepieces, including watches and clocks, are fascinating gadgets that still attract millions of people around the world today. Though, few understand the working of these engineering marvels. This thesis presents a Virtual Library of Mechanical Timepieces. The Virtual Library is an online database containing different kinds of mechanisms used in mechanical watches / clocks. It uses 3-dimension (3D) Computer-Aided Design (CAD) models to demonstrate the working of these mechanisms. The Virtual Library provides an educational tool for various people who are interested to mechanical timepieces, including engineering students (university students and vocational school students), watchmakers, designers, and collectors. In addition, the CAD models are drawn to exact dimension. As a result, it can be used by watchmakers to validate their designs. -

The Old Clock Book

•v tjvt:*rntemmi 1 ;•••.•• •- •.= iW'.v I.v <• wm’mv frjTj> (-yj Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/b24854414 THE OLD CLOCK BOOK ( Et.i Tehhy's Fiust Ci.ock. Buii.t 1702 Owned by bis descendants and in soinjr order Frontispiece THE OLD CLOCK BOOK BY N. HUDSON MOORE AUTHOR OF “The Old China Book,” “The Old Furniture Book,” “Old Pewter, Brass, Copper and Sheffield Plate,” “The Old Lace Book,” Etc. WITH ONE HUNDRED AND FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS “ Time was, time is; time is past" LONDON WILLIAM HEINE MANN 1913 ; VI PREFACE Esq., of The Steam Turbine Works, Hartford, Conn. to Marshall G. Hill, Esq., Afton, N. Y. ; to Francis H. Bigelow, Esq., of Cambridge, Mass.; to Francis G. Atwater, Esq., of Meriden, Conn.; and to Maynard A. Dominick, Esq., through whose efforts permission was granted to copy the records of the London Clock- makers’ Company, to each and all I record my grateful thanks. Rochester, N. Y., July, 1911, 1 CONTENTS ENGLISH CLOCKS Early Timekeepers 3 Clock Collectors 9 Domestic Clocks 1 The Clockmakers’ Company—Pendulums—Frets 13 Bracket Clocks 19 Table Clocks and Early Watches 23 Early Watches 25 Watch Papers 34 Long-case Clocks 39 Tompian and Graham 45 Edward Barlow 49 John Harrison and Others 53 Scottish Makers 56 Curious Clocks and Watches 61 The Largest Clock in the World 76 AMERICAN CLOCKS American Clocks and Clockmakers 91 New England Clockmakers 100 The Terry Family 105 vii 1 1 * Viu CONTENTS AMERICAN CLOCKS—Continued Other Connecticut Clockmakers 122 Seth Thomas 122 Silas Hoadley . -

Horologica Review, November 2016

Horologica For more information on the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Inc., visit nawcc.org. Share reviews and announcements of new and interesting books, websites, digital media programs, periodicals, exhibits, and all else pertaining to horology. Send contributions to Editor Therese Umerlik at [email protected] or mail to NAWCC, Inc., Publications Department, 514 Poplar St., Columbia, PA 17512-2130. In-depth Look at One of England’s Leading Clockmakers of the Golden Age ost serious students of English timekeep- ing in the golden era of British horology will have heard of famous clockmakers, such as Thomas Tompion (1639-1713), MJoseph Knibb (1640-1711), George Graham (1673-1751), and John Harrison (1693-1776). But a handful of arti- sans who were their contemporaries made clocks of sim- ilar quality and were nearly as prominent at the time. Joseph Windmills (circa 1640-1724) and Christopher Pinchbeck (circa 1670-1732) come to mind. Biographies were published about them. But no biography had been written on another prominent example, Charles Gret- ton (1647-1731), despite a large sample of his surviving clock making and watchmaking. The book under review not only closes that gap, but it does so in a manner that is surprising in its thorough- ness and insightfulness. After more than a decade of hard work, NAWCC members Dennis and Laila Rad- age, of British Columbia, Canada, and fellow Gretton enthusiast Warner Meinen from Holland have created a book, an amazing monograph, that goes beyond the standard glossy biography of a master craftsman of yes- teryear. The book reflects the passion the three authors have developed for the life, the output, and the era of their subject. -

The Tom Scott COLLECTION Selling Exhibition – Part I

Carter Marsh Co. The Tom Scott COLLECTION Selling Exhibition – Part I Winchester 4th – 25th July 2015 Carter Marsh Co. FINE CLOCKS AND WATCHES The Tom Scott Collection Selling Exhibition – Part I Saturday 4th July to Saturday 25th July 2015 We are immensely privileged to be selling the most important collection of English clocks to come on the market in the UK since the Wetherfield collection in 1928. Early in his collecting career, the late Tom Scott recognised and appreciated the extraordinary horological contribution made by Thomas Tompion and his The late Tom Scott successor, George Graham. These clockmakers became Tom’s primary interest and his acquisitions included not only three Tompion full grande sonnerie clocks but also items by makers apprenticed or associated to these great masters; these clocks make up over half of his collection. Tom was not exclusive in his interest, and other premier makers such as Knibb and Quare are also well represented. Many of the important items need little introduction, as their significance is both recognised and well documented; these represent a once in a lifetime’s opportunity for collectors to acquire clocks of this gravity and significance. In testimony to Tom’s discerning and shrewd collecting ability, with guidance from Richard Garnier, even the more unassuming clocks in the collection are, almost invariably, interesting and unusual in their own right, so as well as the iconic pieces there are also many other desirable and beautiful horological examples, all priced at a very affordable and competitive level. There is very little duplication in the collection but, with over 100 items, we have split it into two selling exhibitions, both in our Winchester premises, with the second starting in November 2015.